When one of our Voyagers experiences a blip of any kind, it gets my attention. It’s not like we have any other options outside the heliosphere right now.

Both Voyagers have fault protection software that allows the spacecraft to protect themselves if problematic situations occur. And a problem did indeed surface aboard Voyager 2 on January 25, when there seems to have been a delay in the onboard execution of commands for a scheduled maneuver. The latter was a 360 degree rotation to be executed as a way of calibrating the craft’s magnetic field instrument, and the result of the delay was that two systems that consume power at relatively high levels were operating at the same time.

Not a good idea. Right now, with power dwindling inexorably, the Voyager missions are both dominated by power management. Hence the shutdown of Voyager 2’s science instruments to make up for the power deficit, as reported by the Voyager team on Twitter:

Here's the skinny: My twin went to do a roll to calibrate the onboard magnetometer, overdrew power and tripped software designed to automatically protect the spacecraft.

Voyager 2's power state is good and instruments are back on. Resuming science soon. https://t.co/4buDM32bap pic.twitter.com/4T856Lpxjm

— NASA Voyager (@NASAVoyager) January 29, 2020

The Voyager team was able to turn off one of the high power systems on January 28, and has now turned the science instruments back on, although data acquisition has not resumed yet. What’s needed is a review of spacecraft status as a check to ensure that returning to normal operations is warranted. What I want to focus on here is the distance this diagnostic work is being conducted at, about 18.5 billion kilometers. Bear in mind that one way communications require 17 hours, with another 17 hours for the response.

Thus 34 hours are required between sending a command and finding out whether it has had the desired effect on the spacecraft. We’re dealing with 1970s technology here, a fact that emphasizes the role that spacecraft autonomy will increasingly play as we push into the immediate interstellar neighborhood, when such operations will need to be handled aboard the spacecraft from start to finish. It’s a tribute to the quality of the Voyager design that we are still able to make the craft function given communications delays that were never anticipated.

We’re also working with two spacecraft whose power supply is heading for exhaustion. The radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) that powers up the Voyagers turns heat from radioactive decay into electricity, but such decay reduces Voyager 2’s power budget by about 4 watts per year. We’ve looked before in these pages at the balancing act this requires of controllers, who last year turned off the primary heater for the Voyager 2 cosmic ray subsystem to compensate for the decrease in power, although the instrument is still in operation.

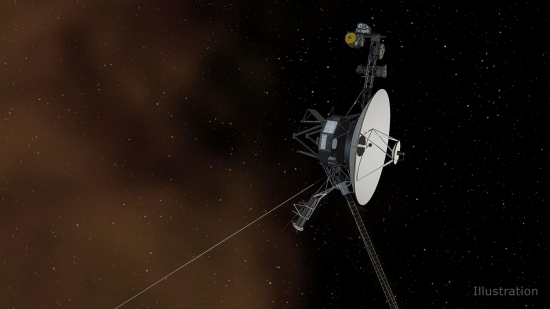

Image: This artist’s concept depicts NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft entering interstellar space, or the space between stars. Interstellar space is dominated by the plasma, or ionized gas, that was ejected by the death of nearby giant stars millions of years ago. The environment inside our solar bubble is dominated by the plasma exhausted by our Sun, known as the solar wind. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Imagine trying to keep all these balls in the air at the same time, and then factor in the need to manage the temperature of the various systems, which can be manipulated through heaters or excess heat from the various instruments and systems onboard. The critical computer system, radio transmitter and receiver electronics and other instruments would quickly cool to mere tens of degrees above absolute zero without heat management, and now, with the interplay of instruments being shut down, power savings have to be weighed against temperature.

We’re in what NASA calls the Voyager Interstellar Mission, and we have scant time remaining, despite the heroic efforts of controllers, to continue receiving data before the science instruments have to be turned off in their entirety. But for now our first interstellar craft, even if not remotely designed for that purpose, are still communicating and capable of sending data.

Keeping Voyager alive is a tale worth telling and will one day produce a book of its own. For now, though, I recommend Jim Bell’s The Interstellar Age and Stephen Pyne’s Voyager: Seeking Newer Worlds in the Third Great Age of Discovery. Bell slants more toward science and engineering, while Pyne opts for context and philosophy. Someone in the Voyager interstellar team is bound to produce the next book, which will doubtless become a testament to making missions achieve the seemingly impossible.

The Voyagers are an amazing story. The distances involved are staggering now. 17 hours each way at the speed of light! This is just a small taste of what a trip to a nearby star (as with Starshot) will be like. Upon arrival at Alpha Proxima the travel time for messages is 4.2 years! Obviously as you say Paul the key to success is a fully autonomous system that is also fully redundant. The engineering problems to overcome are enormous but well worth the cost and effort (I hope). Here’s hoping more funding for Starshot can be found as its initial funding dwindles.

I like explaining to folks at astronomy outreaches about the size of our solar system compared to light-years. I start with the AU, get up to Voyager 1 at ~150AU, traveling 38Kmph, then mention next solar system, Centauri, with 3 stars, etc., is 4+LY away. Then point out that there are about 63,000AU in one LY, so at V1 speed, we might get there in 60K years! “There is no Planet B, protect the spaceship you live on!” At least for the my foreseeable future.

Hello TT.

Yes most don’t realise what extreme distances we’re dealing with.

I ended up in such a discussion at the beginning of this January.

I were outdoors in the evening with one acquaintance at night time and had to explain that even though we see stars as clearly as Venus in the evening sky. But the planet is nearly in our lap, while the stars are incredibly far away and only seen as they are incredibly bright (while our Sun would not be seen at all at any larger distance.)

So yes the common view, and this was both an intelligent and in other ways well informed person – except for astronomical distances.

I added the mind bogging fact that one quasar actually can be seen even with a rather small telescope, or perhaps even binoculars and the light from that object is older than Earth have existed. At which point he capitulated to the idea of things that can be seen is far away indeed. =)

I agree even if we had found a suitable planet, and had the means to send a craft there. 99,9 (add nines for your best estimate) ….of humanity would not be able to migrate anyway.

So we really need to take better care of ‘spaceship Earth’ and starting today if any of the dreams we talk about here is to come true in the future.

Have to disagree with both of you guys.

If we never colonize worlds beyond this solar system, all life and all intelligent life in the universe will be destroyed when the Sun increases in size. And there are other apocalyptic scenarios that could occur, such as nuclear war or the Earth being impacted by another celestial object.

We are the steward of the Earth. Because we are the only intelligent species ever to evolve on this planet. As far as we know, we are the only intelligent species in the universe and lofe exists only on Earth.

This gives us certain miral responsibilities. We have to continue to reproduce (we can’t go extinct by attrition), we have to take care of this planet and we have to colonize space and spread life on Earth to other places.

Even if we can only get to 10% the speed of light in a manned spacecraft — which a fission fragment rocket, or even a NTR with sufficient fuel should be able to do — that is still good enough to get to the Earth-like planet orbiting proxima centauri. Especially if we can perfect the engineering of placing humans in stasis so they can sleep through long duration missions. There’s research going on for that as I type…

https://www.nasa.gov/content/torpor-inducing-transfer-habitat-for-human-stasis-to-mars

So yes, not only can we both colonize space and take care of Earth, but we are obligated to do so.

Well said tt. Climate change is an existential crisis. Work to remove politicians who deny climate change. Many governments have been captured by the giant oil and gas companies. Close to home for me, the Province of Alberta has been captured by the oil industry and fights all attempts to reduce carbon emissions in Canada. I believe the same is true in the U.S., starting at the top and moving through various state governments. If we don’t solve this problem we won’t have to worry about attempting to send probes to other stars. We’ll be busy trying to survive our own empty headed mistakes here on Earth. An interesting source of climate change information is available through the major insurance industries which underwrite insurances coverage for losses due to extreme weather. Take a look at the steady increase in real incurred losses corrected for inflation over the last 20 or 30 years due to climate change. Nature doesn’t care that we don’t want to make changes to our methods of generating energy. We will answer for our mistakes if nothing is done. We have about 10 years to make the massive changes required.

Definitely we need space nuclear reactors ASAP. And if we could develop a small breeding reactor, it would be even better!

I see no reason why we have to colonize any other planet, in our system or another. Nothing says we must survive as a species. Others have gone extinct, and we don’t particularly mourn for them. Maybe extinction and turnover of the leading species is indeed the natural order of things. We are evolving in some respects, but perhaps not fast enough to overcome our deficiencies. Our general greed and self interest will likely prevent us from accomplishing colonizing any other place, in a timely fashion. We see it already in our slow response to climate change, unwillingness to take the really uncomfortable steps to address it because we tend to deny that which hurts us in the short term.

As with others of our species, I tend to agree that mind is the most valuable thing we possess. Coupled with our physical abilities, we are the only species able to understand the universe that far surpasses any other species on Earth over the last 3+ billion years. If we went extinct, there is no certainty that another species will develop the mind as we have and the capabilities that have come from it.

But as I have suggested before, it may be that our fabricated machine descendants will be the embodiment of mind that colonizes the stars, not we biological creatures. Machine minds would be an acceptable legacy for me should [post]humans as a species eventually go extinct.

Don’t forget this wonderful documentary from 2017 on the twin Voyager deep space probes and that little golden disc they each carry for future finders, whoever or whatever they may be…

https://centauri-dreams.org/2018/10/12/the-farthest-voyager-in-space/

The Pale Blue Dot image taken by Voyager 1 is thirty years old today:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/02/nasa-pale-blue-dot-voyager/606529/

To quote:

Looking at this distant view of Earth, I feel the same way I do when I watch astronauts spacewalk outside of the International Space Station on NASA’s livestreams. The camera quality is grainy, the sound is staticky, and astronauts rattle off indecipherable jargon in serious voices. It is, if you watch seven straight hours of it, pretty boring.

But when you consider what the astronauts are really doing—not the slow and meticulous work of turning bolts and replacing batteries—the experience becomes something else. Human beings figured out how to build a home for themselves in the cold vacuum of space, filled with everything they need to survive, from breathable air to streaming TV and snacks, and now they’re dangling off the side of the whole thing as it travels at 17,000 miles per hour, and the only thing keeping them from floating into oblivion is a couple of fabric tethers. It is extraordinary. “Pale Blue Dot” is remarkable in a similar way—a display, however fuzzy, of humankind’s capacity to catapult away from our planet in an attempt to understand everything else.