When the question of technosignatures at Alpha Centauri came up at the recent Breakthrough Discuss conference, the natural response was to question the likelihood of a civilization emerging around the nearest stars to our own. We kicked that around in Alpha Centauri and the Search for Technosignatures, focusing on ideas presented by Brian Lacki (UC-Berkeley) at the meeting. But as we saw in that discussion, we don’t have to assume that abiogenesis has to occur in order to find a technosignature around any particular star.

Ask Jason Wright (Penn State) and colleagues Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback and Adam Frank (University of Rochester) as well as Caleb Scharf (Columbia University), whose analysis of galaxies in transition has now produced a fine visual aid. Described in a short paper in Research Notes of the AAS, the simulation makes a major point: If civilizations last long enough to produce star-crossing technologies, then technosignatures may be widespread, found in venues across the galaxy.

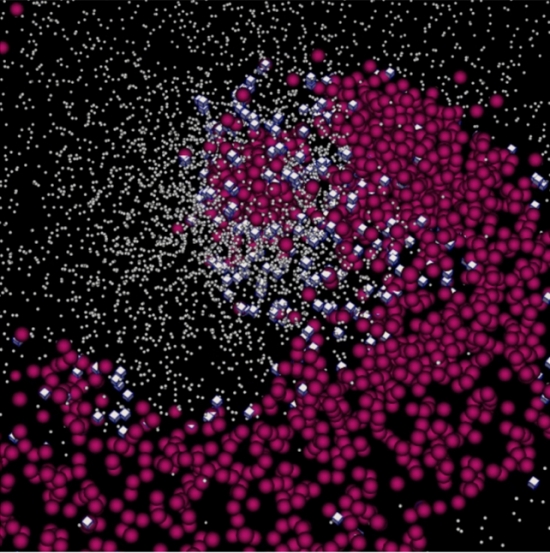

The simulation depicts the expansion of a technological civilization through the Milky Way, created along lines previously described in the literature by the authors (citation below). What we are looking at is the transition between a Kardashev Type II civilization (here defined as a species using its technology in a significant fraction of the space around the host star), and a Type III, which has spread throughout the galaxy. Wright has argued in earlier work that, contra Sagan and others, this might be a fast process considering the motions of stars themselves, which would overcome the inertia of slower growing settlements and boost expansion rates.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: A snapshot of the animation showing the settlement of the galaxy. White points are unsettled stars, magenta spheres are settled stars, and white cubes represent a settlement ship in transit. The spiral structure is due to galactic shear as the settlement wave expands. The full, low-resolution video is available in the HTML version of this research note, and a high resolution version can be found archived at ScholarSphere (see footnote 7). Credit: Wright et al.

And here is the animation, also available at https://youtu.be/hNMgtRf0GOg.

Issues like starship capabilities and the lifetime of colonies come into play, but the striking thing is how fast galactic settlement occurs and how the motions of stars factor into the settlement wave. Naturally, the parameters are everything, and they’re interesting:

- Ships are launched no more frequently (from both the home system and all settlements) than every 0.1 Myr — every 100,000 years;

- Technology persists in a given settlement for 100 million years before dying out;

- Ship range is roughly 3 parsecs, on the order of 10 light years.

- Ship speeds are on the order of 10 kilometers per second; in other words, Voyager-class speeds. “We have chosen,” the authors say, “ship parameters at the very conservative end of the range that allows for a transition to Type iii.”

All told, the simulation covers 1 billion years, and about it, the authors say that:

…it shows how rapidly expansion occurs once the settlement front reaches the galactic bulge and center. The speed of the settlement front depends strongly on the ratio of the maximum ship range to the average stellar separation. Here, we deliberately set this ratio to near unity at the stellar density of the first settlement, so the time constant on the settlement growth starts out small but positive. Eventually, the inward-moving part of the front encounters exponentially increasing stellar densities and accelerates, while the outward-moving part stalls in the rarer parts of the galaxy. Note that at around 0:33 a halo star becomes settled, and at 0:35 it settles a disk star near the top of the movie and far from the other settlements. This creates a second settlement front that merges with the first…

It comes as no surprise that the central regions of galaxies, thick with stars, are places that favor interstellar migration. Can a technological culture survive against ambient conditions in a galactic bulge? If so, these regions are logical SETI targets, and perhaps the most likely to yield a technosignature. The idea has synergy with other observations we are already interested in making, as for example studies of the supermassive black hole at galactic center.

So even slow — very slow — ships will fill a galaxy.

The paper is Wright et al., “The Dynamics of the Transition from Kardashev Type II to Type III Galaxies Favor Technosignature Searches in the Central Regions of Galaxies,” Research Notes of the AAS Vol. 5, No. 6 (June 2021). Abstract. The 2019 paper is Carroll-Nellenback et al., “The Fermi Paradox and the Aurora Effect: Exo-civilization Settlement, Expansion, and Steady States,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 158, No. 3 (2019). Abstract. This earlier paper is a storehouse of references and insights into the likelihood of interstellar settlement and spread.

Oh good, Star Wars got it right. The Core will indeed be a nexus of galactic civilization.

Well, as did Foundation, which George Lucas so expertly and brilliantly took good ideas from and combined them with other bits of awesomeness to form his magnificent franchise.

Technosignatures may well be more prominent if you’re hunting for old civilizations in the galactic bulge, given the larger scale of such.

Isn’t the galactic core a rather “energetic” environment not conducive to stable planetary systems from various gravitation interactions hurling comets and stuff not to mention supernovae and gamma ray death stars. It’s the boring suburbs, like our neck of the woods, that foster stable evolution of life and presumably civilizations.

Sure, a tourist trip to the core would be nice, sort of like viewing an active volcano but no would like to to live there.

While your summation of the struggles with core systems re: feasible planetary life is reasonable, it’s important to remember that even a Type II civilization dwarfs our current ability to live in spaces around planets and stars. It’s quite reasonable to expect that a Type II-headed-to-type-III or type III civilization cares less about the habitability of a planet than simply using it for its resources – planetary living becomes a facet of where/to whom you are born rather than a pure necessity of a civilization.

And Type IV civilizations are unicorns that thrive on hydrogen between the stars and love surfing on gravitational waves. Sometimes, our assumptions far outstrip even the most stretched versions of reality as we know it.

Judging by your posting name, it would appear that you have taken offense at something I posted. Whatever it was, it was not aimed at anyone nor meant to demean any idea.

With such expansion lasting just 1 billion years and so many stars colonized, the obvious issue is the Fermi Question. Technosignatures should be everywhere we look unless the expansion has either not started or is in the early stages.

The glibness of saying that a starship is only launched no more frequently than every 100K years. Human civilization hasn’t been around for more than 12% of that time. Yet a civilization is either stable enough or able to rebuild every 100K years to launch a starship?

Complex life on Earth has at most be around for 1 by. Evolution constantly changes lifeforms. Why would we expect that to be different for alien species? Forget cultural changes, over that span of time the stars would be populated by many, many species, all with interstellar aspirations more applicable to a culturally and physically homogenous civilization with that goal.

The same applies to humanity if we assume this is a model for our future expansion. H. sapiens won’t be around for a million years, let alone a billion. Even if our future was a machine civilization, it wouldn’t be static, as it designed/evolved new forms and cultural ideas.

While expansion could be fast, like bacteria in a petri dish, once the galaxy is colonized, then what? Expansion stops, economic growth will tend towards zero, energy consumption might even decline as stars age and die, leaving the cooler, lower luminosity stars. The next stage would have to be intergalactic expansion. However, to use Asimov’s analogy that travels from star to star to find a new home when the sun dies is like hopping over to the next tree in a rainstorm hoping to stay dry after the current tree lets the rain through. The analogy applies to the universe of galaxies.

If it takes a billion years to colonize the galaxy, the average economic growth over that time is also close to zero. [start at 1 star, reach 1E11 stars over 1E9 years. Rate of growth ~ 1E-8 %/yr. This implies either a very static civilization despite its transition to a KIII civ, or that civilizations rise and fall and that the occasional one (10%) makes the trip to the next star.

I will admit to a failure of my imagination regarding this expansion. In many ways, I prefer the rapid expansion to fill the galaxy in a million years or less, possibly by an expansionist civilization that maintains some sort of cultural expansionist imperative and the technology to do so. Similarly, Von Neumann replicators could also fill the galaxy in that million-year time frame. I would argue that rapid colonizers would be more likely as they would have a first-mover advantage and suppress expansion by slow-moving civilizations.

This leads me to mostly dismiss the advantages of stellar movement. While it helps over a billion years, as the simulation indicates, it does not help over much shorter time frames. A billion years is 4 galactic revolutions. A million years is less than 2 degrees of a rotation. As we saw in a previous post on stars with close approaches to our solar system, it is really much more expedient to just strike out for the nearest stars rather than wait for any advantage of a close encounter.

I have yet to see a convincing argument why advanced civilizations would need to constantly expand like bacteria in a petri dish.

I could argue why human population should exceed 1 trillion people, but it seems what you mean by advanced civilizations is far more advanced then what humans have achieved. It seems humans living centuries ago, could correctly say the present human civilization is very advanced, but some important aspects of what one could call an advanced civilization has failed to occur.

And possible it may never happen for human beings. Or we have long lasting issues in which are sort of like Groundhog day. But idea of diversity seems to hold a lot of promise- Aliens might solve things we can not.

It seems if want call us presently advanced, it’s mostly technological- fly planes, have computers, etc. And in that regard, we can go a lot further- and maybe that is what one could called an advanced civilization. But other might think of advanced, roughly as “smarter”, such as have educational system which works, etc. And realm of politics seems like it’s stuck in the stone age- or possible worse. One could say we aren’t preserving our history- our past is bits and pieces. It could be if history was preserved, we might not “need” to keep repeating the same stupidity, over, and over again.

It seems we to know what advance civilization “looks like” before we could judge this. But stagnation, we have seen what that does. China’s history {what little we know of it] is one many lessons in this regard.

I think (advanced) civilizations need to expand because of the many sources of potential expiration of entire species. For all we know technical civilizations may be as rare as hen’s teeth; it seems unassailable that even if there were many they would vary greatly from one to the next. I am not sure whether it is a solipsistic vanity that we need to preserve our species and our creative production or it it perhaps a moral issue that we should strive to preserve and advance ANY culture that has arisen anywhere?

It seems more and more that the paradigm of colonization models and Great Filters is exhausting itself. There were many simulations which show one thing – once iterative colonization commences, Galaxy becomes thoroughly colonized on very short timescales, no matter of details. It requires unnatural tweaking and/or limiting to slow it down sufficiently. The same with Filters – they fail to explain complete and sure extinction of all civilization-bearing species. There is just no conceivable Great Filter of destructive kind that fits all. Mathematically speaking, since GF has to be universal and unforgiving, any model of it is disproved by construction of a single case which evades it.

While I was thinking about this strictness and it’s implications, I realized that the alternative could be formulated strictly as well. Somewhere between our stage and true iterative interstellar colonization there is a necessary transition in which _all_ civilizations leave or abandon all kinds of extensive development. All primary exponents – harnessed energy, occupied space, used matter – necessarily end somewhere between our current stage and the level of mature iterative colonization and/or massive astroengineering/Kardashev II+. They stop before building Dyson swarms and spreading through the Galaxy because the farther they go, the more favored becomes the non-extensive development or existence over the extensive one.

Does this mean we have no chance of detecting them? Absolutely no. With the means of solar gravitational lens, we can confirm the presence of another civilization like ours across the Galaxy, kiloparsecs away. It has enough sensitivity even for the case of Multiple Small Filters which explain rarity of civilizations but not what happens after they mature. The Great Turn has to be really close to prevent us from doing this, yet we don’t have a slightest hint of what it could be.

PS more about insufficiency of Filters. Humans are universal and omnivorous species. It’s reasonable to expect that many others are too, since these traits are building blocks of intelligence and they protect species from extinctions in their Stone Ages. And it is very hard to exterminate this kind of species once they’re gone global. We seem fragile in our high-tech environment, but humans can actually feed on carrion and endure extreme environmental fluctuations with just stone-age tech. In reality we have a potential to be no less hardy than crocodiles and cockroaches, the species that survived Chicxulub and endured more than a hundred million years. If another Chicxulub strikes in 2040, billions will die but many thousands will remain, and restart the new civilization no more than in several thousand years. The true Second Dawn is always faster than the first one because of remaining artifacts and information, from written books to solid state information. There’s two another points: first, even in the major extinction-scale event during the development of high-tech civilization, every piece of really useful information survives in multiple copies and forms. Second, once the civilization passes through tight population bottleneck, it is much easier to build the second attempt on renewable sources (like crude solar-thermal closed-cycle engines for electricity generation which seem insufficient for us but can readily could support a billion-strong civilization).

The cataclysm-type Great Filter could not guarantee the complete extinction even in one model-case, human civilization. And it has to explain much more – that no one survives. Even the lucky ones. Even those who have the pure luck combined with easier access to space and better motivation to colonize another stellar systems.

If we had just the luck of having two surely-habitable planets in the Solar System, which is not rare in the Galaxy, there would be permanent and highly authonomous colonies on another world by now, with relocation accessible to many. In this model, bio-compatibility issues can be bypassed due to disproval property of Universal GF; if another world has an abiotic oxygen atmosphere and buried carbonated, or biospheres are compatible due to repeated lithopanspermy (chunks of crusts flying between worlds acting as vaccines against pathogens), it’s enough. In this setting, by the second half of XXI century no one would say that we have all eggs in one basket. Any type of cataclysm which completely ravages one planet, be it a supervolcano, solar superflare or some kind of obscure internal failure mode of late Digital Age, leaves another planet intact. In case of a superflare, an unlucky conjunction is needed to bust networks on both worlds; in the latter case, the population on second world has a much better chance to learn on mistakes than it’s possible on the same globe.

If there is universal destructive Great Filter, it should have acted by then. We might say that since we cannot imagine anything natural or internal of this kind, it has to act further into future, but thought experiments show this is not the case – GF is running out of time.

I absolutely don’t believe in any extinction-type Great Filter. Except maybe for Inhibitors, but not really – again we can construct the case in which a civilization studies this possibility and behaves accordingly. And, why Inhibitors are so late? If we can see so much through solar gravilens, than they surely can see us now and before. And it would take much less effort to exterminate humans during Toba super-eruption, just like it’s easier to weed out cockroaches when they occupy just some corners and not every hole in the house. Late Inhibition is just uneconomical.

As another comment says just in this thread, “I have yet to see a convincing argument why advanced civilizations would need to constantly expand like bacteria in a petri dish.”

My question is how many decades do concepts such as the Alcubierre metric have to be studied in the mainstream literature before studies such as this make the natural and reasonable assumption that a very advanced technological civilization might have figured out how to make them practical and attain reasonable speeds of interstellar travel and migration instead of locking in pre-Alcubierre assumptions and extremely slow speeds such as 10km/s?

It’s not really a question of how long you study it. It’s a question of whether it works or not. Warp drives have the attention of modern physicists. If the physics is “real” and assuming steady technological progress, I would guess a warp drive spacecraft could be built in about 100 years. And if we can’t build it in 100 years, it’s probably because it can’t be done. If something that is theoretically possible is impossible to engineer, then in reality it’s impossible.

“Technology persists in a given settlement for 100 million years before dying out”

100MY does not seem reasonable at all to me. Just my opinion: probably 1k or 10k. Wonder what the percolation animation would look like under those conditions.

Given our current understanding of evolution (not to mention other factors such as climate change, stellar flares, etc) it’s probably unlikely that the species itself would survive for 100MY, never mind its technology.

That seems to be an undiscussed issue when talking about long-term galactic settlement. If (for example) modern-day humans start the process there are not modern-day humans at the end of the process, and not all of the descendents/various speciated branches may have the same mindset as the original colonists when it comes to the urge to spread throughout the galaxy. It seems just as likely that the colonization would peter out at some point.

On these early stages of exoplanet characterization, we are short of a good indicator of whether a one or two parsec ranging settler ship for interstellar society will be adequate for our own interstellar needs. To illustrate: suppose we need to go five or six parsecs to find planets that are worth the trouble. For example, in the case of the recently discussed Scholtz’s star, which skimmed by here 70,000 years ago, we know it was connected to a brown dwarf and it was a faint red dwarf itself. Given only this information, who would want to set out to explore and exploit that? Consider “that” an initial bargaining position.

Then what do local stars have to add at further distance? For us, it might be a terrestrial world where the surface pressure is 20 psi, +/- 20%, free oxygen a potential and an anti virus certificate.,, So these are things to look at to consider why such an expansion might take longer and/or be less attractive to others who have time to consider. The main advantage of a Kardeshev civilization scale for such discussions is that advancement up the scale makes them more and more observable. Beavers might regard our own Earthly civilization in some kindred way: Beavers that are really good at dams but don’t seem to have the big picture or understand what happens in the long run by overbuilding and hence being over-dependent on the result. If there were a way to examine a civilization’s capability for both advance and continuity…

This study of course has certain assumptions.

First of all it ssumes that advanced civilization would wish to expand to other solar systems. As previous discussions show, once you have the means to colonize other planets, you no longer have to. You already have the technology to sustain liveable habitats in space or transcended limitations of your own evolutionary biology.

Second of all a vast colonization like this leading to K2 civilization would require a coordinated effort that is simply impossible due to limitations of the speed of light. Now, we can imagine a civilization operating on vastly different time scales but again, it would be a civilization that has abandoned the biological imperatives and likely wouldn’t be interested in settling each world possible.

“It comes as no surprise that the central regions of galaxies, thick with stars, are places that favor interstellar migration.”

That’s a consequence of the very unlikely choice of parameters. Why a civilization in transition to KIII would restrict itself to such very slow speeds and small trip ranges that its expansion would be so tied to star distances and star motions around the galaxy?

Don’t we have proof that this model can’t be correct, since a ubiquitous occurrence of inhabited systems would, by necessity, leak detectable technological signatures. Unless, of course, we are the first or close to the first technological civilization that might be expected to go interstellar.

The three imperatives of molecular structures that took on machinery-like functions leading to biology are survival, growth and replication: this separated the more effective from those that didn’t quite cut the mustard; the latter were consigned to the dustbin of the past.

Every organism would expand not only through time but also through space until it reaches limiting conditions. Homo sapiens has defeated the constraining limits until now. We split from the chimpanzee lineage six million years ago, and as recently as three million years ago there were half a dozen or so hominin lineages. Homo sapiens is 300,000 years old, but all the other lineages are extinct, although those in our direct ancestry live on in us. The exit from Africa started 50,000+ years ago, but there is no difficulty distinguishing between Chinese and Scandinavian on physical and other characteristics.

Continued growth in space would now require exiting the earth’s gravity well and taking along products of the ecosystem (short term) or a sample of the ecosystem itself (long term).

And then there is the question of whether a Great Filter is ahead of us. An item of concern is resource and (fossil fuel) energy depletion. It remains to be seen whether a transition to alt-energy can be effected.

A civilization that proceeds to colonize the galaxy would be past the (last?) Great Filter; and it would not remain monolithic for long, but would diversify even to the exient of speciation (inability to breed across lines of differentiation).

And also it may abort the emergence of other civilizations: an alien civilization arriving on Earth just after the dinosaur extinction would have encountered our ancestors, little shrew-like mammals. The aliens would likely have had no qualms about taking the planet for their own use, aborting the radiation of the varied mammalian orders.

The expansion could result in a veritable galaxy of Babel.

I do not agree with your “3 imperatives” assumptions.

First of all life has no “imperatives” as we know from Darwinian natural selection. There is no directed plan, no objective long purpose and no main goal in evolutionary terms. Expand and grow are not there either. They might be very typical consequences, if you wish, of natural selection but talking about imperatives of life is in direct contradiction with the know mechanism for Evolution, wich has no goal nor long term planing.

Second, I do no not agree that evolutionary incentives always facilitate growth and expansion in that sense. Your analogy of the petri dish is very suggestive but not correct from a Darwinian point of view. Let me give an example here:

Look at thalasemia minor for example. Is a human genetic condition that makes red blood cells becone smaller in size. In general there is no large dissadvantage here, people with thalasemia live their lifes like anybody else. There is an amazing advantage for the organism: the person with thalasemia is inmune to malaria. But there’s a dissadvantage (not for the organism in this case): if someone with thalasemia minor mates with another thalassemic then the offspring could have thalasemia major, wich is deadly since the baby will be in a constant state of anemia. So, in regions of the world were malaria is common thalassemics would in principle have your “growth imperative” since they outcompete people not inmune to malaria. But in the other hand if thalassemics become a dominant part of the population then they will mate more frequently between them and therefore their population will shrink in size since newborns will systematically die. So there you have It, an example of life being life but not expanding and growing at all. Thalassemics have an enormous ser of evolutionary incentives to be present in any large population but nevera increase in number. In principle they will nevera dissapear but their adaptation becomes problematic if the grow, so they never will be a large portion of the population.

Any situation where an evolutionary adaptation means a tradeoff between some usefull functionality and having It only for small numbers will perpetuate and never grow. There are many situations like this. What if galactic colonization is similar in that sense? What if expanding through the galaxy gives us evolutionary incentives to stop doing It inmediately? It might sound strange and counterintuitive but we have plenty of examples in Earth’s life for self-castratory expansion.

I think you are wrong. Evolution works because there must be some mechanism to achieve gene dominance, and the best way is maximal reproduction between generations. It is one of the 3 requirements for Darwinian evolution by natural selection: reproduction, variability, and inheritance.

Your thalassemia example is not proof this is wrong. The petri dish size, in this case, is the maximal population of individuals that results in the greatest spread of the allele. This seems to be a population with single alleles where chance double alleles results in death by anemia, and zero alleles result in a higher probability of death by malaria. I see no contradiction to the maximal gene population carried by individuals as suggested by Robin Datta’s imperative for life.

Sorry Alex, but I’m not able to follow your argument. I don’t really see the point, so maybe I will misinterpret what you are saying in this answer. If that’s the case please correct me. Issues I see here:

1) The three main conditions for evolution by natural selection are not “reproduction, variability, and inheritance” but reproduction (which by definition includes inheritance), variation and environmental selection (differential fitness).

2) Those 3 main conditions for natural selection doesn’t say anything about maximizing reproduction, just that reproduction must be taking place for natural selection to work. If it was just a matter of maximizing reproduction then why complex animals (which reproduce with slower rates than bacteria for example) came to be by evolutionary processes? Then how rates of reproduction dropping in specific environments can be explained (like in islands with K-selected strategies)? Just as they [this 3 tenets] doesn’t say anything about maximizing variation or environmental pressures, only that the must be there. The idea is that the 3 processes must be taking place for natural selection to work, not the teleological idea that natural selection makes life has the imperative to archive maximal reproduction or variation.

3) The way Robin Datta is suggesting his “life’s imperative” is to make the point that life must expand through the Galaxy because of natural selection. Showing why this is wrong was my point. It is precisely because natural selection takes place just with 3 ingredients that you don’t have to add this fourth. You have to prove that the growth and expansion idea emerges without exception from the 3 base ingredients of natural selection. There is no fundamental driving force pushing life to expand. Expansion is a very very common consequence of the 3 base processes but is not the only one that can happen, and when it happens in the other direction (by reducing the space of a specific allele) it is not because the 3 tenets are wrong but because different environments favor different broad behaviors of life.

I recommend reading the Medea Hypothesis book where a possible future scenario is presented where natural selection, driven by environmental pressures and incentives, takes the entire biosphere to extinction instead. This is because in the 3 ingredients there is no single instance of planning or design. Life does not act is if it has predictive power at all because it can only see the immediate relief of an environmental pressure, even if that path leads to total annihilation. Maybe that’s a solution to the Fermi “Paradox”, life simple doens’t engage in Galactic spreading because by doing so it just leaves the gene pool and becomes extinct.

Before you disagree, please have the good graces to look it up. We have been teaching these 3 necessary and sufficient factors to biology students since before I was born, and that was a looooog time ago.

The reason there are 3 components to evolution by natural selection in a nutshell is:

1. Without reproduction, there is just the organism in its baseline state. It does no t increase its numbers. So no evolution can occur.

2. Variability. Without any variability, each reproduction would be a perfect copy of the original and therefore no changes in form can occur.

3. inheritance. With many slightly different offspring, the only way to keep moving the population towards a local maxima in the “fitness landscape” is to pass on the genes to the offspring. Without this, the selection process just keeps testing the variability produced with no population change in the gene pool.

The way the genes in the population change with selection is that the serving individuals will contribute to the next generation. The more that survive the more likely the gene pool in tegh population reflects the survivors. Hence most reproduction with survival to reproduce again. sure, there are different reduction strategies, r and k, but this is unimportant as the survivors must reproduce.

Expanding into the galaxy. The history of life on Earth shows that populations will attempt to occupy any suitable niche habitat available. This can occur by any number of means, but the result is that if life can occupy an environment and continue to reproduce, it will do so.

OK, now on to the galaxy. If [litho] panspermia can occur, life will be transported to other worlds where suitable conditions exist. This is similar to the idea that terrestrial species can reach islands by natural rafts drifting on ocean currents. Once space travel is possible, then organisms like [post] humans will deliberately try to colonize new worlds. While animals and plants don’t have the same agency to colonize, humans have agency and will try to do so. Again, if we didn’t have the desire to seek new places to live we would still be living in East Africa. Instead, we have colonized every continent, including Antarctica. There are many ways for life to spread in the galaxy – by chance, by directed panspermia, by transport of human genomes either as information or as individuals in starships (slow or fast depending on technology).

What could prevent this? Just as natural barriers can prevent populations migrating to new places (e.g. mountain chains, oceans), so there might be some barriers that we are unaware of that would stop any expansion. “The Dark Forest” assumes that predatory ETI will be the barrier. For humans, technology is currently insufficient to allow colonization. Unless the great filter is still ahead of us, give it time.

The slow, long term expansion rate coupled with the slow speed of the ships (10 kms-1) seems more applicable to [directed] panspermia. Bodies ejected from their systems are intercepted by other systems, rather like our system appears to have intercepted ‘Oumuamua. Life is likely to survive the long travel times and the length of life’s survival once a planet has been ‘greened’ will be likely to be of orders of a billion years or more. The only issue is how easy it is for infected bodies to be ejected from each system to carry their life load to be captured by a suitable planet in the HZ. A von Neumann replicator whose task is to spread life after replication could operate on this scale and time, although as I have noted previously, this probably will be a lot faster than this model’s time frame.

If this is more likely than civilizational expansion, then astrobiologists should expect to see a lot of biosignatures. More importantly, the different biologies of life throughout the galaxy will be few, possibly just one from the first civilization engaged in this activity. This may even be us.

This is a very good and conservative example of the point I repeatedly have made, that even a very slowly expanding civ eventually would colonize the entire galaxy. But it would of course go quite faster if this hypothetical race had anything in common with us humans, such as the ability to fill up a planet and recreate the economy of their home world – how long would that take us? I’d would say 5000 years, and still think I am quite conservative. The same go for the colonizing vessels, even if this race for some philosophical reason only would use world ships – made from the largest asteroids, they certainly would be able to give them a better start so that their colonists would not have to spend countless generations in the bleak interstellar space.

Now that we do not see countless dyson swarms in the sky, perhaps they simply is not there – or have they developed further, to such a degree that it’s “they” who is responsible for part of the dark matter conundrum? Well if that’s the case, then this have happened exactly the same way in all those galaxies we’ve observed also. Which make it unlikely, yet one amusing idea for any writer of fiction.

I am just not comfortable with projections and models of civilizations over multi-million year time scales. Granted, we only have one data point to extrapolate from, but we have been roughly “human” for about a million years, and most of that time we have been barely distinguishable from clever animals, hardly a civilization. What assurances do we have that any race would maintain consistent long term goals and behavior for millions of years at a time? Over those time scales, even biological evolution modifies life forms substantially, it is unlikely that one species (or even its bio-enhanced or machine descendants) would maintain a coherent and consistent long-term policy of exploration and colonization.

True, over the last few thousand years we have exhibited a random-walk across the surface of our own planet, but the kind of organized and technologically supported and inspired aggressive colonization suggested by systematic exploration and colonial exploitation has quickly appeared (then just as quickly disappeared) only several times in our history. I can think of only four discrete and unconnected episodes using spaceship analogues (sailing vessels).

The Ancient Greeks colonized the Mediterranean and Black seas at the beginning of the Bronze Age. The Polynesians spread across the South Pacific during our own medieval era. During the Renaissance, Europeans crossed the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, traded with the East Indies and conquered the New World. During that same period, the Chinese (with probably the best maritime tech in the late medieval world) gave up their own colonizing and foreign trade ventures for essentially political, cultural and economic reasons. They simply decided, rightly or wrongly, that it wasn’t worth the effort. Even otherwise splendid navigators like the Vikings found that the Russian river slave trade was more profitable than colonizing North America.

We have no way of speculating the mean lifetime of a technical civilization, but even if it is extravagantly long, can we conclude that over that time they will continue building ships and exploring further and further, forever? This idea that “superior races” (civilizations, cultures, whatever) are driven by a constant urge to expand and spread just seems to me to be self-serving self-aggrandizement, not to mention just a bit creepy. We like to THINK of ourselves as bold and fearless explorers and shrewd voyaging entrepreneurs; that’s why we speculate about space travel and interstellar exploration as a hobby.

A million years from now, we may be biologically highly evolved, modified genetically or even replaced by machine surrogates and distributed artificial intelligences. But we will still be thinking like Cortez, Pizarro and Francis Drake?

Species change on million-year time scales. Sure, cockroaches, sharks and horseshoe crabs resemble their Coal Age ancestors, but they are not identical to them. An intelligent culture lasting that long would not only change its appearance and goals, it would certainly modify its expansion, exploration and colonization policy. I guess its not impossible that they would continue spreading across the galaxy indefinitely, but I, personally, don’t think its very likely. Something would put a stop to it, either natural catastrophe, a rival species, or maybe just their own common sense.

Besides, why would they bother in the first place? A shortage of resources? Not likely, a space-faring culture doesn’t need a habitable or terraformable planet, any asteroid belt around any nearby star will do fine. Over-crowding? No, population control is a lot easier than interstellar conquest. Escaping from a great natural catastrophe, like a supernova explosion? Hardly, all you have to do is move to another neighborhood. An invasion by an invincible hostile, warlike enemy bent on your destruction? That makes more sense, although starting a galactic empire seems like a counter-productive way to run and hide from a bully.

Nothing can be ruled out in this game, true. The universe is stranger than we can think. But if the velocity of light is indeed the speed limit,

then the Galactic Empire is indeed highly unlikely. Now, if you want to look for small clusters of one-race, communicating, even trading colony worlds, say in an old open cluster, then maybe you’re on the right track.

I completely agree with your post Henry. We can’t extrapolate the goals of highly advanced ET over millions of years. It simply isn’t possible. It is a mistake to compare advanced species to bacteria in a petri dish. They won’t just pursue one goal (the occupation of millions or even billions of star systems) over millions of years. Their goals would change repeatedly and possibly more and more rapidly the more advanced they get. We can’t even begin to guess what their goals might be in fact. I think we will continue to explore space, characterize exoplanets and stellar systems and eventually we may encounter another sentient species but there is very little chance we will eventually barge into a Galactic Empire ala Star Wars or that they will send their starships to steal our water or use us as feed stock or any of the other less than mature or serious SF ideas we read about.

I completely agree that there could be very few currently active high-tech civilizations in Milky Way at any given moment. But what this sim shows is that a single one who achieved true “iterative colonization” at virtually any point of time is enough. We cannot estimate the numbers to better than few oomags, but if they are not zero (or one including us), then the total number of high-tech civilizations throughout galactic history should be much bigger. My guess is in range of many thousands to few millions.

Only a small percentage of human societies went colonial, but the effect is profound – if that percentage is applied to the latter guess, hundreds or thousands of Galaxy-scale civilizations still could have existed. True iterative interstellar colonization might be rare indeed, but I’m still calling Fermi’s statement the Paradox because it’s the outliers that matter. The most expansive, the luckiest ones – much like in human history.

Romans are long gone but we still discover roman coins, pottery, etc in every part of world where they have reigned. I’m thinking about another number – a percentage of time that any given area in the world was under influence of another expansive society. In some meaning, much of Earth’s population can say we now live at such time and in such place. What this means on the Galactic scale?

These sims are giving strength to xenoarchaeology, both local and observational. Because Galaxy is old and most civilizations are probably fleeting, and also because space is transparent and it preserves artifacts much better than Earth’s surface, we’ll likely first find traces of someone long gone. There should be “Roman coins” on the Moon and “Alexandria Beacons” somewhere out there. If no one has visited Solar System during it’s lifetime, than something is truly wrong with some of FP assumptions – either with iterative interstellar colonization or with likelihood of appearance of a high-tech civilization, or both.

But intuition still says that if IIC is achievable or preferable to anyone in principle, there should be much more than defunct probes in the asteroid belts or dead Coruscants in the Core. In some sense, humans grow and expand exponentially much like bacteria on Petri dish. Here on Earth, potential of exponential growth is characteristic of all range of lifeforms from the simplest to the most complex ones, and it’s very reasonable to expect that it stays true for some areas beyond our range. But it likely ends for all of them before they go truly interstellar-faring. They turn from Wide to Deep somewhere before that.

My position regarding the failure of civilizations is that they are often enough matters that could be remedied by those affected.

The example of medieval China, for instance, may not be inexplicable, along with the several centuries weakening of other once powerful and advanced Asian countries. A British historian I only recall as Lord Kinross, in a middle eastern history — maybe of Persia — noted that these countries and the West were all linked economically, if tenuously in modern terms. In the 1500s Western countries systematically looted American civilizations and searched the hemisphere for gold and silver, especially Spain and then Portugal. Galleon after galleon of gold and silver ingots were sent home and used for commerce inside Europe. The result was a collapse in the value of Asian currencies and consequently their economies. For some centuries they couldn’t afford to adapt much Western technology or engage in pure science, not out of innate conservatism but comparative poverty. Till the late 1800s only the Ottoman Empire, occupying part of Europe, and Japan, self-isolated, somewhat kept up. The Ottomans were finally defeated in WWI, not long after Japan defeated Russia, because the Turks sided with Germany, and had already suffered a devastating loss in the 1600s when they tried to conquer all of modernizing Europe.

What I’m saying is that those countries could have taken action to keep up if they had known what was actually going on; it was a mysterious matter only because their knowledge of world events and their theories of history were inadequate.

But … Fermi paradox still here …

Question: How to get Ph.D degree in astrobiology?

Answer: Write bad (dull) SciFi story and represent is as doctorate these…

There is no Fermi Paradox.

The Fermi Paradox only makes sense if other spacefaring species are numerous in both space AND time; interstellar travel is cheap, fast and easy; and we have been waiting patiently and unsuccessfully for visitors while systematically advertising our presence over millions of years. The best circumstantial evidence we have suggests none of these is true, so the fact we haven’t been contacted or visited in the last century proves nothing.

There is no fundamental reason why cosmic civilizations can’t exist. On the contrary, the only world we’ve ever looked at closely has one!

What is debatable is just how common they are, in both space and time. The role of astrobiology is to identify search strategies with an optimized probability of success.

My personal opinion is that ETI is very rare, and we may never find another civilization sharing our galaxy. I may be mistaken, I hope I’m mistaken, but at least I do believe my position is well thought out. But I’m convinced the search is worthwhile, and we can always get lucky. The Fermi Paradox is a glib conjecture that tells us nothing we don’t already know, it is a mixture of the obvious and the unprovable and can only stifle our research and curiosity. Considering the distances and times we are dealing with in galactic and biological evolution, the fact we haven’t been unambiguously visited or contacted in the last 80 years since Enrico made his observation proves absolutely nothing. The universe is too big and too old for the Paradox to be taken seriously.

Thank you, yes. I usually express my opinion of the Fermi “Paradox” by saying the correct formulation is like so:

Assertion: Under certain assumptions, we should see evidence of ETI civilizations.

Observation: We do not see such evidence.

Conclusion: One or more of the above assumptions are incorrect.

There are huge contradictions in your two quoted phrases…

I am ready to agree with any of those arguments , but when each is used separately :-)

If you are sure that there is not paradox – but strong scientific fact – so we are alone.

If you suppose that there should be another civilization – you should accept “fermi paradox” too…

We can accept “the paradox” seriously or laugh fun from this joke, it can be refuted by real scientific observations/(ETI detection) only, but it is scientific fact which is treated as Paradox by those who are dreaming about ETI (SETI for example)…

And “no paradox” for those who does not believe in multi-civilizations in Universe…

Where’s the contradiction?

There are hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way. In the solar neighborhood, they are roughly about a parsec apart. The fact we have had no alien contact yet is meaningless. We have been capable of conceiving of, or even recognizing, an alien visitor for only a few centuries, at most. We have been making crude attempts to monitor the EM spectrum for their signals for only a few decades. We are as ignorant of each other’s distribution as the Inca and Roman empires, and for the same reason. Isolation, both temporal and spatial.

The fact we have not been contacted by Them does not mean They don’t exist. We cannot prove a negative. Whether or not alien civilizations exist has nothing to do with whether or not we

have had direct contact or communication with them after only a few decades of searching. They are totally independent questions.

Now, if we had been conducting a detailed search of the cosmos for millions or billions of years with highly sensitive equipment and active probes and found no evidence of alien civilizations, the Fermi Paradox might be more convincing, but it still would not be conclusive.

My point is that the Fermi Paradox is not evidence of anything except our brief tenure as players in the SETI game and that the speed of light is very much slower than we’d like. My personal opinion is that intelligent species are extremely rare, and that there are, at most, only a handful in the Galaxy at any one time. My evidence is purely circumstantial, but I have published it here before (search for “Reality Check”). I may eventually be proven to be mistaken, indeed, I hope I am. But either way, the Fermi Paradox will play no role, one way or the other. It is just a glib snark.

This quote is perfect illustration of the embedded contradictions in your arguments…

If you are using phrase “Fermi Paradox” when formulating your argumentations, you should decide at first it exists or not exists (as you declared on your first comment)…

Alee other your argumentations have are attempts to explain “Fermi Paradox”, that is not exist according your first comment, I am stopping here…

I know SETI enthusiasts feel very uncomfortable with reality – frequently called as “Fermi Paradox”, so call paradox (scientific fact) “The Great silence”, if it will make you feel better :-)

Given what we know, it is entirely possible we are the only intelligent species in the universe. But the fact that we have not contacted extraterrestrials is not proof of that.

Come to think of it, there is absolutely no way of proving we are alone in the Universe. However, all it takes to prove we are not is one signal or one visitor,

Its kind of like Santa Claus. There is no way of establishing without doubt he does NOT exist. However, if he should exist, all it takes is one sighting to prove it.

The “Fermi Paradox” by itself proves nothing. There could be millions of intelligent species in the cosmos, but if we have never met one it does not prove their non-existence. Why is it so difficult to grasp this?

Let me try one more time. The fact we have no evidence of the existence of extraterrestrials ins not proof they do not exist. You cannot prove a negative.

You are correct. But I would say that the estimated number of ET civilizations in the galaxy is inversely proportional to the amount of time that goes by without finding evidence of one.

Disappointing. At the very least, I would expect readers of this blog to understand the Fermi Paradox. You clearly don’t.

I have been reading about the Fermi Paradox again. I am confused by the apparent misunderstandings around the idea of such a paradox. It seems clear that the question embedded in the Paradox is valid. The Paradox just asks the question if there are intelligent species out there at some frequency over time and if they are space faring species then why haven’t we found convincing evidence that we have been visited? There are almost an infinite number of answers to the question but the question does seem valid to me. As Henry has pointed out you can’t prove the negative ie. we haven’t found any intelligent alien species so therefore there aren’t any. On the other hand we know nothing about most of the factors required for the formation of a galactic civilization. What if travel at speeds greater than c is impossible (even including warping space around the vehicle). What if civilizations have arisen, spread to nearby star systems not including ours and collapsed? What if more advanced species don’t need or want to physically explore the galaxy? What if the rate of arising of space faring civilizations which can travel at less than c is 1 per million years and all have collapsed within 100,000 years (you can make up your own numbers here) and never got a chance to visit us while actively exploring. Or maybe such species arise once every 10 million years. Or 100 million years. And what if the average sphere of exploration is 10, or 100 or 1,000 light years? We can’t even count ourselves yet as a star faring species because we haven’t sent a ship or probe(s) to any star systems yet so maybe we’ll be a measure of how hard it is. It seems to me far more likely that some unknown number of intelligent species have arisen in the galaxy, a fraction of those were or are star faring, they explored until their civilization lost either the ability or desire to do so and we haven’t been fortunate or unfortunate enough to have been provably visited over the last 10,000 years or so (call it 11 or 12 thousand years to include the entire period of organized human agriculture if you like). Does any of that make sense?

It certainly makes sense to me.

According to the version of the story I heard, Enrico (Henry, in Italian, BTW!) formulated his famous Paradox during a conversation about ETs with fell0w Oak Ridge physicists in the 1940s.

It seems a fairly reasonable assumption: if the universe is densely populated with other civilizations by now some of them should have visited us. But that conversation occurred less than a century ago. In the cosmic calendar, that is only a minute nanoblip of time. OF COURSE WE HAVEN”T BEEN VISITED YET! A century is nothing in the history of life in the galaxy. Even if there are sufficient civilizations for us to be visited (on the average) every million years or so, what are the chances we’ll get a visit in any one century interval? We may have been visited back in paleolithic times, or we may be due for another a half million years from now. The fact we have no evidence or memory of a visit means nothing. We simply haven’t been looking long enough to have chanced on a visit (or signal).

Maybe there’s a monolith on the moon, under the Antarctic ice, or continental drift has buried a probe ship via tectonic plate subduction, or maybe they felt there was no point of leaving any record of their passing for only trilobites or dinosaurs or pyramid-builders to ponder. At any rate, the idea that our generation would be lucky enough to be contemporaries of the visit is absurd.

The point I’m trying to make here is that the size and age of the galaxy, the number of stars in it, the time scales involved in biological evolution, not to mention the slow speed of light, all suggest that these alien visits are very far apart in time, and it is highly unlikely any have occurred within historical memory.

We cannot use Fermi’s reasoning to conclude the universe is empty of intelligent life. At best, it can only suggest it is rare, in both space and time. With sufficient knowledge of stellar, galactic and biological evolution it might even be possible to determine constraints on how often our planet has been “visited” in the past, or how likely it is to be visited in the future. But we don’t really know enough about those processes to quantify that thinking.

But my intuition tells me they are out there, perhaps only a handful of civilizations at any one time, but they are out there. Unfortunately, they haven’t come around to visit yet, and we’re not likely to get a visit any time soon. We probably will never find out before we die a natural death as a species.

Communication or detection seems somewhat more likely, but how much more likely I really don’t know.

The quote below from Henry’s comment:

This statement makes invalid any following speculations/explanations related to “non existing fact”.

“Fermi Paradox” can ben easily eliminated by the first ETI detection, present “no detection” state (i.e. the Great silence) can last infinite amount of time.

I am sure for our current science state it is impossible to prove that we are alone (I do not see the case how it can be proved in the future too), multiple civilizations case seams to be more scientifically valid, but it is not supported by scientific observation (facts) meanwhile.

Let’s extrapolate from the only example we know: earthlings.

The news lately covers low birth rates in the USA, Europe and East Asia, the parts of the world which could afford a colony on Mars or at L5. Global population will peak in 50 years and then begin a slow decline.

A question in 1935 was: guns or butter? In 2035 it will be: guns, space exploration or wheelchairs?

Interesting thoughts Michael. Another possibility is our population will peak earlier than that because of various environmental catastrophes ahead caused directly or indirectly by human induced climate change. We are currently pumping about 40 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. The greenhouse effect is a fact. If you increase the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere the planet can, will, and already has increased in average global temperature. Desertification is and will continue to increase. Droughts will increase in length and severity (check the data on the American Southwest for example). Storms will increase in frequency and severity (they have and they will continue to do so). Check the data from various insurance entities for records on storm damage etc. So here we are with a very clear situation. No continued global civilization unless we change. No resources or money available for large scale space exploration. Lots of guns and lots of wheelchairs for the wealthy who can survive for a while even in an unlivable climate.

Yes very interesting I wasn’t able to get the animation working but get the general idea. I also found this paper too below on a related note

Strategies for Maximizing Detection Rate in Radio SETI

https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.06594

I like this super-optimistic (and misleading) phrase: “Maximizing Detection Rate” ;-)

By default it supposes that we have some small quantity of detection, only need to improve little bit existing devices to detect more :-)

In reality detection rate is – ZERO, any multiplication of zero will give ZERO result, elementary school math…

May be authors mean multiplication of funds (money) spent for radio SETI?

Title: The Solipsist Approach to Extraterrestrial Intelligence

Authors: Sagan, C. & Newman, W. I.

Journal: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 24, P. 113, 1983

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1983QJRAS..24..113S

While I wouldn’t be so harsh as to call this paper science fiction, it does seem that the consensus here is that the scenario for colonization is contrived to fit the model of stars moving in relation to each other, and seems very flawed compared to other ideas of galactic colonization, exploration, or resource extraction.

I would be interested in hearing Jason Wright’s reply to this, justifying his colonization model.

If this helps, here is Jason Wright’s blog post on the subject:

https://sites.psu.edu/astrowright/2021/06/11/how-a-species-can-fill-the-galaxy/

I don’t understand the seemingly widespread assumption that technology will inevitably decline.

After a certain level why would it? Rather it might well continue to adapt to whatever changes are going on.

We’re talking about beings incredibly more capable and knowledgeable that us.

Maybe the record of civilizations here collapsing on falling before others makes such seem inevitable, but much of that is actually due to failed politics motivated by power lust. I’m wondering if past some point these matters will be understood and accommodated without much conflict.

Western countries, especially, are concerned with the breakdown in Western Europe of Roman power. Beyond the fall of the Republic and thus of much social flexibility (effective feedback between levels), such matters as lack of a standard method of succession resulted in almost constant civil wars. Wasn’t necessary. Hiring barbarian mercenaries taught the latter “civilized” warfare….

Stability without totalitarianism will sooner or later develop, as attempted in 1776-1787.

Technologies have become increasingly complex requiring an ever more sophisticated economy to support them. Certain technologies (artisan-based) get lost as newer technologies replace them, which means that any setback loses the underlying basis to recover unless they are rediscovered.

I recall reading a blog some years ago where the OP and commenters discussed just how much of our aircraft propulsion technology could be rebuilt. While piston engines are rebuildable (there is a thriving industry rebuilding such aircraft as DC3s and Spitfires), we cannot rebuild jet engines of the 1950s to 1960s military aircraft. They are too complex.

Think about IT hardware. When the Apollo Moon landing tapes were found, it required locating the 1960s tape players to read the tapes in order to capture the video.

One worry of archivists is that the many electronic storage formats may be lost and documents no longer recoverable in a readable form. How many of us still have floppy disk readers, cassette tape players, etc.? Recreating them from scratch may be next to impossible within the next century as information on manufacture is lost.

I was recently arguing with someone who thought that several back-to-back harvest failures would break industrial agriculture and result in civilization collapse. If that person was right how would we recreate the technologies we use? I suspect it would be like evolution – we don’t recreate the lost technologies, we just create a new path-dependent technology base instead. We may converge on similar technologies over time, or we may not.

A similar problem relates to colonization. When Heinlein was writing about colonization, his competent everyman could do many things and the technologies required to live were relatively simple. The wannabe Mars colonists of today want a lot more technological support to live but would be unable to build it on Mars even if they wanted to. Just imagine having to revert to much older technologies because nothing with imported microchips could be used. Trade with earth from Mars is quite possible but costly, but not with interstellar colonies. They are on their own. The more robust colonists might be subsistence farmers, with perhaps technologies no more sophisticated than available in the late 18th century or early 19th century. Information restricted to small libraries of paper books to ensure they can be read.

I couldn’t agree with you more.

In a techie forum like this it is not unreasonable to expect many of the participants to share an exaggerated respect for technology. But history, as you have pointed out with concrete examples, has demonstrated that fast expanding technological cultures have a poor record of leaving behind Rosetta Stones or Maya Codexes so that future generations can pick up where they left off. In my own career, I can identify many technological skills that are obsolete and destined to be soon forgotten. Sure, I can use a slide rule and a sextant, but I don’t know how to make either.

History is filled with the accounts of vanished civilizations, whose technical and scientific skills had to be recovered painfully, from scratch.

What technological enthusiasts (I hesitate to call them apologists) too easily forget is that every technology rests on a huge pyramid of interlocking technologies, industries and skills that can easily collapse if sufficiently stressed. What good does knowing how to code do you if you can’t find a computer? And what good is a computer if you can’t find a wall socket to plug it in?

When the Roman empire (or any other empire in history) for that matter) collapsed, every village still retained the knowledge of how to build houses, weave cloth, make pottery, raise livestock and grow food. They could build houses, boats, work metals, tan leather, in short, pick up where they left off. In the event of an Armageddon today, how many farmers would still know how to plow a straight furrow, even if they had an intact antique plow and harness in the barn, and livestock trained to pull it?

In the event of an earth-shattering catastrophe, I suspect only a handful of nations with a surviving village economy (like India) would be able to carry on without collapsing into total chaos. And I understand they are already over-reliant on hybrid seed, tractors, chemical fertilizers and electric irrigation pumps.

Heinlein was a fool.

This is why we shouldn’t entirely do away with basic methods of food production and the like.

I’m also guessing that some technologies like the use of simple batteries for electroplating were limited to guilds and lost when, as in the above case, Mongols systematically killed the population of medieval Baghdad.

Indeed, I can’t easily find windup clocks, which would eliminate a minor but relentless use of electricity. And typewriters, which can’t be hacked from 5000 miles away. I couldn’t build either.

I have been searching for a small corded electric alarm clock without success. That is the only way I can think of to tell how long a power failure lasts by comparing it to a battery operated clock. I can’t find one anymore. Any ideas? If there were a market for it I believe it would easily be made along with the other examples of outdated technology. But things might look different.

IIRC there was a brief fad for creating spring power for electronics mainly for poor countries with a lack of power to run such equipment. The idea spread for some items in the West like spring-powered flashlights. I suspect cheap solar power obviated the need for such technology in practice and that fad seems to have faded away.

You can still buy grandfather clocks, but they don’t have alam functions AFAIK. ;)

Try ebay.

Some department stores may have them but beware of crappy Chinese made artifacts.

I have located typewriters but no suitable windup clocks yet.

I see some people have gone back to vinyl music so there’s hope for other quite functional if (temporarily) outdated items.

Looking for low tech? Don’t use high tech search methods – well, except for a car. Wired clocks with alarms can be found at flea markets, thrift stores, antique shops and estate sales. Won’t take a month to find one. Just need to get out and look for them the old fashioned way, like learning to use a plow as mentioned previously.

While we don’t bother recreating old tech, like building previous-gen jet engines or computer systems, in case of civilization-wide technological rollback there will be much more motivation. There will be two ways – to reinvent all from scratch or try to reverse-engineer artifacts. The question here is will the latter be easier. I think yes, because even the informaton sources that are accessible at every single point are better than nothing.

Imagine we realized two centuries ago that there really was a Previous Attempt at the Eemian interglacial who have gone high-tech, and there are not just abandoned skyscrapers in the jungles (known from ancient times), but a global layer containing rusted engines, credit cards and other obscure things. Somewhere there are the libraries, few of them with intact sealed storages. Of course there will be a while before we realize they landed on Mars or what is microchip. But you can build diesel or jet engine, or even a tokamak, much faster even if all you can work with is just some printed docs with drawings and rusted artifacts that worked a thousand centuries ago. Archaeologists will know how to tease key info out of these. At all stages from the beginning to the point when we can directly read their CAD files. This is more than enough, compared to nothing. No blind search, straight to the working design.

The drawback: the easier it is in reality, the more tempting it is just to repeat old ways, mistakes included. I now wonder, what the depleted oil reservoirs would mean in this settings. Renewable energy still is something that these guys will largely have to invent themselves – they’ll know the warnings well in advance, they’ll have time, they will not have overpopulation pressure, but will they bother?

“Technologies have become increasingly complex requiring an ever more sophisticated economy to support them. Certain technologies (artisan-based) get lost as newer technologies replace them, which means that any setback loses the underlying basis to recover unless they are rediscovered.”

It’s just the opposite. The more advanced your technologies are, the more possibilities you have to replace a lost one. For example, if all our aerospace technology became lost tomorrow, we would not start redeveloping Rocketdyne’s J-2 rocket engine, we would 3D-print new engines!

I like this discussion, agree with most points here.

Can add only that present main stream to replace all analog radio and wired modes for communication and broadcasting by digital modes, make whole homo sapience communication system very unreliable in the case some catastrophe , unreliable – because it will be much more complicated (up to impossible) task to repair damaged communication systems, analog systems composed by significantly simpler parts and build blocks and requires less Hi-Tech support to function.

Just my 1 cent …

Yeah, I don’t understand either the widespread custom of setting a time-limit for ET civilizations. It seems to me just the opposite, the more advanced a civilization is, the more resilient it is to more and more types of danger.

There always will be one or another type of limit. If anyone achieved civilization immortality while remaining expansive, they indeed should be here…

There is a distinction between civilization and species. Civilizations become more and more fragile at least until our stage. Solar flares could do nothing before electricity and networks, but now they are major treat (IMO, tied first with pandemics). But the species is becoming more robust just because of population growth in numbers and distribution (in my guess, after any type of global catastrophe the bottleneck scales somewhat like square root of peak population, multiplied by severity constant). Also because of accumulation of artifacts and information. This leads to model where _species_ go extinct mostly when during one of their low-tech ages they are hit by something big, like an asteroid or major ecosystem overturn. On the timescale of geological periods, these happen often enough.

In cyclic model, instead of the longevity of high-tech civilization term there would be a product of _species_ longevity multiplied by “high-tech/low-tech ratio”.

If average lifespan of civ-capable species or families is 100 million years (order of magnitude estimation based on other universal omnivores on Earth) and the ratio is 1%, then planet-limited civilizations would spend around 10000 years in their high-tech state.

Much more complicated in colonies, of course. If any terraformation was made, local Nature will give much less refuge to colonists in case their technology fails.

“Solar flares could do nothing before electricity and networks, but now they are major treat”

No, they are a major nuisance. They couldn’t extinct us then, and can’t extinct us now.

“But the species is becoming more robust just because of population growth in numbers and distribution”

Nope, it’s becoming more robust due to technology. Indeed, world’s total fertility rate (roughly equivalent to children per woman) has been decreasing every single year since 1965 and we are now very near stagnation rate (2.44 children vs ~2.3). We still see population growth because children take 70-80 years to die.

As with much of our interest here, we can only speculate about equivalent alien species. They may be almost incomprehensibly different from us.

We’ll see, but in the meantime we must seed our reachable area.

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2021/06/beware-of-hungr.html

Beware Of Hungry Aliens The Next Time You Do SETI Research

By Keith Cowing on June 13, 2021 7:29 PM. 6 Comments

Contacting aliens could end all life on earth. Let’s stop trying, Op Ed by Mark Buchanan, Washington Post

“More alarming is the possibility that alien civilizations are remaining out of contact because they know something: that sending out signals is catastrophically risky. Our history on Earth has given us many examples of what can happen when civilizations with unequal technology meet — generally, the technologically more advanced has destroyed or enslaved the other. A cosmic version of this reality might have convinced many alien civilizations to remain silent. Exposing yourself is an invitation to be preyed upon and devoured.”

Keith’s note: Oh no. Face-eating aliens want to “devour” us. We have all seen that movie before. See what this whole UFO report release meme is stirring up? Really, Washington Post? The op ed author Mark Buchanan seems to think that just listening for indications of other civilizations will somehow alert them that they are being listened to such they will come and eat us. How? Did they file a subpoena for our radio telescope observation records? Besides, we have been sending all manner of radio transmissions out for a centry. Its too late to call the signals back.

Even if these signals from Earth are not detectable or reecognizable by another civiilzation, there are aspects of what we have done to our planet’s surface and atmosphere that they can detect. These indications are called “technosignatures” and are a subset of the overall biosignatures that instruments like the Webb Space Telescope will be searching for on worlds circling distant stars. We don’t have to send ET any text messages. They can find us much more easily across greater distances by looking at our dirty air.

Also, the author is confused as to who Breakthrough Listen is paying to do their search. They buy time on various telescopes around the world. They are not paying the SETI Institute to do all of this. And the author seems to think that SETI = SETI Institute when in fact SETI – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence – is a scientific discipline that has been undertaken over the past half century by many organizations, institutions, and individuals around the world – not just one non-profit with that acronym in its name.

The author apparently wants us to wait a while to talk to ET until (apparently) we are capable of defending ourselves against any possible invasions by hungry aliens. Remember, he said that we risk being “preyed upon and devoured”. So we need to fight back the aliens at lunch time, right? I guess that means that the author wants us to develop weaponry far more devastating than the stuff we currently have – weapons that we can barely refrain from using – on ourselves – now. Somehow that plan seems to present a more clear and present danger to humanity than listening for ET.

Yes, there should be a plan for what to do if it is time to send messages to the all of the hungry aliens. Good. Let’s have some meetings and draw up the plans. We can even do them by Zoom so as to get into the whole remote interaction thing. That should not take more than a few years. Meanwhile where is the harm in listening. Who knows – we might actually learn something from these older, more advanced civilizations about how not to blow ourselves up.

I can’t wait to see what sort of letters to the editor the Washington Post publishes in response to this op ed.

Reminds me of Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, in particular the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal. (To paraphrase) a creature so incredibly stupid that it assumes that if you can’t see it then it can’t see you, but it is extremely ravenous and dangerous. Should you run into one, the best protection is to cover your head with a towel to avoid making eye contact.

On a related note this was an interesting read

Do aliens exist? We asked five experts

https://theconversation.com/do-aliens-exist-we-asked-five-experts-161811

This is… unconvincing.

It handwaves away the twin problems of technological and political stability.

The former is enough of a challenge, and you only have to think about the problems – maintenance, repairability, transport of essential resources, and so on – to understand that it’s not trivial.

At our current level of technology we think something is doing well if it lasts decades. We have no experience of building sustainable systems in space that last centuries, and systems that can last for millennia are beyond science fiction. Not only do we not know how to build them, we can’t even imagine how to think about building them.

Something something asteroid mining really isn’t going to do the job.

But let’s assume that can be fixed. The political and social problems are still deadly. You simply *cannot* assume that a civilisation will retain a single static political identity for a billion years, with a single common goal, and an implied promise not to compete for resources with other members of the same civilisation who may arrive at the same location independently.

Especially when split into multiple independent settlements that can barely communicate with each other.

It’s simply not a defensible assumption.

You can turn it around and ask what kind of civilisation *might* be able to do that. And clearly, it’s unlikely to be recognisably human or human-like.

Machine intelligence is more likely to be politically consistent, although accumulating errors would be the equivalent of political mutations. So on this time scale all bets remain off.

We’re left with the problem that entropic decay and degradations of all kinds set a limit on these expansion models.

We do not know enough to model any of their effects on very long time scales. And simply hoping entropy is somehow not going to be a problem is not even remotely realistic.