330 light years from the Sun is the infant planet 2MASS 1155-7919 b, recently discovered in Gaia data by a team from the Rochester Institute of Technology. It’s a useful world to have in our catalog because we have no newborn massive planet closer to Earth than this one. Circling a star in the Epsilon Chamaeleontis Association, 2MASS 1155-7919 b is thought to be no more than 5 million years old, orbiting its host at roughly 600 times the Earth/Sun distance. A stellar association like Epsilon Chamaeleontis is a loose cluster, with stars that have a common origin but are no longer gravitationally bound as they move in rough proximity through space.

RIT graduate student Annie Dickson-Vandervelde is lead author on the discovery paper:

“The dim, cool object we found is very young and only 10 times the mass of Jupiter, which means we are likely looking at an infant planet, perhaps still in the midst of formation. Though lots of other planets have been discovered through the Kepler mission and other missions like it, almost all of those are ‘old’ planets. This is also only the fourth or fifth example of a giant planet so far from its ‘parent’ star, and theorists are struggling to explain how they formed or ended up there.”

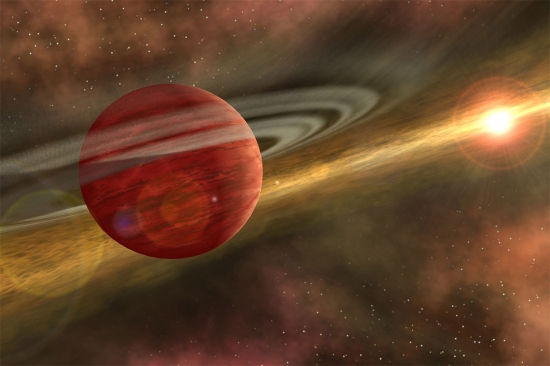

Image: Artist’s conception of a massive planet orbiting a cool, young star. In the case of the system discovered by RIT astronomers, the planet is 10 times more massive than Jupiter, and the orbit of the planet around its host star is nearly 600 times that of Earth around the sun. NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC-Caltech).

So a star a thousand times younger than the Sun has produced a giant planet far enough from its star to challenge our models of gas giant formation. But is it actually a planet?

From the paper:

The origins of systems involving such wide-separation substellar objects are presently the subject of vigorous debate (Rodet et al. 2019, and references therein). Given that 2MASS 1155-7919 b is quite possibly the youngest massive planet within ~100 pc—i.e., closer to Earth than the aforementioned massive young planets, as well as nearby star-forming clouds—this object is richly deserving of followup spectroscopy and imaging aimed at confirming its spectral type, age, and luminosity, in order to better understand its nature and origin.

Despite its unusual interest, the paper also reminds us, 2MASS J1155-7919 b joins other systems with wide separation, such worlds as HD 106906 b, 1RXS 1609 b, CT Cha b, and DENIS1538-1038. The fact that the latter two are thought to be brown dwarf candidates highlights the idea that such objects may form like low-mass stars, although the physical processes at work in their accretion and development are poorly understood. Here I’m going to switch to a different paper, this one on DENIS1538?1038 (Nguyen-Thanh et al., citation below).

Our discovery of the 1-Myr old BD [brown dwarf] that exhibits sporadic accretion with low accretion rates supports a possible scenario for BD formation…where low-mass accretion rates at very early stages (possibly with high outlfow mass-loss rate-to-mass-accretion-rate ratios) prevent VLM [very low mass] cores from accreting enough gas to become stars, and thus these cores would end up as BDs.

The authors of the 2MASS J1155-7919 b discovery paper point out that their putative gas giant is only slightly below the boundary between brown dwarfs and massive planets, making the above brown dwarf formation scenario a possibility. In either case, we have much to learn about widely separated objects in the same system when we find them this early in their evolution. The intellectual ferment in this area is exciting to watch.

The paper is Dickson-Vandervelde et al., “Identification of the Youngest Known Substellar Object within ~100 pc,” Research Notes of the AAS Vol. 4, No. 2 (7 February 2020). Full text. The Nguyen-Thanh et al paper is “Sporadic and intense accretion in a 1 Myr-old brown dwarf candidate,” in process at Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).

Since this large gas giant or almost brown dwarf is 600 AU, it might be not large enough or too far away from it’s host start to not effect the forming of a protoplanetary disk of gas and dust i.e. grab all the angular momentum need for inner planets to be made. It would be interesting to know if the host star has planets and how many of them.

That’s true, this object should not affect planetary formation to any significant degree at all.

A close look at the object could reveal what label it should have, if they take into account that also failed Brown dwarfs burn a bit of deuterium in the core at a young age – even Jupiter might have done so.

Paul Gilster: FYI(i.e. no need to RSVP). Back in August of last year, one of your posts concerned the Extreme Solar Systems meeting. An intreguing discovery coming out of that meeting was decametric radio emmission coming from a QUIESCENT rede dwarf star, for which the presenters favored star-planet interaction as the most likely cause. At that time, I “filed that one away” as particularly strong auroral emission coming from a very fast rotating gas giant planet(certainly interesting, but not earth-shaking news). Now the details have finally come out. “Coherent radio emission from a quiescent red dwarf of star-planet interaction.” by H. K. Vendantham et al. BOY WAS I WRONG! Apparently the authors have ELIMINATED any chance of it being a gas giant planet, and instead, insist that it must be a tidally locked Earth-sized planet in a 1-5 day period! The star’s designation is GJ 1151, which is located just 26.22 light years away. Now, here’s where it gets REALLY INTERESTING! GJ 1151 is of spectral type M7, meaning it must be VERY OLD(like TRAPPIST-1)to be quiescent. If the planet is in a 5 day orbital period, that would put it in the inner edge of the habitable zone, possibly indicating that similar planets like TRAPPIST-1 d may also have strong magnetospheres that would protect them their host star’s stellar wind. Finally, the presence of this planet can be confirmed with existing technology(i.e. Carmines and SPIRou)within a reasonable period of time. Stay tuned for further news.

“Is Proxima Centauri b habitable? A study of atmospheric loss.” by Chuanfei Dong, Manasvi Lingam, Yingiuan Ma, Ofer Cohen. Apparently Proxima b has a one in four chance of being habitable, which is A LOT HIGHER PERCENTAGE than I would have thought. Even more important, Lingam has distanced himself from Loeb in the latter’s EXTREMELY PESSIMISTIC VIEW of habitability of ANY planet orbiting an M dwarf star.

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters paper currently up on the exoplanet.eu website: The UV surface habitability of Proxima b: first experiments revealing probable life survival to stellar flares.” by X C Abrevaya, M Letzinger, O J Oprezzo, P Odert, M R Patel, G J M Luna, A F Forte-Giacobone, A Hanslmeier. SO: In the one in four chance that Proxima B DOES have an atmosphere, HMMMMM!!!!! Send Tardigrades FIRST! If they survive,I WILL FOLLOW!