It doesn’t take much to awaken my internal medievalist. On this score, Andreas Hein’s latest is made to order, looking at European cathedrals, long-term projects and starships. Is there an analogy that impacts long-term thinking here, or is the comparison too strained to be useful? Andreas is the Executive Director and Director Technical Programs of the UK-based not-for-profit Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is), where he is coordinating and contributing to research on diverse topics such as missions to interstellar objects, laser sail probes, self-replicating spacecraft, and world ships. He is also an assistant professor of systems engineering at CentraleSupélec – Université Paris-Saclay. Dr. Hein obtained his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in aerospace engineering from the Technical University of Munich and conducted his PhD research on heritage technologies in space programs there and at MIT. He is an INCOSE member, a Fellow of the British Interplanetary Society, and a Fellow of the Stanford Ignite – Polytechnique program. He has published over 50 articles in peer-reviewed international journals and conferences. For his research, Andreas has received the Exemplary Systems Engineering Doctoral Dissertation Award and the Willy Messerschmitt Award. Have a look at his take on the relevance for our interstellar future of some of the most beautiful structures ever built.

by Andreas M. Hein

1. Introduction

“You know,” he began, “I’ve been thinking about how we should go about interstellar travel, and it occurs to me that we do this much the same way the great cathedrals of Europe were built…” This is how Frank O’Connell, starts his talk in the science fiction short story “Cathedrals” by Allen M. Steele, featured in the book “Starship Century”. In that story, building a starship is considered an endeavor, spanning multiple generations. Those who work on it today are the bricklayers on which future generations will built. Bricks of knowledge, technologies, and inspiration, forming a structure, reaching for the stars.

The cathedral trope is a frequently used one: Mentioned at the memorable 100 Year Starship Symposium 2011 in Orlando, Paul Gilster’s Centauri Dreams book, etc. Examples abound. Former NASA Administrator Michael Griffin declares that we owe cathedral-builders “the ability to have a constancy of purpose across years and decades.” [2] Cathedral builders “learned how to organize large projects, a key to modern society. And, probably most important of all, the cathedrals had to be, for decades at a time, a focus of civic accomplishment and energy.” He continues to make the link between cathedrals and space programs by claiming that “the products of our space program are today’s cathedrals.” Krafft Ehricke, one of the space pioneers who developed the Extraterrestrial Imperative notes that “Like the giant cathedrals of the Middle Ages, Selenopolis will be the work of many generations” [3]. In a similar spirit, a radio show StarTalk by Neil deGrasse Tyson had the title “The International Space Station – A Modern Age Cathedral”.

But how were cathedrals really built? In general, no references are given for those claims. Is it really true that they were multi-generation endeavors, where the “baton” was passed from one generation to another? Was it really an incredible capacity to plan, which ensured that such a feat was indeed accomplished? And how were these megaprojects funded over such extended periods of time? Were the financing mechanisms really that sophisticated that NASA could learn from them? I first started doing serious research into these questions in 2015/2016. I was surprised to find that there is considerable literature on cathedral-building. My original objective was to “debunk” the cathedral “myth”. It seemed to me too beautiful as a narrative that what we are struggling to do nowadays, sustaining a multi-generational project, had been solved by those people in the Middle Ages. During my research, it indeed turned out that some of the narratives around cathedrals are indeed myths. They are not supported by current research. However, I was wrong. Cathedral-building, it turns out, may indeed provide hints at how we could sustain multi-general projects. But not for the reasons we commonly assume.

The following article provides insights into how these fascinating and awe-inspiring buildings were built and funded and what we might learn from them.

Figure 1: Rouen Cathedral and a starship (Credit: Wikipedia, Adrian Mann)

Putting cathedrals and space projects side by side, as in Figure 1, what are the implications? In these exemplary quotations, the cathedral symbolizes at least three things:

- A collective long-term achievement;

- A feat in long-term project management and engineering;

- A monument lasting for future generations.

Obviously, the analogy only works if these assertions regarding cathedrals are actually true. Among the three assertions, the third seems to be rather uncontroversial. Few will deny the cultural significance of cathedrals as monuments. The reaction to the Notre-Dame de Paris fire in 2019 on a global level seems to confirm that the cathedral has an enormous symbolic value, independently of individual religious beliefs. Hence, those who built the cathedral undeniably created a building which is a lasting monument many generations after construction finished.

It is important to define the key concepts that are used in the following. First, a cathedral is a church which contains the seat of the bishop. The bishop is a member of the Christian clergy. In the cases I consider in the following of the clergy of the Roman Catholic Church. The bishop’s authority stretches over a certain geographic domain, the diocese. The bishop is accompanied by a group of clerics that he needs to consult in all important matters. This group is called the cathedral chapter. The cathedral chapter is important, as it was often responsible for the long-term management of cathedral-building and ensured its continuity via its underlying endowment fund, called “fabric”. The bishop was often involved in the initiation of construction but at the later stages of the Middle Ages, the cathedral chapter was mostly responsible for the oversight of cathedral construction.

Cathedrals were far away from being a pure monument without utility value. “Thus, far from simply being a place of worship, the medieval cathedral was a multi-purpose structure, with some of the characteristics of the modern commercial mall, union hall, courthouse and amusement park” [6, p.455] “The role of the medieval cathedral was multi-faceted, with religious observance and ritual mixed with civil and commercial interests.” [6, p.456] Thus, considering cathedrals for their symbolic value alone would fall short. This is even more important when it comes to the value of the cathedral in relation to its cost.

In the following, I would like to focus on the point of view of project management, project finance, and systems architecting. There is a rich literature on building cathedrals. Examples are [5–7]. Also, the management of these projects was also subject to several publications by Turnbull [8–11], who asserts that gothic cathedrals were laboratories, where construction was a process of experimentation. Chiu [12] looks at cathedrals from the perspective of a history of project management. Financing of cathedral building has also been subject to several works, notably Vroom’s hallmark work, which presents several data sets of the financing history of several cathedrals [13]. Further publications have provided more or less quantitative accounts of cathedral financing [14,15].

Such an analysis would not only confirm or not confirm the appropriateness of using the cathedral as an analogy, but could also provide valuable insights into the drawing possible conclusions for current and future long-term projects, for example in spaceflight.

In the following, I will conduct a survey of the literature, combined with statistical analyses to shed light on how cathedrals were built and financed. From these insights, I will try to develop implications that can be generalized and potentially applied to future long-duration projects in the space domain.

2. Materials and methods

For the cathedral to be a long-term achievement in project management, including financing, requires the existence of a long-term project. In other words, at least some form of continuity must exist. According to the dictionary definition, a project is “an individual or collaborative enterprise that is carefully planned to achieve a particular aim” (Oxford Dictionary). I will interpret “carefully planned” in the following way: For a cathedral to be a long-term project, at least some plan must exist. For the aim of the project to be reasonable, adequate means need to be provided as well. This leads me to the following hypotheses, I would like to test:

- The cathedrals were built based on an initial detailed master plan;

- Construction was a continuous process that adhered to the master plan;

- Investments were continuously provided for the building process.

I use the existing literature and elemental statistics to answer the research questions pertaining to the cathedral. However, I will frame or express the questions and answers in the language of project management and systems engineering. I argue that this framing yields conclusions that can be sufficiently generalized to apply to current and future long-term, large-scale engineering projects. I am aware that such a reframing needs to be done with care, as such a translation from one context to another inevitably introduces losses and bias. Whenever adequate, I will make this process as transparent as possible. Did cathedral-building proceed according to an initial detailed master plan?

3. Were cathedrals built according to a master plan?

What makes this question difficult to answer is that no coherent set of plans for a cathedral has been conserved. Hence, it is not possible to compare an initial plan with the actually realized cathedral. However, the question can be answered indirectly. If the cathedral had a master plan, it would most likely have strived towards coherence, harmony, and symmetry. Hence, the occurrence of multiple architectural styles and asymmetry would hint at a divergence from the initial plans if any existed. Indeed, this is what can be found in most cathedrals, notably in cathedrals that have been built over centuries such as the Rouen Cathedral. For example, the towers of Chartres Cathedral were built during the 12th and 16th century respectively, and their design differs considerably. But even the nave and choir, the main part of the cathedral that was built during a relatively short period of decades shows considerable differences in its construction and style of, e.g. the flying buttresses [18, p.274].

These observations hint at continuous modifications of the design of new elements of the cathedral. Such modifications might be correcting errors of a previous architect [18, p.276], changes in style, and improving skills of architects. Furthermore, modifications were necessary when funding ran out and the original plan could no longer be executed [5, p.138]. As Scott [5] and Turnbull [11] remark, at least before the 13th century, detailed construction drawings with the right proportions and scale did not exist. Although models might have existed for discussions between master masons and the clergy, they were likely small and did not exhibit much detail. These results suggest that the design of cathedrals underwent continuous modifications of newly built elements. While a high-level design might have existed, prescribing the location of significant elements of the cathedral (e.g. towers), the detailed design of the actual elements of the cathedral could not have been prescribed in advance.

4. Was building a continuous process?

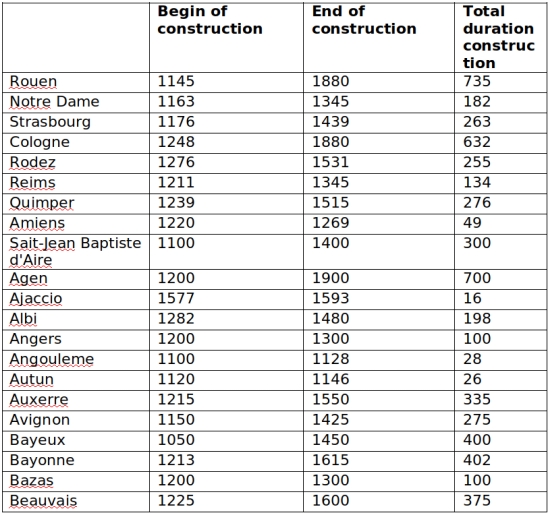

To start with, I will show via a simple statistical analysis that cathedrals were indeed built over centuries and then analyze how far the building process was continuous or not. I select a sample of 21 cathedrals built in the Middle Ages (Construction started before 1600), shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Sample cathedrals for which construction started before 1600

I looked into the distribution of how many years it took from the inception of the construction until the construction was declared completed. Figure 2 shows the results of the analysis with a median value of 263 years and mean value of 275 years. A group of outliers with construction durations between 600 and 700 years exists, notably the cathedrals in Agen, Cologne, and Rouen.

Figure 2: French cathedrals and their years of construction

The results confirm that cathedral-building was indeed an intergenerational endeavour and on average took 2 to 3 centuries to complete. This result is remarkably similar to results reported for a sample of English cathedrals in [3, p.39] of 250 to 300 years.

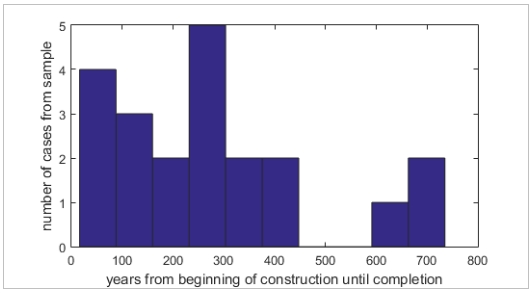

However, these results do not provide insights into whether the construction process was continuous or not. There is evidence that although construction was in many cases, continuous, intensity strongly varied. Often, construction went through periods of intense activity and long periods of moderate activity. Periods of intense activity were likely due to available funding [5, p.42] but also civil unrest, wars, plagues, [5, p.38]. Prak [23, p.387] notes that the construction of Canterbury Cathedral comprised 161 years of high activity and 182 years of low activity. Plotting the data from [5, p.40] for the Canterbury Cathedral’s successive active construction periods and periods of inactivity results in Figure 3. The lengths of these periods do not seem to follow a recognizable pattern.

Figure 3: Active and inactive periods of the construction of the Canterbury Cathedral

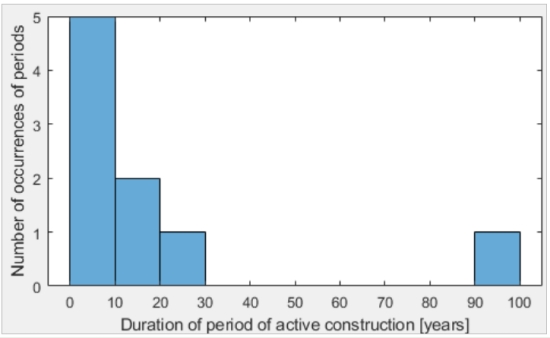

Counting the occurrence of active periods from longer to shorter ones results in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Distribution of active periods in the construction of the Canterbury Cathedral

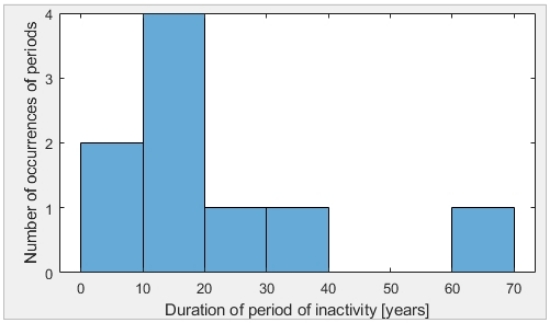

Doing the same for inactive periods results in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Distribution of inactive periods in the construction of the Canterbury Cathedral

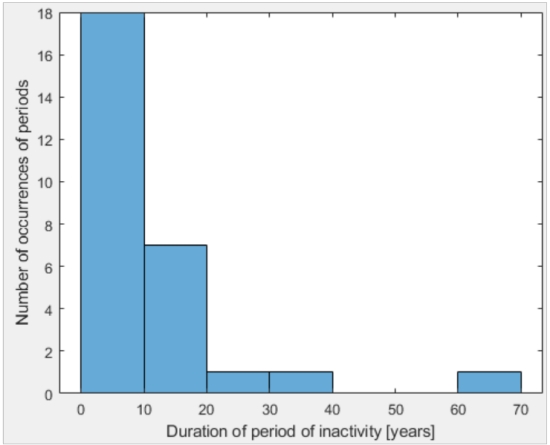

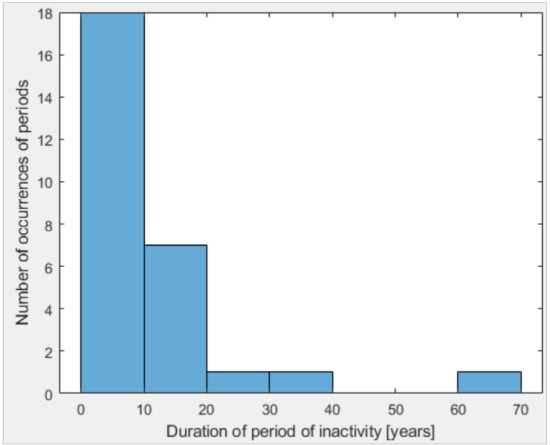

Further data for Osnabrück and Utrecht Cathedral is taken from Vroom [13]. Periods in which funding is spent on construction and furnishing are counted. The results for all three data sets can be seen in Figure 6 for the active years and in Figure 7 for the inactive years for all three cathedrals. It can be seen that the length of the vast majority of construction periods falls between 1 and 30 years. Longer construction periods, however, exist (between 60 and 70 years and 90 to 100 years).

Figure 6: Distribution of active constructions periods for Canterbury, Osnabrück, and Utrecht Cathedral

A similar distribution is obtained for inactive periods, where the vast majority of periods falls between 1 and 40 years.

Figure 7: Distribution of inactive periods for Canterbury, Osnabrück, and Utrecht Cathedral

Fitting both distributions with a power law and exponential curve leads to an R² of 0.97 and 0.99 for active periods and similarly, 0.97 and 0.99 for periods of inactivity. Such distributions might be linked to the probabilistic distribution of weather phenomena such as drought. If there is a correlation between the two, this would confirm Scott’s argument that funding uncertainties are linked to the occurrence of harmful weather conditions, which can be considered random [5].

To summarize, the results imply that active construction periods of cathedrals typically had a duration between 1 to 30 years with periods of inactivity of similar length between them. Only in rare cases are active and inactive periods of longer duration observed. This confirms that cathedrals were not built continuously until completion, except for rare cases such as Notre-Dame de Paris.

5. Were investments continuously provided?

A common conception within the space domain seems that cathedral building was financed by the public in the most general sense. Fortunately, there are several publications that took an in-depth look into the financing of cathedral-building in the Middle Ages. Kraus [14] analyzes the economics of cathedral-building and identifies factors that have contributed to a relatively short building duration. There are factors which pertain to specific stakeholders, such as a strong commitment by the ecclesial family, which was by far obvious. Some bishops had no interest in cathedral-building and did not commit personal funds to the undertaking. In the seminal book “Financing Cathedral Building in the Middle Ages” [13] Wim van Vroom identifies numerous funding sources for cathedrals that were built north of the Alps, notably the bishop, chapter, pope, king or lord, municipalities, and the faithful in general.

Interestingly, funds from the bishop and chapter were only important when construction was initiated. On the long run, the contributions from the faithful of the diocese comprised the majority of the funds for construction. As the faithful of the diocese were a large and geographically distributed group, systematic and long-term fundraising campaigns were organized. The two main incentives provided were indulgences and relic worshipping. Indulgence trade became a huge economic activity, and relic worshipping was organized systematically to increase its efficiency. These two activities were accompanied by collecting campaigns within the diocese.

An interesting aspect is what fraction of total economic activity has been devoted to cathedral-building. Lopez [16] argues that the poor performance of urban economies north of the Alps compared to those in Italy was due to the large resource consumption of cathedrals. Vroom demonstrates that this thesis cannot be maintained and demonstrates that the average expenditures for the cathedral at Utrecht, amounted to the equivalent of the wages of 81 unskilled workers its construction from 1395 to 1527 [13]. Values of the same order of magnitude are displayed by Vroom for the Exeter Cathedral, Osnabrück Cathedral, Segovia, Sens, and Troyes Cathedral. These yearly expenses were far below those of palaces, castles, and fortifications. Hence, cathedral-building seems to be far less resource-consuming than one might expect.

Regarding the financial stability of cathedral-building, Vroom concludes that “Observed over the long term, the general pattern of cathedral fabric expenditures paints a picture of instability” [12, p.462] “In Durham, one chronicler tells us, the pace of construction in the early twelfth century rose and fell with the magnitude of the offerings made there.”[12, p.115] Scott [5] ties instabilities in cathedral funding ultimately to the instability of agricultural yield in the Middle Ages, the main source of income. Weather anomalies such as droughts could severely impact income, which then reduced the amount of funding available for cathedrals.

However, over time, mechanisms were put in place to stabilize cathedral financing. During the thirteenth century, a church office, the vestry, was created for managing the fabric. The vestry was administered by the cathedral chapter. Bishops and canons were then “obliged to give it a fixed proportion of the church income” providing at least some stability to financing cathedral construction [6, p.272]. Furthermore, “Sometimes, these miracles were connected with the building works.” [12, p.116]

Hence, financing for cathedrals was far from stable, although mechanisms were developed over time to mitigate these risks, notably via establishing the vestry, which actively managed the cathedral fabric.

6. Discussion

The previously presented results confirm that cathedral building cannot serve as an example for a successful, continuous, large-duration project. The results seem to imply something far more interesting. Cathedral building was confronted with an “extreme complexity of the project, the lengthy period of time required for construction, and the repeated interruption of the building process” [5, p.140]. These are characteristics, which are often ascribed to space programs [18]. In the following, I will discuss what mitigation strategies cathedral builders used and how these strategies might be transferred to the context of space programs.

Extensibility of the cathedral architecture

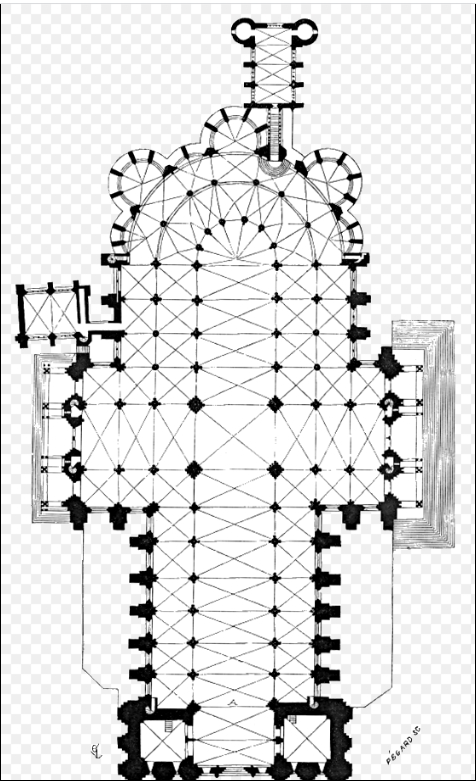

As Lopez [15, p.273] describes, cathedrals needed to provide the possibility for church service throughout their whole construction period. “Cathedrals-in-progress were given temporary wooden roofs, and makeshift services were conducted in these half-built structures.” “These services were separated from the building work by temporary screens, some of them rather robust structures that were never subsequently removed.” The ability of the cathedral to enable church service throughout its construction was probably crucial in sustaining construction work over decades and centuries. At any point, the church could be used for its intended purpose. In today’s marketing terms, one can talk about a minimum-viable product (MVP) (cathedral that allows for church service) to which new features (new elements of the cathedral) are added. There are elements of the cathedral that are obviously modular such as the tower(s), the spire, and chapels. These elements can be added without interfering with church services. Fig. 1 shows the floorplan of Chartres Cathedral, where the side chapels can be seen as the half-circles and rectangles on the top and on the left.

Figure 8: Floorplan of the Chartres Cathedral (Wikipedia)

Scott [5, p.142] even goes further than that and argues that modularity was a key enabler for cathedral building over its construction duration of decades to centuries. Modularity was not only present in the large elements (tower, nave, etc.) but also in sub-elements such as columns, arcs, etc. This allowed for a sub-division of work down to individual stones, robust against various uncertainties and interruptions in construction. Interestingly Scott takes inspiration from Herbert Simon regarding modularity and how it is able to mitigate uncertainties.

Trans-generational transfer of technological capabilities

According to Billington and Mark [19], “the great cathedrals were constructed by relatively well-paid, highly skilled teams of masons and carpenters, with supporting staffs that included the apprentices who insured the continuity of skills” [6, p.38] According to White [20], “we see a sublime fusion of high spirituality and advanced technology.” Indeed, it seems that the investments from the faithful were channelled into one of the few areas during the Middle Ages where considerable technological progress was made by constantly developing and transferring skills in diverse art forms but also civil engineering and architecture [21]. One notable document in this respect is the only written first-hand account of the engineering and architecture behind Gothic cathedrals, is the Carnet of Villard de Honnecourt [22].

Furthermore, just to provide one example for the engineering ingenuity of the Middle Ages: The flying buttresses were introduced as structural support for very tall vaulted structures against horizontal loads such as winds [19,23]. Little seems to be known about the process of how knowledge was transferred between generations of builders [5,11]. Turnbull [11] argues that no global and accurate plan existed, but low-level templates were used. Scott [5] discusses the possibility that modularity allowed for continuity in building activity in the absence of a master plan. Hence, it can be speculated that cathedral building was robust against knowledge loss by providing a modular architecture where new contributions could be “plugged in”.

7. Cathedrals and starships: Lessons learned?

I will now suggest some conclusions from the cathedrals to long-term, large-scale space projects, exemplified by the starship.

From the previous sections we can summarize the following characteristics of cathedral-building as a long-term, large-scale engineering project:

- Value-delivery via a minimum viable product: The way cathedrals were built ensured that the main function of the cathedral, church service could be performed throughout the whole construction period. Hence, continuous value delivery was ensured.

- Project finance: Cathedral-building was subject to instabilities in available funding. However, organizational innovation mitigated this risk. Formal institutions and mechanisms were created to increase the reliability of cash flows. Fundraising campaigns along with spiritual “products” such as indulgences, relics, and miracles were vital elements of the financing strategy.

- Extensibility: The architecture, in the sense of the components and relationships between these, enabled the continuous addition of new components (towers, chapels, flying buttresses) to extend the church. Hence, the difficulty in determining if a cathedral construction is ever “finished”.

- Knowledge transfer: Knowledge transfer by or between key personnel such as architects and artisans, was facilitated by the dissemination and documentation of their knowledge. Furthermore, this workforce was highly mobile, enabling the cross-fertilization of building projects in different regions and even countries. These enabled not only the transfer of explicit knowledge in the form of documents but also the transfer of tacit knowledge.

- Stakeholder management: The network of stakeholders around a cathedral construction project contained different entities such as the ecclesiarchy, municipalities, representatives of worldly powers, the construction workforce, and the faithful in the diocese. The management of the diverse value flows, and notably, financial flows seem to have been as complex as the physical cathedral.

- Expenditures: The financial and human resources spent on cathedrals were much smaller than for palaces, castles, and fortifications. The expenditures were typically on the order of 10s to 100s of annual wages with large gaps between periods of activity [13].

From these characteristics, I can now speculate on lessons to be learned for future long-term, large-scale space projects. Rather than suggesting specific solutions, I will discuss general principles and how they might translate into solutions for such projects:

- Modular architecture: Modular architectures do not only exist for buildings. Modularity also exists for knowledge, software, etc. Cathedrals somehow provided interfaces where future builders could continue their work, such as wall and roof sections. Hence, on the one hand, they could build on previous work or, on the other, they could do so efficiently via building on these interfaces. Furthermore, this approach left important degrees of freedom, so that future builders had relative freedom in their designs. Today, we would call such an architecture an open architecture. Modules can be integrated via well-defined interfaces. An open architecture approach ensures flexibility and extensibility, able to absorb uncertainties. In the context of starship development, subsystem technologies could be matured independently but with a clear definition of interfaces and constraints. Such an approach would ensure that these technologies can be integrated at some point in the future. “Interfaces” in this case should be understood broadly, such as the fundamental compatibility of technologies, information exchange between organizations which develop the technologies, etc.

- Value delivery / minimum viable product: Even for long-term projects, thinking about how intermediate value can be delivered is important. For example, for interstellar travel, an intermediate version of the propulsion system could be used for interplanetary travel, as has been suggested for laser sail propulsion [24–26].

- Financial stability: Funding for a starship project is likely to be unstable, which has been demonstrated repeatedly for past and current space programs. What institutional and financial mechanisms could be developed to mitigate the risk from instability? The example of the cathedral has shown that financial stability was established over time via institutions. Recently, foundations and non-profits have emerged which provide funding for research on interstellar travel such as the Breakthrough Foundation and the Limitless Space Institute. Compared to the Middle Ages, a vast number of mechanisms and instruments for financing long-term projects exists today.

In short, cathedral-building can indeed be considered an enormous feat, precisely because those cathedral-builders were facing many problems we and future starship-builders will also face: uncertainties in funding, interruptions, trans-generational knowledge transfer issues, stakeholders who want to see results quickly. They used, deliberately or not, approaches for solving these problems, which we would today call minimum viable product, modular architecture, and institutionalized fundraising. Such an interpretation of cathedral-building puts less emphasis on inspiration and visionary thinking as their conditions for success but highlights the role of mechanisms, institutions, and the structure of the building. How can we use these principles for long-term space programs? The one thing we know from those gigantic monuments is that multi-century programs are possible. For us, there are no excuses for why we could not do what they did.

References

[1] M. Schiller, Benefits and Motivation of Spaceflight, (2008).

http://mediatum2.ub.tum.de/?id=654918 (accessed December 31, 2016).

[2] M. Griffin, Space exploration: real reasons and acceptable reasons, Quasar Award Dinner, Bay Area Houst. Econ. (2007).

https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/168084main_griffin_quasar_award.pdf (accessed December 31, 2016).

[3] K.A. Ehricke, Lunar industrialization and settlement-Birth of polyglobal civilization, in: Lunar Bases Sp. Act. 21st Century, 1985: p. 827.

[4] B. Bercea, R. Ekelund, R. Tollison, Cathedral Building as an Entry?Deterring Device, Kyklos. 58 (2005) 453–465.

[5] R. Scott, The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral, 2011.

[6] P. du Colombier, Les chantiers des cathédrales: ouvriers, architectes, sculpteurs, Paris, 1973.

[7] J. Gimpel, C. Barnes, The cathedral builders, Pimlico, 1983.

[8] D. Turnbull, The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral, Contemp. Sociol. 34 (2005) 40.

[9] D. Turnbull, Masons, tricksters and cartographers: Comparative studies in the sociology of scientific and indigenous knowledge, Taylor & Francis, 2000.

[10] D. Turnbull, Inside the gothic laboratory:” local” knowledge and the construction of Chartres cathedral, Thesis Elev. 30 (1991) 161–174.

[11] D. Turnbull, The ad hoc collective work of building gothic cathedrals with templates, string, and geometry, Sci. Technol. Hum. Values. 18 (1993) 315–340.

[12] Y.C. Chiu, An Introduction to the History of Project Management: From the earliest times to AD 1900, Eburon Uitgeverij BV, 2010.

[13] W. Vroom, Financing Cathedral Building in the Middle Ages, Univ. Chicago Press Econ. Books. (2010). https://ideas.repec.org/b/ucp/bkecon/9789089640352.html (accessed January 4, 2017).

[14] H. Kraus, Gold was the mortar: the economics of cathedral building, Routledge & Kegan Paul Books, 1979.

[15] J. James, Funding the Early Gothic Churches of the Paris Basin, Parergon. 15 (1997) 41–81.

[16] R. Lopez, Économie et architecture médiévales: Cela aurait-il tué ceci?, Ann. Hist. Sci. Soc. (1952). http://www.jstor.org/stable/27578887 (accessed January 5, 2017).

[17] P. Ball, Universe of Stone: A Biography of Chartres Cathedral, Harper Collins, 2008.

[18] E. Rebentisch, E. Crawley, G. Loureiro, J. Dickmann, S. Catanzaro, Using stakeholder value analysis to build exploration sustainability, in: 1st Sp. Explor. Conf. Contin. Voyag. Discov., 2005: p. 2553.

[19] D. Billington, R. Mark, The cathedral and the bridge: Structure and symbol, Technol. Cult. (1984). http://www.jstor.org/stable/3104668 (accessed January 4, 2017).

[20] L. White, Dynamo and virgin reconsidered, Am. Scholar. (1958).

[21] H. van der Wee, Review: De financiering van de kathedraalbouw in de middeleeuwen, in het bijzonder van de dom van Utrecht by WH Vroom, J. Soc. Archit. Hist. (1984). http://jsah.ucpress.edu/content/43/3/267.abstract (accessed January 4, 2017).

[22] R. Bechmann, Villard de Honnecourt: la pensée technique au XIIIe siècle et sa communication, (1991). http://www.openbibart.fr/item/display/10068/1052496 (accessed January 4, 2017).

[23] R. Mark, H. YUN?SHENG, High Gothic Structural Development: The Pinnacles of Reims Cathedral, Ann. New York Acad. (1985).

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb14578.x/abstract (accessed January 4, 2017).

[24] P. Lubin, A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight, J. Br. Interplanet. Soc. 69 (2016).

[25] A.M. Hein, N. Perakis, T.M. Eubanks, A. Hibberd, A. Crowl, K. Hayward, R.G. Kennedy III, R. Osborne, Project Lyra: Sending a spacecraft to 1I/’Oumuamua (former A/2017 U1), the interstellar asteroid, Acta Astronaut. (2019).

[26] A. Hibberd, A.M. Hein, Project Lyra: Catching 1I/’Oumuamua–Using Laser Sailcraft in 2030, ArXiv Prepr. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2007.03654.pdf (2020).

My own particular observations concerning the question of whether or not it is possible to create an interstellar vehicle that will the constructed over the period of ages required to do so seems to boil down into 2 basic questions: firstly u need to have basically somebody who’s kind of a ‘weirdo’ to undertake the project; the first thing that comes to my mind immediately is um Elon Musk. He’s absolutely perfect as the guy who would be heading up such a project since he’s somebody who like to dream big and to take on projects which are really out there.

Second question that is of paramount importance is whether not you can undertake such a massive project in this political and financial environment, and in my opinion yeah this time it is probably all most likely impossible.

I’m a terrible skeptic when it comes down to under taking any kind of venture when their does not exist the least bit stability within the world community and the fact that there are so many political factions out there all vying for the precious dollar so who is going to be willing to pony up the money to do this rather fantastic project?

The time is NEVER right to start out long-term projects. It is never stable enough, there is never an absence of factionalism or conflict, or even war. The cathedrals were built during the Middle Ages, a time of constant warfare, political upheaval, oppressive religious fanaticism, peasant revolts, paranoia about Muslim expansion in the middle east and north Africa. And of course, the medieval world had its plagues, pogroms, witch-hunts, false Popes, famines and Asian nomad invasions as well.

Maybe they were just lucky enough NOT to have an Elon Musk.

Henry, I sort of agree with you, but I also think some times are better than others. Europe of the era of cathedral building was a time when the Catholic Church had filled the power vacuum left by the fall of the Roman Empire. In essence, the Church became a unifying power structure, for a period, and that allowed for these long-term projects to happen. It also allowed for the financial and labor requirements to be accessed. I do think some periods may be better, or more conducive, than others to a long-term project. I don’t think now is one of those times.

In spite of great wealth, peace, stability, highly advanced technology and sophisticated social organization, the Pax Romana wasn’t a very good time for long term, multi-generational projects either. Construction projects such as the road or aqueduct system don’t really count, since they could start making a return on investment in one emperor’s lifetime, long before they were actually completed. Other, long term activities, such as the Dutch land reclamation projects, seemed to have no religious origins or motivations at all. Many of the projects we are discussing here may be better understood as sequences of discrete steps, each building on previous ones, than as a long term evolutionary process.

Egyptian pyramid building went on for thousands of years, but each individual monument was always done during one Pharaoh’s lifetime (or his immediate successor’s!). The Chinese Great Wall was built over a long period, but each individual segment was erected to meet one, isolated, tactical defensive requirement.

The settlement of the Pacific archipelagoes by Neolithic navigators (which has been proposed as a potential model for galactic exploration in our distant future) took centuries, but it was essentially a long list of individual voyages, not a “long-term project”. The necessary maritime technology may have evolved over centuries, and the immediate pressures favoring expansion persisted for many lifetimes, but that doesn’t mean there was an overall master plan. I could go on.

A cathedral would probably have long term financial benefits for the community that built it (by attracting travelers and pilgrims, etc), but you could say the same for amusement parks.

Disney World was built in my lifetime, but other attractions and their supporting infrastructure are still being opened in Central Florida today.

I suppose the point I’m trying to make is that historical examples are dangerous, because as in all social sciences, you can always cherry-pick your facts to prove anything you want. Unfortunately, the human mind is extremely adept at making connections and seeing patterns where none may actually exist.

History does not always repeat itself, even though at times it does appear to rhyme.

Another example of very long term project planning and execution from early European history comes from the planetary engineering conducted in Holland to reclaim land from the sea. It was possible to initiate and carry out generational projects that did not yield concrete results until long after all the original builders had died. I suspect that the limiting factors in such works were not technological, but social. The spiritual motivations of the cathedral builders spanned human generations, but the dikes, canals, windmills and other water-control structures built in the Low Countries were built by businessmen, politicians and bureaucrats for hard-headed practical reasons; long-term national goals–and profits. I find it difficult to visualize modern governments and corporations undertaking that sort of forward thinking today.

Thank you for this comment! Indeed, reclaiming land in the Netherlands is a fascinating project and definitely worth a deeper look.

Figuring prominently in the history of the Shire horse is the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden’s drainage of the Fens in eastern England, which he was contracted to do by the Crown in the seventeenth century; it was another long-term project that was carried out for its future benefits. It is significant–and possibly pivotal–that at the time both the Netherlands and Great Britain were ruled by powerful–but not all-powerful–monarchs, who could make such long-term decisions (despite the existence of parliaments in their nations). Also:

I do not favor such leadership, but it is interesting that the Soviet Union, which was ruled by a virtually all-powerful Premier, was able to pour so much funding, talent, and materials into space travel, which enabled them to accomplish so many “firsts.” But for internal Communist party political squabbles that delayed their manned Moon mission decision until 1964 (which resulted in the hurried N1 rocket test flights that all failed), Soviet cosmonauts would likely have reached the Moon before NASA astronauts.

Brings to mind the ongoing saga of building and deploying the (just delayed again, [was anyone surprised]) Webb Telescope.

Of course the cathedrals were built to plans.

The Monastery complex of San Lorenzo del Escorial, Spain, built by Philip the Second who had a mania for paperwork, all the documents, plans, bills, reports, still exist and are kept in State Archives.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Escorial

1563, architect Juan Bautista de Toledo

Thanks for your comment! This might be true for cathedrals which were built after the 13th century (and your example is from the 16th century) but not for cathedrals, where construction started before. Scale drawings did not exist in that period, as I explain in section 3 of the article. For the sample of cathedrals in the paper, construction started overwhelmingly before the 13th century (Ajaccio is an exception).

Absolutely *fascinating* article! Couldn’t help but leaving this comment here. Thank you very much!

Thank you very much! I really appreciate it!

An evocative concept to be sure, although I’ve never been a big fan of generation ships – generations of trip time as opposed to build time, that is (the two do correlate). Being at heart an optimist, I figure we’ll always be coming up with a better, faster way to both design and propel ships, and thus extended build projects are almost doomed to fail.

I would also point out the extreme cultural narrowness of this report. What of the other multigenerational projects of history? The Mayan temples? The Great Wall of China? The Great Pyramids? The major mosques? The major temples of Buddhism? Of Hinduism?

Thank you for your comment! Cultural narrowness is definitely an issue and ideally, I would have liked to take a broader range of projects into account. For example, Mayan temples were also constructed over centuries. There are two main reasons for choosing cathedrals, however. None of those projects you are mentioning, except maybe the Great Pyramids, are used as a trope in the space domain as often as the cathedral. Another issue is data. Today, there is a rich data set and numerous publications on cathedrals, including quantitative data, which makes statistical analyses easier to do. Hopefully, this will change and more publications will be available for a broad range of multigenerational projects.

Readers may find these two videos of useful reference in regards to this essay in terms of historical context as well as structural…

* Cathedral by David Macaulay:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uZDpmN5apF8

In case the above link does not work for you, try this one:

https://mediaspace.msu.edu/media/PBS+-+Cathedral+-+David+Macaulay/1_0w2cp0g4

* Building the Great Cathedrals on Nova PBS Television:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/building-the-great-cathedrals/

Thank you for those links! I watched a number of documentaries about cathedrals but had not seen those before.

Thanks for a fascinating article. I much enjoyed the read. I was also left wondering if in our world we are capable of such a long-term project. The article made me think about the idea of METI (messaging extraterrestrial intelligence) and some of the ethical debates surrounding that (some of which I’ve been involved with). One thing that I’ve often felt is that the rush to send messages is, in part, a product of a strong and very understandable desire to be the ones alive when contact happens. SETI is not for the impatient–it may take decades or centuries before contact is made (if it ever is), if we just listen. Thus, according to some METI proponents, we need to send messages now. Why the hurry? I think largely because it would be a lot more fun to be alive when contact happens than to miss the show. Can we mobilize scientists, engineers, politicians, and many others to work on a project for which they will never see the end result? Clearly, we did in the past, so perhaps we can again, but I’m not convinced our current worlds is patient enough for that. Great article.

Thank you very much, I appreciate it! One common explanation for short-term thinking are shorter political and financial cycles, which require the delivery of results within a few months or a few years. However, things were not that different in the Middle Ages. Fortresses and castles were built within a few years or even faster, out of necessity. Cathedrals were built with rather modest investments and faced constant financial problems. I am not sure things have fundamentally changed. Regarding the end result: An important point I try to make in the article is that cathedrals could be used without being finished and nothing was apparently missing. Hence, not seeing the finished result was maybe not that important. Today, the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona is still under construction but few people who visited the church probably realized that it is not yet finished. An analogy for METI would be a continuous submission of messages at different degrees of sophistication.

The problem is not short-term thinking. It’s the difference between need and want. Fortresses were needed; cathedrals were wanted. The motivations are entirely different and therefore the resource allocation.

Building starships and doing SETI/METI are wants, and only of a small number of enthusiasts. They are not needs of anyone and certainly not the broader community. Cathedrals are a poor analogy for the interstellar enterprise in my opinion.

Absolutely agree with your notes.

I want also to point attention that people who invested in cathedral was not so interested in final “product“, it was invested with hope that those deeds will be accounted as good in the Judgment Day, for every personality was important his own deeds and religious motivation , but not the result.

Ron, I understand your point regarding the difference between needs and wants. But if cathedrals were wants and starships are wants (that I feel, is what you are implying), with what respect is it a poor analogy then?

That’s a fair point. I was jumping between different thoughts and misspoke. A few days later I can’t recall what I was specifically targeting with that last sentence.

Andreas, that’s an interesting point, but I’m not sure I agree with you that things aren’t much different now as compared to the Middle Ages. Certainly there are similarities–humans have social tendencies that cross many generations. But I would argue that cultural differences are profound. Cultural context, in my view, basically programs us in certain ways (language is a good example) and that shapes how we respond to our physical social environment–including how we think about long-term and short-term projects. I am not a specialist in the Middle Ages, by any means, but I find it difficult to believe that modern humans do not think in ways significantly different from people of that period. In fact, I don’t really think we can talk about how “modern humans” think as a whole. There are major differences based on race, class, cultural context, socio-economic status. (Note that I do not accept the idea of the psychic unity of humans–I think culture profoundly shapes our ways of thinking and, thus, we are actually quite different from each other, depending on the social environments in which we mature, even if we have the capacity for self-reprograming through learning, such as in learning another language.) So my question is more one of whether or not, given the current cultural climates in highly technologized countries, at least, we actually think in a way that would allow for long-term projects of the sort you suggest. I kind of doubt that Americans do, at least. Not sure about other societies. It certainly is an interesting problem.

Also, as an aside, I’m wondering how that works with an unfinished space ship. Seems like a very different problem from an unfinished building, since the building is not an entire ecosystem upon which the inhabitants’ lives depend.

John, I understand your point and it is incredibly hard to make general statements about how much those factors contribute or not, given that they are hard to define. I would just like to stress that at least for the history of technology, there is a general tendency to overestimate how different things are today compared to former times and numerous times, I discovered that certain technologies and approaches which are advertised as innovations actually existed a long time ago, often under a different label. Obviously, it all depends on how general or specific you define things. Another observation is that specific, local contexts often trump macro tendencies. For instance, certain countries might be hostile to innovation but a specific group of people might still be very innovative. The Middle Ages are not known to be a very innovative period but gothic architecture and cathedral-building were highly innovative, linked to the development of many new technologies.

Why the fascination with cathedrals? Could this reasoning not as easily be applied to the building of the great wall of China or the Egyptian pyramids or, more recently, to the human and cancer genome projects or the hunt for the Higgs boson and the pursuit of fusion power?

Does there even have to be a physical legacy or a concerted effort? No government stated that they wanted to achieve fusion power or invent the radio or internet. The drive to advance tech, alleviate suffering, advance education and abolish suffering are multi-generational efforts that have been sustained as a byproduct of general “getting on with it”… Can there not be a “cathedral for the stars” built out of the byproduct of just getting on with it?

To me the fascination and constant comparison to the building of cathedrals is a just naval gazing – an easy way to capture the nostalgia of a needy (localised and romantic ) audience. “Cathedrals” have been built throughout history and continue to be built now.

Thank you for your remarks! I agree that there are many other projects that are worth looking into and they should be part of a wider comparison of long-duration projects. My guess of why cathedrals are used as an analogy for large-scale space projects is that the utility of the latter is often questioned and therefore, cathedrals are used as an analogy, to point at projects that also had no apparent immediate utility. As I show in the article, this seems to be far from actually being the case, as cathedrals provided and still provide value as a multi-purpose building.

Based on Dr. Hein’s analysis, we can say that we are actually in the midst of a cathedral project to go to the stars: no different really than the building of cathedrals. The duration will likely be generations long, the funding is discontinuous, the utility is incremental and value is delivered over the life of the project, and there is a more or less rigorous master plan that is subject to correction and modification. One wonders what people involved in building a cathedral thought about the ultimate prospects for finishing them. Maybe there were a few zealots and a large number of ambivalent citizens who viewed the whole project with, at best, mild curiosity. Only on completion would they be enthusiastic supporters of the effort: much as I suspect people will be once we launch a starship.

Thank you for your remark! This is an interesting point and fortunately, there are accounts on how different stakeholders saw cathedrals. There were cases where there was even open hostility between the inhabitants of the town and the clergy who commissioned the cathedral, between masons and the clergy etc. Interestingly, the records from the cathedral “fabric” (fund) show that a large fraction of funding came from the wider population. Hence, at least for the cases where we have these records, it seems that people were willing to donate to cathedral-building, which indicates that they were supporting it. This is probably quite different from starship-building, where I can tell from personal experience that the general public is interested, but considers it rather as a curiosity.

I agree that designing and building a starship will likely take the efforts of many people over a long period of time. It will certainly take multiple generations, if a generation is defined as 20 years. For instance, the ISS took about 25 years from when NASA was directed to start it until most of of it was in orbit.

I don’t think a starship could be initiated by a government, though, because it is too speculative and the costs, goals, and schedules are too uncertain. Like a cathedreal, I think a starship design would be started by the faithful (Non Governmental Organization), though perhaps not through a Church.

I am inspired more by how certain large software projects get started, gain momentum, and how they function. The software projects I find very instructive are Linux, Wikipedia, and Minecraft. You wouldn’t expect an artisan to work on a cathedral without being paid. Why would skilled software developers contribute to Linux without pay? Why would someone contribute articles to Wikipedia without pay? And why would people spend hours working on a collaborative project in Minecraft, and actually pay for it? Yet it happens, and these projects will probably continue for a very long time.

So I think a starship effort will start out more like a big software project than a cathedral.

Dear Randy, Thank you for this comment. Open source projects are fascinating for various reasons. And indeed, 100 Year Starship was initially intended to be heavily relying on open source-style development. I looked into open source projects a while ago and it seems that they work well for software which is useful for many people (“common good”) and the examples you cite seem to confirm that. Nowadays, the open source spirit has expanded to the space domain and open source CubeSat components do exist, although manufacturing is not that straightforward. Also the “Libre Space Foundation” is a dedicated space organization working on open source technologies.

To coordinate and cooperate over a long term will require homogeneity rather than diversity of the supporting population, and that is one of the differences between cathedral-building Europe and today’s potential starship builders. The measure of a man’s humanity and his society’s greatness is when he plants a shade tree, knowing that he will never sit in its shade.

In democracies, corporate thinking is synched to cycles of quarterly (financial/earnings) reports and political thinking is synched to election cycles: stockholder and voter approval are major criteria in decision-making. In government projects in the US, secondary and tertiary feeders at the trough is de rigueur: government bureaucracies, corporate (contractor, subcontractor, sub-subcontractor) bureaucracies, lobbyists, constituents (employees of corporations) etc.

And a multigenerational project might take more than one Elon Musk.

An interesting analogue to Elon Musk is Suger, who initiated gothic architecture. He was a kind of combination of Elon Musk, Tacitus, and Richelieu:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suger

Good call, Andreas! Had never thought of that comparison. Nice.

The lessons learnt may be neglecting the “Fundraising campaigns along with spiritual “products” such as indulgences, relics, and miracles were vital elements of the financing strategy.”

The cult aspects of the medieval period were key to the success of fundraising. How do we apply that to an Interstellar project?

Consider the cult emblem chosen for the new ‘Space Force.’ Although this appropriation of what is essentially a commercial trademark loses its appeal for me personally, it was certainly intended to tap the cultural energy (cult fandom) and complete market penetration of the Trek franchise.

Then there is the ethos of contributing labor and tithing to atone for one’s wrongdoings. In the modern sense, might the wealthy classes who have contributed to ecological devastation and societal dysfunction seek redemption by contributing to a Great Work in an attempt to justify themselves?

Relics abound in space. What is a moon rock in private hands worth? The trade in space relics, as collectables, can’t be discounted. And don’t forget the Power of the Shwartz; i.e. merchandising.

Lastly miracles: Short of the discovery of alien life, or first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence (the actual ‘miracle’) there is the promise of miracles and the willingness of believers to pay for any signs that sustain their faith. Even NASA has learnt that lesson in its regular news feeds about the signs hinting at the possibility of life on Mars, past or present.

More real, tangible and perhaps honourable are the scientific and technological ‘spin offs’ that a multi-generational Interstellar project can offer the world in exchange for sustaining its funding. Ensuring these relics are freely and fairly shared with the faithful could certainly work miracles in the multi-generational effort.

Ultimately, if life is to be preserved on the one and only planet on which life is known to actually exist, there will need to be, not just a multigenerational project, but a multi-millennial one to stave off overheating from an aging Sun. Saving all the life forms a planet has from extinction seems like one of the noblest causes any intelligent species could have. (The National Park movement is another example of a multigenerational project that people of all religious/anti religious stripes tend to agree on.)

I suspect that in today’s political environment, any proposal to sell off public lands, including the National Parks, to private investors, (at pennies on the dollar, of course!), would immediately be seized upon as desirable, if not necessary. Our recent experience with the Nevada Welfare Cowboys in their theft of rangeland for their own grazing use and the movement to privatize all public institutions for corporate profit should be all the caution we need. Ever since Odysseus’ time piracy has always been justified by being presented as entrepreneurial virtue or ideological purity.

Fortunately not all nations follow the current US ideology. National parks are still preserved and treasured in many countries. The UK is even starting rewilding by reintroducing European bison. Other megafauna to follow.

Let’s skedaddle outta here?

Thanks for the link Robin. It shows that very gradually widening Earth’s orbit is a least theoretically possible.

An obvious “minimum viable product” for a star ship, would be colonizing a comet or Kuiper belt object. Requires very independent life support and a viable community without much physical exchange with the rest of humanity.

I could see political or social dissidents colonizing an outbound comet, equipping it with some sort of engine, and converting the orbit to hyperbolic. The colony is then a generation ship. As they consume the parent body for fuel and building materials, eventually what remains is the star ship they will use to complete their trip.

Probably at that point to some other star’s Kuiper belt, since that’s the life they’ll be used to, but they’ll migrate inwards towards the star, while launching similar colony ships.

The real question is, what engine? A comet can be selected to be rich in hydrogen, but P-P fusion is absurdly difficult, and the Deuterium content would not yield a very impressive Delta v for interstellar purposes.

Alas, this is not a good time for maintaining cathedrals. https://www.dw.com/en/france-arson-suspected-in-major-fire-at-nantes-cathedral/a-54226732

This post calls to mind a book that may be of interest, “Universe of Stone: A Biography of Chartres Cathedral” by Philip Ball.

“For the first time, they began to believe in an orderly, rational world that could be investigated and understood. This change marked the beginning of Western science and also the start of a long and, indeed, unfinished struggle to reconcile faith and reason.”

To me, the most important aspect is that any long term project is not a “waterfall”, but rather delivers value during construction, whether for religious services, security (Hadrian’s Wall, Great Wall of China), or environmental (Holland’s dykes).

To that end, I do not see building a starship, and in this context, a worldship, as offering that continuous value. Instead, I see building space habitats in a modular fashion, extending them to become worldship in size, correcting errors, and adding new technology. Finally, after ironing out the bugs through experience, interstellar capable engines and powerplant are added to propel the habitat towards the stars. This may not even require a big jump, as island hooping between Oort objects in the space between the stars may be the best way to achieve the goal over time with such a large structure.

A more conventional fast starship might be built over time using autonomous robots, requiring little human input for much of the construction. This removes many of the raised complications – human dedication, financing, etc.

For the really fast ships, I see making the smallest vehicles possible that can fab everything a colony needs at the destination, transporting biological material as cells or minds in non-biological substrates. If laser arrays are to be the energy supply to propel these ships, then robotic built arrays in space that can be used for a myriad of other purposes would be the way to go, as they do not commit resources to a single-use project.

Starships, worldships et cetera: an excellent idea if such small, isolated ecosystems can be organized and sustained in a manner that keeps them thriving for large multiples of millennia.

But after the failures of a few fitful attempts in the USA and the former USSR, it would seem that this existentially critical research for human survival in deep time has been abandoned.

The comparison of cathedrals and starships was the basis of Allen Steele’s science-fiction story “Cathedrals” which I commissioned and published in the book Starship Century in 2013. Note that it starts with the session I chaired at the 100 year Starship conference in Orlando in 2011. Thus it links todays starship activities to future starships, relates both to cathedral-building. All are long-term struggles.

Jim

Jim, I appreciate that you shared that article with me! I added it as an introduction to the article. Again, thank you!

A wonderful article Dr. Hein. I haven’t read all of the comments yet but I’m reminded of the 10,000 year clock and the Long Now Foundation and the thinking that has gone on during that project. There is an interesting talk online given by Alexander Rose to Google which might be of interest to people on here. Long term planning will become more and more essential if we are to have a long term future. It should include projects such as interstellar travel and many other things which we can probably have a continuing good discussion about. For me it would include things like population stabilization, improvements to efficiencies of resource utilization, ecosystem management (versus pillaging) and several others. Congratulations again on the article.

Thank you very much for these remarks and it is great to hear that you liked the article! Indeed, today, there is more than ever a need for successful large-scale projects. The knowledge for how these can be successful will be crucial.

Andreas, your post is eloquent and your ideas are something we should consider when planning a journey to the stars. Whether it’s cathedrals, dikes, pyramids or walls, we have learned something as humans about cooperation for the greater good from these endeavors. And I understand that we should study history so as to learn from it, but I cannot escape the fact that most innovation and achievement comes completely out of the blue. In 1883 many a learned man or woman would say that man was not meant to fly, that it was impossible, yet 20 short years later on the dunes of North Carolina it happened. And only 66 years after Neil and Buzz took a short walk about on the surface of the moon. The history of Earth is a series of evolutionary and human breakthroughs that have little to do with what came before. I agree we need to study the past, but not to dwell on it too much for fear we will continue to live within it.

Thank you very much for your comment! I completely agree that it is difficult to predict innovations, in particular on the long term. A lot has been written about this. However, we can certainly study patterns, make comparisons, make careful generalizations etc., to eventually apply them to future projects, with the necessary care. This article was a modest exercise in extracting some principles for long-term projects but they need to be validated by a further diverse set of examples.

Agreed, and thank you Andreas for a most interesting post!

The big question, why especially Generation Starship should be such longterm project – I suppose there is not scientifically grounded answer, we are talking about one of multiple sci-fi ideas.

Probable there is some tendency (may be unconscious) among SETI/ METI biased community to found the New Religion, SETI/METI concepts are not going well with scientific methods , so there is request to find alternative – religion.

Additional note.

When medieval society began long term building projects, there was one, but most important requirement – they had long period (thousands years) existing ability, experience and technology to do so.

Meanwhile even new version of capsule that delivers couple of humans to Low Earth‘s orbit take tens of years. I do not tell about human return to the Moon… It our “cathedral” present moment, not very problematic concept of “generation ship”, problematic – in multiple humanity related aspects.

Start now experimenting with simple off-Earth biospheres and the project will take less time than anticipated. Today’s technology will anyhow shorten construction times compared to earlier huge projects with the achievement of a livable, self-sustaining world the real difficulty.

“off-Earth biospheres”

The first step is on-Earth self-contained biospheres, or at least a biosphere with a strictly limited input. This is, unfortunately, still some way off. Only then is it worth the effort of moving the technology into space.

An off-Earth biosphere can be made from its beginning independent of influences except light and other radiation. No accidental contamination is likely.

I have in mind simple experiments, say, with algae and protozoans to begin with.

“I have in mind simple experiments, say, with algae and protozoans to begin with.”

Sounds good. But I believe it is more sensible to do it first here on Earth before moving on to the much greater expense of doing it in space.

Valuable insight was gained with the Biosphere 2 experiment. I don’t consider that a failure at all since things were learned. The first space colonies would not have to be 100% closed.

Also, if one looks at the Space Studies Institute as an institution designed to promote and ultimately bring to fruition the vision of large O’Neill type space colonies, perhaps that could be considered similar to the first steps towards cathedrals.

I did not say that Biosphere 2 was a failure nor did I say that a space habitat would have to be 100% closed. You are putting words in my mouth. Don’t do that.

My statement about being closed is about not admitting matter, particularly any possible alien biological items. As far as I know any biosystem has to admit energy from outside.

A simple biosphere in space would be able to do just that — admit only energy. Simple life forms could give clues as to a balanced environment — which would still have to receive external energy and emit some energy.

I certainly did not intend to “put words in” your mouth. I believe you must have misinterpreted. My statement was not about what you said. I was adding my own points and I merely chose to do so as a response to your post to keep it close to that topic. You mentioned biospheres in general, I brought up Biosphere 2 and added my own thought. The same goes for my statements about space colonies.

Still have to do it from simple models on up.

Nobody truthfully said Biosphere 2 failed even if it didn’t do what was expected. That’s the point…

Don’t those globes with seaweed and shrimp (and bugs) prove that a simple enclosed ecosystem can work, at least for a while?

The problem with matter enclosed systems is that recycling 100% is well-nigh impossible. For long duration interstellar flight, this might be a serious problem. At least that is the opinion of Claude Piantadosi in Mankind Beyond Earth.

Of course. A closed system will eventually reach equilibrium and shut down. There has to be an external energy source.

Here there are all these minichanges and readjustments in the surroundings that will interfere — cloudy weather, shifts in the ground, and such that can be eliminated in space.

I a, only talking about a closed matter system. It is still an open energy system.

This is what I am talking about: A complete, self-contained and self-sustaining miniature world encased in glass

These sort of totally enclosed systems can be built on Earth. No need to make them in space with all teh associated costs. Today, I would modify those aquaponics farms in transport containers to become totally enclosed as test. Cheaper than doing something similar on the ISS, and they have gravity too.

Biosphere II was too ambitious IMO, especially for the technology of the time. Something simpler and more engineered seems more appropriate. Measuring the recycling efficiency is going to be important for world ship slow boating to the stars without pit stops.

Indeed. I’d like to see another biosphere or two on Earth, not least because I find it a bit appealing.

Maybe those and space experiments can be financed by multibillionaires like the guys building their own spacecraft.

What strikes me here is that cathedral building is more akin to self-organized process driven by some collective intention. At least, it is what I realized after reading the article and learning about details of building and financing. Cathedral building succeeded despite the discontinuous financing, the abscence of detailed plans, and long periods of little-to-no activity. Today’s big projects go bust even if one of these complications shows up. Maybe it’s really about different mentality or some fundamental aspect of society that made cathedrals possible and our current big projects so fragile (by comparison). I often hear something like “Modern world has no place and time for megaprojects”.

But comparison of interstellar flight and cathedral building immediately picks out one model of it’s development: colony ships. The parallels are straightforward:

The MVP is an independent colony in near-Earth space.

Modularity is the addition of more powerful space drive, maybe langing/mining gear, and living space. “Now we’re not confined to Lagrangians, but can go to asteroids; now we’re able to land on other planets and use their resources; then we add power and thermal management for outer Solar System; ultimately, we go to the stars”

The driving force could be something like the ability to diversify, not to be confined to one planet, one model of society, one political system or something like that. If we extrapolate globalization, the ability-to-live-different (but not downshifted) could eventually become very, very valuable.

If we really recognize interstellar flight as a mega-project, colony-ships starts to seem much more robust path than fast ways to reach the stars.

Fast-flying unmanned probe has too much risk to give more questions than answers. Like, we know now that Tau Ceti e is habitable and there is a complex biosphere, but we won’t be able to know much about compatibility with that biosphere, because without knowledge of exact chemistry we cannot even model this here on Earth. To investigate this, we need a lander probe, twenty times more expensive. But from what we know, we suspect there would be trouble, and on other nearby inhabited worlds as well. We still have not learned how to manage long-term-closed ecosystems, and we still think in terms of payback-within-one-generation, which sets a really hard ceiling to all our endeavours.

With Cathedral-ship, we just go to the system when we are ready. If we find it’s really much more troublesome than we expected, we mine some asteroids and exomoons and set sails for another system, arriving there in scant 189 years. Almost the same time that took Notre Dame to be built, and much less than the age of First Worldship, now a museum and popular tourist attraction point in the L1…

Where do you get that Tau Ceti e is a “habitable and there is a complex biosphere”? According to this information that exoplanet sounds anything but habitable:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tau_Ceti#Tau_Ceti_e

I intentionally mentioned a planet which is not in the top, because the current top-list is far from final form, and ESI may well be inaccurate. Some steaming super-earth with suitable temperatures only at the poles (but pronounced cooling water-cloud albedo feedback) may well turn out more habitable and suitable for colonization (which is far from being the same!) than a planets with higher ESI. In example, a planet with right earthlike insolation, mass and radius, but 200 bars of N2, which sets the surface supercritical and is hard to distinguish from more earthlike atmosphere, or a true Earth twin with complex biosphere, but incompatible biochemistry which forces to use sealed environments.

IMO, as a general rule the worlds with complex biosphere are not suitable for colonization, because of the biospheric compatibility issues. It is very underestimated today. It may well turn out that the only solution is to “drive out” native biosphere and seed the planet with lifeforms brought from Earth somehow, so the best is to look for very young planets which have not yet evolved anything past prokaryotes. Maybe even planets with abiotic oxygen atmospheres, which would fail to produce complex life on their own. Both types of worlds – young and abiotically oxidized, but stable – may be quite rare and we’ll have to travel tens of parsecs to them, so this again favors milti-generational ships.

Have you seen the stars tonight?

Would you like to go up on A-deck and look at them with me?

Have you seen the stars tonight?

Would you like to go up for a stroll and keep me company?

Did you know

We could go

We are free

Any place

You can think of

We can be

Have you seen the stars tonight?

Have you looked at all of the galaxy of stars?

Paul Kantner and Jefferson Starship

Hijack the Starship!

“To fly as fast as thought, to anywhere that is, you must begin by knowing that you have already arrived.” ? Richard Bach, in Jonathan Livingston Seagull: instructions to Jonathan from his preceptor/mentor Chiang, who teaches him to fly at perfect speed, i.e. instantaneously from any point in the universe to any other.

Which invokes aspects within the concept of intentionality.

You can find some Andreas Hein papers at

http://exoplanet.eu/bibliography/?title=&author=hein+a&year_start=&year_end=

Thank you, Jean for posting the link! I appreciate it!

Space cathedral like projects always was a good place for corruption.

Meanwhile our real ability is limited by space wigwam (ISS) even this wigwam took tens of years and billions of dollars… But it is real ability of our technology.

When homo sapience began to build “cathedrals” he has all required to di so:

technology ,materials and possibility to deliver materials to required place.

With our present technology we have to invest efforts to more advanced space “wigwam” constructions and economically adequate space transport.

Please tell me what large-scale human endeavor is NOT a “good place for corruption”? Did this corruption stop every such project as a result? Certainly not.

“You know what the fellow said – in Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

? Graham Greene, The Third Man

So-called purity is fine, unless it leads to stagnation. Then it is its own form of corruption.

Our inspiration for building a first starship should not be the construction of a Gothic cathedral, but the first cathedral. From Wikipedia, Dura Europos was built in the third century when Roman Emperor Constantine directed bishops to sit on chairs (“cathedra”) and occupy a magistrate’s building (“basilica”). It was made by bashing out a dividing wall in an ordinary house. A starship might be built similarly from space habitats, as others here suggested. Even the puniest first endeavor to a comet or Sedna might carry unique cargo – for a metaphorical illustration, examine the mosaics from that Wikipedia article and estimate the race of Jesus.

This is an ingenious analogy you make. I had a preconceived notion that it would be a stretch too far! Not so! Your writing is clear and offers a fascinating insight into how we might apply ancient knowledge to realise a future for humanity beyond the confines of our home planet.

Adam, Thank you very much for your comment and I really appreciate that you like the article!

Mr. Hein, are you familiar with The Ultimate Project? I did not see it mentioned in your References.

https://centauri-dreams.org/2008/06/18/the-ultimate-project-to-the-stars/

https://centauri-dreams.org/2008/02/26/the-ultimate-project-10000-year-journey/

Here is a link to the presentation on the project. Note page 7 on the PDF file:

http://www.interstellar-probes.org/the-project/

http://www.interstellar-probes.org/wp-content/uploads/TheProject.pdf

Thank you very much for pointing at this interesting project! I hadn’t heard about it before. Given the enormous size of the project, I wonder what intermediate steps would be, which would render the project more robust to disruptions.