Writing about Karel ?apek, as Milan ?irkovi? did in our last entry, spurs me to note that the BBC has an interesting piece out on ?apek called The 100-year-old fiction that predicted today. It’s a fine essay delivered by Dorian Lynskey on both ?apek and the Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, whose influential novel We shared a birth year of 1921 with ?apek’s R.U.R. If ?apek gave us robots, it could be said that Zamyatin gave us the modern dystopia. “If you have had any experience with science fiction,” writes Lynskey, “you will probably have imbibed some trace elements of RUR and We.”

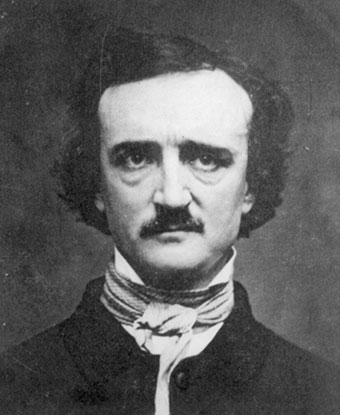

I will defer on Zamyatin, for I suspect that Dr. ?irkovi? has thoughts about him that will appear in a future essay here. However, looking toward the origins of ideas has me thinking about another literary figure, the American writer and critic Edgar Allan Poe. Always known for his tales of the macabre, Poe (1809-1848) more or less invented the detective story, but he was also influential in the origins of what would become science fiction. Beyond that, however, his thinking about cosmology was oddly prescient, and offers a 19th Century take on what would come to be called the Big Bang.

Olber’s paradox seems to have been what jogged his thinking on the matter. A German astronomer, Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers (1758-1840) took note of an observation that had long preceded him, that an eternal infinite universe should have a bright night sky. Every line of sight should carry photons from a star if stars were randomly distributed. I learned in my research for this piece that the astronomer Thomas Digges (1546-1595), who believed in an infinite cosmos, was also puzzled by the appearance of a dark night sky, as was Johannes Kepler, who pondered how to resolve the problem in 1610.

Various explanations for the dark sky would emerge, including the idea that light could run out of energy over long enough distances (this was Digges’ thought), or that the supposed ‘ether’ in interstellar space might absorb light, but it was Poe who tackled the question is an utterly novel way in a work called Eureka: A Prose Poem (1848), originally conceived and delivered as a lecture at New York’s Society Library in February of 1848. In this earnest essay he would write that some light in the universe had simply not yet had time to reach us. He acknowledges that this wasn’t a thesis that could be proven with the science of the time, but he finds the case compelling:

Were the succession of stars endless, then the background of the sky would present us an uniform luminosity, like that displayed by the Galaxy—since there could be absolutely no point, in all that background, at which would not exist a star. The only mode, therefore, in which, under such a state of affairs, we could comprehend the voids which our telescopes find in innumerable directions, would be by supposing the distance of the invisible background so immense that no ray from it has yet been able to reach us at all. That this may be so, who shall venture to deny? I maintain, simply, that we have not even the shadow of a reason for believing that it is so.

A universe infinite in age and space would be one in which light, from no matter what distance, would have had time to reach the Earth, leading to the speculation that the universe was finite in time, an idea not highly regarded in that era. Indeed, we can take the idea of an infinite universe back to the ancient Greeks, and it’s worth remembering, given the veneration in which he was held in Poe’s lifetime, that Isaac Newton supported a universe of infinite space and, in the thinking of many, infinite time, one that Olbers’ paradox seemed to challenge. In this sense, Poe is strikingly modern.

Poe’s is a universe that was not always there, and moreover, one that is growing. For even more modern, given that we are decades before Hubble’s discovery of galactic red shift, Einstein’s flirtation with and final rejection of a ‘cosmological constant,’ and Georges Lemaître’s conception of an expanding universe, is Poe’s notion of what he called a ‘primordial particle.’ It’s a bit reminiscent of Lemaître’s ‘cosmic egg,’ though of course without any data to back it up. Here is another quote from Eureka:

We now proceed to the ultimate purpose for which we are to suppose the Particle created—that is to say, the ultimate purpose so far as our considerations yet enable us to see it—the constitution of the Universe from it, the Particle.

And a bit later:

The assumption of absolute Unity in the primordial Particle includes that of infinite divisibility. Let us conceive the Particle, then, to be only not totally exhausted by diffusion into Space. From the one Particle, as a centre, let us suppose to be irradiated spherically—in all directions—to immeasurable but still to definite distances in the previously vacant space—a certain inexpressibly great yet limited number of unimaginably yet not infinitely minute atoms.

Lemaître referred to his own “hypothesis of the primeval atom,” as does Poe. In the latter, we have origin in a particle that can, by infinite divisibility, diffuse itself into space. Poe, of course, had no notion of ‘spacetime,’ as it would later be known thanks to the work of the mathematician Hermann Minkowski, who united space and time in a four-dimensional space-time in a famous 1908 paper. It was this idea of a spherically growing universe, however, that gave Poe his intuition about Olbers’ paradox.

He takes it a good bit further. Poe’s unitary particle exploded to fill the universe with diffuse matter. Gathering into clouds, this matter condensed to become stars and planets. As Poe saw it, gravity would wrestle with a principle of vitality and thought that, confusingly enough, he called electricity, which created life. But the universe’s end was clear: Gravity would pull it back together into a new primordial particle.

For a good deal more on Poe’s role in 19th Century thinking, John Tresch’s book The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021) is of obvious relevance to our theme. Tresch picks up on Poe’s cyclic cosmos, saying of Eureka:

Eureka was one of the most creative, audacious, and idiosyncratic syntheses of science and aesthetics in nineteenth-century America. Its capitalized phrase the “Universe of Stars” may suggest a parallel with the “United States.” The book’s effort to establish a balance between individuality and unity, between equality and difference — its declaration of interdependence — could be read as a restatement of his nation’s enduring tensions. But if this was an allegory of America, the road Poe saw ahead would oscillate between paradise and inferno while somehow keeping both in view — “an idea which the angels, or the devils, may entertain.”

Poe and Science Fiction

I mentioned above that Poe had also played around the edges of what would become science fiction. Indeed, in the first issue of Amazing Stories in 1926, editor Hugo Gernsback would describe the kind of tale to be presented therein as “the Jules Verne, H G Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe type of story.” This was by way of introducing what Gernsback called ‘scientifiction’ to a wide audience after earlier tales in his science and radio-themed magazines, and was taken as a kind of declaration. Gernsback pointed to Amazing Stories as “A New Sort of Magazine.”

There are various ways to date science fiction’s emergence, and I tend to favor Brian Aldiss’ view that it was Mary Shelley who started the ball rolling with her 1818 novel Frankenstein (and we can add her 1826 offering The Last Man as well), though SF origins take us into territory where argument is rife. Some critics cite Poe’s 1835 tale “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” as science fictional. But it was Poe’s “Mellonta Tauta” (1849) that SF writer and scholar James Gunn once declared the first modern science fiction story, though it’s a lightweight piece of work.

The title is Greek for something like “things of the future” and the tale describes the world of 2848 as seen through the eyes of a narrator named Pundita, who travels aboard an exotic airship. The story is chaotic and hops about between what are meant to be diary entries, casting an eye back on the era in which Poe wrote, as well as other episodes in human history. Much 19th Century knowledge has been lost, so that the narrator puzzles over things that are obvious and wields a satirical blade in examining current follies.

Here too we have a bit of astronomy, no particular surprise. In “Hans Pfaall” he had drawn heavily on John Herschel’s 1833 Treatise on Astronomy. As a boy he already had a telescope and is said to have excelled in the subject at Richmond Academy. An entry in the journal that frames “Mellonta Tauta” describes stellar motion:

Last night had a fine view of Alpha Lyræ, whose disk, through our captain’s spy-glass, subtends an angle of half a degree, looking very much as our sun does to the naked eye on a misty day. Alpha Lyræ, although so very much larger than our sun, by the by, resembles him closely as regards its spots, its atmosphere, and in many other particulars. It is only within the last century, Pundit tells me, that the binary relation existing between these two orbs began even to be suspected. The evident motion of our system in the heavens was (strange to say!) referred to an orbit about a prodigious star in the centre of the galaxy. About this star, or at all events about a centre of gravity common to all the globes of the Milky Way and supposed to be near Alcyone in the Pleiades, every one of these globes was declared to be revolving, our own performing the circuit in a period of 117,000,000 of years!

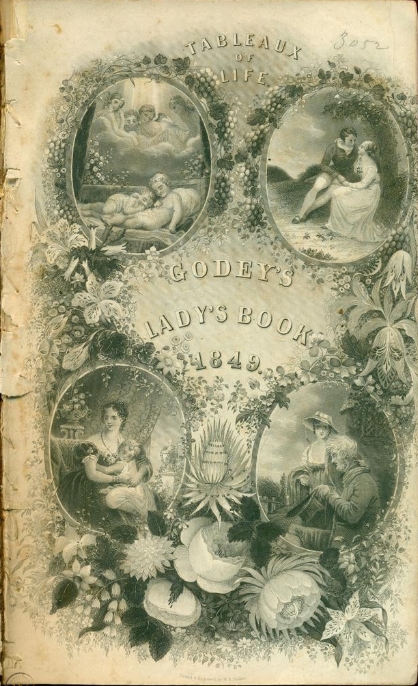

And so on. There is satire within, and perhaps a swipe at the emerging ideas of Marx and Engels, for Pundita describes a society without individualism and laces her tale with skepticism about 19th Century science even as she describes future technologies. Poe’s interest in cosmology is obviously more clearly stated in Eureka, but “Mellonta Tauta” is an interesting curiosity. First published in Godey’s Lady’s Book in February 1849, it rather fascinatingly tells of the discovery of a stone monument to George Wsahington from the 1900s and amusingly interprets it through the eyes of the future in ways science fiction writers have exploited ever since.

Image: A bound volume containing six issues of Godey’s Lady’s Book, including the February 1849 issue that featured the first printing of Poe’s “Mellonta Tauta.” Credit: Worthpoint.

So Poe has to be added into the cabinet of historical curiosities regarding the emergence of both science fiction and modern conceptions of cosmology. There is a wonderful analysis of Poe’s science fictional elements in the online Science Fiction Encyclopedia that examines quite a few Poe stories in this light. In the 101st issue of the Australian science fiction fanzine SF Commentary, edited by Bruce Gillespie, Russell Blackford makes an interesting point about where the story’s true influence may lie in an essay called “Science Fiction as a Lens into the Future”:

The story… sheds doubt on historians’ confident interpretations of the practices of other peoples living in earlier times. It is full of jokes, many of which are puzzling for today’s readers, and even when they’re explained it is often difficult to be sure exactly what ideas Poe is putting forward and which he is satirising. (Other material that Poe wrote about the same time suffers from the same problems of interpretation.) Nonetheless, Poe laid a foundation for the development of satirical science fiction set in future, greatly altered societies.

Blackford’s essay is a gem, as are many things in the long-lived SF Commentary, whose editor is, thankfully, still active and apparently inexhaustible. Issue No. 1, after all, goes back to 1969, and is also available online, along with the complete corpus in between. I wouldn’t miss an issue.

first seeing Poe’s “mellonta tauta”, my impulse was to translate “these things are gonna happen”.

Much better than my translation!

your translation is spot-on. i just wanted to give mellonta tauta some impulse.

I like the impulse. Could also have simply said: “Things to Come.” In honor of the 1936 movie about the future. I was tempted… Always good to hear from you here, Dr.!

Good point! Great minds think alike, because I made the same observation in my “Science Fiction as a Lens into the Future” essay, which you can also find here: http://metamagician3000.blogspot.com/2021/06/science-fiction-as-lens-into-future.html.

I find that his argument to solve Olber’s Paradox very interesting given that it was written when the dominant Christian Bible was claiming that the Earth (and the universe) was less than 10,000 years old. Darwin had yet to publish The Origin of Species which required real deep time. Estimates of the age of the Earth were all over the place when Poe published, with Lyell estimating 10s of millions of years and the fierce arguments between the church and the evolutionists yet to come.

For Poe to consider the issue of the time for light to reach us, he must have been aware of the vast distances to the stars, such as Bessel’s estimate of the distance to 61 Cygni and the earlier estimates of the speed of light. Interestingly, the true nature of the universe with island galaxies was not discovered until much later, so the [infinite] size of the universe might have had to be inferred. Suppose that someone had determined that all the stars were confined to our Milky Way galaxy and that the furthest stars were at the edge of the galaxy and that space was empty beyond this. This would solve Olber’s Paradox at a stroke as the extent of the distant stars was finite and relatively close.

Alex,

Even before stellar parallax was finally measured, there were indications that the stars were distant. I think it was Newton who took a metallic ball with the Sun shining on it and measured the distance from it where it appeared to have the same brightness as Sirius. Assuming the Sun and Sirius had the same intrinsic brightness, the inverse square law for light and a rough estimate for the Sun Earth distance, he worked out how far Sirius was that was only a factor of two off from it modern value.

Herschel wrote a letter to the instrument maker James Ramsden in I think the 1790’s where he says “I have seen light that has traveled for millions of years”. I have always wondered how he got that.

Herschel spent a lot of time using his observations to work out the distribution of stars in the sky and concluded that most of them were in a disk. Poe’s writing suggests he was aware of that work which was completed 40 or 50 years earlier.

I have never heard that story about Newton’s measurement of stellar distance. Interesting if true (or whoever might have done the experiment). Seems on a par with Eratosthenes’ measurement of the circumference of the Earth.

One thing in Olbers’ paradox does not consider is the inverse square law of electromagnetism applies to light. Stars are not only far apart, but light in the visible spectrum spreads out, so that anything well beyond the naked eye or 6.5 needs a telescope which explains why the sky is not bright. Try visiting a planet in a large globular cluster.

“Olbers’ paradox does not consider is the inverse square law”

It most certainly does. Even the Wikipedia article describes this quite well.

Considering it is not enough. Understanding is what is needed. Olbers’ paradox is made obsolete by the inverse square law which was new in Olbers time and not mainstream or at least not used by every scientist at that time. We also had the luminiferous ether or aether theory which was made obsolete by general relativity. One has to plug an into the first principles, and if it does not fit or is not in complete agreement with their rules, then it is wrong. If one wants to be a scientist, citizen scientist or even a citizen theorist, there are no exceptions.

“inverse square law which was new in Olbers time”

You’re digging deeper and deeper. You could not be more wrong.

The problem with Olbers paradox is a faulty assumption from the start. In an infinite universe, stars would not increase the further away one looks because there a not stars at every point in space or in every volume of space. Even in our galaxy is flat, but there are huge distances between galaxies with nothing but empty volume of space, gas molecules and dust. Consequently, the brightness of our universe would not appear to be infinite. An infinite universe must include both empty space and stars, but not just stars. The inverse square law limits our naked eye view so that any stars beyond a 6.5 magnitude need a telescope. The inverse square law also shows that we need a large telescope to see further into the universe since more light per inch falls on a larger mirror and have a larger light gathering power.

“The problem with Olbers paradox is a faulty assumption from the start.”

Good grief. That was the *purpose* of presenting the paradox: faulty assumptions about the various ideas about cosmology circulating at the time. It demonstrated *why* a homogeneous infinite universe of stars is flawed.

A homogeneous universe means the universe looks the same in every direction no matter where you are. There are more principles. The universe is also isotropic or appears the same from every angle, but one can only see that outside the milky way, but that breaks down inside the milky way which called the cosmogonic principle. https://universeadventure.org/big_bang/expand-balance.htm Olbers’ paradox is not a paradox because it is invalidated by the inverse square law which works inside our galaxy which is why stars beyond 6.5 magnitude are not visible to the naked eye based on light gathering power, so it must also work outside the galaxy and that is also isotropic: “the same laws apply throughout.” Consequently it does not matter if our universe is infinite or not since the inverse square law still applies to distant stars and galaxies.

One cannot see distant stars because there are not enough photons to stimulate the rods in your eye, the emulsion on a photographic plate, or a CCD sensor. But multiply those photons by many more stars covering the sky even at further distances and there will be enough photons to see the sky as lit up like an illuminated screen.

In the microwave, we can see the universe as fairly isotropic background radiation. If the universe was made up of stars with fairly uniform density with no end to their distance and there was no expansion causing a redshift, we would see the night sky similarly illuminated, but in the visible light.

A more earthbound thought experiment is to think of a single candle lit in the dark. Now add to that candle by distributing the candles in a uniform density until every sightline eventually ends in a candle flame. The view would be of a conflagration that was quite bright with a near-seamless view of flames, even though some candles would be quite distant.

If we view the universe as if only through the naked eye and not the telescope, then that is a subjective, Earth based view of the universe or one too much stuck in the imagination, the result of a thought experiment that does not match observations, and possibly too imaginary view.

I would like someone to calculate how far away an average star would have to be before there would be only a 50% chance for one of its photons to reach us at any given moment.

There’s nothing stopping you. But simplify your assumptions. Assume the photons are all 500 nanometres in wavelength and the Sun’s output is 3.828E+26 J/s.

No, the Paradox DOES take that into account. If the universe is infinitely large and infinitely old (and homogeneously populated with stars) then eventually everywhere you look you will see “star”. Sure, every star’s individual light undergoes inverse square dimming, but there are always more and more stars further away to make up for that. Each square degree of sky will be totally filled up with stars. In fact, you would see all of them, except, of course, those who were BEHIND the ones you were looking at. Olbers Paradox may sound naive to modern ears, but it does set valid constraints on our assumptions. For starters, it suggests that the Perfect Cosmological Principle isn’t.

H.C.,

Overall I agree. At least that was how I was introduced to the idea – and if we include interstellar dust that should compound the problem. There is one detail that discussion brings up though.

And that’s the universe age: young, old or practically eternal.

If its expanse is already infinite, then much light would not yet have arrived, giving reasons for a static universe to remain only partly illuminated. If it were very old then the light would be coming in from all over.

Several cosmologies might have been lurking in the background in these discussions. Without an explanation of how stars maintain

their shine estimates over the age of the universe could have been all over the map.

This is as good as place as any to suggest another connection:

My old anthology of Poe’s work emphasized that the American writer caught on in France first and then interest grew across the pond. Lemaitre was a Roman Catholic priest from Belgium. There are repeated stories of what parallels could be drawn between his

cosmology and Genesis and the correspondence he had with his community. But there is also the possibility that as a French speaker he was well acquainted with Poe’s stories. As we trace back origins of things we are always saying: “These things have to come from somewhere, right?…” Wonder if there is a Poe – Lemaitre connection>

Both were cosmic minded. I like the term monobloc better than cosmic egg.

Anti-atoms might be a solution to Olbers paradox. I saw a recent write-up at phys.org called “Creating a non-radiating source of electromagnetism” that could be of interest.

Olber’s paradox has been resolved for well over a century. Our universe is neither infinite in extent (space and time) nor does it exhibit a homogeneous distribution of light emitting stars. You are proposing a solution to a non-problem.

Poe’s prose poem online here:

https://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/POE/eureka.html

The Paris Review review of Eureka from 2015:

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/07/01/the-machinery-of-the-universe/

An annotated version of Eureka with its publication history and a bibliography:

https://www.eapoe.org/works/editions/eurekac.htm

Articles on Poe as a modern cosmologist:

Edgar Allan Poe: the first man to conceive a Newtonian evolving Universe…

https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.05218

https://medium.com/starts-with-a-bang/edgar-allen-poe-s-eureka-and-the-big-bang-f6c1a19e85ce

http://www.tikalon.com/blog/blog.php?article=2015/Poe_Eureka

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/edgar-allan-poe-cosmologist/

An entire book on the subject:

https://www.sunypress.edu/p-6341-edgar-allan-poe-eureka-and-scie.aspx

If you want to listen to Poe’s prose poem…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqcxrkiVwVM

Thanks for the generous citation, Paul!

Absolutely, Russell. A pleasure to have you here.