I always keep an eye on the Phase I and Phase II studies in the pipeline at the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. The goal is to support ideas in their early stages, with the 2022 awards going out to 17 different researchers to the tune of a combined $5.1 million. Of these, 12 are Phase I studies, which deliver $175,000 for a nine-month period, while the five Phase II awards go to $600,000 over two years. We looked at one of the Phase I studies, Jason Benkoski’s solar-thermal engine and shield concept, in the last post. Today we go hunting exoplanets with a starshade.

This particular iteration of the starshade concept is called Hybrid Observatory for Earth-like Exoplanets (HOEE), as proposed by John Mather (NASA GSFC). Here the idea is to leverage the resources of the huge ground-based telescopes that should define the next generation of such instruments – the Giant Magellan Telescope, the Extremely Large Telescope, etc. – by using a starshade to block the glare of the host star, thus uncovering images of exoplanets. Remember that at visible wavelengths, our Sun is 10 billion times brighter than the Earth. The telescope/starshade collaboration would produce what Mather believes will be the most powerful planet finder yet designed.

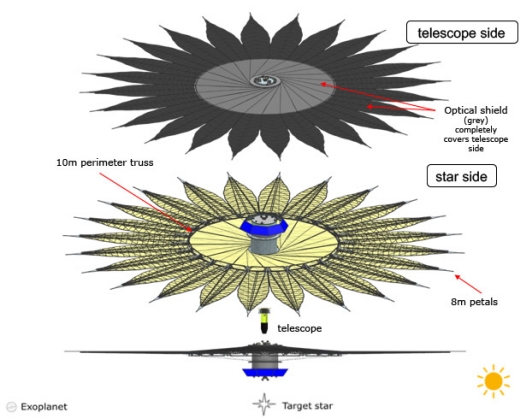

Image: Three views of a starshade. Credit: NASA / Exoplanet Exploration Program.

Removing the overwhelming light of a star can be done in more than one way, and we’ve seen that an internal coronagraph will be used, for example, with the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. It’s what NASA describes as “a system of masks, prisms, detectors and even self-flexing mirrors” that is being built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory for the mission.

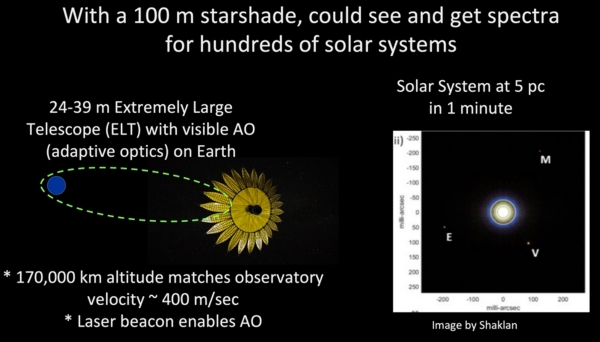

In conjunction with a space telescope, a starshade operates as a separate spacecraft, a large, flat shade positioned tens of thousands of kilometers away. Starshades have heretofore been studied in this configuration, so the innovation in Mather’s idea is to align the starshade with instruments on the ground. His team believes that we could detect oxygen and water on an Earth-class planet using a 1-hour spectrum out to a distance of 7 parsecs (roughly 23 light years. In an ASTRO2020 white paper, Mather described a system like this using a different orbit for each target star, with the orbit being a highly eccentric ellipse. Thrust is obviously a key component for adjusting the starshade’s position for operations.

From the white paper:

An orbiting starshade would enable ground-based telescopes to observe reflected light from Earth-like exoplanets around sun-like stars. With visible-band adaptive optics, angular resolution of a few milliarcseconds, and collecting areas far larger than anything currently feasible for space telescopes, this combination has the potential to open new areas of exoplanet science. An exo-Earth at 5 pc would be 50 resolution elements away from its star, making detection unambiguous, even in the presence of very bright exo-zodiacal clouds. Earth-like oxygen and water bands near 700 nm could be recognized despite terrestrial interference…

And what a positioning challenge this is in order to maximize angular resolution, sensitivity and contrast, with the starshade matching position and velocity with the telescope from an orbit with apogee greater than ~ 185,000 km, thus casting a shadow of the star, while leaving the light of its planets to reach the instrument below. In addition to the active propulsion to maintain the alignment, the concept relies on adaptive optics that will in any case be used in these ground instruments to cope with atmospheric distortion. Thus low-resolution spectroscopy becomes capable of analyzing light that is actually reflected from Earth-like planets.

Mather’s team wants to cut the 100-meter starshade mass by a factor of 10 to support about 400 kg of thin membranes making up the shade. Thus the concept of an ultra-lightweight design that would be assembled – or perhaps built entirely – in space. It’s worthwhile to remember that the starshade concept in orbit is a new entry in a field that has seen study at NASA GSFC as well as JPL’s Team X, with suitability considered for various missions including HabEx, WFIRST, JWST, New Worlds Explorer, UMBRAS and THEIA. The Mather plan is to create a larger, more maneuverable starshade, as it will indeed have to be to make possible the alignments with ground observatories contemplated in the study.

It’s an exciting prospect, but as Mather’s NIAC synopsis notes, the starshade is not one we could build today. From the synopsis:

The HOEE depends on two major innovations: a ground-space hybrid observatory, and an extremely large telescope on the ground. The tall pole requiring design and demonstration is the mechanical concept of the starshade itself. It must satisfy conflicting requirements for size and mass, shape accuracy and stability, and rigidity during or after thruster firing. Low mass is essential for observing many different target stars. If it can be assembled or constructed after launch, it need not be built to survive launch. We believe all requirements can be met, given sufficient effort. The HOEE is the most powerful exoplanet observatory yet proposed.

Image: Graphic depiction of Hybrid Observatory for Earth-like Exoplanets (HOEE). Credit: John Mather.

Centauri Dreams readers will know that Ashley Baldwin has covered starshade development extensively in these pages. His WFIRST: The Starshade Option is probably the best place to start for those who want to delve further into the matter, although the archives contain further materials. Also see my Progress on Starshade Alignment, Stability.

For more, see Peretz et al., “Exoplanet imaging performance envelopes for starshade-based missions,” Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems 7(2), 021215 (2021). Abstract. And for an overview: Arenberg et al., “Special Section on Starshades: Overview and a Dialogue,” Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems 7(2), 021201 (2021). Abstract.

I have wondered if not a star shade in space also could be used by one telescope on Earth. So thank you for showing the hybrid solution here. Since it is not economically possible to launch a large dedicated planet hunting telescope, it might be the best possible solution – for the time being.

And I link I short video done quite some years ago where they demonstrate how the starshade would unfold in space.

https://youtu.be/m7Hm7lmd338

Never heard of starshades before, this is a highly intriguing concept. Many thanks for the article!

This idea is innovative and interesting. I assume that it has a similar orbit as TESS with a apogee and perigee, so that no extra fuel is needed once it gets into it’s elliptical orbit.

Just wondering if they ever thought of using electric fields near the edges instead of complex petals, much less complicated to implement.

How do electric fields handle the refraction of light?

Highly charged surfaces affect how light interacts with the material, it may be possible to alter the pattern in a way that reduces the diffraction issue to acceptable values. In effect we make the edge of the shade into an electrified pattern that mimics the petals.

My guess because there are charged particles in space (solar wind) which would cause charged sail to move and billow.

In 2014 I was kicking around the idea of SOFIA chasing a Starshade in some sort of Earth orbit

https://yellowdragonblog.com/2014/12/18/nuclear-powered-spy-sats-in-night-time-orbits-for-permanent-eclipse-2-0/

We have a couple of good sized Earth Trojans…could those be used?

Amazing that this should be possible. I was curious what the separation would be between a star at 5 parsecs and a planet orbiting it at 1 AU, as measured at the apogee distance of the star shade. It turns out to be just under 200 metres, if I’ve done it right. So this would be the threshhold of positional accuracy required for the starshade (at 200,000 km from the Earth) if it was to block the star but let the planet’s light through to us. It sounds very impressive to position the thing so accurately!

We already have a giant starshade in orbit! It does not have a fancy sun flower design and you can only see half the planets. It might be a good test to see how well starshade would work…

Guess…

The idea of this starshade is to match the observatory’s ground velocity by revolving in an elliptical orbit. A Moon starshade or low-flying satellite wouldn’t keep pace with the ground. To be sure, the observatory is moving on a vector that varies with the Earth’s rotation, so the starshade is actually using thrust to keep aligned with it even given the orbit (plus more thrust to change orbits). The white paper claims it could stay lined up for a minute to an hour, depending on how slow the orbit is.

I do wonder if it might be easier to add up a slew of instantaneous starshade events from the Moon’s passage. The moon crosses 360 degrees in 29.5 days and a starshade needs a precision of something like 0.2 arcseconds. I got something like 0.4 seconds of observation time, but I feel like I flubbed the calculation. Still, my guess is if you can observe “enough” stars with your free starshade for tiny instants, the power of the observation should eventually outstrip what can be done with a starshade that has to move to each new star. IF you can round up the telescopes to do that and standardize them… somehow. (Laser dot on the mountainside for normalization? Also I imagine even the Moon’s low albedo by starlight might be an issue; is it?) I wonder whether anybody who actually knows astronomy thinks it’s conceivable. :)

Isn’t the Moon just occulting stars (and their systems), rather than being a starshade that blocks the light of the star, revealing the planets orbiting it?

This article from 1960 was in Scientific American, Book of Projects for The Amateur Scientist. It gives detailed information on what the characteristics of lunar occultations are and may be of use in helping you figure out the possabilites.

Useing Shadowed Starlight as a Yardstick.

“The best telescopes, such as the 200-inch reflector on Palomar

Mountain and the largest refractors, have a theoretical resolving

power considerably better than .1 second of arc. But you cannot

carry them from place to place on the earth, and furthermore their

resolving power has practical limits, imposed by poor seeing conditions, distortion of the optical train by variations of temperature and so on. Above all there is diffraction, the master image-fuzzer, which arises from the wave character of light itself. Because adjacent waves interfere with one another, the light from a distant star does not cast a knife-sharp shadow when it passes the edge of the moon. Waves of starlight grazing the moon’s edge interact, diverge and arrive at the earth’s surface as a series of dark and light bands bordering the moon’s shadow. The first band, the

most pronounced, is about 40 feet wide.

The solution hit upon by O’Keefe and his associates was a new

way to use a telescope which makes it capable of incredible resolution. They developed a portable rig (which amateurs can build) that plots lunar positions to within .005 second of arc as a matter of everyday field routine — resolution equivalent to that of an 800-inch telescope working under ideal conditions! It can also do a lot of other interesting things, such as measuring directly the

diameters of many stars. It can split into double stars images which

the big refractors show as single points of light. Some observers

believe that it could even explore the atmosphere of a star layer

by layer, as though it were dissecting a gaseous onion. Of greatest interest to the Army, the method measures earth distances of

thousands of miles with a margin of uncertainty of no more than

150 feet!

The telescope that yields these impressive results has a physical aperture of only 12 inches. The design a Cassegrain supported in a Springfield mounting follows plans laid down by the late Russell W. Porter, for many years one of the world’s leading amateur telescope makers.

The secret of the instrument’s high resolving power is in the

way it is used rather than in uniqueness of optical design. The

telescope is trained on a selected star lying in the moon’s orbit

and is guided carefully until the advancing edge of the moon

overtakes and begins to cover the star. Depending on the diameter and distance of the star, it may take up to .125 of a second

for the moon to cover (occult) it completely. During this interval

the edge of the moon becomes, in effect, part of the telescope

like a pinhole objective with an equivalent focal length of 240,000

miles. As the edge of the moon passes across the star, the intensity of the starlight diminishes, and the differences in intensity

at successive instants are measured. It is as if a 240,000-mile-long

tube were equipped at the distant end with a series of slit objectives with the moon covering one slit at a time. The resolving

power depends upon the great focal length.

The tiny successive steps in the starlight’s decay are detected

by a photomiiltiplier tube and a high-speed recorder. In principle

the measurement of terrestrial distances by lunar occultation resembles measuring by the solar eclipse technique. The moon’s

shadow races over the earth’s surface at about 1,800 feet per second. Except for differences in instrumentation and the mathematical reduction of results, the eclipse of the star is essentially the same kind of event as the eclipse of the sun. The insensitivity of the eye prevents star eclipses from making newspaper headlines, but photomiiltiplier tubes respond to such an eclipse strongly. They also detect the fuzziness caused by diffraction at the edge of the moon’s shadow. The most prominent diffraction band, as previously mentioned, is some 40 feet across — the limit to

which measurements by occultation are carried. The sharpest

drop in starlight registered on typical recordings spans .015 second

of time. Since the moon near the meridian has an average apparent speed of about .33 of a second of angular arc per second of

time, the recorded interval of .015 of a second corresponds to .005

of a second of arc. This is the instrument’s effective resolving

power.

In many respects photoelectric occultation seems almost too

good to be true. Neither poor seeing nor diffraction within the

instrument has the slightest effect on the high resolving power

of the method, and it is as precise when the moon occults a star

low in the sky as overhead.

“The whole thing no doubt, gives the impression that a rabbit

is being produced from a hat,” says O’Keefe. “It appears most

surprising that such a powerful method for detailed examination

of the sky should have gone unexplored for so long. This, of

course, we enjoy. Our group did not invent the technique: it was

suggested by K. Schwarzschild in Germany and A. E. Whitford

in the U. S. It has not been exploited before because people simply

could not believe that it works. But if I can get people to disbelieve thoroughly in something which is done before their eyes,

then I have at least entertained them — and myself.”

https://epdf.tips/queue/the-scientific-american-book-of-projects-for-the-amateur-scientist.html

A more recent version:

An improved stellar yardstick in the shadows.

Published: 15 April 2019

Measurement of the diffraction pattern of starlight during an asteroid occultation opens up new territory in stellar angular size determinations.

Published: 15 April 2019

The big question is how the The European Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) with 133 feet mirror or the Giant Magellan Telescope will see these occultations. There ability to capture the photons from bright A to nearby M type stars should be good for planet detection. There are many known stars that are occulted by the moon including many nearby red dwarfs.

Trappist 1 is Teegarden’s star are both occulted by the moon and possiably many more since the moon’s orbit is tilted 5 degrees to the ecliptic.

Aliens could have spotted Earth cross the sun from more than 1,700 star systems.

Three of these seven exoplanetary systems — Teegarden’s star, GJ 9066 and Trappist-1 — will be able to spot Earth in the coming decades and centuries. Moreover, they will be close enough to detect our radio waves. Intriguingly, the Trappist-1 system, which is about 45 light-years from Earth, is home to seven Earth-size planets, four of them in the habitable zone. Trappist-1 will enter the Earth transit zone in 1,642 years and remain there for 2,371 years.

Seven of the 2,034 stars are known hosts of exoplanets that have had or will have the chance to detect Earth just as Earth’s scientists have detected them. Three of these seven exoplanetary systems — K2-65, K2-155 and K2-240 — can currently see Earth.

One of the seven exoplanetary systems, Ross 128, could have seen Earth transit the sun for 2,158 years, starting about 3,057 years ago and ending about 900 years ago. This stellar system includes a red dwarf host star located about 11 light-years away from Earth in the Virgo constellation and is the second-closest planetary system with an Earth-size exoplanet, which is about 1.8 times the size of our planet.

https://www.space.com/finding-planets-that-see-earth-transit

Taking the .125 coverage time for star diameters Trappist 1 g could take over 1/2 second before being covered by the moon after the M dwarf was covered. This all depends on position in the orbit of the planet and it’s orbital tilt.

I am impressed! Resolving binary stars with a 12-inch telescope in 1960… and it seems like so much more could be done today! With faster time resolution, time-averaged GPS positions known for the telescopes, and a complete three-dimensional map of the entire surface of the Moon, it should be possible to place portable telescopes in carefully planned positions in preparation for an occultation event. One scope might be watching the star reemerge from behind a mountain oriented diagonal to the star’s path, while another is seeing it occulted for the first time. Different telescopes would get wider slices of information to compare. If a few satellites had some decent portable optics (and very precise resolution in time due to their orbital velocity) they could watch parts of the same star occulted at the opposite limb of the Moon. Once all the data is put together, how detailed of an image of that star can you make? Together, naturally, with any nearby planets.

If this technique works, there should be papers published with results proving the concept. Are there any? My guess is that the tiny fraction of a second that is usable isn’t long enough to even detect planets, let alone allow the collection of enough photons to characterize the spectrum of any planet. I accept that since I am not an astronomer, this is likely wrong, but I also read observation concepts that seem to require staring at a target for some time, which makes me question whether such a transient approach has any value. Conversely, if it did, why the need to carefully position the starshade rather than let it move across the sky and the tracking telescope just record the transient data as it occludes stars?

An improved stellar yardstick in the shadows.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-019-0758-3

Besides the possability of spotting exoplanets, getting stellar diameters on many known exoplanet stars would improve diameters and mass plus orbits of the planets. Asteroid shadows would cover stars outside the zodiac so a large surveys with AI could find occultations of Proxima and Keplar stars. This concept was before modern computers and AI were around so a student working on their Phd could use this for thier thesis!

While a concept involving ground-based telescopes and orbital starshade is elegant, compensation for both Earth rotation and orbital motion is going to require huge amounts of fuel. Maybe far from gravitational wells it would work better, but 100000 km starshade distance is going to make any repositioning a drag.

Considering from “scaling things up” POV, it seems to me that a nuller interferometer combined with space-based observatory, like Terrestrial Planet Finder, is a much better solution to filtering out the starlight. Here, angular resolution itself increases with separation between it’s telescopes, separating central star and planet images spatially and putting the planet out of star’s glare. Nulling adds to that. Even the effective aperture of 1 km gives ~0.1 mas resolution and brings images of a star 10 pc away and a planet 1 AU from it ~1000 diffraction limits apart. And it is much, much more easy to maneuver the TPF-like formation even in near-Earth space because it’s 4-5 oomags more compact.

Of course, the positioning requirements are much harder, mirrors have to be kept in place to sub-wavelength precision against tides and solar wind. But almost all that is needed for it is already included in the concept. Adjustment lasers could use the optical system of TPF itself, and precision ion thrusters, which are needed for repositioning, could also be used to adjust positions of free-flying optical elements.

In contrast, if the starshade at 100000 km misses it’s position, it could be difficult even to figure out the right direction for it to go. There are much less options for guidance and navigation, while even an error of several meters would let some unknown and varying amount of starlight through, drowning the planet’s light.

What a great concept, one that could bring exoplanet detection and characterisation years forward.

Re problems of membranes billowing, are there any materials/systems that could stiffen the star shade after it’s moved to a new location, to reduce diffraction errors? Some kind of piezo-electric effect, for example (total speculation I admit)?