Two missions with interstellar implications have occupied us in recent days. The first, Interstellar Probe, has significance in being the first dedicated mission into the local interstellar medium. Here the science return would be immense, as we would have the opportunity to view the heliosphere from the outside. Culturally, Interstellar Probe is the kind of mission that can force resets in how we view exploration, a thought I want to expand on in the next post.

The other mission — multiple mission options, actually — involves interstellar objects like the odd 1I/’Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov, the latter clearly a comet, the former still hard to categorize. In fact, between the two, what I think we can just call Comet Borisov seems almost pedestrian, with a composition so like comets in our own system as to suggest such objects are commonplace among the stars. Whereas to explain ‘Oumuamua as a comet, we have to stretch our definitions into bizarre objects of pure hydrogen (a theory that seems to have lost traction) or consider it a shard of a Pluto-like world made of nitrogen ice. We may never know exactly what it was.

The point of Andreas Hein and team was to show not just what might be capable with an all-out effort to catch ‘Oumuamua, but more important, to offer mission options for the next interstellar wanderer that makes its way through our system. Thus the implication for future interstellar activities is that we have the opportunity to study materials from another star long before we have the capability of putting human technologies near one. These objects become nearby, fast-moving destinations that form part of the morphology of our interstellar effort.

I use the term ‘morphology’ deliberately because of its dexterity. In linguistics, the study of a language’s morphology takes us deep into its internal structure and the process of word formation. In biology, the word refers to biological form and the arrangement of size, structure and constituent parts. Here I’m using it in a philosophical sense, to argue that we continually shape cultural expectations of exploration that govern what we are willing to attempt, and that doing this is an ongoing process that will decide whether or not we choose to move beyond Sol.

Going interstellar is a decision. It comes with no guarantees of success, but we know beyond doubt that only by learning what is possible and attempting it can we ever succeed.

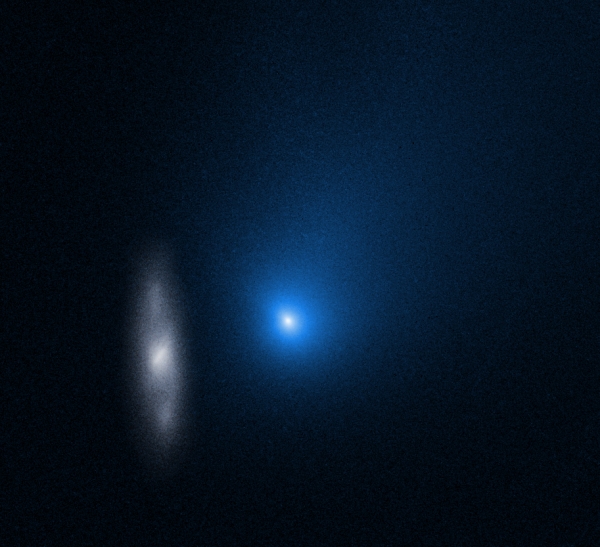

It seems a good time to revisit an image of 2I/Borisov from the Hubble Space Telescope as we ponder strategies for future missions amidst these reflections. The instrument had been observing the comet since October of 2019, following its discovery by Crimean amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov in August of that year. The Hubble work revealed among other things the surprising fact that the comet turned out to be no more than about 975 meters across. This was unexpected, as David Jewitt (UCLA) explained at the time:

“Hubble gives us the best upper limit of the size of comet Borisov’s nucleus, which is the really important part of the comet. Surprisingly, our Hubble images show that its nucleus is more than 15 times smaller than earlier investigations suggested it might be. Our Hubble images show that the radius is smaller than half a kilometer. Knowing the size is potentially useful for beginning to estimate how common such objects may be in the solar system and our galaxy. Borisov is the first known interstellar comet, and we would like to learn how many others there are.”

All fodder for crafting mission concepts. The image below was taken in November of 2019. Here we have an interstellar interloper in our own system, framed along with the distant background spiral galaxy 2MASX J10500165-0152029. Notice the smearing of the galaxy image, a result of Hubble tracking the comet, which was at the time of image acquisition about 327 million kilometers from Earth. The blue color is artificial, used to draw out detail in the comet’s coma surrounding the nucleus (Credit: NASA, ESA and D. Jewitt (UCLA).

The immensity of the cosmos taunts us with our limitations, but in considering them, we choose directions for our thinking, our aspirations and our science. This image is emblematic. Out of the darkness comes something interstellar that we now believe is just one of many such objects open to investigation, and reachable by near-term technologies. A galaxy lies behind it. How far into our own galaxy can we push as our technologies morph into new capabilities?

Exploration is a decision. How far will we choose to go?

I cannot agree more. And that image of an interstellar comet with a distant galaxy in the background sums up exactly why. Thanks for that.

I must confess some of my remarks concerning devising missions to explore deep space and to chase down interstellar visitors may seem overly critical and dismissive, it is not because I find these enterprises pointless. On the contrary, this is precisely why we go to space, and why we should go there. This is important work, both for practical reasons and to advance the human spirit.

What concerns me, and what motivates my sometimes critical comments here regarding proposals for research, has other origins altogether. In spite of our wealth and technological sophistication as a global society, I sense we may be heading for hard times, environmentally, politically, economically, and militarily. I know I am not alone in being pessimistic about humanity’s future. As the human race navigates the challenges we sense just over the horizon, all the enterprises that cannot promise an immediate payoff are in danger no matter how beneficial their long-term potential may be. We have been fishing with dynamite far too long, but those short-term benefits we’ve become addicted to may convince us to abandon research, exploration, all investment in the future.

I am convinced the answers to our problems as a species all lie in space, and that is where we must maintain a program of exploration and discovery for as long as we can. But we must also make certain our resources are invested wisely, because there are those who would prefer we divert them to more immediate, more “practical” needs. We must minimize the dead ends and blind alleys and the unnecessary expense as much as we can, and we must emphasize those projects with the higher probabilities of success.

Like I said, we’ve been fishing with dynamite far too long.

Thank you for your post Henry.

And while some sentences almost read like an apology, I would rather say that you on many times have summed up my thinking very well.

While it might be considered ‘cool’ among space enthusiasts to touch an object from another solar system with a robotic probe.

The general public will not care much, unless it’s done with a human crew, something which will not happen in the foreseeable future.

We’re indeed set for hard times, and to maintain research and exploration also when those happen will be a challenge. While deniers of the environmental problems continue to think it’s business as usual – as the oceans drown in plastic. Human stupidity already pollute space as well, SpaceX 30 000 starlink satellites will be a cascade event bomb waiting to happen. Kessler on stereoids.

https://www.space.com/spacex-starlink-satellite-collision-alerts-on-the-rise

And the Starlink satellite swarm is just one of several, all of which will compound the problem of a potential Kessler Syndrome. These small, low-coast satellites have far fewer capabilities to avoid collisions – the ISS has to move, not the satellite. At some point I have no doubt they will be seen as a pollution problem that someone else will have to clean up. Note I am not saying we shouldn’t have such swarms, but I am saying the corporation must have some proven means to deorbit them at the end of their life. The last thing we need is the example of mining companies promising restoration, then going bankrupt and leaving the problem and costs to the taxpayer after extracting the profits.

[Starlink satellites at 550 km altitude will deorbit due to atmospheric drag in a about 5 years. OTOH, OneWeb’s satellite swarm will orbit at 1200 km and pose a long term problem. Fuel to deorbit is allocated, but will that be a sufficient nethodology to cover possible eventualities?]

We stand at the edge of the proverbial great ocean. Our craft are but canoes capable of being paddled out a little way, but probably not sufficient to cross the ocean. We recall from our European history that ocean-going ships were not available until the 15th century and kickstarting the “Age of Discovery”, and we think that perhaps we should wait until such ships are available for traversing the gulfs of space.

But then we realize that the Vikings had island-hooped across teh Atlantic in much smaller sailing ships and had likely reached North America centuries earlier. But perhaps more inspiring is that the Polynesians had modified canoes with sails and navigated across the even greater Pacific Ocean by island-hopping, reaching almost to South America. Perhaps our space-going canoes are close to being sufficient to make the first “island hopping” trips to as far as the inner edge of the Oort cloud, and perhaps even farther to the nearest star. Are solar sails and aggressive gravity maneuvers all that are needed to take the plunge? Or perhaps sails pushed by concentrated energy beams, whether artificial or collected from the sun using techniques updated from over two millennia ago with the Greek legend of Archimedes setting fire to the invading Roman ships at Syracuse?

We live in an age where terrestrial distances can be traversed very quickly, although within the living memory of a few who can recall a time when some transcontinental journeys took weeks by steam ships, and airplanes were aerial canoes of sticks and paper barely able to hop a few miles. We are fortunate that we do not need to risk lives to explore and map the ocean of space, but only careers, as our proxy machine servants send back the messages of the wonders seen as they push onwards to where dragons may await.

Further….

Any thoughts on the NIAAC for an Oumuamua Interceptor and Sample Return Mission?

http://www.parabolicarc.com/2021/03/02/nasa-funds-research-into-extrasolar-object-interceptor-and-sample-return-technology/

I hope Andreas, as the one best qualified to answer this, will chime in. Otherwise, I will, but Andreas is the go-to guy on this.

“Exploration is a decision. How far will we choose to go?”

Going to Earth orbit, is needed, and largest amount money is spent doing this. The space market is over 300 billion per year and most of it is related to putting satellites in Earth. Exploration to beyond Earth orbit [or lunar surface] involves decisions by global space agencies, and less 1/10th of +300 billion per year. Of course satellites in Earth orbit can also be counted to some extent, towards the exploration of the Earth’s surface.

It seems if orbiting satellites were not related to national security and there wasn’t a global space market, then NASA and other space agencies would not or could not explore beyond Earth orbit.

So, it seems to me, having a decision regarding space exploration, is dependent on having Space be highest security issue and having global space market {which has been growing at about 4% per year}.

I tend to favor NASA exploring our Moon and then explore Mars, because I think NASA existence depends upon it.

Though in theory we could explore beyond Earth orbit, without having NASA existing.

But if NASA were to be defunded, I tend to think it would re-funded in later years- because in other theories or practical considerations, it’s needed. Or it’s seems NASA needed more many other departments and agencies in US govt. And in terms ranking in comparison to other departments and agencies as functioning, bureaucracy it typically scores quite high.

And NASA always been popular. like around 70% approval score.

If NASA explores the Moon, then we will get larger rocket and/or refueling in Space. And this means we put ever larger telescopes in orbit. And that important to explore outer solar system and the stars.

Lunar exploration if finds mineable could boost funding to all Space agencies in the World {there are all underfunded}.

And the “Exploration is a decision” would mostly to related to global space agency funding

Abraham Maslow’s hierachy of needs when applied to societies (organizations structured on hierarchical control) and communities (organizations coalescing from non-coercive horizontasl interactions) will result in perceived high-ticket low- or delayed-payoff items moved away from the base.

And while an abundance of resoures would be helpful, depletion of resources across the board complicates the issues.

A robust space program demands an even more robust human and matériel base to sustain it. While it may not seem forthcoming on earth, inching our way into space may open heretofore unseen possibilities.

Projects like Starlink will pay for an expanded human presence beyond earth. Exploration is about far more than pure science. It is unfortunate that it takes eccentric billionaires to reach beyond the narrow vision of agencies like NASA but fortunate that we have them.

Yet another professional who does not get what Avi Loeb is trying to do regarding our toddler-level grasp of extraterrestrial life and intelligence, be it unintentional or otherwise…

https://mindmatters.ai/2022/02/astrophysicist-stop-looking-for-extraterrestrial-civilizations/

In one sense it doesn’t matter if Oumuamua in particular is artificial or not. We need to look at the much larger picture and expand our mindsets when it comes to other minds in the Universe. Otherwise we are going to miss out on the biggest and most important discovery ever in our short history.