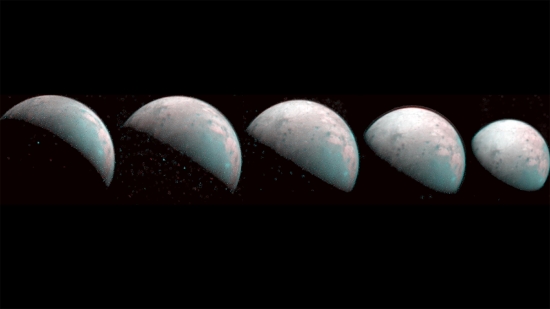

Have a look at Ganymede as seen by the Juno spacecraft on December 26, 2019, the day after Christmas (and a day and time that now seems impossibly distant given all that has been going on closer to home). Jupiter’s largest moon is also the largest satellite in the Solar System, bigger even than Titan, and 26% larger than the planet Mercury, though far less massive. Our view comes courtesy of Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument.

Image: These images were taken by the JIRAM instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft on Dec. 26, 2019, providing the first infrared mapping of Ganymede’s northern frontier. Frozen water molecules detected at both poles have no appreciable order to their arrangement and a different infrared signature than ice at the equator. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

Three-quarters the size of Mars, Ganymede began turning up in science fiction early in that genre’s development, as in Stanley Weinbaum’s “Tidal Moon,” which ran in the December, 1938 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories. Begun by Weinbaum and finished by his sister after his death, the tale depicts a surreal, warm Ganymede, a world of large oceans with massive tidal effects causing global flooding. These days we put a lot of emphasis on Jupiter’s tidal squeeze as we consider energy sources for maintaining Europa’s ocean. Ganymede, too, is thought to contain an internal ocean, with terrain features showing disruption by tidal heating.

Robert Heinlein’s 1953 novel Farmer in the Sky involves a terraformed and colonized Ganymede, and my personal favorite is Poul Anderson’s The Snows of Ganymede (1954), mostly because it triggers memories of a battered Ace Double, though it’s an otherwise negligible fragment of a great writer’s work. But I’d better stop there — references to the moon in fiction could go on for some time.

Image: Originally published in Startling Stories in 1955, Poul Anderson’s novella appeared as one half of an Ace Double in 1958.

Although the place is less hospitable than depicted in early stories, Ganymede has lost none of its scientific interest. This is the only moon in the Solar System with its own magnetic field, which produces interesting effects at the poles, bombarded as they are by plasma from Jupiter’s vast magnetosphere.

Alessandro Mura is a Juno co-investigator at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome:

“The JIRAM data show the ice at and surrounding Ganymede’s north pole has been modified by the precipitation of plasma. It is a phenomenon that we have been able to learn about for the first time with Juno because we are able to see the north pole in its entirety.”

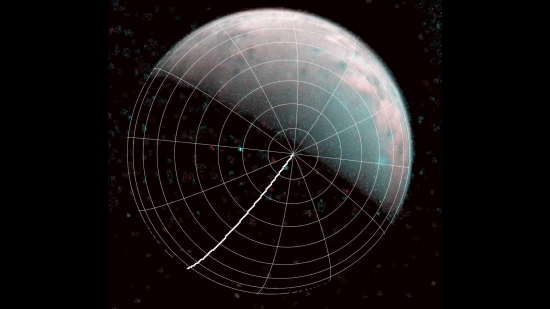

What’s happening here is that Ganymede’s magnetic field lines draw charged particles along them to the poles, disrupting the crystalline structure of the ice. The phenomenon can be tracked because such ‘amorphous ice’ shows a different infrared signature than the crystalline ice found at the moon’s equator. Although designed for infrared studies below Jupiter’s cloud tops, JIRAM has proven effective for studying the Galilean moons whenever JUNO makes a fortuitous pass. The instrument collected 300 infrared images on this flyby, with a closest approach of roughly 100,000 kilometers. The spatial resolution is 23 kilometers per pixel.

Image: The north pole of Ganymede can be seen in the center of this annotated image taken by the JIRAM infrared imager aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft on Dec. 26, 2019. The thick line is 0-degrees longitude. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

Our knowledge of Ganymede is going to skyrocket in 2030, when the European Space Agency’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer mission begins its observations. After flybys of Callisto and Europa, JUICE will enter an elliptical orbit around Ganymede. Launch is scheduled for 2022.

Today’s xkcd is relevant to our interests:

https://xkcd.com/2336/

More seriously, There’s a report on Venus that has some very interesting implications for what sort of worlds exoplanets might be:

https://www.space.com/venus-active-volcanoes-coronae.html

If planets can remain geologically active without plate tectonics, that affects what environments it’s possible to have.

Excellent point.

Here is a list of fiction media where Jupiter’s (and the Sol system’s) largest moon is the setting:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter%27s_moons_in_fiction#Ganymede

A question: I know Ganymede is within Jupiter’s intense radiation belt (only Callisto is outside it of the four Galilean moons), but just how intense is the belt where Ganymede is in terms of affecting future settlements?

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/radiation.php#id–Types_of_Radiation–Radiation_from_Space–Trapped_Radiation

Scroll down to the relevant exposure table.

The Earth receives about 0.14 rems day at sea level from a combination of cosmic rays and natural/man made radioisotopes.

By way of comparison Io receives 3600 rems/day, Europa 540 rems/day and Ganymede a more modest 8 rems/day at its magnetosphere “shielded” equator . A 2.5 year Martian mission would incur a radiation penalty of about 50 rems – assuming no solar storms .

A dose of 500 rems would kill promptly. A cumulative dose of 75-200 rems over a month is enough to cause radiation sickness, birth defects and much increased risks of mos cancers in later life. So Ganymede though nothing compared to its inner two compnIons is no easy abode for human life.

Callisto ironically receives less radiation than Earth at a paltry 0.01 rems/day.

Just wondering what the levels are on Mars surface per day? On the Moon and Mars there are plenty of lava tubes but Callisto would be great for surface base activity. Would Jupiter’s magnetosphere protect it from strong solar storms? What of Titan with its thick atmosphere and inside of Saturn’s magnetosphere but occasionally passing out of it.

“Saturn magnetises its moon Titan”

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn14717-saturn-magnetises-its-moon-titan/

Floating cities in its thick atmosphere would be easy to build from the many satellites near it. Structures are 7.266 times lighter then on earth, 100 earth pounds equal 13.76 pounds on Titan! Plus a beautiful view of Saturn and its rings! Sounds like my next vacation spot!!! Plenty of propane to keep you warm too! And there’s more, water ice to keep you wet and to make oxygen.

Titan may not be that bad to live on above the thick tholin haze. Just how high could a city made from hydrocarbon plastics float in Titans deep atmosphere? Gravity 1/7th of earths, plenty of hydrogen from the methane and hydrocarbons to fill the cities balloons, may be able to reach altitudes as high as 260-380 kilometers (160-235 miles) above the surface. Temperatures may range from -120 to-150 degrees Fahrenheit at these levels.

Let’s Colonize Titan.

Saturn’s largest moon might be the only place beyond Earth where humans could live.

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/lets-colonize-titan/

Probing Titan’s Atmosphere.

https://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2013/20130824-probing-titans-atmosphere.html

Protected from solar and cosmic radiation.

https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/internal_resources/1460/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305893951/figure/fig10/AS:614306232160299@1523473427427/The-main-layers-of-Titans-upper-atmosphere-and-its-illumination-by-solar-UV-blue.png

In the not to distant future hydrocarbon factories in Titans atmosphere will be producing huge amounts of products for the lively frontiers of the solar system.

I figure Titan’s main problems are keeping the moon’s atmosphere out (HCN is a component) and insulating your habitat from the cryogenic temperatures outside. In vacuum you won’t have to worry about thermal conductivity and convection sucking your heat away.

Would humans want to live on the surface of a planet without an atmosphere? For example, Enceladus apparently has relatively low radiation exposure, though I don’t have a number ( https://futurism.com/how-do-we-colonize-saturns-moons ) and it is thought water may be within “tens of meters” of the surface in some places. Nonetheless, with 1% of Earth’s gravity, a base would need to be about half a mile beneath the surface to have an Earth-like pressure from the ocean above it. This would offer substantial radiation protection. On Ganymede, gravity is a full 14% of Earth’s, so the equilibrium depth for atmospheric pressure would be more like 200 feet under solid ice, but still a respectable shield. Why live in terror of pinhole leaks and cosmic rays when almost everything of interest on the moon (except minable meteors) is even further below?

Meteoroid impacts would indeed be one of the highest concerns for those residing on the surface of a world without a substantial atmosphere for protection. Living underground would resolve this issue for all but the larger space rocks and ice balls.

The next question is, could and would normal baseline humans (us) want to dwell underground for the majority of their lives and never be able to go anywhere without being either in a spacesuit or vehicle for protection?

Even if they do, would it be healthy for them both mentally and physically? Needing to get outside in nature is not just some quaint luxury as studies have shown. We may be adaptable to certain degrees, but we are still basically primates of the savannas.

We need to accept this before making further and much longer ventures into space. Orbiting in a collection of tin cans for a year with Earth right below, or going to the Moon and back in two weeks is not the same.

Our space agencies are neither as knowledgeable nor prepared for long-duration missions with human crews to other worlds or staying in space for years or decades as they would like to let you think – or, more accurately, as the general public thinks without investigating the facts.

If you need more evidence, read here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2012/09/11/the-psychology-of-space-exploration-a-review/

Not saying humans should not explore and settle space in person on a permanent basis. Things may work out better than I fear. But I think we need to be more honest with ourselves so that we don’t end up with a collection of disastrous expeditions and premature cancellations.

I also suggest people study up on the folks who have explored and stayed in the polar regions of Earth. Especially regarding men who thought they could be John Wayne and tough it out, only to find their coping mechanisms being inadequate thanks to a society that expects people, especially men, to take it like a man.

Society is a blind herd animal that does not care about the individual, despite what the propaganda wants you to think. This will have a major negative affect on our personal ventures into space, which even now still largely consist of military males enduring a matter of month circling our planet. Look at the records and data.

It seems to me that building Earth-like space habitats will be far preferable to the contortions needed to build anything that has any semblance to habitability on or in any other planet or moon.

Given the interest in Mars, I was intrigued by Zubrin’s suggestion that a small fleet or rovers include several to take high definition pics of the surroundings to be used to make a detailed VR environment for exploration back on Earth. Extend that to the whole of Mars, or indeed any world, and anyone would have the ability to explore such worlds. We might all become “Mechanical Turk workers, looking for interesting things for an onsite rover to physically examine. For space habitats with low communication latency with the surface, robotic avatars could be used to explore physically.

Unless one really must live on an alien world with all the inconveniences, this seems like a viable way to live well and yet have the freedom to spend time exploring and more on different worlds.

Thanks for this brief and succinct run down!

Ashley Baldwin,

Like a couple other people mulling over your assessment for the Mars mission, I began wondering what the rems/day would be on the surface. Then I noticed that the 50 rem trip extended over 2.5 years

(~912 days) would provide an rem level per day comparable to sea level Earth ( .054 /day ). This suggest to me that there is a probability of a high intensity event over the 2.5 year mission rather than that the background level cumulative comes out to the number provided. If true, then consequently, the shielding issue is different: need for an alert system for routine days and safe harbor for the storms.

Whether there is a similar variability in the Jovian environment, I am not certain. But since the Galilean satellites are rotating synchronously with their orbital rates, back and front side exposures might be of consequence as well. Some surface feature differentiationis due to impact levels of debris, but there could also

be hemispheric coloring due to radiation exposure too.

All these comments based on looking for ways to sneak onto Mars or Ganymede…

BR

A correction to my earlier inquiry. Your original description of Ganymede and its equatorial belt covered that part.

In a slightly altered universe, Doctor Evil intones “Liquid hot plasma”

If there is active vulcanism on Venus then the short listed Discovery atmosphere sampling-cum-short term lander DaVINCI concept will find unequivocal evidence as soon as 2026. Let’s hope it gets picked.