Perhaps the most significant paper I have yet to read on the subject of habitable zones has emerged from the University of Oxford, with collateral help from the Lamb and Flag on nearby St. Giles St. (a stout place), along with two scientists who claim no affiliation other than ‘Earth.’ The paper defines the Really Habitable Zone, that region around a star within which acceptable gins and tonic are likely to be found. “We suggest that planets in the Really Habitable Zone be early targets for the JWST, because by the time that thing finally launches we’re all going to need a drink.” Which is so patently true that I can only nod with approval.

Adding that most habitable zone models now in play are defined by the need to justify the budget of the JWST to the US Congress, the authors proceed to note the difficulties in creating a habitable zone definition with which all astronomers can agree. What all astronomers can support, they argue, is a definition of what makes life worth living. Throw in a good infrastructure to support the distribution of limes and you are on your way.

The Really Habitable Zone (RHZ) defined here has a substantial history in the literature, as the authors note:

Astronomers have long been interested in alcohol. Shortly after the introduction of gin to the UK, Flamsteed made the first observations of Uranus but mistook it for a star; we suggest a connection between these two events. In the twentieth century, papers by Coburn (1932) and Phenix & Littell (1933) discuss the use of alcohols to treat photographic plates, though they remain silent on its use in treating astronomers. Ball et al. (1972) detected methanol, though this is – in space, as on Earth – clearly undrinkable. Luckily, Zuckerman et al. (1975) soon found ethanol.

The chain of reasoning is tight. The paper continues:

It is therefore clear that conditions which support the creation of decent beverages will also support astronomers, which is a working definition of civilization. The choice of gin and tonic is based on the work of Adams (Adams 1979), who hypothesised that a drink named something similar existed in 85% of civilizations.

Image: Much of the research for this paper was conducted at the Lamb and Flag in Oxford.

A Minimum Acceptable Gin and tonIC (MAGIC) is defined; here the authors do extol the value of citrus, but being British, they seem unwilling to acknowledge lime as the acidic vehicle of choice, allowing sliced lemon in ways that have bewildered many an American scientist at conferences in the UK. We can expect some spirited pushback from the States in response, as MAGIC is critical for the theoretical and observational definition of the Really Habitable Zone.

As to gin, juniper is acknowledged as the essential ingredient, and an exo-Juniper is defined, with the understanding that its tolerance for varied climatic conditions does not force strong limits on the RHZ, whereas what the authors call ‘ginspermia’ (the transport of juniper berries between the stars) is unlikely on planets with efficient harvesting and maximal gin production. The RHZ is, on the other hand, defined by the necessity for citrus fruits to thrive in a relatively narrow temperature range and a supply of H2O. The authors’ equation 1 encapsulates their assumptions on atmospheric modeling and planetary weather (the equation is, unfortuntely, too baroque to insert easily into the Centauri Dreams format).

The inner RHZ defined here is loosely based on ‘Recent Venus’ work available in the literature. Curiously, the outer edge coefficients of the RHZ equation appear to align with the founding years of a number of well-known gin distilleries, a fact the paper acknowledges but fails to follow up on. Thus the paper’s major shortcoming, described disarmingly by the authors themselves:

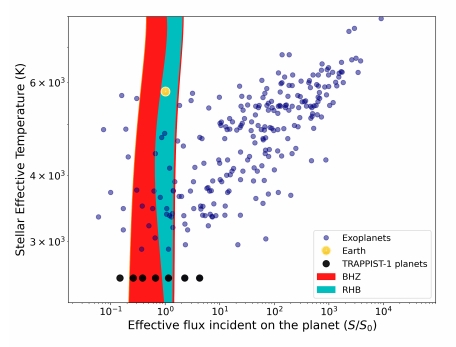

We had planned to carry out a statistical test to determine whether the populations of planets within and without the Really Habitable Zone were really different. However, the undergraduate student we’d expected to apply a Bayesian Machine Learning model has stopped answering our emails, so we merely suggest you follow astronomical tradition and look at the graph for a few seconds before drawing sweeping conclusions from it.

And here is the graph. Note that BHZ stands for Boring Habitable Zone, the authors’ term for more conventional models now in circulation:

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: As this figure shows, the Earth (lemon) is worryingly close to the outermost edge of the Really Habitable Zone (teal blue region). One might think that this is cause for panic, however, the authors have extensively tested and verified the existence of gins and tonic on Earth. Our vigilance in this matter is (nearly) unceasing. Credit: Pedbost et al.

This compelling work includes an interesting section on observational prospects for detecting gins and tonic on exoplanets (“As with many exoplanet papers, this one includes a section on wildly infeasible future observations which, though difficult, would undoubtedly have enormous scientific impact”). The authors assume 1 bar atmospheric pressure in their calculations, for reasons that should be apparent, and evaluate methodologies for detection of both gin and citrus, assuming tonic is ubiquitous because gin without it is “literally unthinkable.” How true.

The paper is Pedbost et al. (with what I take to be a liberal contribution from the ever reliable Chris Lintott), “Defining the Really Habitable Zone,” available as a preprint. Thanks for the pointer goes to my friend Ashley Baldwin, who knows the value of the occasional jest in dire times.

Although this paper is facetious, it raises some serious questions. Such as how can the U.S. government afford to fund the JWST when there are so many higher priorities? But one can also ask: If the U.S. government can print $2.2 trillion for Covid-19 relief, why not print a couple more billion for the JWST? And socialists might ask why not print still more money for Medicare for all, free college, public housing, urban renewal, etc, etc. Now I realize that technically the U.S. government is “borrowing” the money, not printing it. But a lot of reputable economists and political scientists have argued that voters in a democracy will NEVER vote for anyone who favors paying the money back. The sums are just too astronomical and the sacrifices just too severe. So the Federal Reserve is basically just printing money. Maybe there will be inflation, but maybe not. Compared to other currencies, the U.S. dollar is pretty strong.

What I’m suggesting with this long, shutdown induced ramble, is that maybe Modern Monetary Theory, aka the magic money tree, might conceivably provide NASA with the funding it needs to complete the JWST and accomplish its other space faring goals as well.

Or maybe MMT will lead to the breakdown of society. The only certainty is that we live in uncertain times.

I rather would not politicize this forum. But now that it happened anyway.

Medical care for all cost less in all countries that have a government run system, generally about ½ of the one found in USA.

Education up to a Ph.D should always be provided for free, I would not have become a researcher in a society where the parents would have been forced to pay.

Most importantly, keeping a population well educated and healthy is a benefit for said society and it will therefore win by such investment.

This is as far down the political track as I want to go, so let’s curve back to science and, in the case of the Really Habitable Zone, the satire on same.

Well in a veiled attempt to avoid politics and keep on the subject, let me stir the stuff some more by taking Paolo’s “Alcohol is a monster” point of view. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gin_Craze about a time in Britain when gin consumption was a major problem and not just a debating topic for clever astronomers.

Pictures of dead presidents on pieces of green paper and magnetized particles on metallic disks are just that. With fiat currency, the seigniorage is virtually the entire presumed value of the currency. However, the corresponding “goods & services” do not magically appear out of nowhere. Instead, the newly issued currency dilutes the total pool of currency. It takes to itself some of the power of every existing unit of that currency for exchange to “goods & services”. That includes your pocket and your bank account.

The most pressing question in my view is the proper pluralization of gin and tonic. Is it gins and tonic, as used in this article, or is it the more commonly heard gin and tonics? There is a less heard alternative, gins and tonics, which while odd sounding is perhaps more accurate.

Take care everyone as you remain isolated within your own real habitable zones.

I believe the Brits tend to go with gins and tonic, but my friends in the UK may well correct me! Nonetheless, these are Oxford folks who’ve come up with the paper, so I trust their judgment. In the States, the reverse seems to be the case.

I believe footnote 6 is relevant here.

Footnote 6: “Yes, gins and tonic, not gin and tonics. You want multiple gins, not more tonic”

I’ve tasted gin. It should never be pluralized.

Ah, but does the sole promising planet at TRAPPIST-1 have sufficient seasonality for the junipers? This also suggests a line of experiments to determine the shortest/longest seasonal cycle junipers can tolerate, which would enable determination of the stellar mass range that can support habitable planets.

Oxford counts Pythons Terry Jones and Michael Palin amongst its alumni , so the authors obviously have a lot to live up to. Flying the flag so to speak in addition to quaffing gin/s in it. Lamb allowing. Chris Linton took over from Sir Patrick Moore in presenting the BBC’s longest running show “The Sky at Night” and is Editor of the accompanying magazine of the same name.

Shame on all of those who support such kind of questionable “irony”. Alcohol is a monster butchering the lives of millions. To paraphrase J. Joyce, I can state that it destroys the mind, the body, the heart, the soul. On the contrary, a relevant percentage of those who smoke weed experience an increase in IQ and the rise of the uncommon ability to better perceive BOTH the tree and the forest.

Well alcohol may be bad for your liver, but weed is bad for your lungs.

But does a planet that supports weed but not gin and tonic actually create a civilization? Or just communities of exo-hippies living in yurts and enjoying the sunsets?

Comment of the day!

Come on Paolo, I appreciate your concern (really and sincerely) but life is full of choices. G and T’s work better for me than weed. Weed just makes me think I am smart, alcohol reminds me I’m not as smart as I think.

“I can state…”

You can but you are doing so poorly. I had a friend die of alcoholism yet the vast majority drink in moderation and suffer no ills, just as some over-hydrate to death yet the large majority benefit from drinking water. Welcome to the human race.

“a relevant percentage of those who smoke weed experience an increase in IQ”

I think you’ve come to the wrong blog to vent your evidence-free and off-topic assertions.

I look forward to the Irish telescope launching next March (coincidentally also called JWST, but fueled and co-sponsored by Jameson Whiskey). It should add much to the international flavor of this effort, even if its primary mission is to locate exosplashes of water.

And will the rise a fall of RHZs follow the path of gin drinking in England? As gin became very cheap compared to other spirits (gin is the only spirit where the flavor is added to the distilled alcohol, rather than part of the fermentation process), gin houses (even palaces) abounded and drunkenness became epidemic. Similarly, as telescopic observations of exoplanets became possible, even “easy”, the abundance of exoplanets exploded, providing a cornucopia of planets in the HZ, and possibly in the RHZ. Will the RHZ and HZ’s decline as we get better observations of these exoplanets and follow the decline in the popularity of gin? Will there be an equivalent trend to adding quinine to gin while Britain administered its empire, with astronomers adding effective planetary modeling to reduce the speculative fever where every planet in the HZ is deemed to be in the RHZ?

Sadly, despite my British birth, I no longer drink G&Ts. I do drink gin martinis, and like Bond, prefer mine shaken not stirred, but with an olive, not a slice of lemon. Cheers!

Only one way to settle this – go there and build a pub.

Cheers. Another breakthrough from Drs. G. & T. MAGICal thinking finally pays off.

Love it :)

Before I can offer any relevant commentary on this pressing subject I must personally conduct more research………………… There.

Obviously not only does the article help further constrain the parameters of what constitutes habitable zones but also whether said zones are worth inhabiting.

:D

Ironic Anglopomorphism, one of England’s greatest gifts to the world. Learning comedic delivery comes at such costs though.

I would not be surprised if intelligence and the use of mind altering substances were commonly linked. We use them to both dull thought and expand thought. Animals will seek alcohol as well. Perhaps being self aware is to have a place called self and mind altering substances allow us to explore that space.

This paper just might stand the test of time – for one day.

But it might have a recurring, synodic nature.

It has oft been observed that if the Earth is so inhabitable, then why

wasn’t it patented as a recipe so it could be put into wider distribution?

Economics and real estate combined give follow imperatives of scarcity and location, which proliferate abundantly in cosmic space, the best kind of course. In other words, the answer to Enrico Fermi’s question ( where is everybody? …You the LGMs.), is that it’s after hours in deep time and the pub is closed.

It’s all good that they start a program looking for worlds that are suitable for Junipers to grow.

But any program should also look at the 325 nm and 375 nm bands, to look for these bands only will exclude any false positives from any other type of water.

As this would detect the quinine which is an essential part of the necessary tonic water. I propose it be called a Schweppes detector.

“Juniper” does bring back a memory of decades back when I was working in a guidance, navigation and control group associated with a Space Shuttle upper stage intended to launch space probes to the Outer Planets.

On the grounds of a large industrial facility maybe close to a thousand of us were called into a cavernous conference room for a division sized rally, touting achievements and surveying the horizon. When it came to our hardware project, the speaker that day referred to our mission objective several times in a consistent manner, so to speak, but it was something like this: “It’s all very nice that some of you are working on a program to visit Juniper, but we have to pay attention to the basics around here.”

Naive as I was, I thought he had been raised on a farm or was a gardener. Maybe there was also an underwraps project headed for the planet Tonic?

Mission to Juniper! A mind-boggling concept, at least to the speaker… And yes, why not tonic?

I am all for the proposal of a mission to Juniper.

Especially if it do look for quinine, a substance that we indeed is in need of right now – and which appear to be in short supply.

So let make quinine the first objective for asteroid mining as well!

Paul, you are always a gentleman and a scholar. Coincidentally, I was having a gentleman’s gin and tonic whilst reading your prescient missive before retiring to a pleasant slumber. When one lives in South Florida a dose of quinine a day keeps the malaria away. PS The white elephant known as JWST may just be that outrageously expensive magic bullet that finds the very special needle we all know is hiding in the haystack of the Milky Way.

Yes, let’s send best wishes to JWST and hope for mission success. As to south Florida, I would say quinine is all but essential, so store in a good supply of limes along with the other groceries! As you’ve called me a gentleman and scholar, I will spring for the first round next time I see you.

Well

I sure feel like I need a drink after reading this!

It would be very interesting to meet you in person Paul, I’d buy you a drink out at the pub too.

Cheers

Thank you, Laintal. Gin and tonic is a personal favorite.

Thanks Paul

Given currents events I can only hope the US get this under control its day 9 of lockdown here!

Is this research repeatable? Perhaps the study should be conducted at a different location – the Eagle & Child comes to mind.

I much approve of the Eagle & Child. And yes, a good question that someone needs to address. How much did the venue play into the results?

Some nice Easter eggs in there:

I presume that Adams 1979 refers to the incomparable Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

And: it can hardly be a coincidence that in the graph the 7 Trappist planets are pictured:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trappist_beer

Excellent ! Merci Paul pour cette brillante analyse des Zones Réellement Habitables !

Merci, mon ami!

A Really Habitable Zone should also include bourbon and Coke.

Bourbon is aged in oak barrels that have been fired (heated on the inside to form a lining of charred wood – imparts color and flavor), used to age scotch and then imported from Scotland. Coke has a veritable list of ingredients including the purported decocainized coca leaf, the “Merchandize 7X” in its formula. And High Fructose Corn syrup.

From wheat (the base for bourbon) through oak trees (color & flavor) to corn is a fairly wide flora for any habitable zone.

I hope it’s not too late to ask a question of vital importance.

You all seem to have overlooked a telling detail in the last graph shown. There’s a yellow circle representing Earth. But around that yellow circle

I see a greenish outline. What does it represent? The prevalence of other beverages? Or the prevalence of the card game of gin? How does drinking gin affect card games? Does gin cause card games to evolve (or devolve) into other games, such as bridge, or basketball?

Enquiring minds want to know!

Enquiring mimes are probably curious, too.

They mention the Bayesian Machine Learning model. Well, of course the model has an active social life and is taking college classes, planning to go into fashion and theater…

Thanks for the article.

I interpret the greenish outline as a symptom of the authors’ uncertainty about whether lemon or lime is actually the preferable citrus for a gin and tonic. I suspect all but one of the authors favored the lemon, but the rogue author sketched in the green edge to register his disagreement.