Mention red dwarf habitable zones and tidal lock invariably comes up. If a planet is close enough to a dim red star to maintain temperatures suitable for life, wouldn’t it keep one face turned toward it in perpetuity? But tidal lock, as Ashley Baldwin explains in the essay below, is more complex than we sometimes realize. And while there are ways to produce temperate climate models for such planets, tidal lock itself is a factor in not just M-dwarfs, but K- and even G-class stars like the Sun. Flip a few starting conditions and Earth itself might have been in tidal lock. The indefatigable Dr. Baldwin keeps a close eye on the latest exoplanet research, somehow balancing his astronomical scholarship with a career as consultant psychiatrist at the 5 Boroughs Partnership NHS Trust (Warrington, UK). Read on to learn a great deal about where current thinking stands on a subject critical to the question of red dwarf habitability.

by Ashley Baldwin

“Tidal locking”, “captured rotation” or “spin-orbit locking” etc occurs in most recognised guise when an orbiting astronomical body (be it a moon, planet or even a star) always presents the same face towards the object it is orbiting. In this instance, the orbit of the “satellite” body can be referred to as “synchronous”, whereby the tidally locked body takes as long to rotate around its own axis as to orbit its partner. This occurs due to the primary body’s gravity flexing the orbiting body into an elongated “prolate” shape. This in turn is then exposed to varying gravitational interaction with the central body.

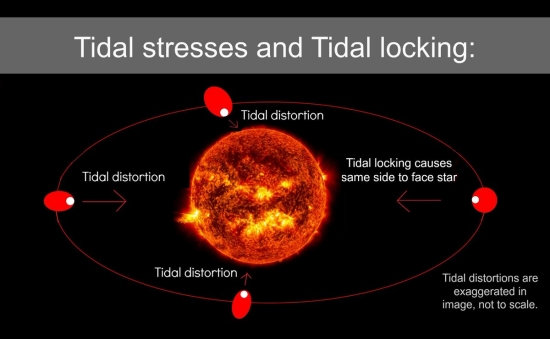

Figure 1: Tidal stresses and tidal locking

As the “orbiter” rotates, its now elongated axis falls out of line with the central mass, which consequently perturbs it as it rotates across its orbit. It thus becomes subject to gravitationally induced torques that can act as a brake — through energy exchange and dissipation, the latter via friction-induced heat loss in the perturbed orbiting body. As M dwarf habitable zones are closer to their central star and their gravitational influence thus greater, it’s easy to see how this dissipated heat can contribute substantially to an exoplanet’s overall energy flux and can even affect its habitability potential – possibly tipping it into a runaway greenhouse scenario. (Kopparapu 2013).

Over millions of years (or more) this process can lead to “orbital synchronisation”. This arises when the orbiting body reaches a state where there is no longer any net exchange of rotation during the course of a completed orbit (Barnes 2010). Leaving a tidal locking state would only be possible with the addition of energy to the system. This might occur should some other massive object (such as a planet, or a star in, say, a binary system) break the equilibrium. If the masses of the two bodies (for instance Pluto & Charon) are similar, they can become tidally locked to each other.

Not all tidal locking involves synchronisation. “Super-synchronisation” occurs where an orbiting body becomes tidally locked to its parent body but rotates at a fixed but quicker rate. A topical example of this is the erstwhile “geosynchronous transfer orbit” (GTO). We see this on launcher specs all the time: “Payload to GTO”. This orbit is external to geosynchronous orbit, where many satellites start their operational lives, but allows for pre-orbital insertion inclination changes — economically expending less propellant prior to final insertion. Alternatively, such orbits can be used as dumping grounds for non-functioning satellites or related debris, so-called “geo-graveyard belts” (Luu 1998). Simulations suggest many exoplanets could exist in variants of such orbital types.

Gravitational interaction with a central star leads to progressive rotational slowing of a smaller planetary body like Mercury via energy exchange and heat dissipation. This is due to subtle but important tidal force variations across the orbiting body (remembering that gravity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between any two bodies — thus “gravitational gradients” exist across solid bodies, leading to bulges). However, if the initial planetary orbit is significantly eccentric, this effect varies substantially across the orbital period (especially at periapsis — the point of strongest gravitational interaction) and can instead result in a spin-orbit resonance. In Mercury’s case, this is 3:2 (three rotations per two orbits) but other ratios can occur from 2:1 through 5:2 (Mahoney 2013). It’s worth noting that this effect is most pronounced for closer-in planets where the gravitational effects are greatest, so the effect should be even more relevant for the tightly packed exoplanetary architectures (e.g. TRAPPIST-1) that seem to be prevalent.

In extreme cases where the orbiting body’s orbit is nearly circular AND has a minimal or zero axial tilt — such as with the Moon — then the same hemisphere (libration allowing) faces the primary mass.

That said, for simplicity we will now assume that a smaller mass body (exoplanet) is orbiting a very much more massive body (star) — this is the focus of this review, with an unavoidable nod towards habitability.

For reasons of brevity and also pertaining to the exoplanet subject matter of recent posts, we will limit ourselves to the specific case of terrestrial exoplanets and their orbits around smaller main sequence stars.

The time to tidal locking can even be described by the adapted equation :

Tlock ≈ wa6 (0.4 m*R2) / (3 Gmp2 kR5) (Goldreich, Goldreich & Soter 1966); (Peale 1977); (Gladman 1996); (Greenberg 2009)

Where Tlock is “time to tidal locking”, w and k are constants which can be ignored for simplicity, m* is mass of the star, mp is mass of the planet, R is the exoplanet radius and “G” is Newton’s all important gravitational constant.

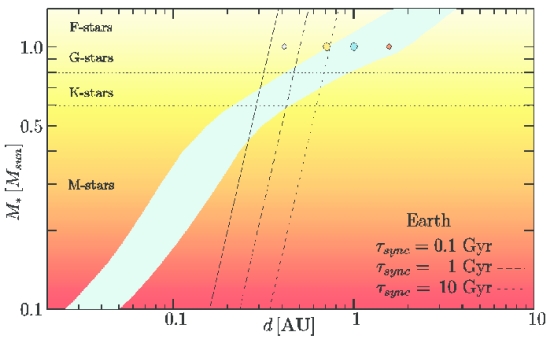

Tlock is substantially lengthened by “a” — increasing planetary semi-major axis (to the sixth power!). Tidal locking time is also increased by 0.4 X m* in this equation. However it is important to remember the context and just how massive a star, indeed ANY star, is — even an M dwarf star — many times, orders of magnitude even, more massive than a planet. A star thus plays the major role in the tidal locking of its attendant planets.

The gravitational constant G ensures that increasing stellar mass will substantially decrease Tlock. All other things being equal, increasing stellar mass is a major factor in reducing time to tidal locking.

Figure 2: Stellar mass & type versus semi-major axis orange / red graph with superimposed Tsync for 0.1,1 and 10 gigayear times for an Earth mass planet. (Penz 2005)

The concept of synchronisation is relatively new, dating back to Stephen Dole’s seminal Habitable Planets for Man at the beginning of the space age in the early 1960s. The concept was purely theoretical, with somewhat arbitrary parameters at this point, but it implied that tidal lock would be a major impediment to the human-friendly “habitable” exoplanets Dole had in mind for his book. It was here that tidally locked orbits and planets in M-dwarf systems were first linked, in a negative way that to some extent still exists today (before we even get to coronal mass ejections, EUV and stellar flares et al !) Atmospheric collapse due to freezing out on the side of the planet facing away from the star is not the least of these problems.

It was only in 1993 that Kasting et al employed sophisticated 1-D climate modelling as part of describing what constituted habitable planets. Habitable planets essentially now meant planets with conditions that could sustain liquid water on their surfaces. This is a rather lower bar than that set by Dole thirty years earlier, but far more applicable and still a pillar of exoplanet science today. More importantly, Kasting’s team also simulated star/planet gravitational interaction.

They did this by utilising the “Equilibrium Tide” model (ET). Refined variants of this have now become THE staple of all subsequent related studies, as it too has “evolved”. The model essentially assumes that the gravitational force of the tide-raiser (star) produces an elongated shape in the perturbed body (exoplanet) and that its long axis is slightly misaligned with respect to an imaginary line connecting the two centres of mass.

The misalignment is crucial and is due to the dissipating processes within the “deformed” exoplanet, leading to evolution of the orbit and spin angular moments. From this, various equations can be created which map out the orbital and rotational evolutionary history of exoplanets over time (see above). ET was originally derived from the Earth/Moon system by Darwin in 1880 before refinement by Pearle in 1977. Iterations vary in subtle but significant ways and are used as the basis for increasingly sophisticated simulations as computing power increases. Barnes 2017 has carried out a detailed review of synchronising and ET modelling (see below).

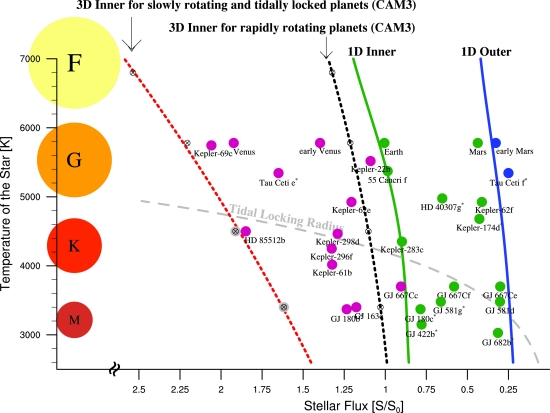

Kasting et al showed synchronisation of putative exoplanets orbiting in the habitable zones of M-dwarfs, stars with a mass of up to 0.42 Msun, within 4.5 billion years. They introduced the now familiar term “tidal locking radius”. Though a big step forward, this had the unfortunate consequence of continuing to propagate a pessimistic view of habitable exoplanets orbiting such stars. Importantly, stellar mass was still viewed as the major if not sole cause of synchronisation. The graph below (from Yang et al 2014), though based on sophisticated modelling, still captures this type of thinking. Here various habitable zone model ranges are superimposed on a graph of relative stellar insolation (and star type) versus semi-major axis examples of known exoplanets, adding realistic perspective. You will note also that for a 0.42 Msun star, with a temperature around 3500 K, the 1-D inner habitable range is very close to the value attributed to recently discovered TOI 700d — mid-80s percent.

Figure 3: Temperature of star versus stellar flux graph with superimposed coloured star classes and dashed gray “tidal locking radius” line.

The effects of other factors — such as starting orbital eccentricity (already encountered above with Mercury), baseline rotation rate, the presence of companion bodies (Greenberg, Corriea 2013) thermal tides arising from atmospheres (Leconte et al 2015), and stellar and planetary interiors (Driscoll & Barnes 2015), orbital tilt (Barnes 2017) — were not considered. As can be seen, it has only been over the last five years or so that these things have been added to simulations. Indeed, the results of these studies very much alter the whole tidal locking paradigm with particular relevance to habitable zones, which despite refinement (Kopparapu 2013, Selsis 2007) have only changed slightly, a big compliment to Kasting’s work in 1993.

Taken altogether, habitable zone planets of M,K and G stars all have the potential to become tidally locked. Not just M dwarfs — though their potential remains very much the greatest and especially for < 0.1 Msun stars such as TRAPPIST-1. Even the Earth, had its starting rotation been greater than just three days, according to Barnes 2017, might have become synchronous.

For the sake of brevity, this review has largely focused on stellar mass as a major driver in exoplanetary synchronisation. As can be seen above, as knowledge in this area progresses, other processes come into account. It is also becoming increasingly difficult to tease these out from drivers of exoplanetary habitability. So to this end we must look in more detail at some of the factors named above.

The planet Venus is unusual in many ways, but one in particular stands out: its retrograde and slow rotation rate that is longer than its orbital period. Why? What makes Venus different? One factor is that it is a rocky planet with a substantial atmosphere (92 bar at its surface). We all know about the infamous runaway greenhouse effect this drives, making Venus the hottest planet in the Solar System despite being further from the Sun than (spin/orbit resonant) Mercury. However, does this atmosphere have any other effects?

On Earth, the day/night cycle leads to variations in heat distribution in the atmosphere. It is known that the hottest time of day on Earth does not occur when the Sun is at its zenith and thus nearest to the Earth, but rather several hours later. This is because of thermal inertia. There is a delay between solar heating and thermal response, leading to mass redistribution. As the atmosphere and the Earth’s surface are generally well linked via friction, this will give rise to non-negligible thermal torques.

These torques are akin to the torques arising from the Sun’s uneven gravitational interaction with the Earth described above, though not as potent. On the Earth with its extended 1 AU orbit, they are largely inconsequential, but for 0.3 AU nearer Venus, they become significant. Depending on their direction, they can either slow up OR speed up planetary rotation, but either way they help to resist synchronisation. Over time, torques arising in Venus have acted to slow down its rotation, so much so that it has reversed to the retrograde pattern we see today.

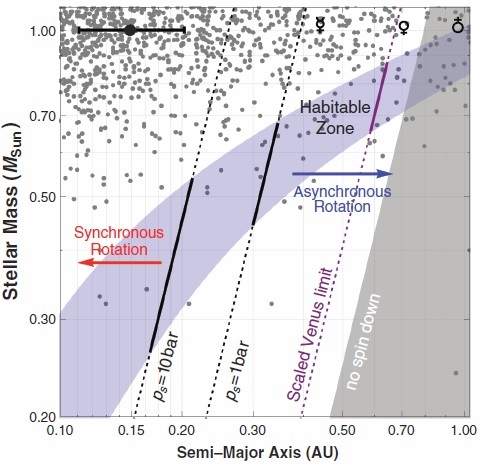

So if this is true of Venus, how about exoplanets? Can these atmospheric torques resist or at least delay synchronisation and tidal locking in vulnerable areas around a star? This has been extensively modelled by Leconte et al 2015 and the answer was a resounding yes, especially for smaller, less luminous stars with close-in habitable zones, and not just for exoplanets with 90 bar atmospheres, either. Even 1 bar Earth-like atmospheres could help resist synchronisation for the habitable zones in stars of 0.5 Mearth – 0.7 Mearth.

Ten bar atmospheres were simulated and shown to resist synchronisation even for habitable zone planets orbiting 0.3 Mearth stars (mid-M dwarfs). These are the high bar “maximum greenhouse” CO2 atmospheres that are postulated to occur in the outer regions of stellar habitable zones. But there are limits. Venus’ 92 bar atmosphere is ironically so thick that most of the incident sunlight that isn’t reflected back into space is either absorbed or scattered before it can reach the planetary surface and exert the driving effect of thermal torques (Leconte et al 2015).

Figure 4: Red arrow synchronous rotation / blue arrow asynchronous rotation graph (Leconte 2015).

Orbital synchronisation and exoplanet habitability remains a contentious theoretical field that is subject to continual debate and constant change. Modern Global Climate Modelling (GCM) has become a sophisticated sub-science. Using an earlier iteration of GCM, Yang et al showed in 2013 that synchronised M-dwarf habitable zone planets would form thick cloud banks above their sub-stellar point. This would then reflect much of the incident stellar flux, thus reducing the energy reaching the surface. In turn, this would reduce the overall energy reaching the planet and so reduce global temperatures. The net effect in theory is to extend the stellar habitable zone inwards. However, the same author collaborated with Wolf and Kopparapu in 2016 to apply an updated 3-D model to the same problem. This showed that a sub-stellar cloud bank could not form, or would form and then move, a result effectively rebutting the 2013 findings and moving the habitable zone back to its original pre 2013 starting point. Expect more of this !

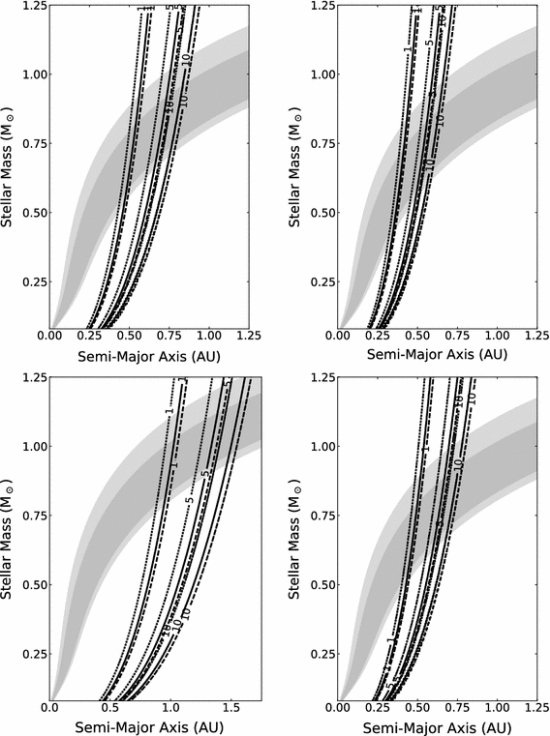

So, all things considered, just how easy is it for an exoplanet to become tidally locked and just how easy can habitable zone planets become tidally locked ? Barnes 2017 attempted to address just this question for exoplanets in circular orbits. He applied two well recognised refined variants (CPL left, CTL right in the graphic below) of the ET to two model populations of exoplanets orbiting differing stellar masses, and ran thousands of giga-year simulations for each (think of the computing power and time!) One population had a starting orbital period of 8 hours and an orbital tilt of 60°. The other had a starting period of ten days and a tilt of 0°. This produced the four outcomes illustrated below. The superimposed grey shading represents the latest habitable zones (Kopparapu 2013) iteration, with the dark grey representing the “conservative” and the light the “optimistic”.

Figure 5: “Four in one” black and white stellar mass vs semi-major axis / superimposed greyscale habzone graphs.

These results are indicative and significantly different from the status quo, which is that tidal locking is only something that applies to exoplanets orbiting in close to M dwarf and smaller K dwarf stars. For one thing, even this older paradigm implies that at least some “Goldilocks” stars are not quite as homely as expected (more Kasting than Dole). The Barnes work hints at potential overlap of the habitable zone for potentially a large fraction of K-class and even many G-class stars, driven by factors beyond simple stellar mass. Clearly planets with a slow initial rotation rate and low orbital tilt are at greater risk, as may prove the case. Opposed to this are non-synchronising factors such as, inter alia, higher baseline orbital eccentricities and the close proximity of other orbiting bodies (moons, planets …thinking TRAPPIST-1 and binary stars/brown dwarfs, as with the recently described Gliese 229Ac system).

What this also shows is the inextricable link between orbital features and planet habitability. No more so demonstrated than by Kepler, and likely even more so with its greater number of short orbital period planets, with any potential habitable zone planetary candidates lying within just tenths or less of an AU from their parent star. This is very much in the “red arrow” synchronous zone in the Leconte graphic above.

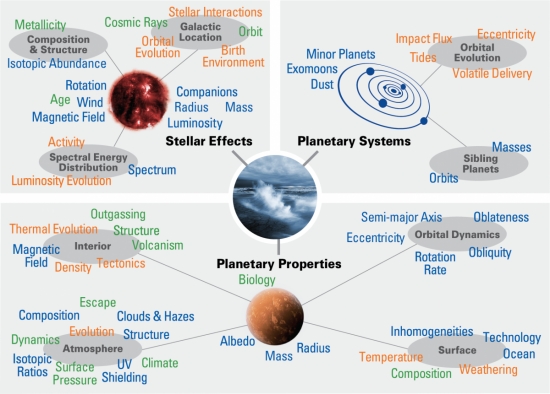

There are now over 4000 known exoplanets. The current focus is on their “characterisation” and this is largely about atmospheres and biosignatures. However, it is obvious that we need to know far more about their evolving and historical orbital properties. This is a part of a process of determining habitable planets/zones, which are about so much more than stellar mass.

Most of the exoplanets discovered already by Kepler et al orbit close in to their stars, including those few in the potential tidal lock habitable zone. Ongoing Doppler photometry and TESS will identify thousands more such exoplanets, many of which will be even closer to their latest star given TESS’ shorter 27 day observation runs. TOI 700d and Gliese 229Ac are just for starters. Hopefully the search for habitability will expand to encompass the unavoidable connexion with planetary orbital features.

Know the star to know the planet, but know the orbit to know them both.

Figure 6: Stellar effects/planetary properties/planetary systems (Meadows and Barnes 2018)

References

Barnes,R. Formation and evolution of exoplanets. John Wiley & Sons, p248, 2010

Barnes, R. Tidal locking of habitable exoplanets. Celestial mechanics and dynamical astronomy Vol 129, Issue 4, pp 509-536, Dec 2017

Darwin, G H. On the secular changes in the elements of the orbit of a satellite revolving about a tidally distorted planet. Royal Society of London Philosophical Transactions, Series I, 171:713-891 ; 1880.

Dole, S H. Habitable Planets for Man. 1964

Goldreich, P. Final spin rates of planets and satellites. Astronomical Journal, 71, 1966

Goldreich, P., Soter, A., Q in the solar system. Icarus 5, 375-389, 1966

Gladman, B et al. Synchronous locking of tidally evolving satellites. Icarus 133 (1) 166-192, 1996

Greenberg, R. Frequency dependence of tidal Q, The Astrophysical Journal, 698, L42-45, 2009

Kasting, J. F. Habitable zones around main sequence stars. Icarus,101 d 108-128 Jan 1993

Kopparapu, R K et al. Habitable zones around main sequence stars: New Estimates. The Astrophysical Journal, 765;131, March 2013

Kopparapu R K, Wolf E, Yang et al. The inner edge of the habitable zone for synchronously rotating planets around low-mass stars using general circulation models. The Astrophysical Journal Volume 819, Number 1, March 2016

Luu, K. Effects of perturbations on space debris in super-synchronous storage orbits. Air Force Research Laboratory Technical Reports, 1998

Mahoney,T J. Mercury. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013

Meadows V S, Barnes R K. Factors affecting exoplanet habitability. In Handbook of Exoplanets P57, 2018

Peale, S J. Rotation histories of natural satellites. Burns, J A, Editor, IAU Colloquium 28; Planetary Satellites, p 87-111, 1977

Penz,T et al. Constraints for the evolution of habitable planets: Implications for the search of life in the Universe: Evolution of Habitable planets, 2005

Yang, J et al. Stabilising cloud feedback dramatically expands the habitable zone of tidally locked planets. The Astrophysical Journal Letters: 771:L45, July 2013

Yang, J et al. Strong dependence of the inner edge of the habitable zone on planetary rotation rate. The Astrophysical Journal Letters: 787:1, April 2014

Hi Ashley, very interesting article. One question from the extract below though:

“It is known that the hottest time of day on Earth does not occur when the Sun is at its zenith and thus nearest to the Earth, but rather several hours later.”

Agreed that 3 pm, plus or minus, is warmer due to thermal inertia, just as mid January in the northern hemisphere is colder than December 21st. What I don’t understand is the “and thus nearest to Earth” comment. The Sun is always directly overhead over some point of Earth and thus at zenith all the time somewhere. Solar zenith is not related to our distance from the Sun. Our orbit around the sun is elliptical. We are closest in January and farthest in July. Maybe I missed something.

I was using “zenith” here in its broadest generic sense as a point directly above a specific location rather than in a formal celestial sphere sense.

It would be interesting to know what effect the creation of the Moon had on the rotation of the Earth. Would the Earth be tidally locked if not for the creation of the Moon?

Known examples plenty: Venus is not tidally locked. (but the situation is maybe even worse than being tidally locked.) the best analogy is probably the situation of Mars though: a 24 hour day but with much bigger swings in seasons and greater instability variations of its axis over long periods of time.

Very good explanation of tidal locking and synchronization.

Are you intending to do a follow up to look into the issue of tidal lock (and synchronization) on habitability? Is it a “life killer”, or does it offer a “temperate” zone on the terminator? Does it offer some shielding from high energy flare radiation?

Thanks Alex.

If you read the many excellent reviews of this subject by Meadows and Rory Barnes in particular, referenced above ( they are all great reads ) the general consensus is that synchronous rotation is not a habitability killer. This is the view of much ( but not all of course) of the astro/geophysics community.

With enough atmosphere and/or ocean, heat can be distributed around the putative tidally locked planet enough to atmospheric collapse via freeze out on the “dark side” (although as you can see from the Leconte graph atmospheres help resist synchronicity ) .

The thing that troubles the scientific community far , far more is the extended pre-main sequence luminosity of all but the largest M dwarfs. Something Barnes has demonstrated in his sophisticated simulations too.

That’s why JWST finding CO2 in TRAPPIST-! d,e and/or f via transit spectroscopy is so vital ( and difficult – involving a sizeable chunk of the time et aside for exoplanet science) as that will show that secondary atmospheres can develop and persist around even active late M dwarfs of which TRAPPIST-1 is a representative example.

Hi Ashley,

Nice review, thanks.

Regarding the effects of the elevated stellar luminosity during the long pre-main sequence for M dwarfs, Kenyon and Bromley wrote a paper a few years ago pointing out that planet formation can occur well outside the habitable zone up to a billion years after the formation of an M dwarf. In about ~5 percent of their simulations, the planet ends up in the habitable zone so this may be one way to have planets in the HZ that still have an atmosphere.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1311.0296.pdf

cheers,

David

Thanks David . I am familiar with this work and it is indeed very much my hope although not everyone agrees with this scenario. But it’s important to take away from both this – and the content of my article – that most if not all of what is known is based purely on simulation . Until we have hard atmospheric characterisation data from JWST, the ELTs and hopefully WFIRST this will remain the case. Certainly in terms of habitability potential. Not too long to wait though .

Interesting paper, but I have never heard the idea of “thermal torques” before this article. I doubt any effects of a large atmosphere could slow down the rotation or speed of the axial spin of a planet if I have understood this idea presented here correctly. The reasons for Venus slow rotation are some interaction with Earth’s gravitational field and the Sun’s which slowed down Venus rotation since Venus might never have had much axial spin from the start.

Earth got it’s fast rotation or axial spin from a collision with a large body called Theia which gave the Earth the needed kinetic energy and angular momentum as theorized in the large impact hypothesis which is why a Moon is needed for an exoplanet to have a fast axial spin.

Consequently, the Earth will not be tidally locked with the Moon for tens of billions of years if these survive the red giant phase.

I assumed what Ashley meant was either an atmospheric version of the friction from ocean tides, or the effect of the bulge in the atmosphere due to heating having a similar effect to the gravitational bulge as outlined in the post.

Although ocean tide friction was not mentioned, it would be useful to have some orders of magnitude size effects for the various mechanisms that slow rotation.

From the link above it looks like the Earth has added about 3 hours to the length of day since the “Cambrian explosion”. Unlikely as it seems, the day would be 25 hours longer after 4 billion years, i.e. longer than our current day length, suggesting that this rate of rotation deceleration must be increasing over time.

There’s nothing new about the concept of atmospherically induced torques or “tides” . The theory originally dates back to Gold & Soter’s work in the late sixties . It continued unabated till culmination and definitive description with Leconte’s sophisticated computer modelling and simulations of 2015 – cited and referenced here. They are both very real and very potent as is clearly shown in the enclosed graph and related citation .

Levonte’s work is recognised and confirmed in Barnes’ far reaching “tidal locking” paper of 2017. This then goes on to explore the evolution of tidal locking in a wide range of planets of varying mass in varying orbits around the different mass stars – up to an including Earth mass at 1 AU from of a Sun analogue.

Regardless of the Earth’s rotation time before and after the putative (and still debated ) high angle impact of “Theia”, Barnes’ extensive simulation runs show that a moonless Earth mass planet in a 1 AU orbit about a sun mass star could become tidally locked within 4.5 billion years. Unless it’s baseline rotation rate was less than three days.

Pedantic comment, but important. PEMDAS! In the equation, if everything to the right of the solidus is meant be the denominator, as I suspect, then they MUST be enclosed in parentheses or the answer will be wrong by (Gmp^2 kR^5)^2.

No, this is not pedantry. Notation is all important. For example, try to interpret this sentence in the context of that ambiguous equation:

“The gravitational constant G ensures that increasing stellar mass will substantially decrease Tlock.”

It would also be helpful to add explanatory information to a few of the charts (which must be in the original source) since they are otherwise a mystery.

I’m in agreement about the importance of notation here. I’ve inserted the needed parentheses, as per djlactin.

Analyses such as these may help by guidance on where to look and what to look for. That could reset the Fermi paradox.

Yes. As has been pointed out there are a lot of m dwarfs and one thing that has been shown is that these stars seem to possess planets in abundance. If any of these can be shown to harbour habitable planets then the game is well and truly afoot.

Magnetic fields, torque, magma oceans, and the music of the spheres, every time the Earth and Venus come close together she has the same face looking at the earth. A very good read is the book called “A Little Book of Coincidence” by John Martineau all about the graceful music of the solar system’s planets. This pattern is already being seen in the tightly packed planets around red dwarfs. One idea that may also influence these planets are the strong magnetic field of the red dwarfs and the other planets that come so close by each other. Many of these planets are earth to super earth size and have large oceans or large magma oceans beneath their surface, as in the large thick atmosphere of Venus would have large effects on rotation.

The other side of the coin is the possibility of elongated planets as the molten planet forms in the early age of the miniature solar systems. The chaotic nature that developed in these larger planets under the stress of close neighbors and a much closer star would make for variety of Io type planets with higher order aberrations in shape then anything in our solar system.

But what may be most intriguing are planets further out that have solidified enough that their surface is stable but would have a oval shape with oceans on the sun facing pole and glaciers on the twilight world of the opposite pole. In between would be low radiation lands with volcanoes and life migrating back and forth as the tides oscillate the planet. A nice day dream but maybe it will not be too long till we see the beauty of the chaos and its enchanting music.

Thank you Ashley for some very good food for my imagination!

Thanks Michael .

Very good explanation of tidal locking and synchronization, with Pluto-Charon as outstanding examples of total lock.

Larry Niven & I took Pluto-Charon as a guide to our concluding novel in our Bowl of Heaven series. Our last megastructure is a gigantic tubular lifezone between Earth-scale worlds with Pluto-Charon locking. That expands beyond our Bowl ideas and yields an immense system with transport along the axis that deploys using pressure elevators to run the biosphere. The novel is Glorious, out in June. The first two Bowl novels are out in mass market paperback, over a thousand pages!

Thanks Gregory. Very kind .

As ever I look forward to reading it .

I’m glad too if this all underpins just how important tidal locking is in planetary astronomy . Barnes’ findings alone have huge implications .

JWST allowing I’m hoping that with a bit of CO2 on TRAPPIST-1 e and you’ll get even more and exotic fictional opportunity with it in terms of life in M dwarf systems !

If that means a 72 hour day, I thought the Earth was rotating faster than a 24 hour day after the Moon was formed and has since slowed down. Can you explain this?

Nearer to five hours according to simulations.

The 72 hour period for an Earth mass planet around a sun mass star is simply one of many hypothetical permutations Barnes ran through his (literally) thousands of sophisticated simulations over ‘giga years’. Counterintuitively showing that under arbitrary circumstances even terrestrial mass planets can become tidally locked as far out as the hab zone of early G stars.

All this based around two refined variants (see ‘ four in one ‘ graph and accompanying text) of the established and robust ‘equilibrium tide’ model that was in turn derived from the same maths that created the very simplified demonstration equation cited above .

Venus had oceans earlier but they were evaporated into space and a lot of water was lost from atmospheric stripping based on the DH2O ratio being higher in Venus atmosphere than Earth’s, a two to one ratio. Maybe the weight of the atmosphere or it’s torque slowed down Venus and gave it a retrograde rotation.

There does not have to be synchronization to have tidal locking, e.g., Mercury.

Alex Tolley, The reason why the Earth’s rotation is being slowed down by the tidal forces of the Earth and the angular momentum of the Earth’s axial spin or rotation is being transferred to the Moon’s orbital momentum so the Moon is slowly moving further away from the Earth a few centimeters per year. In the distant future we won’t have total eclipses anymore. At the same time the Earth is gaining time in it’s daily revolution which slowing down a small amount like one and one half miliseconds per century. Kopal 1979, The Realm of Terrestrial Planets.

This indicates that the Earth had to be spinning faster in the past. There is geological evidence: Scallops make one line on their shells every day which is visible under the microscope. They are the deposits of calcium carbonate made every day on their shells everyday so we know the Devonian year had to be 400 days long instead of 365 as today; the scallops have 400 lines on their shells. Also the tides were larger and came further into the land shown by fossil evidence, so that indicates the Moon had to be closer to the Earth and the gravitational tidal forces were greater. Lyle, 2016, The Abyss of Time. Library book so I don’t have the page number.

Kopal’s Book, says in the Cambrian there were 500 days a year with only 21 hours a day. Devonian: 380 days a year with a 21.6 hour day. Carboniferrous 290, and 22.6 hour day, Upper Crataceous, 23.67 hour day etc. Library book.

This is the point I was trying to make. Using your example of a 21 hour day in teh Cambrian (0.55 bya), that is a decrease of 3 hours. Now extrapolate back to 4 bya and the decrease is now 21.8 hours. So the day length was just 2.2 hours. If the Moon was formed 4.5 bya (a tad early), the day length would be MINUS 30 minutes. I seriously doubt that Earth had such a rapid rotation rate even after a collision with the body that formed the Moon. While the effect of the Moon receding is due to momentum transfer, the key point is that it is due to the tidal friction. But when the moon was much closer, those tides would have been much larger and the frictions concomitantly higher as well, implying an even faster slowing down of the Earth’s rotation in the past than today. Something must have been different in teh past so that these extremely short daylengths cannot have been correct even using the more recent daylength calculations, and assuredly even faster [!] when the Moon was closer and the tides higher.

Does this make sense, or am I missing something?

A lot , indeed most of its angular momentum was probably lost through tidal interactions with the moon – which is moving further away taking energy with it as it goes . The rotation immediately after the Moon formation impact 4.5 billion years ago is currently modelled at just five and half hours . ( before that, who knows ? – but hazarding a guess – and looking at the non synchronised planets in the solar system whose angular momentum must have arisen from the same accretion disk – somewhere between 8 and 20 hours ) It then reduced over the next 4 billion years , simulated at about 21 hours by the pre/ Cambrian 600 million years ago .

The deceleration since then has increased at a greater rate – apparently due to extended periods of severe glaciation. ( without going into detail here – but it’s all available on line )

I should have read your comment first. So the relatively recent glaciations are the cause of a more recent faster slowdown in rotation compared to the earlier Earth eras? [My initial calculations used the 2.3 ms/day per century rotation slowdown from the NASA link which I assumed to be current during our interglacial period.]

Try “Analysis of Precambrian resonance-stabilised day length” ; Bartlett C and Stevenson D, Geophysical research letters, July 2016

Yet another mooted “Snowball Earth” heavyweight glaciation

So, the difference the moon-formation-impact made for the Earth rotation was anywhere between roughly 3 and 15 hours. Is there a way to narrow this down this a bit more?

And does the above equation indeed imply that a larger planet decelerates more rapidly (Tlock is divided by mp^2)? That puzzles me, since I would expect a heavier planet to retain more momentum.

Further with regard to the impact of the moon on Earth’s rotation rate, and after checking some more literature (e.g. Williams, G.E., 2000. “Geological constraints on the Precambrian history of Earth’s rotation and the Moon’s orbit”; Bartlett, B.C., Stevenson, D.J., 2016. “Analysis of a Precambrian resonance-stabilized day length”), I wonder which of the effects of the moon has been strongest:

1) Angular momentum transfer, slowing down Earth’s rotation.

2) Atmospheric tidal resonance (as described in this post), stabilizing Earth’s rotation.

3) The moon-creating impact, speeding up Earth’s rotation.

Anyway, I understand now that this is a complex issue, which can work out both for better or for worse on a planet’s rotation.

What about libration? The Moon wobbles a bit in it’s orbit, so that we can see about 60% of it’s surface from Earth.

Is libration likely to be significant in tidally locked exoplanets, especially in those around M-dwarfs? If so,what effect would that have on climate?

Libration , like relativity is function of perspective . Like relativity it also demonstrates underlying theory

Libration is an observational phenomenon arising from oscillations in the gravitational evolution of the Earth/Moon orbital system . As seen from the Earth .

It is the product of three separate features. The first two are evolutionary facts of the tidal locking process and the last a quirk of observational viewpoint.

Firstly: ‘libration by longitude ‘ – the fact that despite orbital synchronisation the Moon’s orbit is not perfectly circular and retains a low eccentricity . So the moon leads or lags in its orbit of the Earth over time . This allows observers from the Earth to see ‘around the edges ‘ of Earth facing hemisphere over the course of an orbit.

Secondly : ‘ libration by latitude ‘ – despite synchronisation the moon retains a small but significant 6.7* tilt with respect to the Earth / Moon orbital plane . This again leads to observers being able to ‘see around the edges’ as above .

Finally the gravitational interaction that leads to synchronisation arises from the centre of mass of the combined system . This occurs on an imaginary ‘straight line’ connecting the centres of mass of the Earth and Moon. So any observer at the edge of the Earth as its rotates can again quite literally see around the edge of the hemisphere as opposed to that seen by a hypothetical observer situated at a point on the straight line ( on the Earth’s surface )

Each individually small but added up these three facets allow 59% of the Moon to be viewed in total.

As time progresses and left to itself tidal locking should reduce the orbital tilt of the smaller body in a ‘two body’ system to zero. Then (and much slower ) it’s orbital eccentricity to zero too. The Earth/ Moon is not a true two body system though ( are any ?) . Nor is the Earth a particularly massive body in the astrophysical terms . As such it is subject to constant additional gravitational perturbation from other solar system bodies not least the much more massive Sun and Jupiter. It is these interactions that drive the oscillations that translate into libration.

So I would guess that ‘pure’ synchronisation never occurs though libration itself though arising from gravitational interaction and orbital dynamics is ‘in the eye of the beholder’ .

In terms of exoplanets it serves to offer a diluted snapshot and insight into the consequences of tidal locking , synchronisation and their evolution .

If there are indeed exomoons out there – and circling tidal locked planets, the gravitational effects of their much closer star will be far more pronounced than that of the Sun on the Earth/Moon system . So libration would likely be even more pronounced.

Thanks for the detailed explanation. So from the perspective of an observer on an exoplanet, would the sun appear to rock back and forth over the course of an orbit? This could be a significant factor on the climate of the terminator.

Excellent post explaining tidal locking very well.

“Know the star to know the planet, but know the orbit to know them both”; I used the first part myself a lot as a slogan, but you taught me the relevance of the 2nd part!

BTW, I think there is a slight error in the text: “stars of 0.5 Mearth – 0.7 Mearth”, I think that should be Msol instead.

I am a bit late in this discussion, due to being busy at work and at home, but this topic, related to stellar type and habitability is one of my favorite. I am familiar with the seminal work of Barnes et al. “The Barnes work hints at potential overlap of the habitable zone for potentially a large fraction of K-class and even many G-class stars, driven by factors beyond simple stellar mass. Clearly planets with a slow initial rotation rate…”. Darn, that’s a very sobering thought! I used to think that high initial rotation was the logical result of the disc accretion into planets. But if a moon-creating impact is necessary for it as well, then high rotation, not tidally locked planets might be much rarer.

With due respect, I have one minor disagreement:”increasing stellar mass is a major factor in reducing time to tidal locking”. Well, since the correlation is linear and solar type stars vary only a little in mass (about from 0.7 tot 1.1 Msol), I think that is a relatively modest factor, in comparison with the overwhelming impact of orbital distance (AU), as Fig. 2 also shows clearly.

Please see my comment (Ronald January 20, 2020, 8:52) under the recent post:https://centauri-dreams.org/2020/01/13/orange-dwarfs-goldilocks-stars-for-life/What I have tried to do myself is to show the combined importance of the concept of CHZ ánd that of T-lock, by plotting both T-lock and T-CHZ (= residence time in the continuous HZ) for an earthlike planet against stellar Teff (and all other factors, such as initial rotation rate and eccentricity equal). Ok, maybe it would have been better to use stellar luminosity instead of Teff, but Teff is a rather good proxy, because it correlates to the 4th power with luminosity. I have the T-CHZ from table 2 in the cites paper “About Exobiology: The Case for Dwarf K stars” by Cuntz and Guinan. And I based T-lock upon their baseline in chapter 4: that T-lock for a planet in de CHZ of a star with Teff of 4800 K (about K3) is 4.5 gy, and working from there, given the fact that T-lock correlates with the 6th (!) power of orbital distance.

What we see is that T-CHZ and T-lock are correlated with Teff (and hence stellar luminosity) in sort of opposite ways:The result is a large ‘X’ shaped graph, in which T-lock is going from low to high with increasing Teff, and T-CHZ going from high to low with increasing Teff.

Since both tidal locking and leaving the CHZ are detrimental to higher (= complex multi-celled) life, I consider both as absolutely limiting factors. So a planet would have to be underneath both lines in the graph, in order to be habitable for higher life. Hence, only the bottom section of the 4 sections of the X is habitable (for higher life).

In this graph the optimal stellar Teff would be where T-lock and T-CHZ are the same: the intersection of the 2 lines which is also the highest point of the bottom section. Here both T’s are at their combined maximum. I think that optimum lies somewhere around 5200 K, or about K0, where T-lock and T-CHZ are both around 20 gy.

Ok, the exact numbers may have to be amended, but I hope the principle idea is clear. Again, I did not consider different initital rotation rates, eccentricity, axial tilt, moons etc., just assuming an earth analogue.(I could sent the graph to Paul for your review and critique).