Infrared imagery drawn from Spitzer Space Telescope data, coupled with the massive Gaia Early third Data Release (EDR3), have just given us a new insight into our galaxy’s spiral structure. The Milky Way’s Sagittarius Arm is now shown to have a ‘spur’ of star-forming gas and young stars emerging at a steep angle and stretching some 3,000 light years. The authors of the paper on this work refer to it as “unprecedented in the context of the generally adopted model of the Milky Way spiral structure.”

The spur was a tricky catch, because from our position within the galactic disk we can only see the full spiral structure in galaxies other than our own. But the authors point out that in these galaxies, spiral arms often show smaller-scale structures including ‘spurs,’ which are luminous groupings of stars, and ‘feathers,’ which are dust features. We also find branching in the main arms. Now we’ve identified a spur structure in the Milky Way.

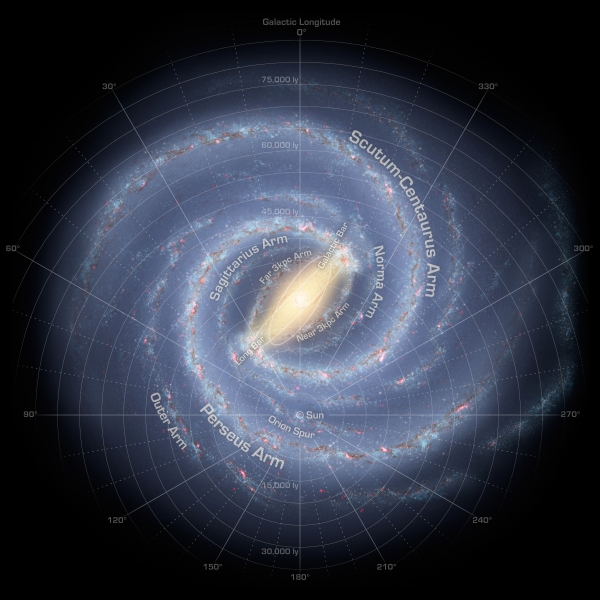

Image: Artist’s concept of the Milky Way. The galaxy’s two major arms (Scutum-Centaurus and Perseus) can be seen attached to the ends of a thick central bar, while the two minor arms (Norma and Sagittarius) are less distinct and located between the major arms. The major arms consist of the highest densities of both young and old stars; the minor arms are primarily filled with gas and pockets of star-forming activity. The new structure (not shown here) has been found to extend from the Sagittarius Arm. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Early work on galactic structure going back to the 1950s homed in on nearby star-forming regions in work that helped to define the Sagittarius Arm in the first accepted galactic map. Today we have a great deal more data to work with than earlier researchers. Michael Kuhn (Caltech) and collaborators homed in on the Sagittarius Arm, looking for data on infant stars — the paper refers to ‘young stellar objects’ (YSO) — still nestled in the molecular clouds of their birth nebulae; these are thought to align with the shape of the arms in which they are found. Indeed, in other spiral galaxies star formation follows the features of the spiral pattern.

The researchers drew on a Spitzer-derived catalog called SPICY (Spitzer/IRAC Candidate YSO) to study a nearby portion of the Sagittarius Arm, using the information to map out star-forming regions and compare their actual distribution with models of the arm. They also used a catalog derived from Spitzer data called the Galactic Legacy Infrared Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire (GLIMPSE) containing more than 100,000 newborn stars. But it took Gaia to map the result in 3-D.

The European Space Agency’s mission tracks the motions, luminosity, temperature and composition of stars down to magnitude 20. Its most recent data release, EDR3, contains astrometry information on the distances and velocities of these objects. Using EDR3, the authors inferred the parallax and proper motions for their star-forming regions and estimated their radial velocities. The team rightly points to the “renaissance in investigations of Galactic spiral structure within a few kiloparsecs of the Sun” that Gaia’s positional and radial velocity measurements have produced. The Gaia achievement is not exaggerated: Thanks to this mission, we can now examine the position and kinematics of over a billion stars.

Out of all this comes evidence for a long, thin structure of young stars moving roughly with the Sagittarius Arm and in the same direction. Kuhn points out that as the structure of a spiral galaxy becomes more open, its pitch angle increases. If a circle has a pitch angle of 0 degrees, the most recent models of the Milky Way show that the Sagittarius Arm has a pitch angle of 12 degrees. The new structure breaks radically here, with an angle of nearly 60 degrees.

Previous studies have suggested a linear structure in this region, but the high pitch angle of this spur has not previously been noted. According to the authors’ models, the structure would appear as a bright stellar feature from another galaxy, paralleling the same kind of high pitch-angle structures found in many. Gravitational instabilities may account for their formation, with mass concentrations within the arms shearing as a consequence of the galaxy’s rotation. In any case, the authors see the structure as “an excellent laboratory for examining star formation on scales large enough to be compared to extragalactic observations, but with the ability to resolve the mass function, spatial distribution, and kinematics of the individual sources.”

Robert Benjamin (University of Wisconsin-Whitewater) is principal investigator for the GLIMPSE survey:

“Ultimately, this is a reminder that there are many uncertainties about the large-scale structure of the Milky Way, and we need to look at the details if we want to understand that bigger picture. This structure is a small piece of the Milky Way, but it could tell us something significant about the Galaxy as a whole.”

Image: These four nebulae (star-forming clouds of gas and dust) are known for their breathtaking beauty: the Eagle Nebula (which contains the Pillars of Creation), the Omega Nebula, the Trifid Nebula, and the Lagoon Nebula. In the 1950s, a team of astronomers made rough distance measurements to some of the stars in these nebulae and were able to infer the existence of the Sagittarius Arm. Their work provided some of the first evidence of our galaxy’s spiral structure. In the new study, astronomers have shown that these nebulae are part of a substructure within the arm that is angled differently from the rest of the arm. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The paper is Kuhn et al., “A high pitch angle structure in the Sagittarius Arm,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 651, L10 (July 2021). Full text.

Musing about Skhadov thrusters, Dyson spheres and star lifting, a temporal perspective well beyond the current duration of the Homo sapiens species has to be invoked. Seeing star formation from its earliest stages raises the consideration of ways to modify star and planet formation that would require an extension of perspective by many orders of magnitude.

Perhaps derived species in diverse lineages unrecognizable to us may consider it “normal” to live on worlds around suns, both having been fashioned in their bygone aeons to their physical requirements and cultural preferences.

Interesting article on challenges ahead in exoplanet research and new space telescopes:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/this-report-could-make-or-break-the-next-30-years-of-u-s-astronomy/

Very interesting article.

But as has been said before, the costs of science projects are almost dwarfed by US military spending on projects to “maintain superiority”, yet that superiority is not much in evidence given the military failures since WWII. The NSF budget to cover almost all public science is a pittance by comparison. If the most expensive new telescope costs $20bn, that is perhaps $2bn/yr, chump change for military spending. We are spending our national wealth on our legions while they fail to hold Britannia and Germania. [If only Rome has directed spending towards a Greek science program instead.]

I guess the old Grand Design Spiral has a few more surprises yet…

Far from being a mere entropic relic of the Big Bang, galactic structure and evolution is revealing itself to be yet another source of emergent complexity, one operating at the largest scales and (apparently) with infinite variety and diversity. Everywhere we look, and the more we squint, the universe reveals itself in fractal detail.

Everything can be understood as merely matter and energy simply interacting in space and time. The universe appears random, chaotic and indifferent, the so-called Laws of Nature being simply an accounting mechanism to keep track of a handful of parameters. There is pattern, but no order. And yet, I still can’t shake the suspicion that even though there appears to be a reason for everything there is a purpose to nothing.

Perhaps the Great Secret of the Universe is that there is no secret.

Is a very importante moment for Galactic cartography. A few months back we also published the discovery of a new structure similar to this one; the “Cepheus Spur”. In fact this new spur is paralell to ours. This is probably not a coincidence. We might be seeing stellar formation being stimulated at the peaks of a vertical oscillation that is traversing the Galactic disc.

Our paper (including the most accurate 3D stellar map of the Milky Way currently available):

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2021MNRAS.504.2968P/abstract