Dust between the stars usually factors into our discussions on Centauri Dreams when we’re considering its effect on fast-moving spacecraft. Although it only accounts for 1 percent of the mass in the interstellar medium (the other 99 percent being gas) its particles and ices have to be accounted for when moving at a substantial fraction of the speed of light. As you would expect, regions of star formation are particularly heavy in dust, but we also have to account for its presence if we’re modeling deceleration into a planetary system, where the dust levels will far exceed the levels found along a star probe’s journey.

Clearly, dust distribution is something we need to learn more about when we’re going out from as well as into a planetary system, an effort that extends all the way back to Pioneers 10 and 11, which included instruments to measure interplanetary dust. Voyager 1 and 2 carry dust detecting instruments, and so did Galileo and Cassini, the latter with its Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA).

And I’m reminded by a recent news release from the New Horizons team that the Student Dust Counter (SDC) aboard New Horizons is making a significant contribution as it moves ever deeper into the Kuiper Belt. You’ll recall that the SDC played the major role in identifying what may be an extended Kuiper Belt in findings published in January (citation below). Alex Doner (University of Colorado Boulder) is lead author of the paper on that work. He serves as SDC lead:

“New Horizons is making the first direct measurements of interplanetary dust far beyond Neptune and Pluto, so every observation could lead to a discovery. The idea that we might have detected an extended Kuiper Belt — with a whole new population of objects colliding and producing more dust – offers another clue in solving the mysteries of the solar system’s most distant regions.”

Image: Artist’s impression of a collision between two objects in the distant Kuiper Belt. Such collisions are a major source of dust in the belt, along with particles kicked up from Kuiper Belt objects being peppered by microscopic dust impactors from outside of the solar system. Credit: Dan Durda, FIAAA.

We have to account for the variable distribution and composition of dust not only in terms of spacecraft design but also for fine-tuning our astronomical observations. Scattering and absorbing starlight, dust produces what astronomers refer to as extinction, dimming and reddening the light in significant ways. It’s a part of the cosmic optical background, which on the largest scale includes light from extragalactic sources as well as our own Milky Way. This background can tell us about galactic evolution and even dark matter if we know how to adjust for its effects.

Joel Parker (SwRI) is a New Horizons project scientist who notes that even as the craft continues to make observations within the Kuiper Belt (and the search for potential flyby targets continues), its instruments are also returning data with implications for astrophysics at large:

“New Horizons is uniquely positioned to make astrophysical observations that are difficult or impossible to make here on Earth or even from orbit. Many things can obscure observations, but one of the biggest problems is the dust in the inner solar system. It may not be obvious when you look up into a clear night sky, but there is a lot of dust in the inner part of the solar system. There is also a great deal of obscuration at certain ultraviolet wavelengths at closer distances due to the hydrogen that pervades our planetary system, but which is much reduced out in the Kuiper Belt and the outer heliosphere.”

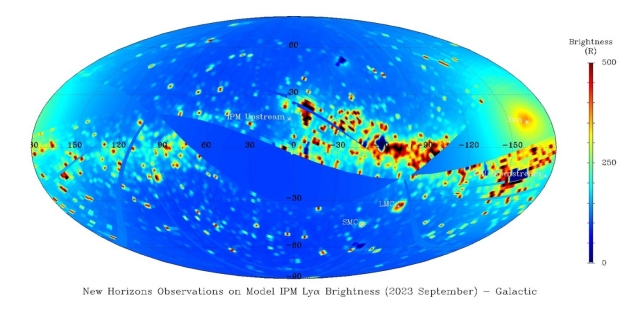

Image: New Horizons mission scientists and external colleagues are taking advantage of the New Horizons spacecraft’s position in the distant Kuiper Belt to make unique astrophysical and heliospheric observations. Alice, the ultraviolet spectrograph on the spacecraft, performed 75 great circle scans of the sky in September 2023, for a total of 150 hours of observations. These data focus on the light from hydrogen atoms in the ultraviolet Lyman-alpha wavelength across the sky as seen from New Horizons’ vantage point in the distant solar system. This map shows the data from the scans overlaid on a smoothed model of the expected Lyman-alpha background. (Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/SwRI).

We’ve recently talked about hydrogen-alpha transitions, which are a factor in astronomical observations (we saw this in the Project Hephaistos Dyson sphere papers). The Lyman-alpha transitions referred to above produce different emissions as electrons change energy levels within the atom, and are primarily useful for studies of the interstellar and intergalactic medium. So New Horizons is on point for helping us clarify how local dust levels may affect our observations of these distant sources.

Parker puts it this way:

“It’s like driving through a thick fog, and when you go over a hill, it’s clear. Suddenly, you can see things that were obscured. When you’re trying to look for a very faint light far outside our solar system or beyond our galaxy, that obscuration creates a challenge. If we measure how the ‘fog’ changes as we move farther out, we can make better models for our observations from Earth. With more accurate models, we can more easily subtract the effects of light and dust contamination.”

New Horizons records the cosmic ultraviolet background and maps hydrogen distribution as it moves through the outer regions of the heliosphere and eventually through the heliopause and into the local interstellar medium. This is going to be useful in telling astronomers something about the evolution of galaxies by yielding data on star formation rates as we learn how to remove the contaminating signature of interplanetary dust from our observations.

It’s fascinating to see how a single spacecraft can, as have the Voyagers, function as a kind of Swiss army knife with tools useful well beyond a single target. Successors to New Horizons will one day extend these observations as we learn more about dust distribution all the way out to the Oort Cloud.

The paper on a possible extended Kuiper Belt is Doner et al., “New Horizons Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter Observes Higher than Expected Fluxes Approaching 60 au,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 961, No. 2 (24 January 2024), L38 (abstract).

Surely, since dust is assumed to be generated by collisions it should be greatest near the plane of the solar system and much less far above or below it. Hence activities other than studies of that region should avoid it if possible.

Perhaps the advantage of being there is that most dust particles would be orbiting in the same direction, in that plane, so loitering out there would involve fewer collisions. Maybe that’s a consideration in looking for artifacts, too.

From the image caption: “Such collisions are a major source of dust in the belt, along with particles kicked up from Kuiper Belt objects being peppered by microscopic dust impactors from outside of the solar system.”

I wonder whether that’s true. It was all dust in the early solar system. The formation of KBO reduced the amount of dust by collecting it in larger bodies. Sure there are collisions of various types that increase dust, but it may be that over the eons we have reached an equilibrium between dust and KBO accretion.

“The dust between the stars”

Would make for a great title for a SciFi story! (Or even a horror story!)

——————————–

But yes, it’s great to hear that New Horizons (the fastest spacecraft ever launched by humanity, until 2023, when that record was over taken by Parker Solar Probe) is still doing amazing science, in terms of dust density in the outer regions of our solar system.

It also still has an active onboard telescope (LORRI) that still takes images of distant objects now and then. If I recall correctly it is the most distant telescope ever operated by humanity.

——————————–

But of course…

The question that a lot space fans wonder about is:

Will New Horizons ever be able to visit another object? It would be absolutely awesome if it could visit a 4th object (after it has already passed Pluto, Charon, and Arrokoth–the snow man object!).

Interestingly it still has a decent amount of propellant to change course, and possibly do a close flyby of another object if we get very lucky, but…

So far nothing within range… and my hope seems to be fading it will ever encounter something else?

Perhaps when the Vera Ruben Telescope goes online, they’ll discover a new object it can aim for?

We’ve got until the 2030’s to try to find something else for it, until the RTG runs out. (And assuming the remaining onboard propellant will still function until that time?)

If no suitable destination can be found for this probe, perhaps the best use for its remaining propellant is to move it as far out of the plane of the solar system as possible. I suspect the environment north and south of the ecliptic differs substantially from the plane itself, and those differences may hold clues as to how the solar system formed. I suspect that dust, gas, energetic particles and magnetic

fields vary in unexpected ways as a function of both distance from the ecliptic and from the sun.

The planetary alignments that allow these high probe gravity-assist velocities are so rare that this type of maneuver (to penetrate high ecliptic latitudes) should be considered as part of the planning of every mission that employs them.

That is a very good idea, Henry. Even a few degrees difference will magnify itself over time. Perhaps you can send this on to the New Horizons team, or at least see if they have already considered such a plan.

Another purpose the distant probe was supposed to serve after its main mission at Pluto was complete, which included sending all of its data back to Earth first, was to have a large information package ala the Voyager Interstellar Record transmitted to the probe and stored in its computers. See here:

https://www.planetary.org/articles/0424-new-horizons-one-earth-message

What concerns me is that I have not heard anything about this project in a while and their two (?) official Web sites appear to be no longer focused on their original subject. See here:

https://newhorizonsmessage.com/

http://oneearthmessage.org/

Does anyone know what has become of this effort, this One Earth Message? Why did it fall off the radar?

New Horizons definitely needs a fresh infusion of information about us and our world, as the project team decided not to bother with their own version of a Pioneer Plaque or Voyager Golden Record. What they did include can be read here:

http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html

The real irony is that all the NH team had to do was make a reproduction of the Pioneer Plaque and bolt it to the vessel. There would be little if nothing to change because even the diagram of the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes looks very similar to New Horizons!

https://www.planetary.org/articles/0120-the-pioneer-plaque-science-as-a-universal-language

Thankfully, there are some new organizations taking the idea of preserving our culture and presenting ourselves to other intelligences in the Universe seriously and have already taken real steps to ensure we will not completely vanish into the future. Here are two such groups…

Arch Mission Foundation:

https://www.archmission.org/

The Long Now Foundation:

https://longnow.org/

Great idea!

I like it.

Didn’t the IBEX guys think they had seen an accretion disk?

This before Planet 9 thought to perhaps be a gas giant mass black hole.

Same location?

Thanks, Larry.

The people who plan and support these missions often succeed in heroic measures to extend their utility and service for as long as possible. Unfortunately, the budgets eventually run out. Scientists and technicians must move on for the sake of their careers, and the funding must be directed to other, more critical missions.

Its sad, because the spacecraft may continue operating perfectly for decades, returning data faithfully, but there may be no one listening. The staffs and facilities

are tasked to newer, sexier projects (or dismantled and dispersed) and the brave little robots continue their endless fall into the void, silent running.

There is a lesson here, if we care to listen. Technology is capable of remarkable accomplishments, but sometimes it is very wasteful.