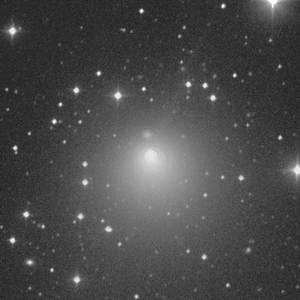

Evidently discovered by French astronomer Pierre Méchain in 1786, Comet Encke was the first periodic comet to be found after Halley’s Comet. It was named after Johann Franz Encke, who first calculated its orbit. It comes into play this morning because it is considered the source of at least part of the Taurid meteor shower, which is the subject of new work out of the University of Maryland that has implications for our thinking about asteroid and comet mitigation.

Image: This is an image of short-period comet Encke obtained by Jim Scotti on 1994 January 5 while using the 0.91-meter Spacewatch Telescope on Kitt Peak. The image is 9.18 arcminutes square with north on the right and east at top. The integration time is 150 seconds. Credit: NASA.

The Taurids show up in October and November as Earth encounters this stream of debris in an area of its orbit thought to conceal possibly dangerous asteroids. The American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences annual meeting was the occasion for the announcement of the work earlier this week, as noted by Quanzhi Ye at UMD, who summarized the finding:

“We took advantage of a rare opportunity when this swarm of asteroids passed closer to Earth, allowing us to more efficiently search for objects that could pose a threat to our planet. Our findings suggest that the risk of being hit by a large asteroid in the Taurid swarm is much lower than we believed, which is great news for planetary defense.”

The UMD team, working with colleagues at the University of Western Ontario and the University of Washington, Seattle and Poolesville High School in Maryland, used data from the Zwicky Transient Facility telescope, a widefield astronomical survey at Palomar Observatory in California. The idea was to search for objects at least a kilometer in diameter left behind by a much larger source.

The result is heartening, as Ye explains:

“Judging from our findings, the parent object that originally created the swarm was probably closer to 10 kilometers in diameter rather than a massive 100-kilometer object. While we still need to be vigilant about asteroid impacts, we can probably sleep better knowing these results.”

Image: An image of the Taurid meteor shower taken in 2015 by Czech amateur Martin Popek, who produced this striking composite recording fireballs occurring roughly once an hour from the direction of Taurus. Credit: Martin Popek.

Sky surveys like those conducted at the Zwicky Transient Facility track potentially dangerous near-Earth objects, and the ZTF will be used to conduct follow-up studies on the Taurids in coming years. The unusually dusty Comet Encke is relatively large for a short-period comet, with a nucleus of 4.8 kilometers, and it is believed to have experienced significant and likely ongoing periods of fragmentation.

Each new result charting potential danger zones for our world is useful as we work out the likelihood of possible future impacts. While that hunt continues, so too does the effort to learn more about changing the orbit of a potential impactor, as witness the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), a NASA mission that impacted the asteroid moon Dimorphos in 2022 and clearly disrupted the object. The European Space Agency’s Hera mission, launched on October 7, will assess the DART results when it arrives in two years (see A spaceship punched an asteroid — we’re about to learn what came next in the latest issue of Nature for more on this).

The original orbit of Dimorphos was oblate but became much more stretched out (prolate) after the collision with DART. The impact shortened the period of the asteroid’s orbit around its primary by 33 minutes. So we’re learning about at least one way to nudge an asteroid orbit, with other techniques still on the table for future study. Asteroid mitigation will drive near-Earth space technologies forward and move deeper into the system as we add to our catalog of potential impactors, one of which may eventually pose a threat significant enough to prompt action.

The Younger Dryas impact and the Taurid meteor stream.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1751696X.2024.2373876#abstract

See section six.

18 Sep 2024

Ancient Apocalypse: The Americas | Series two of Graham Hancock’s series to be released on Netflix on 16th October.

In this second series produced by ITN Productions, Graham goes to the Americas to search for evidence supporting his hypothesis that an advanced civilization was lost to history in the series of cataclysms that brought the last Ice Age to an apocalyptic end between 12,800 and 11,600 years ago.

The sensationalist trailer for Hancock’s new series: Ancient Apocalypse. Et tu, Keanu? [Best stick to genre fiction movies.]

One can get a taste of Hancock’s speculations from his book titles which includes “The Mars Mystery” which is adjacent to Hoagland’s nonsense about the face on Mars due to the perception of a face from low-resolution Viking picture of a geologic feature in Cydonia, Mars which was dispelled by later higher resolution images of the feature. Our Western imagination of the “Man in the Moon” is similar based on our eyesight and is similarly dispelled by telescope images of the Moon. The same idea in fiction is the desert mouse seen by the Fremen on Arrakis’ 2nd moon, Muad’dib.

Hancock’s works show what can result from “going down the rabbit hole” when ideas are not rigorously tested, debated with evidence, and peer-reviewed.

There is risk with disrupting a rubble pile heading towards Earth. Although the main threat may be averted by an intervention of this kind, of the enormous number of small particles that are ejected many will continue on their Earth-bound trajectory. That won’t pose a catastrophic threat but for the growing population of small LEO satellites (and growing) many may be hit. Perhaps that’s an acceptable trade-off. As for ISS and other human spacecraft, there will be increased risk.

The suggestion that a nuclear blast with the X-ray emission deflecting an asteroid might just work.

Whether this works for a real asteroid TBD.

The link: Nukes (Yes, Nukes) Could Save Earth from an Asteroid

I don’t think X-rays are going to stop anything of this size, an impactor that is 30 miles across. Australia seems to have the largest number and best preserved impact craters on the planet. Taking the size of Australia as about 1.5 percent of the surface area of the world that would mean an impact of this size would occur every 7.5 million years. Most in the ocean or places where erosion would obliterate the impacts. So maybe we better start looking for large impactors coming from deep space instead of the local merry go round…

MAPCIS, or the Massive Australian Precambrian-Cambrian Impact Structure, is a proposed colossal impact crater located in Central Australia, with an estimated diameter of about 600 kilometers. Believed to have formed around 541 million years ago during the transition from the Precambrian to the Cambrian period, this ancient structure could hold the key to understanding significant geological and biological events in Earth’s history.

The impact that created MAPCIS was likely caused by an asteroid up to 50 kilometers in diameter, striking the Earth at a dramatic angle and unleashing unimaginable energy. This event may have contributed to the tectonic rifting between the North and South Australian Cratons and possibly influenced the eruption of the nearby Kalkarindji Large Igneous Province, a massive volcanic event. The discovery of high-pressure minerals like lonsdaleite and the detection of iridium anomalies within the region provide compelling evidence of an extraterrestrial impact, making MAPCIS a fascinating subject of ongoing scientific research and exploration. Join me as we dive into the mysteries of MAPCIS and explore how this ancient impact might have shaped the world as we know it.

The Massive Asteroid Impact in Central Australia.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHlov3BeLAY

Earth had Saturn-like rings 466 million years ago, new study suggests.

https://www.space.com/ancient-earth-ring-system-asteroid-breakup

A global glacial period caused by the shadow of this ring system may have obliterated earlier impacts on much of the planet.

A very good reason to go back to our moon since all large impact their are frozen in time, we could very well be in for a number of surprises. Cheap robotic AI craft massed produced could do it much faster then manned missions. Maybe even solar powered ion engines that could land take drill samples and analyse it’s age before flying on to the next large impact site on the moon.

https://www.space.com/ancient-earth-ring-system-asteroid-breakup

Earth Had a Ring Like Saturn’s for Millions of Years, and Its Shadow Triggered an Ice Age.

The Ordovician period witnessed an explosion of biodiversity known as the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, and some scientists have suggested that the increase in meteorite impacts could have played a role in this phenomenon.

https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2024/09/earth-had-a-ring-like-saturns-for-millions-of-years-and-its-shadow-triggered-an-ice-age/

https://www.universetoday.com/170220/meteor-showers-may-one-day-help-protect-humanity/

Meteor Showers May One Day Help Protect Humanity!

December 29, 2024

by Mark Thompson

For centuries, comets have captured our imagination. Across history they have been the harbingers of doom, inspired artists and fascinated astronomers. These icy remnants of the formation of the Solar System hold secrets to help us understand the events nearly 5 billion years ago. But before these secrets can be revealed, comets have to be studied and to study them they need to be found.

A team of researchers have developed a technique to hunt down comets based upon data from meteor showers and to assess if they pose any threat to us here on Earth!

Comets are objects that orbit the Sun like the planets but their orbits are usually more elliptical. They are composed of dust, gas and water ice and often called ‘dirty snowballs.’ Many comets are part of, or were a part of the Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt. These distant regions of space house many of the Solar System’s icy bodies.

On occasions, interactions between the bodies in the clouds can send chunks in toward the inner Solar System transforming the dormant chunks of rock and ice into the comets we recognise.

Driven by heating from the Sun, the ice immediately sublimates into a gas giving rise to a comets familiar fuzzy coma and tail. Contrary to popular belief, the tail of a comet doesn’t stream out behind the comet as it travels through space, instead, it always points away from the Sun pushed in that direction by the Solar Wind.

Geysers of dust and gas shooting off the comet’s nucleus are called jets. The volatile material they deliver outside the nucleus builds the comet’s coma. Credit: ESA/Rostta/NAVCAM

Comets are categorised as either short period comets or long period with the latter group having an orbit of more than 200 years. Due to their long orbits, scientists fear that one will be on a collision course with Earth and go completely un-noticed until it is too late. The risk of this occurrence is of course incredibly small but the impact could be catastrophic to life on Earth.

A team of astronomers led by Samantha Hemmelgarn from the Northern Arizona University has published a paper in Planetary Science Journal where they explain their technique for identifying threats from long period comets using data from meteor showers.

“This research gets us closer to defending Earth because it gives us a model to guide searches for these potentially hazardous objects,” Hemmelgarn said. Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through the debris left behind by a comet. The team has studied 17 meteor showers that are associated with long period comets and calculated where the parent comet should be in space.

Using the path of the meteor showers, the team can assess the likelihood that a long period comet could pose a threat over its future orbits. In the test cases, the model accurately predicted the comet locations including its direction and speed of travel. This provides the opportunity for astronomers to hone their search around the sky looking for long period comets rather than hope one might be spotted through automated searchers that scour the whole sky.

The obvious benefit is that early identification of a comet on a collision course with Earth means that there is more time to develop a plan for our defence. There is nothing yet that provides any concern for astronomers but the next impact event of extinction level, may be millions of years away. The team hope that their work and model will help to provide humanity with the earliest warning of potential impacts.

https://news.nau.edu/hemmelgarn-comets/

Dec 12, 2024 Research & Academics

How to find a comet before it hits Earth

Q: How do you find a comet that could pose a threat to Earth but hasn’t passed our planet in the last 200 years or more?

A: You look for its footprint.

This is the basis of research led by Samantha Hemmelgarn, a first-year doctoral student in Northern Arizona University’s Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science. In a study published in Planetary Science Journal in November, she and her co-authors, including adviser Nick Moskovitz from Lowell Observatory, used data from meteor showers—the “footprints” left by comets—to pinpoint where these comets are in the sky and determine whether they pose a threat to Earth.

“This research gets us closer to defending Earth because it gives us a model to guide searches for these potentially hazardous objects,” Hemmelgarn said.

The paper is online here:

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/PSJ/ad8346