It’s not a Triton, or even a Neptune orbiter, but Trident is still an exciting mission, a Triton flyby that would take a close look at the active resurfacing going on on this remarkable moon. Trident has recently been selected by NASA’s Discovery Program as one of four science investigations that will lead to one to two missions being chosen at the end of the study for development and launch in the 2020s.

These are nine-month studies, and they include, speaking of young and constantly changing surfaces, the Io Volcanic Observer (IVO). The other two missions are the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy (VERITAS) mission, and DAVINCI+ (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Plus).

Each of these studies will receive $3 million to bring its concepts to fruition, concluding with a Concept Study Report, at which point we’ll get word on the one or two that have made it to further development and flight. The NASA Discovery program has been in place since 1992, dedicated to supporting smaller missions with lower cost and shorter development times than the larger flagship missions. That these missions can have serious clout is obvious from some of the past selections: Kepler, Dawn, Deep Impact, MESSENGER, Stardust and NEAR.

Active missions at the moment include Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and InSight, but we leave the inner system with Lucy, a Discovery mission visiting a main belt asteroid as well as six Jupiter trojans, and Psyche, which will explore the unusual metal asteroid 16 Psyche. Discovery missions set a $500 million cost-cap excluding launch vehicle operations, data analysis or partner contributions. The next step up in size is New Frontiers, now with a $1 billion cost-cap — here we can mention New Horizons, OSIRIS-REx and Juno as well as Dragonfly.

I assume that New Horizons’ success at Pluto/Charon helped Trident along, showing how much good science can be collected from a flyby. Triton makes for a target of high interest because of its atmosphere and erupting plumes, along with the potential for an interior ocean. The goal of Trident is to characterize the processes at work while mapping a large swath of Triton and learning whether in fact the putative ocean beneath the surface exists. A mid-2020s launch takes advantage of a rare and efficient gravity assist alignment to make the mission feasible. Louise Prockter, director of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, is principal investigator.

Image: Dr. Louise Prockter, program director for the Universities Space Research Association, as well as director of the Lunar and Planetary Institute, is now principal investigator for Trident. Credit: USRA.

We can thank Voyager 2 for providing our only close-up images of Triton, which was revealed to be a place where explosive venting blows dark material from beneath the ice into the air, material which falls back onto the surface to create new features. The terrain is varied and notable for the striking ‘cantaloupe’ pattern covering large areas. With its distinctive retrograde rotation, orbiting opposite to Neptune’s rotation, and high inclination orbit, Triton may well be an object captured from the Kuiper Belt, in an orbit where tidal forces likely lead to interior heating that could maintain an ocean. What we learn here could inform our understanding not just of KBOs, but also giant moons like Titan and Europa, and smaller ocean worlds like Enceladus.

This would be a flyby with abundant opportunities for data collection, as this precis from the 2019 Lunar and Planetary Science Conference makes clear:

An active-redundant operational sequence ensures unique observations during an eclipse of Triton – and another of Neptune itself – and includes redundant data collection throughout the flyby… High-resolution imaging and broad-spectrum IR imaging spectroscopy, together with high-capacity onboard storage, allow near-full-body mapping over the course of one Triton orbit… Trident passes through Triton’s thin atmosphere, within 500 km of the surface, sampling its ionosphere with a plasma spectrometer and performing magnetic induction measurements to verify the existence of an extant ocean. Trident’s passage through a total eclipse allows observations through two atmospheric radio occultations for mapping electron and neutral atmospheric density, Neptune-shine illuminated eclipse imaging for change detection since the 1989 Voyager 2 flyby, and high-phase angle atmospheric imaging for mapping haze layers and plumes.

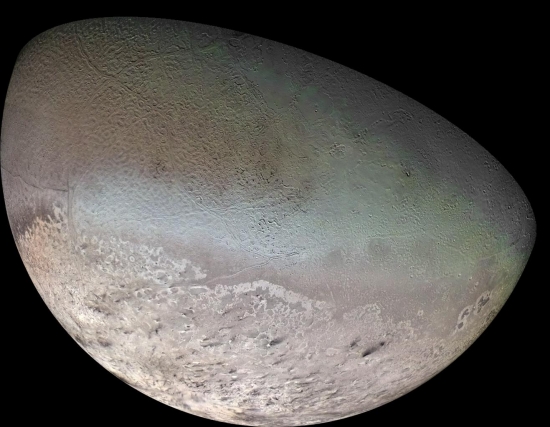

Image: Global color mosaic of Triton, taken in 1989 by Voyager 2 during its flyby of the Neptune system. Color was synthesized by combining high-resolution images taken through orange, violet, and ultraviolet filters; these images were displayed as red, green, and blue images and combined to create this color version. With a radius of 1,350 kilometers (839 mi), about 22% smaller than Earth’s moon, Triton is by far the largest satellite of Neptune. It is one of only three objects in the Solar System known to have a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere (the others are Earth and Saturn’s giant moon, Titan). Triton has the coldest surface known anywhere in the Solar System (38 K, about -391 degrees Fahrenheit); it is so cold that most of Triton’s nitrogen is condensed as frost, making it the only satellite in the Solar System known to have a surface made mainly of nitrogen ice. The pinkish deposits constitute a vast south polar cap believed to contain methane ice, which would have reacted under sunlight to form pink or red compounds. The dark streaks overlying these pink ices are believed to be an icy and perhaps carbonaceous dust deposited from huge geyser-like plumes, some of which were found to be active during the Voyager 2 flyby. The bluish-green band visible in this image extends all the way around Triton near the equator; it may consist of relatively fresh nitrogen frost deposits. The greenish areas includes what is called the cantaloupe terrain, whose origin is unknown, and a set of “cryovolcanic” landscapes apparently produced by icy-cold liquids (now frozen) erupted from Triton’s interior.

Credit: NASA/JPL/USGS.

If it flies, Trident would launch in 2026 and reach Triton in 2038, using gravity assists at Venus, the Earth and, finally, Jupiter for a final course deflection toward Neptune. The current thinking is to bring the spacecraft, which will weigh about twice New Horizons’ 478 kg, within 500 kilometers of Triton, a close pass indeed compared to New Horizons’ 12,500 kilometer pass by Pluto. This is indeed close enough for the spacecraft to sample Triton’s ionosphere and conduct the needed magnetic induction measurements to confirm or refute the existence of its ocean. As this mission firms up, we’ll be keeping a close eye on its prospects in the outer system. Remember, too, the 2017 workshop in Houston examining a possible Pluto orbiter, still a long way from being anything more than a concept, but interesting enough to make the pulse race.

My friend Ashley Baldwin, who sent along some good references re Trident, also noted that Trident’s trajectory is such that the gravity assist around Jupiter could, at 1.24 Jupiter radii, provide a close flyby of Io. Interesting in terms of the competing Io Volcanic Observer entry.

Could Trident do heliopause science? Is it equipped with a RTG?

Power via multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG); I don’t know what heliopause science might be possible here, but we’ll learn more.

Not as much as New Horizons or the Voyagers.

Firstly because of the limited amount of propellant on board ( to save on mass and cost ) . But also because of the reduced long term efficiency of its powering MMRTG versus the conventional RTGs of the other probes. Plutonium 238 may be the fuel source of all US RTGs – with a long half life of 84 years – but it supplies energy via converting heat of radiation to electrical power. This via a thermocouple ( a combination of metals with varying conductive properties ) . The efficiency of this is generally only around 20 % – making it the major limiting factor on the performance of any RTG . MMRTGs have a greater starting efficiently than older types of RTG , but at the cost of reduced durability. Limiting operations to perhaps 14 years .

So not much longer than the Trident 12 year transit time. But this time can be put to good in “trickle charging” ( and heating ) powerful on board batteries to cover the power requirements of the relatively short encounters at Triton/ Neptune and hopefully Io too. Trident, if it flies, will deliver most its science enroute to and also at its target rather than afterwards.

It’s a pity to hear that. It’s paramount to know more about the ISM before launching really interstellar probes.

Triton has been a favorite destination for me now that Titan is not quite so mysterious. I do have one small quibble. Efficiency of electricity production via thermocouples tend to be well under 10%. As noted, the reliability and low weight make them preferable for deep space probes. Work in heat engines (variation of the Brayton or gas turbine cycle) for space applications could raise efficiency to over 20% but as far as I know, no such units have been launched. The problem seems mostly related to heat rejection.

@Patient Observer:

Do you refer to ASRG? Its development was plagued by cost overruns and delays, like SLS and JWST, until it was put into pseudo cancellation. It seems that NASA can’t develop new technologies anymore within a reasonable cost and schedule.

I am not familiar with ASRG but have come across various articles about nuclear and solar power systems based on a gas turbine cycle. Heat rejection schemes included various flat plates arrangements as well as direct exposure of heat-transfer fluid droplets to the vacuum of space (lots of surface area and minimal weight).

Triton is my almost very, very favorite planetary object in the solar system next to the moon. I suppose I feel that way because it appears to have the only body in the solar system with lakes, or pools of liquids on its surface, that was placed there naturally. Even if they are liquids of ethane and natural gas (just don’t tell Saudi Arabia about it).

Mr. Gilster -would you happen to have a personal source that might be able to tell you if anyone is thinking about using this particular mission to actually switch over from flyby to perhaps an orbital one? The reason for my asking is that in the sci-fi book “Aurora” there was chapter or two near the end of the book in which the returning interstellar voyages used many, many multiple gravity assist to slow themselves down in the solar system, such that they could finally be captured by the sun.

Could any of your sources possibly know or be aware of possible plans, now or in the future, which would permit multiple gravity assists (and/or aero breaking maneuvers) in the Neptunian system that could permit ultimate capture by Neptune or Titan ?

By the by, just as an aside, they say they’ve identified for the first time molecular oxygen in a planetary system in another star system.

No plans to make this mission into an orbiter. As to gravitational assist maneuvers around Neptune and Triton, I know of no such plans and no idea re feasibility, but maybe some of the readers have thoughts on aerobraking at Neptune, etc.

I am not sure how much of Pu238 is reqd for a flyby vs. an orbiter.. Seems like Pu238 is the limiting factor. If one is going so far, might as well do an orbiter mission which is in line w/NASA philosophy of flyby, orbiter and then lander. This would hence negate qualify for a low cost Discovery mission.

Areobraking is simple.. just follow the Pluto Orbiter proposed plan for aerobraking. Maybe even for orbiting Triton and other Neptune’s moons, the PLorbiter strategy may work. I say, its time to go for an orbiter instead of a flyby..

Any plans for an extended mission (once past Triton)?.. At twice the wt of New Horizons I hope Trident will have faster data downlinking abilities. My final wish, is for Trident to carry a Huygens kinda lander/hopper to image at ground level an active cryovolcano. That can be more easily w/an orbiter.

I think aerocapture ( related but not the same as aero braking ) is what you mean. For a probe on a hyperbolic trajectory to Neptune, it would have just one shot at slowing enough in the atmosphere to achieve orbit. This would require detailed knowledge of Neptune’s atmosphere – especially its density over time . Knowledge that just isn’t available from either Voyager or ground based observation. Given the high closing speed, the probe would have to lose just enough delta-v to avoid de-orbiting and burning up or bouncing off the atmosphere and off into the oblivion of deep space.

Ironically if the pre-formulation work allows Neptune observation as part of the Trident mission profile, the atmospheric data collected might support a future aerocapture utilising orbiter . Which with a large launcher and Jupiter gravity assist would combine to reduce transit times massively.

After all the gravity assists and the coast/hibernation phase, using a Ion propulsion (like Dawn’s) system about 26~27 AUs away from Triton for 2+ years in Reverse mode would slow the spacecraft for capture (for an orbiter) or slow it down while the “encounter” phase begins. Again in a Discovery mission budget hence weight constraint, one wonders, if such a config will be possible. Its in end about packing in max instruments (within the budget) vs. its wt vs. slowing the “encounter” spacecraft speed for better data. Using the fastest rocket available at launch (whose cost is outside the Discovery budget) would be key. Sorta plan the Pluto orbiter proposal mentions along w/a Charon gravity capture (like Cassini).. I mention all this as NASA may not send an orbiter for a long time IF the flyby mission happens.. Hence my case for an orbiter instead of a flyby and have it NOT a Discovery mission..

Solar electric propulsion, “SEP” staging- i.e using an ion drive to act as an additional staging rocket for an extended initial period of a probe’s journey to the outer solar system ( specifically Saturn ) has been extensively researched by Nasa Glenn. For over a decade. Most recently combining the largest iteration of an Atlas V EELV with the newly matured “NEXT”, next generation ion drive . A big improvement on Dawn’s system.

NEXT ion drives where even included as additional , free, ” government funded technology”,GFE for the last New Frontiers round. But despite a Saturn mission – Dragonfly – being selected, SEP staging was not considered despite the availability of NEXT. Or even a smaller solar array to power instruments – with an MMRTG used instead. The Enceladus Life finder, ELF concept did propose utilising solar power – just for its instruments – and wasn’t even short listed despite a powerful science case.

So the combination of technology required obviously wasn’t considered reliable enough by the Nasa assessors. As ELF showed there are solar arrays available that should theoretically operate as far out as Saturn’s 9 AU ( 1/80 the solar flux of Earth !) . Though providing a just a few hundred watts to power science instruments is a long way short of the 25 giga watts required for an ion drive.

Remember that New Frontiers and Discovery programmes have tight budgets with little or no availability for technological development if there is to be a meaningful science payload. That’s their purpose and that’s why they use older but proven technology. Its thus a huge testament to the ingenuity and skill of the IVO and Trident teams that they have got such capable concepts short listed within budget.

As I understand it, the weak point with even modern, ultra efficient solar arrays is that their performance and integration to power an ion drive is very difficult – especially in the cold and dim environs heading out from Mars. ( all solar array performance drops off alarmingly in ” LILT” – low intensity, low temperature – conditions. )

But we will probably see SEP staging, before aerocapture, for the next flagship missions to the outer solar system after Clipper. Glenn’s research showed that combining an Atlas V with three NEXT SEP drives for staging , could deliver a four tonne payload to Saturn in just over 5 years ! Presumably a block 2 SLS would reduce that even more and open up Uranus at the least.

gigawatts? Very “Back to the Future”. Don’t you mean kilowatts? Even VASIMR only uses megawatts at full power for a hypothetical fast Mars flight.

Typo. Should read KiloWatts. No GigaWatts though “Mega Watt” arrays a possibility. Ultimately someone is going to have to design and build a compact spaceborne reactor though . There are much more potent hydrogen based ion drives than VASIMR both in terms of ISP and thrust. Nuclear electric will power taut sort of perfomance for targets like the Kuiper belt and possibly even the Oort Cloud. Interstellar still out of reach down that technological pathway sadly.

Isn’t this because such probes are “dumb” and must be controlled precisely and accurately from mission control? If it was “smart”, able to “pilot” itself to adjust its trajectory through the atmosphere dynamically to reach the desired orbit using aerocapture, this need for detailed advance knowledge could be [mostly] avoided. A possible domain for study and training an AI to navigate the craft in this situation.

Aerobrake timing is critical. At that speed you may have less than a minute to apply a large thrust to correct for unexpected friction (or lack of it). Only a chemical rocket can do that and even that may not be enough. Only when that challenge is met can an onboard guidance system (AI or not) succeed.

From my youth I recall the nail biting at NASA when the first Apollo missions coming inward from the Moon hit the atmosphere. That aerobraking maneuver had little margin for error (and no propulsion option). And that’s Earth whose upper atmosphere was reasonably well understood at the time.

Ashley Baldwin

“The reason for my asking is that in the sci-fi book “Aurora” there was chapter or two near the end of the book in which the returning interstellar voyages used many, many multiple gravity assist to slow themselves down in the solar system, such that they could finally be captured by the sun.”

My initial question REALLY didn’t have to do with any kind of atmospheric breaking (although, come to think of it, it might have some use in what I was proposing), my knowledge of the Neptunian system was with regards to any moons of the planet and directed to the idea that you use multiple close passes to the moons to achieve slowing gravity assists to permit ultimate gravitational capture.

Producing multiple gravity assists with the intention of slowing the probe in each successive maneuver and using that as an objective to ultimately permit capture by the Neptune planetary system was the ultimate goal in my asking my original question as outlined in the double quotes above. I assume for arguments sake that if there are multiple moons of Neptune AND these moons have essentially no atmospheres that it would be conceivable that you could dip real, real, real close to their surfaces (ignoring for the moment the topography possibilities of constraint) and get within perhaps one-mile of the surface of the moon to really, really enhance up your gravity assist to the Max. That’s where I was going with my original question…

Charley – I liked the book Aurora too, but the idea of multiple planetary encounters, on a fast approach from outside the solar system, providing enough slowdown to keep the ship in the system, was pure fantasy and not even remotely possible. The same would hold for any reasonable flight-time to Neptune: the velocity would be way too high to allow deflections and slowing down among the moons of Neptune so that the probe stayed put in orbit there.

Aurora has received some withering criticism on that point. No way at these velocities.

jonW , Paul Gilster

I only use the ‘Aurora ‘ book as an example of the application of multiple gravity assists as a slowdown mechanism; my point being that perhaps a similar type of arrangement would work at Neptune using its moons.

It would be an interesting idea to explore at Neptune, but I would imagine some kind of Oberth maneuver at Neptune would have to be preceded by some other form of serious deceleration in the latter stages of the approach. But others would know far better than I how this might be put together. Maybe somebody can run the numbers on a hypothetical mission.

Paul Gilster,

I only like to add a little bit more commentary here because I think it’s good to put it in perspective. Obviously in the book “Aurora” they were coming off of a, as I remember it, a 20% lightspeed incoming flight. We have nothing like this with this Neptune probe; and if, as I think it might be, that the moons around Saturn are devoid of atmosphere, then that might permit flying very, very, very close to the surfaces of these moons, which would greatly intensify the gravity effect. Maybe yes, maybe no…

llustrating why aero capture is not easy at Neptune or likely in the foreseeable future . Comparison with other “easier” ( in as much as rocket science can be !) targets . Which means not for an orbiter in the next twenty years.

https://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?action=dlattach;topic=34127.0;attach=572939;image

Gravity assists , or gravity braking are ultimately drifen by gravity . From the larger space body to the spacecraft in this instance. Saturn’s gravity – and thus its gravitational escape velocity – is 35.6 km/s . By way of illustration , and perspective – in order to be captured by that planet from its hyperbolic transfer orbit , Cassini required a 96 MINUTES full burn of its propulsion system . In other words enough to lower its velocity relative to Saturn to below Saturn’s escape velocity and allow capture/orbital insertion. The engine burn achieved this. Just. In that time Cassini’s velocity was lowered by “just” 626 m/s . Or 2253 km per hour. So in other words it was largely Saturn’s gravity that captured Cassini with just a little help from the probe’s propulsion system. Cassini’s precapture velocity was about 36.6km/s – fairly representative of outer solar system craft that take years to reach their targets.

By way of comparison , Titan – the largest moon in the solar system- has a mass of about 1/3226 that of Saturn – with a escape velocity of puny 2.64 km/s . ( Triton’s escape velocity is just half of this ) So you can fly as close as you can get to it and any change in your velocity – up or down – ain’t going to amount much . Flybys in moon systems are mainly used for altering trajectory ( to another target ) rather than velocity.

Saturn receives just 1/92 the solar flux of Earth . So any solar powered probe is going have to have some seriously big and efficient solar arrays to work there. Tough, but not impossible and a stretch goal for NASA over the next decade. It’s moon Titan has a denser atmosphere than Earth , filled with an organic haze – which blocks out nearly all visible light. So any Titan lander ( like Dragonfly) will require a radioactive power source to operate.

In the book ‘Aurora’, at page 404, It tells that after decelerating through the use of 1) firing the main engine at some distance (Neptune orbit!), and 2) using magnetic braking during a close flyby of the sun and starting the main engine again close to perihelion through something resembling an Oberth manouver, the craft would enter the Jupiter system at about 0.3% lightspeed ~ 900 km/sec.

Triton (not to be confused with Titan) is _cold_ – its surface temperature is 38 K. This is less than half the melting point of propane (85 K), which oddly melts sooner than methane, ethane, or butane. There is “cryovolcanism” on Triton, which is to say, occasionally nitrogen occurs in gas form.

The solid nitrogen on the surface might eventually be of some interest to miners, since popular farming destinations like Mars and Venus are terribly short on the substance, and at 8% of Earth’s gravity this moon has an escape velocity just over Mach 1. It would be interesting to see a plan using orbital mirror arrays that could heat and refine the nitrogen from Triton’s surface rocks and recondense it into simple structures suitable for transport.

Sorry, I forgot a conversion in that last figure on escape velocity – it’s actually over Mach 4 (5229 km/h; confirmed using https://www.universeguide.com/planetmoon/triton … also, it’s an abuse of the Mach unit to refer to it in vacuum). Still plausible to achieve on the ground there, but much more impressive!

Magnetoshell aerocapture will be the technology that allows us to obtain orbit around planets and moons in the outer solar system. From what I can gather we’re still at least a decade away from employing it on a mission.

Though I personally like a Triton mission. If a mission would be decided on public interest alone, I think the Io volcanic observer would have a very good chance of capturing the imagination also outside of the circle who already have a firm interest in space science.

It is a wild unusual world.

Yet I prefer Triton/Trident, Voyager provided interesting hints, it’s just too bad that even the early planning at least would try to find a clever option to make it an orbiter.

That retrograde and inclined orbit might have the interior of this moon worked on like a dough, and an internal ocean is indeed likely.

Yes. I think Triton will prove to be another ocean world.

There are plenty of clever and more practical options for an orbiter. But not for less than $2 billion and certainly not for $400 million ! Just getting a meaningful probe there for that cost is nothing short of incredible. Let alone one as capable as Trident.

If it flies, Trident will give as much science per dollar return as just about any NASA planetary mission – ever. More so even than New Horizons as it will likely target both Triton and Neptune ( & Io ?) . Whilst possessing a significantly larger high gain antenna, HGA. Combining this with a far more potent on board computer to allow much greater data transmission. The big HGA being required to act as a heat shield during Venus flyby.

Hello Ashley. No it is no high odds on the bets for a wet interior. :)

And you are right, with that price tag it is good science for the money.

But for a flyby the science instruments are purpose built for the target world, to get as much as possible from a brief encounter.

Pretty images are nice, but while Io, Neptune and Triton are very different kinds of objects – the data for the two first will be limited to some degree.

I still favour Trident/Triton, since we only have tantalizing hints and practically is unexplored. But will not get disappointed of the Io volcanic observer wins out – it would provide even more science for the money. And that surface will get the attention of more than the space community – but god forbid also the conspiracy people who will see devils or something. ;)

Thanks Paul.

We won’t know about NASA’s priorities for flag ship orbiter missions to the Ice Giants until the annual Decedal report comes out – likely in a about a year’s time . The launch windows with Jupiter gravity assists are open for them both at and around the end of this decade. So things are going to have to happen quick if such a big project is to ready to fly by then.

The Outer Planets Advisory Group have done a lot of concept work on such missions and determined that they couldn’t be done meaningfully for less than $2 billion and probably nearer $3 for a top class effort. That’s still half of Cassini’s cost though thanks to the large amount of high heritage instrumentation coming out of Clipper, Juice, New Horizons , BepiColumbo and the various Mars missions. Transit times are around 10.5 yrs for Neptune and 8.5 for Uranus – a year or two less with the SLS Block 2.

With Clipper not likely to fly before 2025 at the absolute earliest we will have to wait to see whether a Mars Sample return mission edges out an Ice Giants effort in Decadel. If it does that rules out a flagship till at least the next window in the mid 2030s. You would think Uranus being nearer would help it edge the choice at whatever time .

I’m sure that’s why Trident’s team have proposed a very sophisticated, efficient and well though through Triton concept . And contributed to it being short listed . Good enough to go forward for pre formation work where it will be judged with its rivals on three areas ,

1/ science benefits (40%) ,

2/ scientific practicality (30%)

3/ operational / cost practicality ( 30%) .

NASA’s senior administration can judge purely on the scores here or make a decision based on their own judgement too. Such as the Venus science community withering due to a lack of in situ data. No guarantees – though I think just about everyone thinks Earth’s evil twin finally deserves a turn. Just a guess but Veritas could launch after Trident but arriving at its target in just 6 months and with the facility for significant extension could nicest keep us occupied while Trident travels .

Goodness me. Trident really is very clever. The science it will do on Triton alone is peerless. The pre formation work will also look at what it can do during its Venus and Jupiter ( Io especially ) encounters and of course Neptune itself . Shame to go all that way and ignore such ab inviting target. It has an unusually large instrument payload for a $500 million mission thanks to some shrewd savings. After launch it will follow a “ballistic ” trajectory – relying almost exclusively on gravity assists to reach its target . Thus negating the need for a complex and costly onboard propulsion system – with lots of propellant mass. Just a hundred or so Kgs of hydrazine for fine tuning its trajectory . In space mass=cost. It’s instruments are also all based (or indeed copies of ) flight proven technology – so no development costs. This round the Discovery programme will also provide operations costs outside of he main budget envelope – so will not penalise long missions such as Trident. One might even wonder whether this gives a clue as to NASA’s planetary science plans. Following on from this was the availability of up to two MMRTGs for power – obviously relevant to outer solar stem missions – and at the relatively low cost of $59 million. Not as efficient as the RTGs that powered New Horizons ( they are actually left over from the last New Frontiers round, as “Dragonfly” only needed one of the three made available ) . Especially over a twelve year transit time, but here again the Trident team have been clever. The spacecraft is provided with cheap but powerful batteries that are “trickle charged ” enroute whilst the craft is in hibernation before THEY, and not the MMRTG direct , will power any flyby science . Unlike New Horizons this will also provide enough to power ALL the instrument payload simultaneously if required – essential if the most is to be made of just a few hours of close encounter time. As with New Horizons data relation can occur over the months after encounter . ( I believe that New Horizons returned 8 Gigabites of data on Pluto and I’m sure Trident could

The twelve year transit time is not just slow for efficiency – it also takes advantage of a unique positioning of Triton and Neptune in 2038. Arriving during Neptune’s “summer” ( as with Voyager) to look for plume activity, if is indeed temperature related rather than cryovulcanism on an ocean world ( as is hoped and a core of the science proposal ) but also taking advantage of Triton eclipsing the sun after the spacecraft’s initial encounter , to allow imaging of BOTH sides of the moon.( >80 % total surface ) .

Although as stated a Neptune/Triton flyby mission has been done before , that was over thirty years ago with FIFTY year old technology. Basically an analogue TV attached to a fax machine. With tortoise like transmission rates . New Horizons has shown what modern flybys can now achieve – with near 20 years older technology too. With the more limited lifespan of Trident’s RTGs compared to New Horizons, as well as its small propellant load – I’m not sure it would go in to achieve the same impressive post primary mission science as its forbear. But it certainly has a lot of potential enroute . Io is very much under consideration given Trident’s flyby of Jupiter will take it interior to that moon’s orbit . If having travelled billions of miles over twelve years Trident can come within just 300 miles of its target then I’m sure it can do equally as well with Io and with a nit too dissimilar payload to Io Volcanic Observer – and with a 2032 ” halfway” encounter about the same time as proposed for IVO. The high transit velocity will mean only minimal exposure to the high radiation at this point.

It’s incredible really that all four short listed concepts involve pure planetary science for such a “low” budget – especially with two of the targets being in the outer solar system. Exciting times ahead.

I think a flyby is too frustrating. Years to wait for a few weeks’ worth of data about one face of the target. If we accept that an orbiter is not practical (for reasons of fuel mass or travel time), then one idea is send a bundle of probes (three?) that can disassemble with some having enough fuel to decelerating to different degrees so that they pass the target sequentially. With current rocket technology, that idea would need too much mass, but I think Triton would be a prime target for testing of Starchip tech, which could send dozens (hundreds?) of dumb probes for not much more than the cost of sending one. If they are traveling at 0.1c they would arrive at Neptune in only 42 h. If they arrive over a sufficient span, and even if each only captures a few images, Structure-from-Motion analysis can reconstruct a 3D model of the target to surprising precision (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structure_from_motion). So if I had any influence I would suggest that we wait a few decades (years?) for this job, and instead launch orbiters to Io or Venus.

A Neptune ( or even more so Uranus ) orbiter is entirely practical. NASA have explored perfectly reasonable concepts betwen $ 2-3 billion with a conventional Cassini archictecture . Much less in partnership with an enthusiastic ESA. Cheaper by far than Cassini.

With the use of SLS block 2 and its Exploratory cryogenic Upper Stage , EUS, even a Cassini sized ( six tonne) probe could get to Neptune in nine years for an extended in system tour . Quicker still with a solar electric power staging rocket for the first 3 AU or so of the journey.

However the push for a return to the Moon ( why ?) , the huge cost overrun on the JWST, the likely delay on Clipper launch due to AND in addition to the long SLS development time – all combined with a strong “Mars sample return” NASA lobby – threaten to push the Ice Giants ( entirely unfairly ) down the Decadel priority list. Again.

Hence the inclusion of Trident, which will still hugely improve knowledge of Triton and likely Neptune too despite being “just” a flyby. There will be plenty of other missions taking place whilst it’s on its long journey , that can keep us all occupied . ( including potentially, Io ) Trident gauantees the late 20s launch window isn’t wasted. If Trident flies and the Ice Giants aren’t prioritised in Decadel then it’s a lot better than nothing. If the Giants are prioritised then likely there will be a flagship to the Uranus system with its greater proximity and conveniently later launch window extending into the 30s.

Well, what about the elephant in the middle of our discussion???

SpaceX Starship could launch an orbiter to Triton with just the 1st stage and an upper 2nd stage for under 5 million $$$. Gigafactories will be producing 100’s of these megarockets in just a few years! The game changer has arrived, so what are the possibilities??? This is something that I would love to hear the opinions on just how much it will change the exploration landscape. My friends, Musk will get this working a lot quicker then any other megarockets and YOU may be travelling halfway around the world in less then an hour…

It looks like the stage is set for a very big change in the space industry, and particularly the launcher part of it. It is hard to say how it will look. And it will take some years to play out. I think most of us have a ‘wait and see’ attitude about it before beginning designing 50 ton space probes for outer solar system expeditions.

Good point, but it would be fun to look at the possibilities. Since SpaceX has had good luck with spacecraft development and mass production (Starlink), what about mass producing the buses for planet orbiters? Give them a contract of one billion to develop it and work with JPL to add the instruments for each mission. That and the cheap launcher would keep the price down and their design teams seem to be well ahead of everybody else. They could also make a rover lander, just pack the instruments in a Tesla Cybertruck with solar arrays or Radioisotope thermoelectric generator for the batteries and the autonomous pickup would do the rest. Wonder if it would work on Titan???

Point taken. I’d vote for that :)

Gigafactories will be producing 100’s of these megarockets in just a few years!

Why?

SpaceX in 2021 Will Have 3,000 Employees Mass-Producing Two Starships Per Week.

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2020/02/spacex-in-2021-will-have-3000-employees-mass-producing-two-starships-per-week.html

SpaceX Plans Starship Gigafactories to Introduce the Hypersonic Age.

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2020/02/spacex-plans-starship-gigafactories-to-introduce-the-hypersonic-age.html

You can hear Musk’s rationale for that here:

https://www.thespaceshow.com/show/11-feb-2020/broadcast-3459-dr.-robert-zubrin

Thank you both for the links. My job experience is management of engineering and manufacturing operations at a small and innovative company. With all due respect, Mr. Musk and Mr. Zubrin are selling dreams and hopes with his claims of hundreds of Starships flying to Mars with thousands of people at $300,000/head.

The reasons for skepticism are countless but lets start with a simple one. The Falcon 9 has been flying for a number of years and has demonstrated resuability of the first stage on a routine basis (truly impressive engineering). Were we not expecting a drastic reduction in launch costs (IIRC, $100’s/lb to LEO) by this time yet launch costs are not significantly lower (what, 20% – 30%?). FWIW, Russian launch services would be competitive with the Falcon 9.

https://advanced-television.com/2019/03/29/russia-to-cut-satellite-launch-costs/

(please no snarky comments, Russia has apparently the most stable and secure financial position of all major economies and has been rebuilding its technical base for years. They will likely be back in a big way in the coming years. And there are the Vulcan and the New Glenn efforts which seem more grounded in reality)

The Space X price to launch 4 tourists on a jaunt to LEO around 2022 has been cited at about $100 million (and sure to rise). What happened to the tourist flight to loop around the moon? When will we see a the game-changing reduction in launch costs?

By 2023, the skies should be crowed with Starships, right? Yet we have SpaceX trying to sell tourist seats to LEO for $20-30 million each.

I want to believe but I can’t.

Your wellcome.

Just to be precise, Zubrin is not selling it. He simply tells what he saw and what Musk said to him. Indeed, he has for some years pointed out some major flaws of Starship’s mission architecture to Mars. Some have been addressed by SpaceX, most did not.

Musk has mainly reduced launch prices compared to the bloated, inefficient big space companies in the US, not so much compared to Russia or China. It remains to be seen whether he can reduce them further as he says. And, more importantly, whether manned launches are as secure as Soyuz et al. After all, an accident was what killed the Concorde project, for example, and we have had no more supersonic passenger jets ever since. It could happen to SpX too. I’m not a Musk fanboy nor a Musk hater. Nor is Zubrin either. He is capable of the best (reusable rockets) and the worse (Hyperloop).

SpaceX main funding strategy for Starship is not space tourism. Indeed, they don’t seem to care for space tourism at all. All the tourism proposals came from outside SpX (the most recent one, from the same company that sent tourists to the ISS years ago). Their main plan for funding Starship is the Starlink megaconstellation.

Agreed on all points although I do wonder if Starlink can generate the cash flow to fund mass manufacture of Starships given the relatively small market size (users not able to access fiber), 5G implementation and the other LEO internet satellite providers.

I do remain highly skeptical that interplanetary space ships carrying a hundred people on multiyear journeys will cost far less to build than an Airbus 320.

I suppose that Musk sees the handwriting on the wall in his decision to phase out the Falcon 9 as its competitive edge will erode as the competition responds with their own solutions to reduce launch costs. That is a good thing, of course.

Trident and DAVINCI are going in the same direction to Venus pick these two for flight (1 launch vehicle )

Steal the TMAP and place it on TRIDENT for the Io flyby

The JIRAM infrared spectrometer on Juno took some spectacular images of Io’s volcanic surface during a relatively close pass of the moon ( 290000 miles) in Dec 17. There are plans for further images from close distances . JIRAM operates between 2-5 microns with the upper limit within the “thermal infrared ” required for “hot spot” imaging .

The infrared spectrometer on Trident operates at 5 microns so should provide better images during a close encounter with Io. Though over a smaller fraction of its surface area than IVO given just the one flyby. Though its observations could be combined with those of future JIRAM images to offer a significant degree of time series surface mapping as planned for IVO. The thermal imager on IVO is based upon the MERTIS infrared spectrometer on BepiColumbo which operates at between 7-14 microns wavelength and possibly longer. Like IVO Trident also possesses a wide and a narrow angle imager and magnetometer . Not be bespoke for Io of course , but a lot of cross over .

A little more about Triton, the noted target.

As the Voyagers approached Jupiter in March of 1979 in the journal Science there were published a couple of articles in anticipation of what would be seen there. One addressed surface hotspots and the other examined thetidal interactions of the four Galilean moons and Jupiter.

All four moons ‘ orbits were near circular, but when they passed each other the tugs on them in Jovian field was like plucking on tightly strung cords. Hence, after that inspiring observation, analysis and predictions ( volcanoes), one was wont to wonder where something like that could be done again in the solar system: Triton.

In my naivete’ , looking at Triton and Neptune, I had hopes that volcanoes would be found and wrote a note or two to that effect to Science prior to the Neptune passage of Voyager 2. The arguments then are still worth considering looking at possibilities for

Neptune and Triton science with a lower case s.

1.)Triton evidently is a captured satellite since it revolves around Neptune retrograde an inclined to the equator over twenty degrees.

2.) With Neptune’s high rotational rate and being a ball of gas or very fluid, its visage is oblate. It is spun out wider at its equator than along its pole.

3.) Triton like the Galilean satellites of Jupiter is in nearly circular orbit, almost to the limits of perception – but yet it is like a wheel at high speed and out of alignment.

If Neptune bulges at its equator it is is not a uniform gravity field. Like the Earth ( or even the Moon, Jupiter…), instead of having a simple inverse square field, modeling it requires a series of small perturbation terms. If the first term of a gravity model represents the inverse square effect, for the Earth is “unity”, the next big term representing the effect of its equatorial bulge is 1.08262..x E-3., or a thousand of the value. Neptune probably has terms of that magnitude, but it is also a lot more fluid than the Earth is. The earth’s gravity is based on a more rigid body than Neptune appears to be. For satellites of Neptune, the field with its perturbations is probably time varying. No big deal if you are off millions of miles away, but significant if you are orbiting up close and inclined to its equator.

So here ( well, really there) you have this big moon around a body larger than Earth criss-crossing its equator and stirring up tides in an atmosphere deeper than an ocean. And what do you know: Coincidence, the prevailing winds on Neptune at low latitudes are retrograde too, hundreds of kilometer per hour. Coincidence? There is a latitudinal distribution of velocity east to west on order of Triton’s.

Well, the winds were not known prior to the flyby, and the phenomena observed at Triton were not volcanoes, but geysers. A number of arguments have been presented for their existence far afield of tidal heating: nitrogen green house effects, dust devils. Prior to the New Horizons passage by Pluto, I would have thought tides being weaker at Pluto, there would have been a counter example settling whether the geysers at Triton were tidal or not, assuming Pluto was more of a static environment than Triton. Definitely not the case.

But the outer two gas giants, we look at as though through a blue filter.

There could be more to be told thanks to Neptune having Triton and the resulting tides.