We’ve looked before at the growing interest in exploring near-Earth space for evidence of probes from other civilizations that may have been sent in the distant past to monitor and report home on the progression of life in our Solar System. If extraterrestrial civilizations exist, the idea that one of them might have explored our system and left behind what Jim Benford calls a ‘lurker’ probe is sensible enough. We send probes to places we want to learn more about, and we would certainly have probes around the nearest stars if we had the means. Breakthrough Starshot is an example of such interest. A century from now, human probes to other stars may be commonplace.

Various places to search for lurker probes have been suggested, from Lagrange points – where objects placed there tend to stay put, with minimal need for fuel consumption – to barely studied Earth co-orbitals to the surface of the Moon. But what about Earth orbit? Surveillance of the Earth could involve probes in long-term high altitude orbits, the geosynchronous realm of our present-day communication satellites, which can always remain above the same location on the planet. As opposed to low-Earth orbits, GEO offers stable conditions over millions, perhaps billions of years.

The immediate objection is that looking into Earth’s sky is confounded by multiple factors. We have close to 5,000 satellites already in one kind of Earth orbit or another. We must also cope with centimeter-scale debris in lower orbits that seems to be increasing over time, another reason why higher orbits would be preferable for searching for something anomalous. Even so, human contamination near our planet means that using modern survey tools like Pan-STARRS is complicated and time-consuming.

If we had a time machine, we could see the sky as it was before Sputnik. But as Beatriz Villarroel and colleagues note in a new paper in Acta Astronautica, we have much easier ways of doing this. Photographic plate projects like the First Palomar Sky Survey (POSS-1) are available from earlier periods, and Villarroel (Stockholm University) is behind a new citizen science project called VASCO (Vanishing & Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations) to exploit these resources.

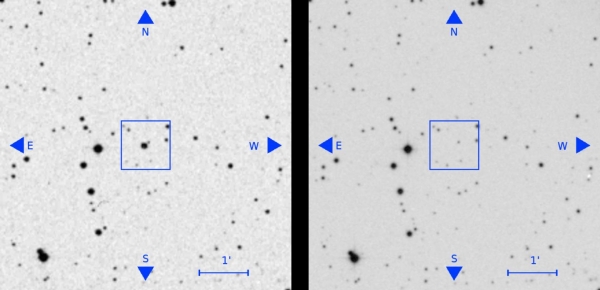

VASCO builds upon an earlier project of the same name in which Villarroel and colleagues analyzed old sky catalogs looking for stars that appear in the older plates but are not found in later imaging. In the earlier work, about 100 red transients turned up, interesting objects that likely represent flare stars worth follow-up investigation. The image below is drawn from this work (citation at the end of the article).

Image: A source visible in an old plate (left, seen as the bright source at the centre of the square) has disappeared in a later plate (right). Credit: Villarroel et al. (2019).

With the online VASCO project, the focus shifts to human volunteers, who work in the cause of finding anomalous features that may point to a technology in Earth orbit before the first Earth satellite flew. While VASCO uses the POSS-1 dataset, other plate material is available from the Lick and Sonneberg observatories and the Carte du Ciel, a decades-long mapping project from the early 20th Century. Interest in photographic plates is quickening because this is a resource ripe for analysis with our new digital tools. Thus projects like DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard), which has spent two decades thus far scanning photographic plates and archiving data.

Long-term Centauri Dreams readers will know that I champion the idea of using older datasets, which are priceless windows into the pre-digital sky. How we can exploit this material and expand our understanding with our new digital tools is an exciting area of research, and here we have the great benefit that the data have already been collected. We need build no new observatories to acquire information, but can concentrate on mining older plates for what may turn out to be new discoveries.

In the case of VASCO, the trick is to come up with the necessary filters to isolate anything that may be artificial, i.e., a technosignature. Low Earth orbits remain relatively uninteresting because they do not fit the long-term survival we’re presuming in a lurker, although fast-moving point sources in a long exposure can readily show natural objects like asteroids or meteors. An object in geosynchronous orbit may throw a glint when observer and reflective surface happen to be precisely aligned. But single glints are not enough. The authors are after indicators that cannot be confused with natural phenomena and are not the result of instrumental or photographic defects.

Image: This is Figure 2 from the paper. Caption: Fig. 2. A typical streak. The POSS-I streak found in a red image identified through the citizen science project shows the effect of tumbling and is a possible near-Earth asteroid but is also a possible candidate. The streak is roughly 40 arcminutes in length and unlikely to be a meteor with its angular velocity and pattern of first being dim, then brightens, and then dims once again. The typical exposure time for POSS-I images is about 50 minutes. Credit: Villarroel et al.

While a reflective satellite can produce a short, powerful glint, the glint shows a Point Source Function (PSF) shape that does not help us much. A point source is one that is smaller than maximum resolution of the equipment. An image of it seems to spread, a factor we must consider because of the diffraction of the telescope aperture. From the paper:

Satellites that are uniformly illuminated at low- or medium altitude orbits leave clear streaks in the long time exposures from old photographic plates as they move at speeds projected as hundreds of arcseconds per second. At higher or GEO altitudes the presence of satellites or space debris can be detected by fast, transient glints caused by surface reflection of the Sun. When the reflective surface of the satellite coincides perfectly with the position of the observer and the Sun, a short but powerful glint can be observed. Despite the fast movement of the satellite, the very brief reflective alignment means that the resulting short duration glint has a Point Source Function (PSF)-like shape…

And it turns out that a single glint on older photographic plates is indistinguishable from an astrophysical transient. In fact, ground-based searches for such transients today often pull up solar reflections from artificial objects in geosynchronous orbits. Moreover, 75 percent of glints from GEO, while not associated with any known object, are almost certainly centimeter-sized human space debris.

Going beyond the single glint, then, the paper analyzes multiple glints, and notes in particular glints with point source functions that occur along a straight line – which can occur when a spinning object reflects sunlight – and triple glints, another sign of possible rotation. And indeed, multiple glints have been found in at least one image exposed in 1950, though it is impossible to rule out contamination or emulsion defects on old photographic plates. What the authors are after is something more reliable:

The smoking-gun observation that settles the question unequivocally, is the one of repeating glints with clear PSFs along a straight line in a long-exposure image. When an object spins fast around itself and when its reflective surface faces the Earth, some of its parts could reflect sunlight. That results in multiple glints following a trail in an image. The number of glints might depend on the geometry and the speed of the rotation of the object. An object with only one single reflective surface that spins slowly will produce fewer glints than an object with several reflective surfaces that, moreover, spins fast. From the period one can also determine the shape of the glinting object.

This, then, is the kind of signature Villarroel and colleagues hope to find during the course of the VASCO investigations:

An exciting aspect of these suggestions is that precisely these type of objects could be found during the course of the VASCO project [8], [29]. Among the many objects classified as “Vanished”, we could discover both single and multiple glint objects. Also through automatised methods, we seek to identify all cases of multiple glints within a small area of 10 × 10 arcmin2, and to see if any of these represent cases where the glints follow a straight line.

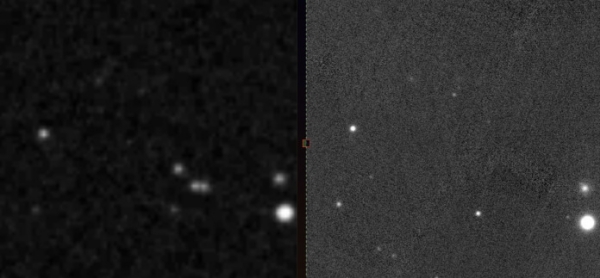

Image: This is Figure 5 from the paper. Caption: Fig. 5. Triple glints. An example of a triplet glints in a red POSS-I image from 1950s. The left column shows the POSS-I image, and the right column the Pan-STARRS image ( year 2015). The example is from Villarroel et al. (2021) [54] and uses the VASCO citizen science web interface. Credit: Villarroel et al.

A series of multiple glints along a line in photographic plate images, if found in the VASCO plates, would be of great interest, but there is a ticking clock, because trying to locate any such object today comes up against the growing volume of human-made space debris. The authors argue that searches for technosignatures in photographic plates should thus be done as soon as possible, and preferably performed on datasets beyond the POSS-1 material now used by VASCO.

A sky without human contamination in orbit is available through these plates, and if an object in geosynchronous orbit has been left behind – perhaps millions of years ago – as an observing platform or other kind of probe, this method is one way citizen science can be employed to spot it. Just how long a reflective surface can endure in an environment of dust grain and micrometeorite collisions is debatable, but of course we know nothing about what measures probe builders might take to protect their equipment. The authors think the imponderables keep VASCO a viable project.

The paper is Villarroel et al., “A glint in the eye: Photographic plate archive searches for non-terrestrial artefacts,” Acta Astronautica Vol. 194 (May 2022), 106-113 (full text). For earlier work, see Villarroel et al., “The Vanishing and Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations Project. I. USNO Objects Missing in Modern Sky Surveys and Follow-up Observations of a “Missing Star,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 159, No. 1 (2020) 8 (full text). Thanks to my friend Antonio Tavani for the pointer to the 2022 paper.

I fear that a true lurker probe would incorporate a non-reflective surface. However this is a very worthwhile study and I wish the VASCO project every success.

Reading through the 2 papers indicates that multiple “glints” are not rare and that 4 may be needed to start being really interested.

The assumption that there are no satellites in the sky pre-1957 is correct, but there are other possible objects that might “glint” in the field of view of a telescope taking a long exposure image of the night sky. This could include birds or insects, and not let us forget human artifacts like airships, aircraft, and weather balloons. Such prosaic causes need to be ruled out – a difficult feat for transients only captured as fuzzy light spots on a photographic plate.

Not to put too fine a point on it, these “glints” are no different from the supposed alien craft buzzing the skies. Multiple instances of a “moving” object (the telescope is moving to track the sky) that may, or may not be truly moving and may, or may not be in orbit.

Pre-1957 plates should perhaps be used to detect stars and other celestial objects that are transients or have displayed large relative motions in the sky. Hoping for alien Lurkers seems a stretch. The author suggests that such Lurkers may have been hit by meteoroids flaking off reflective parts. If the Lurker is meant to be a hidden surveillance probe, why not make it fully camouflaged (black) and resistant to damage that would expose reflective components, like shiny metal plates? As these possible probes are captured pre-1957 and are no longer detectable, there seems little reason to send a probe in their direction to see if anything is there. Contemporary glints could be anything from known satellites to debris, again suggesting little point in close inspection, unless in the future we are doing extensive orbital debris cleanups and waste disposal, and might serendipitously come upon a damaged alien probe (c.f. Brin’s novel “Existence”).

Paradoxically, now is the time for ETI to orbit a surveillance probe. Who will look for one “glinting” amidst all the satellites and debris in orbits from LEO to GEO, and beyond? I think Benford is right that looking for Lurkers in other locations, such as Earth co-orbitals or even on the Moon makes more sense; to reduce the huge numbers of likely false positives.

Actually, although GEO offers stable conditions over ~centuries, on longer timescales, calculations show that they migrate to a few areas in the 360 degrees of the GEO orbit. This occurs because of the not-entirely-spherical nature of the Earth’s gravity field. So that’s where to look for any longterm Lurkers.

Dr Benford-

I am an amateur astronomer living in S Florida. On both 31 Dec 1999 and 1 Jan 2000, about midnight EST, I observed about a half-dozen strobe-like flashes (each night) just south of the Celestial Equator in the constellation Orion.

These flashes (about magnitude -1 or -2) were spread out over a period of about a half hour each night They looked exactly like the strobes carried by high-flying aircraft, except these lights did not move amongst the stars, they appeared to come from the same spot on the celestial sphere as best I could determine. It is difficult to visually fix the position of a flashing light that does not repeat rapidly.

I don’t think these were Lurkers, I suspect they were reflections from GEO orbiting satellites either being ranged or calibrated by some ground based laser. Alternatively, I also may have witnessed a deliberate attack on a spy satellite, perhaps one of the last battles of the Cold War! I do not believe these were solar reflections. According to my calculations, these flashes occurred in the Earth’s shadow.

A few days later I read in the press that some of our ‘orbital intelligence assets’ had experienced some “Y2K” issues, but they had ‘not been permanently affected’.

I’ve always suspected there were some stable “sweet spots” in the Earth gravity field where high-priority geostationary spacecraft (like surveillance satellites) might be parked. It appears you have given this issue some thought. Would you care to speculate on my observation?

We have been LASER ranging to the first of the LAGEOS satellites since 1976 (my first contribution being July 1979). These satellites are in 5,900 km orbits and have expected lifetimes of 8.2 MY. A Lurker close to the Earth with a lifespan of many million of years must be considered. What is particularly interesting though is that as such a spacecraft would be quite accessible to advanced target lifeforms, us in this case, once discovered, what then? (The lack of a high pitched squeal once touched would be quite disappointing ?)

Hi, Dave

Please read my response to James Benford, above, concerning laser ranging to earth satellites. I feel you may have much to add to that discussion.

When I was ranging to satellites, LAGEOS was our principal target. These were early days and satellites equipped with the necessary corner cube reflectors were few. You would not have seen a reflection from LAGEOS unless co-located with the LASER and likely not even then due to a very low received visible signal strength. Today, systems range to over 200 satellites with the beam striking odd surfaces. However, I doubt that a reflection would be visible. This is the case for peaceful ranging systems, for high-energy military applications, the results might be quite different. I have no privileged knowledge though.

Seems there was quite a few objects flying around the earth moon system before satellites where launched. From the journal Icarus;

Bagby’s phantom moonlets.

Jean Meeus

https://ur.booksc.me/dl/2134824/a3f687

1913 Great Meteor Procession.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1913_Great_Meteor_Procession

Which I would say is one of the most unusual encounters and seen over such a large area by many people.

These objects are of micro robot alien spacecraft that enter the earths atmosphere!

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FVTKp4cWQAA3P6J?format=jpg&name=large

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FVTKp4bWYAQjjj5?format=jpg&name=900×900

Micrometeorites as small .3 millimeters then rain down on your roof everyday! Could be an easy way to get micro AI robots here without anyone noticing. ;-}

Scottmp123 @Scottmp123

Jun 15

Here’s a side and top view of an extremely fresh from outer space micrometeorite. From the side view you can see some iridescence on the bottom left and on the top right the glass is so fresh it’s appears almost see-through under the microscope.

https://twitter.com/Scottmp123/status/1537076197695315969?s=20&t=_v0k-ekremoTKLHuZQkVLg

Project Stardust

https://www.facebook.com/micrometeorites

https://projectstardust.xyz/

The de facto aerobrake that the Great Daylight Fireball did in 1972 while holding together for the whole of the Super-8 footage impressed me. That should be the place to start.

A daylight fireball flew over the U.S. and Canada on Aug 10, 1972 with its trajectory tangential to the Earth surface and perigee at ~ 58 km. The fireball body lost only a part of its mass and continued to move in a changed orbit. Unique observations by infrared radiometer tracking were acquired by Rawcliffe et al.

Yes, that would also be a great way to disperse biological and viruses or AI micro robots over a large area and fly to the next planet and do it again. I’m just wondering how many of these micrometeorites in my gutter might be from outside the solar system? This would be a great project for schools and universities to find and analyze plus they have plenty of roof area to get samples from! Just think of all that deep space debris sitting just a few feet above our heads…

The trajectory is very striking. Could it have been a probe sampling the atmosphere? Has anyone calculated where it’s current position would be?

What would it take to find and fly to its assumed location?

I wonder if it came from the same general location as Ouamuamua…maybe that as a spent stage?

I would also like to track the strangelets talked about here…maybe recover them:

https://www.wired.com/2003/02/matter/amp

This is super interesting!! Centauri Dreams is a godsend as most of your articles make me think about SETI and related topics in new ways, and this is no exception. I have already heard “Lurker Probes” discussed in UFOlogy circles as a possible explanation for some UFOs but I had no idea that the concept has been discussed this seriously in mainstream science let alone to the point people had actively started searching for them…

Glad you’ve found it interesting, Simon. SETA — the Search for Extraterrestrial Artifacts — is getting a bit more attention since the days when Robert Freitas ran the first SETA search I’m aware of, looking at the Lagrangian points. I think we’ll be reading more about it given the high quality mapping data we have available for the Moon and the new interest in the Earth co-orbitals.

Hi Paul

Duncan Lunan’s Boötis Probe translations from 1972/3 inspired astronomer and BIS member Anthony Lawton to look at the Lagrange Points for lurkers in c.1973. Almost coincidentally Lunan has published a two part up-date here:

EPSILON BOÖTIS REVISITED

And here…

Epsilon Boötis Revisited, Part 2

…most of which is from an “Analog” essay in 1996, plus updates in the 26 years since.

The recent confirmation of the Kordylewski Clouds may or may not be relevant, since they could be remnants from an artificial enhancement as Lunan hints.

A worthwhile question for anyone who knows Phil K Dick’s 1970’s obsessions, is whether Lunan’s ideas directly influenced Dick’s VALIS experiences, which began in 1974. The timing is suspicious.

Interesting! I didn’t know about Lawton. Thanks, Adam. Interesting, too, re the timing of Dick’s experiences. I assume he would have been aware of Lunan, since he would have followed Analog in those days (which is where I, at least, first encountered Lunan).

Dear Simon

It may have not been your intention to do so, but your post implies the “mainstream science” community is hidebound, hopelessly orthodox, pathologically conservative, and otherwise incapable of thinking ‘outside the box’.

I think professional scientists are perfectly capable of wide-eyed speculation, in fact, its a vital part of their job! They are just keenly aware of when they are doing so, of its value, and its limitations.

After reading it seems to me that geostationary orbit is a very attractive techosignature search location. But for a space-based survey probe.

This thing, equipped with ion engines and a modest-sized-telescope, could do many things at once. Inspecting old satellites and examining them for space damage. Doubling as space-based observatory, another mid-sized telescope in space capable of watching transits and many things else. And of course inspecting unidentified objects up close, finding dead lurkers among them. (and springing and chasing living ones :D )

The orbit stability is megayear-scale there, and a probe on the right orbit could swipe the whole 5000 km-wide torus with geostationary centroid in few years, spending some fuel only to get a closer look occasionally. Or no fuel at all, if it has a sail or tether of some kind.

Just what can we infer about the visibility of Lurker probes? There are only two options.

1) They will be as deliberately conspicuous as the advanced technology of their makers can make them. They’ll have flashing lights, radio beacons, AI com lasers, thermal IR generators and highly polished reflective panels. Their creators will want them to be spotted in case there is any intelligence where they are headed.

OR

2) Their builders will be cautious and paranoid and will make every effort to cloak them in the most advanced stealth tech they have available. In fact, they will probably incorporate self-destruct devices, or escape maneuvering protocols to cover their tracks after they complete their mission and report home. They will not be designed to be found.

These are the only two options. There are good reasons for both of these strategies but absolutely no reason to ignore the entire issue and make no effort to do either. In other words, they will be designed to be either easy to find, or impossible to spot. Nothing in between.

It’s certainly possible that the technology or mission they were programmed with may be lost or damaged, which means locating them

will be just like finding any other derelict or floating debris, but that won’t be they way they were designed, and its not likely that we should plan for that.

Regarding the #2 option. The ability to detect an otherwise invisible lurker hiding in the open, no matter how well it wants to hide itself, is likely within human grasp shortly. In 3500 BCE we discovered writing, and in the 5500 years time since, we’re in space ourselves. We’re quick learners. We can seriously discuss alien lurkers and strategies and imagine how one may camouflage. Give us a few more years (a century or two?), and we’ll be able to find them — if they’re there — regardless. So unless lurker camouflage is indistinguishable from magic short of gods level status, it’s going to be found. My point is, the lurker creator would know their own limitations as well.

I’d think that a lurker probe would be utilitarian, much like our own probes are, packing what needs to be packed and no more.

That’s because I don’t understand the point of escape protocols. Once the lurker is detected and knows it (maybe we paint it with some form of particles based RADAR-like thing, who knows), it’s going to be seen escaping. If non-detection is the goal, then the mission failed, and escaping nor self destruction can fix that.

I missed something. What?

Thanks.

dear random engineer

Re Option 2, a stealth probe would not have to be undetectable, it would just have to look like any other natural object that might be orbiting a star’s asteroid belt, Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt. That is certainly easier to achieve than complete invisibility. A lump of ice, a cold piece of slag? Its anonymity may not be guaranteed, but it would certainly be likely, regardless of its makers’ technological sophistication, or ours.

As for escape maneuvers or self-destruction, you are correct in pointing out that its departure or demolition would be more likely to give away its presence, or even its nature. But it is also possible the probe was designed to visit multiple targets, and after completing its survey it would move on to its next destination, in as stealthily a fashion as necessary–or possible. If the visitor is on an extended mission visiting many potential targets, it probably does not expect to hit paydirt on all of them. It may also be prepared to encounter locals who do not want to be studied, or who are hiding themselves. In that case, the best strategy may be to just leave as quickly and quietly as possible, regardless of the trail left behind. The possibilities are endless. So are the options.

The Devil’s Advocate can always conceive of a scenario where all precautions fail, but the Probe Makers would know that, and try to devise their machine so it had as high a probability of success (however they choose to define it) as possible. The only way a scout can guarantee to be totally undetectable is to not go at all.

Stanley Kubrick was ‘insanely’ brilliant. I believe he got it right in ‘2001 A Space Odyssey’. Once a creature that was possibly on a path to intelligence (and given a helping hand by the first manifestation of the monolith) attained the capability of detecting and recovering an artefact buried on the Moon, the monolith’s creators would be very interested to know. No need for either ‘bells and whistles’ or stealth – the creators would regardless remain quite unfathomable. As a possible extension to this thinking, had the monolith contained entangled particles over the time that the Lurker had taken to reach the Earth, possibly millennia and these were part of a system triggered once the monolith was touched, as in each instance in the movie, its creators would have known of our capability instantly. This if one believes in the violation of Bell’s inequality being possible. Kubrick’s monolith is astoundingly brilliant. (I say Kubrick’s because in Clarke’s vision it was much less so.)

I agree with Alex Tolley. We’ve already concluded that such small objects like lurkers would be difficult to find due to their small size, especially if there were designed to spy. They have to spend some time in observation, so it pays to use stealth and even a coating which can’t be seen even in the infra red and the visible spectrum like black carbon or charcoal making them low observables. A geostationary orbit is too far away to be seen from Earth with a telescope at least close up. We could never get rid of the ambiguity unless the lurker reflected visible light and it was made out of some kind of reflective metal which could be seen with a spectrometer. I don’t think it would hurt to try and look.

The idea that these would have to use a Geostationary orbit is hopelessly obsolete or trapped in our knowledge of the past because as I wrote before, if a ET civilization was much more advanced than us since they have interstellar travel, they would not want us stealing their technology and getting a faster advancement than we would on our own. Consequently, it is logical to assume if their probes were not mobile like geostationary probes, then they would not leave them behind for us to find them. The recent observations of UAP’s by our military could be used to support such a hypothesis. For that reason, lurkers and Von Neumann probes are probably old science fiction.

H Cordova: “Re Option 2, a stealth probe would not have to be undetectable, it would just have to look like any other natural object that might be orbiting a star’s asteroid belt, Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt.”

Why would a lurker need to cosplay as a rock? It was only 65 years back that man started slinging coffee can sized satellites in orbit, and you could have parked an obvious school bus or eiffel tower in the asteroid belt and it woudn’t have been detectable as artificial. We didn’t have the ability to image. (Do we even now have every asteroid etc imaged?) I don’t know that we have much more actual imaging of kuiper belt objects. So fast forward to 2122 and I’m pretty sure that by then man can detect a disguised asteroid. The lurker observation window would be artificially small, say 150-300 years? In the sweep of time that’s not much. An eyeblink. A disguise doesn’t seem to buy anything.

Speculating on the capabilities of alien tech is probably as pointless as forecasting our own future capabilities. But physics is physics. Tiny satellites may be hard to detect, but they also have little room to carry much stealth gear. And any active device, regardless of size or technological sophistication, will generate waste heat which will be easily detectable.

However, an object simulating a comet or planetoid (or anchored and dispersed on the surface of a small world) would be massive enough to be packed with cloaking devices and the means to dissipate waste heat in an anti-sunward direction. No strategy is guaranteed to work all the time, every time, but it is always possible to improve your chances of success.

If you haven’t mastered the art of invisibility, you can always hide in plain sight.

I am not sure geo orbits are quite as stable as you say, especially over thousands and millions of years. It is true they don’t face much threat from re-entry, but the satellites themselves will be perturbed by the Sun and Moon and sooner or later no longer be in the geosynchronous orbit. It might make more sense to look at MEO orbits, or even supersynchronous orbits rather than focus on geo.

“over thousands and millions of years”

Which leads me to one of my arguments against any ancient orbital or deep-space lurkers; the ability to perform station-keeping and attitude control over extremely long timeframes (or at least the ability to preserve the *capacity* to perform said functions). Best to sit on a planetary surface like the Moon, I’d think.

I believe that Clyde Tombaugh performed a search in the early 50’s for natural Earth satellites. I imagine it would be interesting to examine any of those photographic plates.

Lurker stealth technology could be any of the types we know, and some we don’t.

Hiding as a natural object, light-absorbing black (we have a near-total non-reflecting paint now), radar-limiting profile (like stealth aircraft), light bending with meta-material camouflage (at some point will it be as good as the thermoptic camouflage in the animé “Ghost in the Shell”?).

A probe with just a low radar profile and painted black would be next to impossible to locate unless it was actively transmitting in the em spectrum. If the surface profile was symmetric, there would be no glints, just a very high magnitude point source that might at best look like a meteoroid on an old long-exposure photographic plate, and therefore unrecognizable as a multiple-glinting object in the image. Without prior knowledge of its location, we wouldn’t even be able to target it with lasers to try to paint it and get some sort of reflection. Off the top of my head, the only obvious, albeit somewhat damaging way to locate such an object would be to spray a lot of chaff-like material into space and see if any hidden object exposes itself by altering the trajectory of any of the pieces. The cost of adding all this debris in space would be awful unless there was some way they could be guaranteed to blow away in the solar wind after a short time. [Even paint flecks can damage objects in space so this could be very damaging to our many satellites, just in order to see if anything is in orbit that shouldn’t be and isn’t our own debris. ;( ]

Interesting idea! That sounds like a Sun-sized job. But the Sun does it! We have had probes listen for electromagnetic “sound” before – could one of them “hear” with such exquisite sensitivity that the rebounding ions of solar wind from a small object make a noticeable noise as they cross paths with undeflected ions?

Alright, yes… the aliens doubtless have a way to deal with that too. :) But at least someone might hope to spot all the Lurkers with more human origins and perhaps go on to study how much nuclear material is on board.

I was thinking the same thing myself, Alex Tolley. The idea of lurkers and Von Neuman probes might not be obsolete since they would be very difficult to detect. They could have stealth technology, and carbon or charcoal covered coatings which would make them dark against the blackness of space rendering them invisible to the visible spectrum, and they could have infra red light absorption coating, so they would not even show up in infra red. With a sophisticated radar, they could leave the area when they see any of our search spacecraft and be long gone before we could detect them. Also they could have a self destruct or have solar power, so they could leave orbit and fly into our Sun when their mission was complete without leaving any trace. This would make them very difficult to find. The only way to foil them would be to have a lidar connected laser beam to a satellite in space and when they past through the beam and blocked it, we would know something was there. Another way would be to have a telescope with a laser spotlight mounted on top it that could change frequency or go from infra red to ultra violet and we could see the reflection off of it if it was at the right wavelength.

It is said that some spysats in geosynchronous orbit utilize large non-reflective balloons to block themselves from view on Earth. If we can do that…

A comet like trajectory where the probe “wakes up” every Sunward pass of Earth-snaps a few pics-then goes back in frozen hibernation-is also possible. These Heliconia Probes thus allow time-lapse studies, long life, and limited opportunities for interception. Now-bearing this in mind-where might the daylight fireball have been during the Carrington Event? Most of a Comet like orbit keeps you safe-but Carrington had teeth. Moreover-a ‘failed Carrington event set off mines at sea during Vietnam around 72’ as I recall. That could fry an inbound probe!

Hello everyone,

i have been participating in VASCO’s Citizens Science Project since January 2022. It’s a great way to help investigate missing objects with simple tools, and it’s also very exciting.

My best hit was ID#33093. Check it out at http://34.88.90.37/#/.

You will see that three objects (right side) have disappeared in the new photo.

Best regards

Josef Garcia

Some scientists are not just looking for ETI, they are searching for other entire universes. Read on…

https://www.ornl.gov/news/physicists-confront-neutron-lifetime-puzzle

The sheer fact that such a bunch of skillful, highly educated, intelligence infused scientists unanimously agree that looking for “aliens” using century-old shots of the sky is a great idea, well it makes me doubt of the soundness of our vision of the world. . We are not even able to determine the nature of the “people of the clouds”, which are immensely closer to us. I guess that only when will we be able to finally forget all of the episodes of the infamous “star trek” franchise some seminal advancement in the field will occur.

I don’t know. By all means, look for lurkers in all kinds of places, we never k ow what else we may find.

But to me here is a screaming paradox much much worse than the Fermi paradox.

If there was a technological civilization advamced enough to not only send a probe our way, but to also put it in orbit around our Sun which is some orders of magnitude more difficult than just letting a probe scream through iur system. And, since there is absolutely nothing special about our Solar system compared to the millions of other stars in these parts, one can also assume that they would have sent lurkers to most of those millions of stars as well, requiring incredibly huge amounts of resources and energy.

Then that would, to my mind, make them an extremely noisy civilization, harnessing a significant portion of their star’s power output. And they would be in our backyard, too.

So, where are they?

I can’t for the life of me see how such a noisy bunch could just go quiet.

They would also almost certainly be multi-planetary, so not so easy to be wiped out by any old catastrophy, either.

We’ll be Building Self-Replicating Probes to Explore the Milky Way Sooner Than you Think. Why Haven’t ETIs?

JULY 19, 2022

BY EVAN GOUGH

The future can arrive in sudden bursts. What seems a long way off can suddenly jump into view, especially when technology is involved. That might be true of self-replicating machines. Will we combine 3D printing with in-situ resource utilization to build self-replicating space probes?

One aerospace engineer with expertise in space robotics thinks it could happen sooner rather than later. And that has implications for SETI.

Alex Ellery is a Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. Ellery is the author and co-author of many papers and articles on topics like 3D printing, in-situ resource utilization, self-replicating machines, and robotic exploration.

Ellery has published a new article on Cambridge Core titled “Self-replicating probes are imminent – implications for SETI.” In it, he talks about advances in 3D printing, self-replication, and robotics and says that we’re already building self-replicating machines, though they have their limitations. He also says that if we’re developing them, then ETIs—if any exist—should’ve developed them, too. He argues that SETI might be better focused on finding evidence of probes rather than scanning the sky for radio signals.

Ellery writes about a whole host of concepts familiar to Universe Today readers, for example, biomimicry and asteroid mining. He says that biomimicry can play an important role in self-replicating space probes dedicated to asteroid mining. “Self-replicating probes are an example of TRIZ (Teorija Reshenija Izobretatel’skih Zadach), a theory of inventive problem solving that matches biomimetic solutions to technological problems,” he writes.

Full article here:

https://www.universetoday.com/156730/well-be-building-self-replicating-probes-to-explore-the-milky-way-sooner-than-you-think-why-havent-etis/

The article linked here:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-astrobiology/article/selfreplicating-probes-are-imminent-implications-for-seti/2CB214D26020D497D48AE489756BEE77