With the conclusion of The Man in the High Castle‘s TV version, I’ve been having a few conversations about the ins and outs of turning the novel into a considerably bloated series. Or maybe I should say simply that when I realized at the end of the first season that, having made their choices and essentially filmed their version of the book, the producers were now going to go for further seasons, I was dismayed. Who would be making the choices now that the original author was not available, and how would the plot unfold? An ongoing series can do this well, of course — consider the absorbing tale unfolding in The Expanse — but going well outside the boundaries of a foundational novel can often be asking for trouble.

While I wasn’t much taken with the way The Man in the High Castle‘s plot played out on TV, I did go ahead and watch every episode because I found the visuals so entrancing. The idea of a Japanese occupied California was fully realized, with touches like the Japanese fascination with American pop culture and antiques, the use of the I Ching by the trade minister (Dick’s fascination with and use of the book in his plots is well documented), and the interactions between the Nazi government in America and the Japanese one, with glimpses of Concord-like airliners bearing swastikas, were compelling and compulsively watchable.

So this is a post about film visuals, and I’m thinking about the topic because another Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is suddenly back in the news thanks to the death of a key figure in the movie made from it, Bladerunner. This was Syd Mead, who worked on the 1982 classic directed by Ridley Scott (who also had a hand in Amazon’s take on The Man in the High Castle). Mead served as a concept designer on the movie, a role he had also played in Hollywood creations like Aliens, Star Trek: The Movie and Tron. Here, as with The Man in the High Castle, I am drawn into concept as expressed in breathtaking design, for both film and TV series presented visual delights (although Mead was not involved with High Castle).

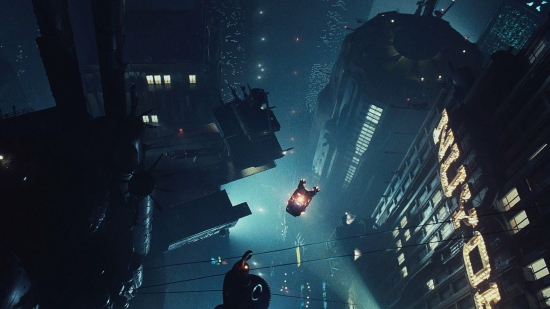

So let’s talk about Bladerunner. I think back to watching the film when it was released, having gone in without any knowledge of it other than that it was set in the future (I had seen some clips on one of the morning TV shows, but had not read any reviews, and didn’t even know it was drawn on a Philip K. Dick novel). I found myself pulled deeply, immersively, into this dystopian 2019 (the year the film was set). This was a Los Angeles like no other, with colossal buildings and streets so far below they were almost subterranean. All wrapped around a plot with elements of Raymond Chandler, and the Harrison Ford voiceover of the original (not the director’s cut). Speaking of that, I am one of the apparent minority that preferred the voiceover version, probably because I’m such a fan of 1940s era film noir.

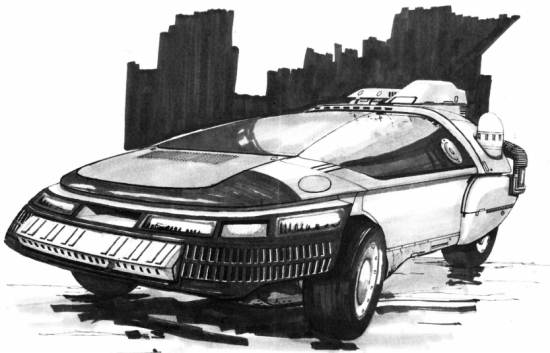

And then there were those vehicles, all drawing on Mead’s vast experience as a designer for companies like Ford and Philips. Mead spent two years developing concept cars — i.e., vehicles of the future — for Ford Motor Company’s Advanced Styling Studio, and launched his own design firm in 1970. He had clients worldwide, particularly in Japan (Sony, NHK and Honda, among others). His film and animation projects made him wildly popular in Japan, a place that obviously fascinated the man, as witness the Japanese aura of Bladerunner.

Image: A corporate ‘spinner’ in an early concept drawing from the Bladerunner Sketchbook.

‘Spinners’ wafted the wealthy in the stratified upper reaches of the city wherever they wanted to go, and served the police for their patrols, but these were not the flying cars that have often been conceptualized in science fiction art. Mead’s vehicles were realistic and looked like they had seen plenty of use, utilitarian workhorses with gull-wing, vertically opening doors, with a look that made them equally at home on the street or in the air, where the wheel covers had rotated and the device lifting the vehicle was enclosed within it — no wings or propellers here.

Mead said that Bladerunner was “not a ‘hardware’ movie.’ It’s not one of those gadget-filled pictures where the actors seem to be there only to give scale to the sets, props and effects. We’ve created an environment to make the story believable. The tools and machinery appear only when needed and fit tightly into the plot.”

That quote can be found in the Bladerunner Sketchbook, where you can see how everything from skyscrapers to parking meters emerged, based on principles woven around a fully realized model of the future, one drawing on a career in industrial design. Many of the original production designs here were subsequently modified, offering a rare chance to see how a film’s visuals evolve even as it is in the latter stages of production.

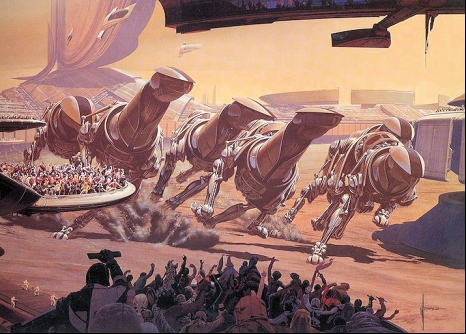

Syd Mead started doing movie concept work in 1978, four years before Bladerunner. As an aside, my friend Al Jackson, who is as good at ferreting out information about writers as associate editor Larry Klaes is at reverse-engineering films, told me that Mead did some concept art for a planned remake of Forbidden Planet that was never made. I wonder where that artwork is today? Al describes Mead’s earlier work as looking a bit like Saturday Evening Post illustrations, but adds that he then began to produce an other-worldly science fictional art unlike anything else in the market at that time. Al sends along a piece called “Race of DGXXX,” though neither of us knows where it originally ran.

The image below is the one that caught my eye on the morning TV show that was talking about Bladerunner. I was in a motel room somewhere in the Cumberlands in 1982, getting ready to check out and head west, and I remember standing there with my suitcase open on the bed behind me mesmerized by the visuals. This was a movie I had to see, and I did so as soon as possible.

I had never heard of Syd Mead back then and only found out that Philip K. Dick had died by watching the final credits on the film. But I had never seen as fully visualized and boldly executed a vision of the future as this one. Those of us wrapped up in the literature of the imagination and the filming of same have suffered a grievous loss with the death of Syd Mead.

A final thought: Apple TV+ is in the pre-production phase for its version of Asimov’s Foundation, with Jared Harris playing Hari Seldon. It will be interesting to see how the visuals on Trantor turn out!

I remember walking down Tottenham Court Road in London one evening and being struck by how much it reminded me Syd Mead’s Bladerunner world – a dark night, neon lights, a clash of different cultures in one big melting pot with oriental restaurants, Eastern European shops, hustle and bustle, voices in a dozen different languages around me. The irony is that in general, in reality 2019 looked pretty much the same as 1982! Maybe there’s a lesson there, that perhaps we imagine change to happen faster than it really does. On the surface, 2050 will probably look pretty much the same as 2020 does.

Syd Mead’s designed also influenced a generation of science fiction designs. From the sterile cleanliness of science fiction design in the 1970s, now film-makers wanted the dark grittiness of Bladerunner. I’d love to see some fresh takes on how a future city might appear. Maybe something with a greater emphasis on bioengineering, or something totally alien, a bit like Alastair Reynolds’ melding plague-ridden Chasm City (albeit that’s on a different planet).

I can attest to the impact of visuals. I was often inspired by the cool vehicles I grew up watching on TV & movies. I am also a fan of Syd Mead. I wonder how many of these on my list affected others too:

– Seaview submarine along with its Flying Sub

– Cousteau’s Diving Saucer

– Nautilus from Disney’s 20,000 Leagues

– Amtronic (http://www.scalemodelnews.com/2012/09/back-to-futures-past-with-amtronic-124.html)

– 2001 Moonbus and EVA Pod

– Trek’s Enterprise (1st movie version my favorite)

– Trek’s boxy Galileo Shuttle (like a flying panel van)

– Space 1999 Eagle (blowed up real good)

– Millennium Falcon (intro to grunge & greebly style)

– The aforementioned Blade Runner’s spinner

– City in the movie Tomorrowland (and things like it)

– Cloud City from Star Wars – Empire Strikes Back

– etc.

Thanks for writing this. This kind of imagery really draws me in and both Blade Runner and Man in the High Castle are the best examples of it. I wish there were more of this kind of science fiction show than the usual stuff which is often pretty unimaginative.

“While I wasn’t much taken with the way The Man in the High Castle’s plot played out on TV, I did go ahead and watch every episode because I found the visuals so entrancing. The idea of a Japanese occupied California was fully realized, with touches like the Japanese fascination with American pop culture and antiques, the use of the I Ching by the trade minister (Dick’s fascination with and use of the book in his plots is well documented), and the interactions between the Nazi government in America and the Japanese one, with glimpses of Concord-like airliners bearing swastikas, were compelling and compulsively watchable.”

I don’t know if that was you, Paul, who knocked the Man in the high Castle, but if it was then all I can say is I hope you never get to write any kind of TV script. The Man in the high Castle was brilliant screenwriting and I don’t want to get into why, but I can tell you its head and shoulders above what Philip K Dick would ever write in his life.

As for the movie Bladerunner I’d certainly agree that it was a good movie and great visuals. The quality of Blade Runner that was to me the most significant thing was the fact that there was a subtlety concerning the genetically modified people that were being used as off world slave labor. It brought up, Of course, the question as to whom or who is the master and who is the slave and what defines what a slave is. It presented an earth which seems to be on the verge of collapse and it tends to entice the viewer to ask the question, would you be better off on another planet or tough it out here. Glad to see they didn’t make any kind of remake of Forbidden Planet. Anybody who touches that masterpiece would convert it into a disaster.

Blade Runner(82) is a stand out film for lighting. Creating that dark(literally) otherworldly and disturbing atmosphere with directed light, stark silouettes and long shadows.

The visuals and emotions of the rooftop fight are burned into my memory. Roy’s death scene a highlight (despite the heavy handed symbolism) of cinematic history.

I too am a Syd Mead fan. I own his coffee table art books:

Sentinel

Sentury,

and Oblagon.

I also own his Studio Image books (1, 2 & 3)

And of course, the Blade Runner sketchbook.

According to an insert in my copy of Oblagon, “The Running of the DRGXX” is one of a set of custom limited edition (250) prints. [32″x25″] Studio Image 1 also has rough sketches for “Running of the Six DGX”.

Sketches for “Forbidden Planet” can be found in Sentury pp82-85.

My take on TMITHC was that the pilot episode that AMZN pushed out for voting was gorgeous. Then when it won, the writers had to scramble to make it into a season. The result was a season where you could watch episodes 1 and 10, and ignore the middle 8. With teh success of the first season, the writers buckled down to create far better story arcs and far better seasons. I will say that I was a little confused by the ending as it wasn’t clear to me why all the parallel universes were now able to have their “refugees” cross universes. Having said that, I concur that it was a very good treatment and far surpassed the novel.

I find it interesting that Blade Runner, like <2001: A Space Odyssey initially did very poorly at the box office, but then grew its audience to become a cult movie. I do think the subsequent cuts got better (I didn’t like the theatrical voiceover to explain things). I suspoect that after seeing the original, the various “director cuts” could dispense with the voiceover as the movie was well understood by then. Removing the “happy ending” of the theatrical release was smart too. (What were those studio execs thinking?).

I’m not sure where I read it, possibly a Clarke essay on 2001, or in “The Making of 2001”, but there was a note that when Kubrick asked for what would a city look like in 2001, he was taken out of the studio and shown the view. “It will look like this”. City landscapes change very slowly, and built cities like London tend to stay very constant with a slow turnover of buildings. Shiny new office buildings may emerge, sometimes there is massive slum clearance. The more obvious changes are ephemeral – shops change, signage styles change, advertised products change (The US had a lot of spirit advertising in the 1960s, which has long since disappeared). But architecture and city layouts last a long time. London has streets laid out from the time of Christopher Wren (17-18th century). Street names may reflect local geography, long since removed or buried.

Syd Mead had it exactly right in Blade Runner, where new technology encrusted the old. Consumers add solar panels and satellite dishes to roofs, removing the old tv aerials. ATMs are added to walls to dispense cash. Vending machines pop up everywhere. Cars become more complex, with screen displays and guidance electronics, either built-in or added by customizing shops (remember adding radios, seat belts, alarm systems? In the 1990s, LA had that brown sky too. Today look to Beijing and Kolkata for that polluted look. The NY Metro still beats Blade Runner for its grungy look, IMO. While I didn’t like Blade Runner 2049 as much, Villeneuve did update the technology as one might expect after 30 years. Sadly we don’t yet have Nexus Replicants. Instead, we just take humans, shorten their lives with stress and unaffordable healthcare, and work them very hard. The “Basic Pleasure Model” like Pris is just a selection from the sex trafficking rings. Chu wouldn’t be an eye designer, but part of an organ-legging scam. The creepy Voigt-Kampf emotion testing machine that Deckard uses to find replicants is now being emulated by AI systems purporting to detect different emotions (hah!). Had Ridley Scott known that DNA testing would have been so easy by 2019, Deckard could simply have taken DNA from the environment and his targets to find the replicants, Gattaca style.

PKD was not one of the great story tellers of our time. A typical PKD novel starts with an intriguing idea, develops it a bit, then stops. This was partly due to the level of pay he received, which required him to produce three novels a year to make a living. So, on discovering he was approaching his 45,000 word count minimum requirement, he would do a quick wrap-up chapter and turn the manuscript in.

This open-ended arrangement, however, is what makes his works so popular to adapt as a director can take his original ideas and play with them.

I thoroughly enjoyed the adaption of A Man in the High Castle as I thought that the writers took the ideas, and the hanging threads from his book, and extrapolated them with a chilling brilliance.

Seeing the original Bladerunner in a movie theater, I was visually stunned to the point of dizziness seeing the spinner ascending between the buildings in the dark city scene. In science fiction, the ‘believe-ability’ factor is what brings us fully us into the real of the imaginable. So the visuals, so well considered and executed, help an audience suspend disbelief and help to open the doors of their perception.

But important elements of PDK’s original novel, such as the emergence of the ‘Mercer’ religion based on technologically-assisted empathy, were left out of the movie. In the book, the environmental collapse causes people to miss the all animals now extinct or very rare. But you would have to be extremely rich to own a real sheep, so an electric one will have to do. This emotional response spurs on the technological replication of animals — but also human simulacra as an extension. However, in the movie it is the replicants who exhibit human feeling more than the biological humans, who are either callous or incredibly cruel.

Many of the elements of Amazon’s version of The Man In The High Castle were sourced from Phillip K Dick research and notes made after publishing the novel for a potential sequel. These include the Nazi’s creation a technological means of transiting the multi-verse, Heissmann’s realisation of a Nazi mega-engineering plan to drain the Mediterranean Sea for farmland, and the nuclear extermination of Africa’s indigenous population incorporated as background to the TV story. Visually, Amazon’s TMITHC did a great job – particularly liked the rocket-fuelled SST and the Japanese fleet in San Francisco bay. Eerily, we see a vision of a Fascist USA in which media propaganda and public relations are used to bring about a ‘year zero’ that nullifies history and redefines reality in the way its rulers wish it to be. It is only the traces of other possibilities, represented by visitors from alternative worlds, that challenges the monolithic iron grip that animal pig-farm populists have over the minds of ordinary people who value the security of their families above all else (hint, hint).

PKD was a prodigious author who was never short of new ideas for his stories. While the writing style may have often been ‘pulp fiction,’ what I liked most about his writing related to his examinations of the nature of reality itself. Truth being stranger than fiction: his story concepts gradually invaded his personal life, as if from another dimension, and the line between fiction and reality became blurred. PKD began to experience the multi-verse, as Hawking has seriously theorised, more and more as his day-to-day reality. I await his next alternative novel or film can.

“… PKD began to experience the multi-verse, as Hawking has seriously theorised, more and more as his day-to-day reality…”

No – PKD began to experience the impact of his earlier illicit drug use and its ramifications more and more as his day-to-day reality

I suspect AMZN’s decision to do more seasons was partly based on our current geopolitics. Smith, after all, was an American who had joined the Nazis. His actions were particularly made clear in his back story in season 4. The meaning was hardly subtle.

PKD was very inventive, even if most of his stories involved questioning reality, various mind-altering drugs, and mental illness. His novels and short stories have been the basis for more SciFi movies than any other writer, although most are pretty poor IMO. BR was a standout exception, mainly due to Ridley Scott’s high-quality craft at the time.

I agree with you that many of the important socio-religious ideas of the novel were dropped in the movie. Even the owl in the Tyrell building is artificial, while it should be real if the movie adhered to the novel’s ideas, while Deckard has an artificial sheep on the roof of his conapt building as he cannot afford a real animal.

While movies are rich visual presentations, they are undeniably light on context and nuance. Add too many different ideas and audiences get confused (c.f. 2001: A Space Odyssey). I suspect that is why some of PKDs better novels have not been made into movies – to do them justice would be extremely hard to do and make a profit.

“…Even the owl in the Tyrell building is artificial…”

Wasn’t the owl and a real owl, even if it had been synthesized in a lab, rather than an egg?

As artificial as a replicant. In the movie, the replicants and artificial organisms were “manufactured” (remember the tracking down of Zhora’s snake). Today, we might say gene engineered. In the novel DADOES and others dealing with simulated people, the manufacturing was more similar to a machine.

In the movie, the point was to question what was human and the morality of killing (not destroying, and calling it “retirement”) the replicants. In the novel, there was no question about the simulacra, it was just a matter of detecting them before destroying them.

In following up on your comment that the owl was as artificial as a replicant-I wonder if you would expand just a little bit more on that.

Now I distinctly remember (with no doubt whatsoever in my mind) that Harrison’s Ford’s character was tracking down the origin of the snake used in the act, which was a artificial snake. Now the snake was identified because the scale from the snakes skin had a embedded identification number, which was genetically imprinted into that particular scale.

Now I make that extremely fine distinction to point out that while the snake had a ID built into its genetics, so that it could be identified, the snake was just as real as a snake that we would see today if we were to grab a snake out of the wild.

In other words, the snake was a snake. It’s just that it had built in the ability to generate within its tissue and ID identifier. So what defines real versus something you call a replicant?

That’s what I meant when I said that you had the question about whether something was ‘artificial’ versus something that wasn’t. The only difference between artificial and what we call real was that the organism had the built-in ability to have been shown to generate its own ID tag. Thus, the origin of my question.

I understand where you are coming from. However, note that when Deckard enters the Tyrell building, he asks about the owl.

I think this supports my claim that the animals, including teh snake are “manufactured”, even if that might mean they were grown, rather than assembled. However, the fact that Chu is making eyes that are part of the replicants suggests to me that the replicants are not grown like organisms, but assembled from parts. I would suggest that this means all teh animals are.

Where Scott changes the context from teh book, is that real animals are rare and expensive in DADOES. In BR, it is the manufactured animals that are expensive (as per the dialogue above). This seems like a natural mistake by Scott’s writers to make in a world that we live in where manufactured simulated animals are far more expensive than living things. Well, probably not a mistake, but something that would make more sense to an audience. Maybe in a few centuries, that opposite will be true, especially after the 6th extinction has resulted in the loss of many of the charismatic megafauna of Earth.

In the case of the ID on teh snake scales, this could not be a result of growth, but rather must have been added after the snake was fully grown. That doesn’t mean the snake couldn’t have been grown and the ID added like a nanoscale brand, but it would make more sense in the context for the snake to have been manufactured as per the replicants and the IDs added as part of the manufacturing process, perhaps to the cultured scales when added to that snake’s skin.

Because of the theme of the movie, the manufacturing process is deliberately made obscure so that we can identify with the replicants as being [super]humans, not androids or robots. The replicants must be created quickly as they need to have implanted memories as they don’t live a life to create them. A key point in teh movie is Rachael’s upset when she realizes her childhood memories are implants, and not due to her experiencing them as a child. In BR 20149, another Rachael is manufactured to influence Deckard. This must be manufactured quickly. Even if “tank grown”, the development would have to be very fast for it to be ready as a contingency.

That’s my 2 cents.

A big part of the creation of the right mood in Blade Runner was the music. I think it had one of the most powerful film scores ever in a Sci Fi movie. Hats off to Vangelis!

I completely agree with the power of the music. BR’s music fit well and can stand on its own. That music added much to the feel of the whole movie. On a related note, I wonder if Star Wars would have had as much impact if its music had be less grand.

Syd Mead, Tony Masters (2001) Geiger (Alien), Dan Weil (Fifth Element) all amazing visual imaginators and there are many others including Irwin Allen on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and Lost in Space; TV shows that are the reason I became a designer.

But there’s something new afoot. Art created by GAN techniques (Generative Adversarial Networks) using neural networks that are trained on imagery and compete against each other. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generative_adversarial_network

These are now delivering EYE-POPPING aliens, spacecraft, and landscapes.

See for example:

https://www.instagram.com/ganbrood/ by Sebastiaan Uterwijk

Looking at the images gives me the chills; like the scene in District 9 when the hovering mega-craft is first seen. I thought “that’s how it’ll be: overwhelming.”

Arrival’s design was so-so except for Wolfram’s mathematical language. If anyone is not familiar with that check out: https://blog.wolfram.com/2017/01/31/analyzing-and-translating-an-alien-language-arrival-logograms-and-the-wolfram-language/

And lastly there’s No Man’s Sky. A procedurally generated universe. A bit gamy looking but it’s in real time and if you have the time (I don’t) it’s a creative adventure. https://www.nomanssky.com/

The molecular chemistry of proteins is now handled by Generative Adversarial Networks.

In a Matrioskha brain with Generative Adversarial Networks as a feature in a basal level of a complexity beyond human conception, could entire (xeno-?) biological ecosystems be designed and synthesized?

I am doubtful as it would be hard to create the objective functions to operate against. I think those matrioshka brains would be better suited to running evolutionary algorithms to generate those ecosystems. GANs might be used to fine-tune good evolved versions if they are more efficient at that task than genetic algorithms.

The bigger picture might be a distant Matrioshka brain evolving a whole range of organisms designed to work in different planetary types, creating the physical organisms, and seeding those worlds as experiments. A really advanced one might just be able to create a world in 6 days with a biosphere containing an evolved biology including a pair of humans. On the 7th day, the brain rested and dreamt of even more interesting experiments… ;) A Matrioshka brain using quantum computing would be truly god-like in its capabilities, an awesome example of Clarke’s 3rd law:

Thank you for those links. That was totally new to me.

You bet Marc!

Here is what I could find regarding Syd Mead sketches for that proposed Forbidden Planet remake, which in all honesty I am glad has never been made:

https://io9.gizmodo.com/concept-art-for-the-forbidden-planet-remake-that-never-1601600000

http://sydmead.com/syd-mead-forbidden-planet-sketch-02/

Two more Forbidden Planet remake sketches from the official Syd Mead Web site:

http://sydmead.com/syd-mead-forbidden-planet-sketch-01/

http://sydmead.com/syd-mead-forbidden-planet-sketch-03/

Again, nothing to Syd, but FP does not need to be remade, reimaged, etc.