In Shakespeare’s famous lines from The Tempest, the spirit Ariel addresses Ferdinand, prince of Naples, now grieving over the death of his father in the shipwreck that has brought them to a remote island in an earlier era of exploration. The lines have an eerie punch given our discussion of the changes humanity may bring upon itself as we adapt to deep space:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange…

From this has emerged the modern shadings on ‘sea-change,’ yet another Shakespearean coinage that has enriched the language. I thought about The Tempest while reading through the Working Track Report from TVIW 2016, a symposium in which these adaptations took center stage. The new edition of Stellaris: People of the Stars (Baen, 2020), discussed last Friday, contains the short report, prompting this examination of its conclusions along with a look at some of the fiction and non-fiction that takes up the bulk of the volume, all on the topic of human transformation.

Species Bifurcation at the Oort

In what sense will interstellar travelers be humans like us, and in what sense will they become a new species? One point that emerged in the discussions in Chattanooga was that adaptations to our species will be mission-specific. Exploratory expeditions have the need to adapt to issues like isolation and long confinement as well as, depending on spacecraft configuration, low gravity or other controllable environmental factors. Actual colonies have far different needs: Long-term adaptation to an environment possibly much unlike Earth and the need to support and sustain a growing population. The kinds of human engineering we’ve been discussing come into play, though through a natural process of development, destination by destination.

Imposing genetic and/or physical changes will be slow and adaptive, and doubtless the process will only be possible if begun and examined thoroughly in a space-based infrastructure right here in the Solar System. A multi-generational human presence in space also allows the social structures to develop that can support life off-planet, though these will doubtless evolve within specific mission parameters.

The generation that leaves the Solar System for the first time may face sharp distinctions in its mode of travel. Shorter exploratory missions to nearby stars make their own demands, different from those experienced by worldships that move at much slower pace, producing generations that are born and live out their lives on the vessel. In a sense, worldships can be seen as antithetical to interstellar colonization, if as the working track participants did, we make the assumption that spacecraft on this scale develop their own kind of inhabitants:

Worldships are an end in and of themselves. Moving such a large biosphere to another star system would likely take centuries. If a worldship would be viable for the projected duration of the mission, then it would most likely be viable well in excess of that timeline. Thus, a worldship is a colony; once established, attaching engines or even an interstellar drive to a worldship may provide mobility, but to what end? Furthermore, if it is used merely as a vessel to transport colony and crew, then what is the guarantee that they will want to leave the habitat once the destination is reached?

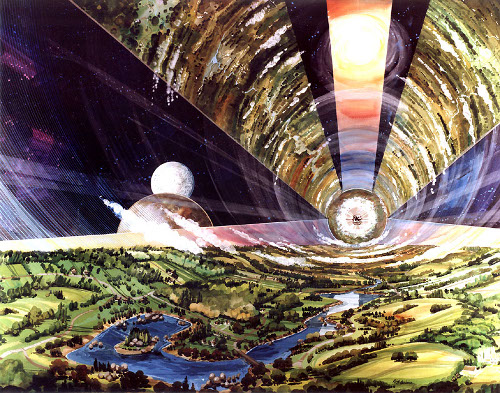

I’ve written before about the prospect of an important bifurcation in our species on this issue. Those who inhabit massive space structures — perhaps hollowed-out asteroids, or arcologies ‘grown’ in space by future forms of nanotech — and those who live on planetary surfaces and choose to travel through faster technologies to planets around other stars. I can imagine ‘slow boat’ travel between the stars as humans move gradually out into the Oort Cloud exploiting cometary resources and eventually moving into a presumably similar cloud around the Centauri stars, for example. Here we’re talking about missions in the thousands of years, and ‘crews’ — inhabitants — who may well choose to move on to another system after studying the first.

By contrast, those shorter exploratory missions, given the problems of propulsion, may themselves be, at minimum, decades long and likely centuries. Here the Working Track saw the need for deep sleep:

…interstellar exploration will most likely require some form of metabolic suspension. While such medical technology is still science fiction, it has its roots in present-day advances in surgical techniques, in the as-yet-unexplored functions resident in what has been called junk DNA, and in lessons learned from vertebrate animals which can successfully survive freezing temperatures without damage to cells caused by the formation of ice crystals.

Alternating crew shifts into and out of hibernation could sharply reduce the subjective passage of time, with ramifications for both social engineering and life support systems.

Image: The vast interior of an O’Neill cylinder presents a more spacious view of what a worldship might become. Credit: Rick Guidice/NASA.

The Biomedical Transition: Shifting the Curves

You would think that technologies like CRISPR already take us a long way toward the modification of the human genome, but the way ahead is challenging indeed as we go from treating single diseases like cystic fibrosis to modifying complex traits of intelligence or longevity. It’s the difference between single-gene engineering and dealing with hundreds of genes and their interactions over time and changing environments. Thus Nikhil Rao (University of Florida), whose contribution to Stellaris explores the outcomes we want to achieve as we go transhuman.

No easy matter, this, for as Rao puts it:

Ultimately, most positive traits in humans are emergent functions of genes, environment, our interactions, and time. While gene manipulation and nanotechnology may modify these processes, potentially eliminating negative traits, they will likely not change the fact that human traits are ultimately distributed along a series of bell curves, even as science shifts the shape of those curves.

Shifting those curves will involve adjustments to the human immune function, mild immunodeficiency being surprisingly common. We might see accelerated evolution in Earth-based pathogens that have been unwittingly carried with us onto a worldship, for example. A seasonal allergy is an example of something that triggers inflammation and destruction of the body’s own tissues as a response to pollen, bacteria or viruses. Genetic engineering may eventually produce altered immune systems to cope with deadly reactions.

If you watch shows like The Expanse, you’ll see one visualization of changes to the human form resulting from lower levels of gravity, as in the example of the ‘Belters’ who live far from a planetary surface. Candidate planets for future settlement beyond Sol will demand body adjustments to cope with blood circulation and connective tissue issues, perhaps ruling out higher-gravity worlds. To the extent we can engineer for it, we may keep the example of Earth cultures in mind, says Rao. The short-stature, thick-torso Inuit are an adaptation to issues of heat dissipation and retention. Contrast them with “the long and lanky Masai of the hot, dry savannah.” Over time, we can expect adaptive evolution, or engineer for it in advance.

Meanwhile, life extension continues to be explored, with cellular repair mechanisms running headlong into the threats of toxins or radiation on a space voyage. Direct intervention to prevent gene mutation through gene editing may strengthen our protective systems, as could tinkering with the monoclonal antibodies that can be used to rid the body of mutation. Perhaps nanomedicine will emerge to intervene against everything from cancer to dementia.

Rao also talks about forms of cryonic storage, which has been in the interstellar voyage conversation for decades. Here we have the kind of suspended animation science fiction has long advocated as a solution to long voyages (and the plot problems they introduce into a story). He sees few advances in true cryonics but leans toward hibernation as a solution. After all, we know that animals can manage it, so it is biologically feasible and perhaps enhanceable through gene editing. Hibernation also has “clear endogenous (hormone and blood protein) triggers for induction and exit,” and offers the advantage of dramatically slowing metabolic processes to delay waste accumulation and cell damage (lower rates of cellular turnover).

Image: A Bussard ramjet in flight, as imagined for ESA’s Innovative Technologies from Science Fiction project. Credit: ESA/Manchu.

Here Rao echoes the working group in the idea of crew shifts:

Hibernation could reduce caloric needs by up to ninety percent based on animal models and produce up to a ninety-percent lengthening of lifespan at the theoretical high end. Simply stated, a month of lifespan is earned for every year of hibernation. Ten individuals in hibernation would strain life-support systems about as much as one individual active and awake. If every individual spent one year as crew and nine in hibernation during the journey to Alpha Centauri, that 150-year journey suddenly becomes a fifteen-year journey, which is far more doable within a single crew’s lifespan.

Rao is a psychiatrist specializing in critically and chronically ill children, a perspective that reminds us that shipboard and colony life in a strange new environment will stress the human personality over perhaps multigenerational timescales. He offers no easy solutions, but rather falls back on the persistence of older traits amidst whatever bioengineering we are able to pull off. He sees humans as capable of long-lasting cooperative networks and the kind of reciprocal altruism that took our species out of Africa, creating dreams of destinations as distant as the stars. Along the way, we’ll use our technological tools to adjust the human genome as needed.

Imagining the Mission

Although generally unmodified, I now wear glasses, so it could be argued, as editor and contributor Les Johnson does in Stellaris, that I am partly cybernetic.

I doubt many Centauri Dreams readers have trouble envisioning or accepting some physical changes to the human form — some noticeable, some not — or even machine/human interfaces that internalize digital technologies and offer access to information. But I think many in the general public would need to think twice about the fact that an insulin pump for diabetics, or an artificial heart, takes us into cyborg territory even today. We’re well on our way, in other words, to the kind of implants that may one day be common among deep space crews.

Transhumanism has been explored by many a science fiction writer, and I think immediately of David Brin’s ‘uplifted’ dolphins and chimpanzees as an example of what future technologies might allow. Johnson mentions bioengineered super-abilities in Timothy Zahn’s novels, or Nancy Kress’ explorations of humans that tech allows to ‘turn off’ sleep. I also think back to the four stories that went into James Blish’s The Seedling Stars (1957), where humans alter themselves to fit alien environments, already a well established trope in science fiction.

Blish referred to adapting the human form to an alien environment as ‘pantropy.’ Such adaptations can become extreme indeed: In the wonderful “Surface Tension,” an original human crew seeds a water world with new humans that are virtually microscopic and released into fresh water ponds. I also think back to Frederick Pohl’s Man Plus, which copped the Nebula for best novel in 1976. Here a cyborg is vividly adapted to handle the rigors of the Martian surface as a way of setting up a future colony on the planet. The transformation is grim as the protagonist loses his links with humanity on Earth but explores his new identity on Mars.

Johnson’s entry in Stellaris posits an extension of the issue. If our propulsion technologies still demand centuries to get to the stars, can we overcome the problem by sending human embryos that can be activated upon arrival to form a colony? The issues are vexing: Who raises the infants? In “Nanny,” Johnson writes of a starship that contains a crew that alternates in and out of cryostorage to maintain the ship and is intended to raise the first human generation born on the new world, but a catastrophe aboard the ship alters the plan.

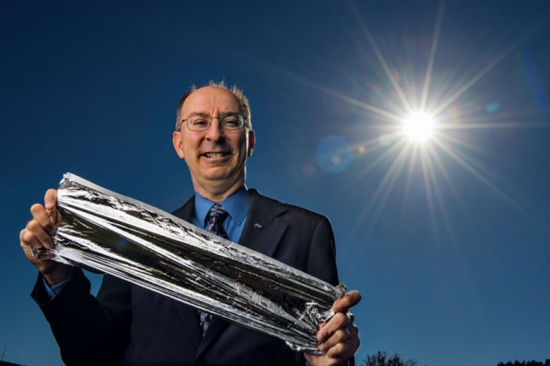

Image: Les Johnson, shown here with a sample of solar sail material that may one day be used to send a spacecraft deep into the outer system using only the pressure of sunlight for propulsion.

Are there other kinds of nannies that can raise children? The child whose voice introduces the tale seems to have few problems with hers:

Yesterday was Birthday One and we had a big party. Nanny said the day the first group of us were born was the happiest in memory. Thirteen Earth-years ago, the first fifty of us were removed from the artificial wombs and put in Nanny’s care. Fifty. I cannot even begin to imagine what it was like shepherding fifty babies, and then toddlers, around the house. But then I remembered that eight of the first group died, leaving just forty-two. Nanny doesn’t like to talk about that and has never told us exactly what happened to them.

I won’t either — no spoilers here — but how humans fit into the loop of automated systems is very much on Johnson’s mind in this cunning tale. An expert in deep space propulsion with extensive experience in solar sails (he is principal investigator for a mission we’ve discussed here, Near-Earth Asteroid Scout, as well as the much more ambitious Solar Cruiser), Johnson is an author and editor who sees abundant scope for humans as we populate first the Solar System and then nearby stars, beings who, “no matter their form, will be much like us.”

Thinking of biological beings traveling among the stars is pure bullshit… The members of a mission like this will in the worst case be brains in vats controlling robot avatars… Or ideally old biological brains that already did the moravec transfer before starting the trip, being then 100% digital conscious!

We should remember it takes a long time before mammals speciate. Humans remain one species despite tens of thousands of years of populations being islated from each other. Superficial physical changes have occurred, but no speciation.

Genetic engineering might induce speciation, but if so, it have to be extremely extensive. That alone would require computer modelling well beyond anything we can currently envisage. In sci-fi, invariably a person changes somatically after being given some initiator that changes the DNA. In practice, this would kill the individual very quickly as a DNA poison. Real evolution takes a lot of trial and error of small changes that accumulate. You can get populations that act like separate species as they won’t interbreed, but that is unusual. Humans were able to interbreed with Neanderthals, indicating that even though they are considered a separate species, fertile offspring were produced leaving us with a legacy of Neanderthal genes.

Technology enhancement seems much more likely to me. The examples of pacemakers and insulin pumps, as well as prothetics like spectacles is very relevant. Artificial heart pumps, prosthetic limbs, artificial joints, computer chip retinas, and eventually neural laces (very Clarke’s “braincap”) seem like the path we are going. These can be designed and manufactured and rapidly upgraded on a timeframe that vastly exceeds natural evolution, and probably even artificial evolution.

John Varley’s characters with body force shields and a lung replaced with an O2 supply allowing them to live on airless worlds is one path to take using prosthetics and technology. The other is mind transplant into artificial bodies, such as Sawyer’s Mindscan . Just transmitting minds into human bodies is the approach Richard Morgan uses in his Takeshi Kovacs novels.

However, unless artificial minds prove impossible to create, then almost all the problems of moving meat slabs around teh solar system and to the stars disappears if we can send robots. They can take a huge variety of forms from humanoid to almost anything one can imagine. They need no environmental systems, articial bispheres, or technology to mimic acceptable environmental conditions. Their design is far easier than using the declaritive gene engineering approach to modify humans. They can be made in situ and avoid teh need for robot nannies of human seedships. They can tolerate huge accelerations, and can switch off of reduce clock speed while in transit. In situ manufacture can outpace any human reproductive cycle ensuring that they become the dominant agents in any environment, whilst humans, even modified ones, can only live in a subset of possible machine environments.

“In sci-fi, invariably a person changes somatically after being given some initiator that changes the DNA. In practice, this would kill the individual very quickly as a DNA poison. ”

Not at all certain what you mean by this; in science fiction movies, of course, the (protagonist?) Injects him or herself with some kind of vile of liquid or what have you, and immediately undergo some type of stupendous transformation into whatever they transform into. It’s the same thing as in all the zombie movies-the person is bit and within maybe 1/4 of a minute or so the individual is miraculously transformed into a fiend. Never mind the fact that most viruses and/or bacteriums or what have you require a finite amount of time to act upon the body to enact whatever changes they are going to undergo. The point in fact is that it would be a boring movie if it took two or three days to enact any kind of transformation.

All that aside, there appears to be reason to think that it may be possible to systematically transform the central nucleus of the cell to permit whatever changes you wish to enact. Right now you can go to many websites on the Internet and find people who were investigating the aging process and that appears to require some degree of manipulation of the genetic code. My rule of thumb is that, within reason, any change that can be done can be undone if need be. So I’m not at all certain that cannot enact permanent DNA changes if need be in the event of various environmental conditions that would be encountered on any kind of extended spaceflight. The only question could be whether or not it could be done within a reasonable amount of time. That’s my take on the matter anyway.

Contray to this I give you just off the top of my head:

The Quaternmass Experiment

First Man into Space

The Titan

“The Quaternmass Experiment

First Man into Space

The Titan”

sorry, how does these movies counter what i say ?

They all have slow transformations over days and even weeks. Obviously this is still compressed into the viewing time of the medium.

I appreciate your reply (I really, truly do) but I believe you might’ve missed the point of my reply. In the case of zombies you absolutely MUST have a rapid transformation into the zombie creature simply because the fact that the whole purpose of zombie movies is to spread a disease and DO IT WITH EXTREME RAPIDITY.

I mean can you imagine a zombie outbreak in which it takes days and days and days for the population of zombies to reach a threatening critical mass? If it took days for somebody to transform themselves into of zombie, the military and police could easily respond and stymie any potential pandemic. And then where would you be with regards to the movie audience? In this particular movie genre you must have a rapid spread of the disease are otherwise nothing thrilling takes place.

I see where you are coming from. However, transformations are not just infectious zombies. In the case of The Titan it is a slow transformation to adapt to the Titanian moon environment. In the The Quatermass Experiment the astronaut slowly changes to become the alien organism that infected his body in the spaceship. No further infections are implied in both cases. My mistake in my original comment was to use “invariably”, because on reflection, there are a number of movies where the transformation is slow, rather than fast.

Having said all that, I think your argument is wrong. Just suppose there was a 1-2 week asymptomless state after infection before the infected could be recognized by the authorities. There may even be permanently asymptomless carriers, like Typhoid Mary. In both cases, the authorities could not stop the infection (just as the Covid-19 disease is proving in the US!). What if the symptoms even felt desirable so that people wanted to become infected, like having steroid injections?

A 1 – 2 week a symptom less state after infection wouldn’t change the course of events. I mean think about it – this isn’t just a question of typhoid Mary where individuals get sick and you have a question of who and where the infection came from. You have a zombie infection where people act like rabid dogs and attack people, openly chowing down on them like they are in all banquet buffet !

I kinda think that once you see a guy chewing on another guy in broad daylight you know you got more than just a problem concerning an upset stomach – LOL ! The fact that the disease in this particular case would be so extreme in way it presented itself would be a probably a strong clue that you’re probably dealing with something than just an ordinary sickness!

Yes I can see that symptoms that felt desirable could be desired by those who got infected, but those who were the victim of the infected would not feel quite so blissful as they found themselves being chewed upon by the rabid zombie…!

It’s entirely appropriate that an image of an O’Neil colony always makes me think of the Gundam series, where they were the setting of much of the action. One of the central ideas of the series was the emergence of a New Type of humanity, although the original writer imagined it happening on its own, without preplanned changes, because of the effect of humans living in an environment unlike any on Earth.

Also, the idea of robots raising children seems to be very much in the zeitgeist at the moment – I’ve seen 2 or 3 movies coming out with some variation of that.

When thinking of Transhumanism, I often try to consider the Minimum You. What minimum amounts of memory, skill set, fundamental functionality, and other such ‘data’ that resides in the brain is essential to the You that is desired? So now we tack on minimum sensors, mobility function, and ‘structure’ that allows the locomotion, data gathering, and overall ‘sense of the physical being’ (if physicality is required). How can all that be optimized for a journey, destination, co-mingling with other entities/ systems, and/or future existence? Perhaps something more modular, inter-changeable, and upgradable. But of course that brings is back to the Minimum You. (which seems like a great premise for a short story – where one is trapped and needs to escape/survive but can’t take all of ‘it’ with them – what to discard/ keep with a given level of bio-alteration tech)

So there is the expectation that our descendants wiill be beings who, “no matter their form, will be much like us.” Possibly. Even as we glance back at those who came before us…

From about two million years ago to 117,000 years ago our ancestors, Homo erectus were around, and even had substantial overlap with us: we’ve been around for 300,000 years, from which three more orders of magnitude gets us to a more remote progenitor, now “extinct”, the ancestor of the few extant lungfish and all land animals.

300,000 years from now, will our descendants look back upon us as we look at Homo erectus? And later descendants, like lungfish? That is if by then they have not transitioned to post-biologic machines (Matrioshka brains, maybe?)

I suspect that there will be a massive compression of time between post human descendants and H. sapiens, comparable to us and H. erectus.Even without technology, environmental differences in colonies will accelerate evolution. Technology might compress that down to millennia in teh genome, and centuries with prosthetics.

Human evolution hasalready speeded up.

Becky Chambers’ novel To Be Taught, if Fortunate describes characters, on a decades long exploration of a remote star system, who under go transformation to adapt them to each planet. A great tale. I recommend all of her books – check them out.

Some ideas here are very ethically problematic, so before they can be implemented Homo Sapience should invent the new ethical rules as replacement for our current ethical and moral rules.

Till now all experience with ethic/moral rules modification to make the New Super Man was very frightening: fascism, communism – are examples of this “experiments” for Homo Sapience modification, improvement.

For example mr. Johnson ideas (space grown kids) are ethically very doubtful even at first sight…

The lessons of history can be misleading, but unfortunately, they are the only ones we have.

Our attempts to predict human expansion into deep space must rely on examples from our own maritime experience as a species. But we must make the distinction between the spread of early Man across the planet, on foot, and the expansion of fleets of ships sponsored by organized communities. The former is just the natural diffusion of any plant or animal across a landscape. The latter is an organized activity planned and carried out by civilized communities using technologies designed for that purpose.

The island-hopping colonization of the Pacific Basin by sailing canoes is the first, and most appropriate, model that comes to mind when trying to understand our future exploration of space. However, the social and economic conditions that motivated these great seamen and initiated these migrations are unique in both space and time. We can’t count on them happening again, or too often. This most magnificent achievement of Neolithic societies has already been studied extensively by futurists seeking to understand our potential diaspora across the Galaxy, but there are other examples, perhaps more appropriate, as well.

The ancient Phoenicians and Greeks traded extensively throughout the Mediterranean, and founded many colonies on its shores, some as far away as the Pillars of Hercules, but neither their maritime technology nor social organization made possible a truly global expansion. The Vikings were great blue-water sailors, but their most significant voyages were along the river systems of Eastern Europe. As Western cultural chauvinists, we often tend to celebrate the European Renaissance colonial expansion into Africa, Asia and the New World, but this also occurred simultaneously with the great voyages of Arab and Chinese mariners in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific.

It might be instructive to contrast the European and Chinese efforts, since one clearly expanded till it encompassed the entire planet, while the other declined, in spite of decided advantages in technology, funding and organization. The Chinese lug rig could sail into the wind, and their ships were equipped with the magnetic compass and the centerline rudder. They were clearly superior to anything in the west during the Middle Ages. But the Chinese merchant class preferred instead to consolidate their stranglehold on domestic trade and discouraged overseas commerce. As for the Arabs, their loss of the Indian Ocean trade route monopoly and the Ottoman Conquest finished their maritime ambitions forever. In Europe, capitalism and a rising aggressive middle class saw ocean trade as a way of working around their stagnant and decadent land-holding aristocracy. Even so, European traders were not so much interested in new colonies or free trade, but in quick riches from slaves, Aztec silver, Inca gold and drugs. Yes, drugs. The European colonies were not exploited for their abundant new food crops, but for sugar cane, tea, coffee, cocoa, and tobacco. Rounding out these cargoes were spices, furs, and other highly-valued, but essentially non-essential, luxury goods. The only truly valuable product of the New World was hardwoods, hemp and naval stores, in order to build more ships and the navies to protect them. And as we all learned in primary school, Columbus didn’t come here looking for new lands, or to save souls for Jesus, he came seeking to circumvent Arab control of the Indian Ocean trade routes to India and the Far East.

It may be tempting to project our own entrepreneurial fantasies and misguided cultural prejudices onto the starship sailors of future centuries, but lets be realistic. Voyaging is a potentially profitable, but certainly risky business. And it is hard to see what products of value are to be found around other stars that are not readily available around our own. To a species capable of interstellar travel, the agricultural or mineral resources of other systems can easily be synthesized anywhere there is a source of ice, rock and sunlight. Deep space may be irresitable to the scientist, but it will quickly lose the interest of the capitalist. As for all those lofty goals of political and religious freedom, well…that may motivate the sailors, but it won’t pay for the passage

There is one valuable commodity, the selected organisms as products of evolution that has operated on near infinite space of possibilities. Life on Earth has explored an infinitessimal fraction of the possible forms it could take. Other living worlds will have explored different avenues, both with our biology, and with their own. Evolution has selected viable organisms that would be vastly expensive to discover by selective and computational means. Today all we can do is either create better enzymes by iterative design and test, or [semi-]randomly alter genomes of rapidly reproducing organisms to discover interesting viable ones with new traits. These experiments can barely scratch the surface of possibilities, and certainly not simulate biospheres.

Therefore, I would argue, that living exoplanets might well have something valuable that is worth the expense of trade. In movie fiction, Weyland-Yutani Corp. were clearly very keen to retrieve an example of the Alien for their bioweapons division, an organism that had a very different biology to terrestrial like.

I have to concede you are absolutely right.

Alien biochemistry, whether extrasolar or from our own solar system, will be the ultimate prize; not just for science, but for capital as well.

“My precious…”

Comparison of the maritime quests to space explorations is superficially possible, until one gets down to the brass tacks. Almost every island is inhabitable; the ocean itself contains edibles, some of which have been known to jump into seafaring craft; potable water falls out of the sky; a breathable atmosphere is everywhere. Just about every point of shoreline can be reached well within a human lifetime.

Tom Murphy is an astrophysicist who works for NASA to study moon-earth interactions by determining the distance to the moon to centimeter precision by laser interferometry with reflectors left on the moon by the Apollo missions. He is also a professor on the Physics faculty an University of California, San Diego. He has written about the topic Why Not Space?

I realize the website is called “Centauri Dreams,” not project, plan, endeavor etc. So leaps of the imagination are to be encouraged. But am I the only one a little jaded with these pie in the sky ideas? I recall O’Neill Colonies were all the rage back in the mid 1970s. Never happened. Same with moon colonies, manned exploration of Mars, etc. None of these ideas ever take into account politics, budgets, climate change, overpopulation, or mass migration. Of course some science fiction writers consider these factors, and their writing tends to be more credible. Other writers just place their stories so far in the future they don’t have to explain how we get from here to there. I’ll admit I’m sort of a hypocrite though, because I keep reading the articles even if I have my doubts.

Back in the optimistic, high-tech 1960s, rapid development of space travel was envisaged. Arthur C Clarke thought it would follow the path of teh aviation industry, about 50 years from Wright brothers inception to comfortable jet airliners. As with flying cars and jet packs, that was a future that was largely stillborn. However, the New Space companies are now succeeding in developing lower cost access to space launch vehicles and giving government programs a run for their money. Clarke once compared the ill-fated R101 (government designed and built) airship that crashed on its maiden flight to the privately built R100 that was successful. With aircraft, airframe private builders builders have ruled the roost quite successfully since inception, with government keeping out of the business other than to specify requirement for their, mostly military, needs. Governments did R&D and primed the epump for business development. Space flight has not followed that path, with satellites being the only major business opportunity. Human spaceflight has remained a government funded and developed endeavor. Without a business model, they cannot follow the growth pattern of commercial businesses.

As for flying cars, person-carrying taxi drones seem to be imminent. However, I don’t think flying cars are good idea for a variety of reasons, safety and reliability issues being a major one. Computers seem to have proven a far better business with so many applications, with communications reducing the need for physical travel. The current pandemic is demonstrating how much more physical presence could be reduced if we threw off our conservative practices.

In 1951, Clarke wrote “Holiday on the Moon” for a “young ladies” magazine. It, like the tourist scenario of “A Fall of Moondust” sadly remains a lost future that I would have dearly loved to have seen and been part of.

P.S. I recall “Man Plus” by Frederik Pohl. This was a dystopian novel about an astronaut altered by science and technology so he could survive on Mars without a spacesuit. Needless to say all the experiments and enhancements he endured were a nightmare.

“Man Plus” sounds like a good read

Yes, I recommend it. It’s a chilling tale and extremely realistic.

Fabulous piece, Paul, thank you.

Reading your post I wondered if we might experience ‘bifurcation’ in a different way and from an unexpected direction? First let me say that terms like ‘speciation’ and ‘bifurcation’, in the traditional definitions, could be inadequate tools.

What I mean: aren’t we seeing a kind of ‘division’ now, on planet Earth? So much separates those of us so incredibly lucky to exist in the ‘first world’ (another difficult term!) show measurable delta in many characteristics when viewed from those born with much less opportunity and mostly in parts of the world we usually term ‘third world’.

Perhaps most obvious but poorly understood is the worldview humans naturally build; more measurable elements include life span, disease, and similar disparities.

It’s an incomplete argument to be sure, one that springs from considering non-traditional routes to separate sub-species. And the question might be seen as perhaps guilt-motivated, written from a place and time where some of us have access to the very best humanity has achieved to date.

Somewhere there’s a kernel worth investigating.

Yes, I agree with you, Michael, about the inadequacy of terms like speciation and bifurcation in this context.

Exactly, who would want to live for a thousand years in a slum.

Any slum on Earth has a view of Sun and blue sky, comfortable winds bearing limitless oxygen, often water that could be purified with minimal effort, enough food to sustain life by definition, of varied natural origins, and hope for migration to many places. Compare these to most plausible plans for habitats in space or on other planets…

Slums are a code word for avoidable human inhumanity – food insecurity, fear of homelessness, fear of crime, fear of being cast as a criminal for the faintest human foible. Yet even the wealthy live in needless fear today. If we dream a story in which those things can be defeated, we can dream a story where the poorest slum is a joyous and efficient expression of our one sacred Homeworld, a place of matchless wisdom, science, and faith, an object of pilgrimage from all the peoples of the infinite cosmos.

It is far harder to write of Paradise than Inferno, and the result generally of lower merit, but even crude utopias are the novels that change the world.

Well said. The real migration is not into space, it is to a world without limitation; energy, space, time, potential, opportunity. That’s been the dream since the first voyage to explore new lands. Clarke’s 2001 was in answer to the collapse of that dream for an overpopulated world on the verge of anihilation. Even for those living on earth, the expansion of humanity into space means living in a much different world.

I think you are talking about slums in the USA, try looking beyond the idelic artificial world view of western ideals. The real world is much worst, take it from one who has seen and felt the problems of the entrapped poor.

I’m afraid we are really limiting ourselves on what could happen in the not to distant future… Why and what would support an otherworldly experience. Humans have always enjoyed a sense of adventure and the greatest nonviolent version of this is exploration. We can imagine and now create via simulations this but exploration and the question what will be found over the next mountain is the heart and sole of man. We still have huge mysteries right here in our solar system, the gas giants may have life in forms beyond our comprehension. What if Planet 9 is a interstellar gateway? This is what could take this well beyond anything imagined by us. Perhaps this great urge will be rewarded when we reach the outstretched hand of God…

Along with sleep shift rotation they could after say 25 years have you go into hibernation and re-sleeved with a new body, there will be plenty of time to heal while you sleep your sleep cycle out.

Since there seem to be far more subsurface oceans than terrestrial planets in this Solar System, the real direction of genetic engineering or transhumanism might be to convert terrestrial humans into something resembling whales: hydrodynamic shapes with enough thermal mass to survive in a cold, dark ocean.

While our surveys of alien solar systems are biased due to the limits of our technology, the adaptations we might need to make for our future colonizers might be equally alien – high gravity “Super Earths” will certainly need a very different set of adaptations, for example. Living in solar systems with massive gas giant planets in close proximity to the sun might also need adaptations for weird magnetic fields or radiation showers coming from the planets.

Really, speculation about transhuman or post human evolution is based on far too little information to be more than handwaving at this point.

Cetacean evolution is indeed a fascinating subject, as is evolution in general, perhaps because it offers a conceptual handle on evolutionary time. Incidentally the biggest animals to live on the planet earth are alive today: the whales. Fish were limited in gas exchange by an less efficient liquid medium and gills. Land animals are limited in size by gravity which is partly compensated for by buoyancy in aquatic environment.

Perhaps a hard-plated exterior may be a more useful adaptation to interstellar travel than a insulating fat layer alone or in conjunction with the plates.

Dinosaurs in SPAAACE! ;)

Humans will travel and occupy the solar system eventually (if we survive long enough as an advanced civilization) but the stars and exoplanets will only be visited by our machines (again if we survive long enough to build them). I’m looking at the ideas of genetic manipulation of humans and seeing insurmountable limits if we are to remain organic. It won’t take us to the stars. I don’t believe we will ever build world ships that will take thousands of years to reach nearby stars (if there are actually habitable planets that close to us). The writings of Kim Stanley Robinson are informative and realistic on these subjects. Many sci fi authors don’t even attempt to explain how we reached the stars. how their amazing star drives work etc. etc. I’m not pessimistic on these subjects. I think we have an amazing future in space, but inside our own solar system and only if we learn some humility and self control. Current world events don’t suggest that is happening unfortunately.

“The Solar System” is a big place. Recall the Oort cloud is over 3 light years in radius. I imagine other clouds may overlap it that we have no clue about. Oort cloud objects are packed with the basic elements of life (“CHON”), and at least some “asteroid” trace materials are present. I checked Wikipedia – the estimate they cite is down to just 5 times the mass of the Earth of this stuff, much less than it used to be, but think of how little of the Earth is usable for biomass! If you can build fusion plants or harpoon a passing object with an absurdly long tether you can let out to generate power, there is a potential for an ecosystem vastly larger than any we’ve known. Alright, maybe you have to reengineer DNA as PNA and replace most of the cell’s ATP with some phosphate-free counterpart to creatine phosphate (we are not even confident of the phosphorus supply on Earth right now). To a far future society that still might be a Herculean task. But there’s no lasting reason why a sane and surviving human race, if it existed, couldn’t spread out in dribs and drabs between dwarf planets like Eris and Sedna, Oort cloud objects, rogue planets, and objects associated with other star systems. The cosmos only seems empty and distant because we haven’t built all the telescopes we want.

A very entertaining post, Paul. Beautifully opened with Shakespeare’s Ariel. I have often mixed views about including references to fictional works in discussions on what are at their core scientific subjects. But the topic is so speculative, fiction fits in well. You really let rip with the references. Haha. In your element. Nice.

Thanks, John. Sometimes it’s just irresistible!

Thoughts about human speciation and the adaptations needed for interstellar travel brings into focus much sharper ethical problems and parallels between civilizational and personal maturity. The endeavor of interstellar colonization could lead to extreme escalation of tensions which are present in modern society but were not perceived in the age of Columbus.

In the past, we just sailed, conquered and settled. And it was done by those who were able to do it, no hesitations. No doubt there was blood, but we all now see the effect. Now, even in the absence of sentient life at destination, we would think – who of the equal humanity should represent us? Then, is the equality implicitly abolished by the fact that worldship population is million times smaller than Earth’s and biased by the needed qualification of personnel? What would be a reaction to a private company stating something that sounds like “to hell with you mired in ethics (and bureaucracy), we just fly because we can, and down below you’ll never go”? And many other questions.

This kind of problems was illustrated very well in Three Body Problem, and their magnitude indicates civilizational immaturity. In example, with it the (essentially) same situation is seen very different if it is a forced reaction, or a voluntary act. If a new branch of humanity is created in response to a challenge where the options are either adapt or go extinct, it is the act of heroism. But the very same endeavor made by some group of fluorishing society, even with the best intentions, could well be seen as treachery.

The Columbus approach is no longer valid. But should we enter interstellar age without constructively solving these issues?

I think that while it is a wide belief that humanity achieved or is achieving ethical maturity in XX and XXI century, we are in fact very far from that. Yes, we departed from primeval state, but it is much more like early adolescence, when rapid development causes contradictions to rise and come into clash with each other, but the full picture of fundamental contradictions in ethics of sentient species is not yet recognized. The inflammation of ethical paradoxes, after which comes the awareness, the reconciliation and the transition to a higher level where it is not possible, and then the ethical maturity…or the downfall of civilization in any of these steps.

A rough adolescence, as showed first experiments like the mentioned fascism or communism. But the balance of pessimism and optimism here is really sensitive. Our first experience was so bad that we entered overcompensation which is tabooing further experiments and offers no truly constructive or transcending solutions. But while we surely don’t want to repeat these mistakes, we have not destroyed ourselves or crumbled back into stone age. The experience was no doubt traumatic, but think of civilizations somewhere there in the sky which really broke bad!

From here, there is a step even further, to say “we will go and reach the stars when we are ready for it”. As it was said on Centauri Dreams before, “If we knew for sure that the Sun would explode on Jan.1, 2100, we could start building interstellar ships today and had a chance for success”. In the absence of external stimuli, it may be much harder, but with more chances for the ethical maturing – which is a good thing indeed.

Please consider “The Architects of Fear” as part of your discussion. KH

Why? You introduced it so you make the case.

The Dreams of Space blog has a very recent post on the 1965 book Beyond Tomorrow: The Next 50 Years in Space, authored by Dandridge M. Cole and featuring many of the great pieces of artwork by Roy G. Scarfo:

http://dreamsofspace.blogspot.com/2020/09/beyond-tomorrow-next-50-years-in-space.html

It also has a reference link before the art display for a 2012 article on Cole from Centauri Dreams:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2012/05/14/remembering-dandridge-cole/