The solar wind is ever enticing, providing as it does a highly variable stream of charged particles moving out from the Sun at speeds up to 800 kilometers per second. Finding ways to harness that energy for propulsive purposes is tricky, although a good deal of work has gone into designs like magsails, where a loop of superconducting wire creates the magnetic field needed to interact with this ‘wind.’ But given its ragged variability, the sail metaphor makes us imagine a ship constantly pummeled by gusts in varying degrees of intensity, constantly adjusting sail to maintain course and stability. And it’s hard to keep the metaphor working when we factor in solar flares or coronal mass ejections.

We can lose the superconducting loop if we create a plasma cloud of charged particles around the craft for the same purpose. Or maybe we can use an electric ‘sail,’ enabled by long tethers that deflect solar wind ions. All of these ideas cope with a solar wind that, near the Sun, may be moving at tens of kilometers per second but accelerating rapidly with distance, so that it can reach its highest speeds at 10 solar radii and more. Different conditions in the corona can produce major variations in these velocities.

Obviously it behooves us to learn as much as we can about the solar wind even as we continue to investigate less turbulent options like solar sails (driven by photon momentum) and their beam-driven lightsail cousins. A new paper in Science is a useful step in nailing down the process of how the solar wind is energized once it has left the Sun itself. The work comes out of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), which is part of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA), and it bores into the question of ‘switchbacks’ in the solar wind that have been thought to deposit energy.

At the heart of the process are Alfvén waves, named after Hannes Alfvén (1908-1995), a Nobel-winning Swedish scientist and engineer whose work is at the heart of the discipline known as magnetohydrodynamics. What Alfvén more or less defined was the study of the interactions of magnetic behavior in plasmas. Alfvén waves move along magnetic field lines imparting energy and momentum that nourishes the solar wind. Kinks in the magnetic field known as ‘switchbacks’ are crucial here. These sudden deflections of the magnetic field quickly snap back to their original position. Although not fully understood, switchbacks are thought to be closely involved with the Alfvén wave phenomenon.

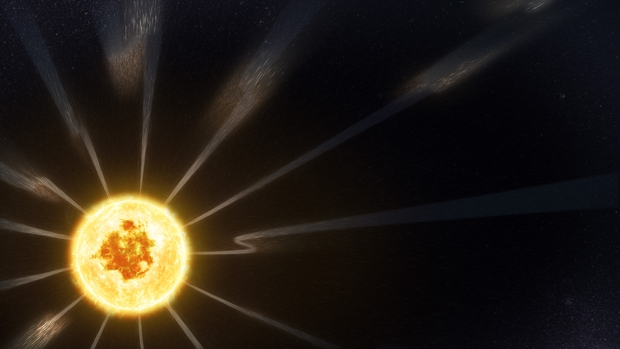

Image: Artist’s illustration of the solar wind flowing from the Sun measured by Parker Solar Probe near the edge of the corona and later with Solar Orbiter at a larger distance during a spacecraft alignment. The solar wind contains magnetic switchbacks, or large amplitude magnetic waves, near Parker Solar Probe that disappear farther from the Sun where Solar Orbiter is located. Credit: Image background: NASA Goddard/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez, Spacecraft images: NASA/ESA.

Data from two spacecraft have now clarified the role of these switchbacks. The Parker Solar Probe readily detected them in the solar wind, but data from ESA’s Solar Orbiter mission added crucial context. The two craft, one designed to penetrate the solar corona, the other working at larger distances, came into alignment in February of 2022 so that they observed the same solar wind stream in the scope of two days of observations. CfA’s Samuel Badman is a co-author of the study:

“We didn’t initially realize that Parker and Solar Orbiter were measuring the same thing at all. Parker saw this slower plasma near the Sun that was full of switchback waves, and then Solar Orbiter recorded a fast stream which had received heat and with very little wave activity. When we connected the two, that was a real eureka moment.”

So we had a theoretical process of energy movement through the corona and the solar wind in which Alfvén waves transported energy, but now we have data charting the interaction of the waves with the solar wind over time. The authors argue that the switchback phenomena pumps energy into the process of heating and acceleration sufficient to drive the fastest streams of the solar wind. Indeed, John Belcher (MIT), not a part of the study, considers this to be a ‘classic paper’ that demonstrates the fulfillment of one of the Parker Solar Probe’s main goals.

Such work has ramifications that will be amplified over time as we continue to investigate the environment close to the Sun and the solar wind that grows out of it. The findings will help clarify how future craft might be designed to take advantage of solar wind activity, but will also provide insights into the behavior of any sailcraft we send into close solar passes to achieve high velocity gravitational slingshots to the outer system. Always bear in mind that heliophysics plays directly into our thinking about the system’s outer edges and the evolution of spacecraft designed to explore them.

The paper is Rivera et al., “In situ observations of large-amplitude Alfvén waves heating and accelerating the solar wind,” Science Vol 385, Issue 6712 (29 August 2024), p. 962-966 (abstract).

Thanks for posting on this topic, Paul. My intuition tells me that such re-connection events will drive the clipper ships of the future piloted by quantum AI modeling the solar plasma and predicting time and place where switchbacks will occur. Always eager for more on this topic!

“quantum AI modeling the solar plasma”

Wow! Cool SF idea.

Alternatively, it might lead to finding ways to mitigate the solar wind. It is not unlike the problem faced by sailing ships having to not just deal with the winds (solar wind, but also the waves (solar photons). The solution was large steel ships powered by fossil fuels to avoid the limitations of wind power.

As photonic sailing is so useful, perhaps we need to build sails that are not affected by the solar wind when cruising close to the sun? Use the solar wind with electric and mag sails where it is more uniform and less turbulent. Or use the photons to power electric propulsion instead, as propellant is readily available in the system if exploited by infrastructure. The solar power collectors might be as large as the sails to deliver the needed power. For human spaceflight, we need effective shields to protect us from particle radiation, and charged particles could be deflected by magnetic fields rather than matter, reducing spacecraft mass and reducing the problem to the cosmic ray background.

While [solar] weather conditions are always good to know, we don’t have to live in tents if we can build sturdier structures.

https://astrobiology.com/2024/12/parker-solar-probe-has-touched-the-outer-reaches-of-a-star.html

Parker Solar Probe Has Touched The Outer Reaches Of A Star

By Keith Cowing

Press Release

NASA

December 29, 2024

Editor’s note: The Parker Solar Probe recently conducted a close fly-by of a star – our sun. This is the closest that any human object has ever gotten to any star. In so doing we will learn more about how our local star works. From an astrobiology perspective this is very important. How a star behaves with regard to the worlds that circle it can determine whether habitable conditions arise and whether a star can maintain these habitable conditions by virtue of its behavior long enough for life to arise and evolve.

Recently there has been great interest in M-dwarf or red dwarf stars. These are rather common, small cool, and often elderly stars that have been found to have planets similar in size to Earth. These worlds are some times within the habitable zone of that star. One example is the TRAPPIST-1 system.

But since an M-dwarf star is small, any worlds it has within its habitable zone will orbit very close to that star. M-dwarfs are known to often be active with large flares. Any stellar flares or other large energetic events could directly affect these close-in worlds thus making their habitability less than it might otherwise be.

As such, studying our own star can provide deep insights into how other stars i.e. those with potentially habitable worlds – might behave throughout their lifespan.

Operations teams have confirmed NASA’s mission to “touch” the Sun survived its record-breaking closest approach to the solar surface on Dec. 24, 2024.

Breaking its previous record by flying just 3.8 million miles above the surface of the Sun, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe hurtled through the solar atmosphere at a blazing 430,000 miles per hour — faster than any human-made object has ever moved. A beacon tone received late on Dec. 26 confirmed the spacecraft had made it through the encounter safely and is operating normally.

This pass, the first of more to come at this distance, allows the spacecraft to conduct unrivaled scientific measurements with the potential to change our understanding of the Sun.

“Flying this close to the Sun is a historic moment in humanity’s first mission to a star,” said Nicky Fox, who leads the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “By studying the Sun up close, we can better understand its impacts throughout our solar system, including on the technology we use daily on Earth and in space, as well as learn about the workings of stars across the universe to aid in our search for habitable worlds beyond our home planet.”

Parker Solar Probe has spent the last six years setting up for this moment. Launched in 2018, the spacecraft used seven flybys of Venus to gravitationally direct it ever closer to the Sun. With its last Venus flyby on Nov. 6, 2024, the spacecraft reached its optimal orbit. This oval-shaped orbit brings the spacecraft an ideal distance from the Sun every three months — close enough to study our Sun’s mysterious processes but not too close to become overwhelmed by the Sun’s heat and damaging radiation. The spacecraft will remain in this orbit for the remainder of its primary mission.

“Parker Solar Probe is braving one of the most extreme environments in space and exceeding all expectations,” said Nour Rawafi, the project scientist for Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), which designed, built, and operates the spacecraft from its campus in Laurel, Maryland. “This mission is ushering a new golden era of space exploration, bringing us closer than ever to unlocking the Sun’s deepest and most enduring mysteries.”

Close to the Sun, the spacecraft relies on a carbon foam shield to protect it from the extreme heat in the upper solar atmosphere called the corona, which can exceed 1 million degrees Fahrenheit. The shield was designed to reach temperatures of 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit — hot enough to melt steel — while keeping the instruments behind it shaded at a comfortable room temperature. In the hot but low-density corona, the spacecraft’s shield is expected to warm to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

The spacecraft’s record close distance of 3.8 million miles may sound far, but on cosmic scales it’s incredibly close. If the solar system was scaled down with the distance between the Sun and Earth the length of a football field, Parker Solar Probe would be just four yards from the end zone — close enough to pass within the tenuous outer atmosphere of the Sun known as the corona. — NASA/APL

“It’s monumental to be able to get a spacecraft this close to the Sun,” said John Wirzburger, the Parker Solar Probe mission systems engineer at APL. “This is a challenge the space science community has wanted to tackle since 1958 and had spent decades advancing the technology to make it possible.”

By flying through the solar corona, Parker Solar Probe can take measurements that help scientists better understand how the region gets so hot, trace the origin of the solar wind (a constant flow of material escaping the Sun), and discover how energetic particles are accelerated to half the speed of light.

“The data is so important for the science community because it gives us another vantage point,” said Kelly Korreck, a program scientist at NASA Headquarters and heliophysicist who worked on one of the mission’s instruments. “By getting firsthand accounts of what’s happening in the solar atmosphere, Parker Solar Probe has revolutionized our understanding of the Sun.”

Previous passes have already aided scientists’ understanding of the Sun. When the spacecraft first passed into the solar atmosphere in 2021, it found the outer boundary of the corona is wrinkled with spikes and valleys, contrary to what was expected. Parker Solar Probe also pinpointed the origin of important zig-zag-shaped structures in the solar wind, called switchbacks, at the visible surface of the Sun — the photosphere.

Since that initial pass into the Sun, the spacecraft has been spending more time in the corona, where most of the critical physical processes occur.

“We now understand the solar wind and its acceleration away from the Sun,” said Adam Szabo, the Parker Solar Probe mission scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This close approach will give us more data to understand how it’s accelerated closer in.”

Parker Solar Probe has also made discoveries across the inner solar system. Observations showed how giant solar explosions called coronal mass ejections vacuum up dust as they sweep across the solar system, and other observations revealed unexpected findings about solar energetic particles. Flybys of Venus have documented the planet’s natural radio emissions from its atmosphere, as well as the first complete image of its orbital dust ring.

So far, the spacecraft has only transmitted that it’s safe, but soon it will be in a location that will allow it to downlink the data it collected on this latest solar pass.

“The data that will come down from the spacecraft will be fresh information about a place that we, as humanity, have never been,” said Joe Westlake, the director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “It’s an amazing accomplishment.”

The spacecraft’s next planned close solar passes come on March 22, 2025, and June 19, 2025.

By Mara Johnson-Groh

Astrobiology, Space Weather, Heliophysics