Given our intense scrutiny of planets around other stars, I find it interesting how little we know even now about the history of our own Sun, and its varying effects on habitability. A chapter in an upcoming (wildly overpriced) Elsevier title called The Archean Earth is informative on the matter, especially insofar as it illuminates which issues most affect habitability and how the values for these vary over time. It’s also a fascinating look at changing conditions on Venus, Earth and Mars.

We know a great deal about the three worlds from our local and planetary explorations, but all too little when it comes to explaining the evolution of their atmospheres and interior structures. But it’s important to dig into all this because as Stephen Kane, director of The Planetary Research Laboratory at UC-Riverside and colleagues point out, we seem to be looking at the end state of habitability on both Mars and Venus, meaning that our explorations of these worlds should yield insights into managing our own future. Powerful lessons are likely to emerge, some obvious, some obscure.

The chapter title is “Our Solar System Neighborhood: Three Diverging Tales of Planetary Habitability and Windows to Earth’s Past and Future” (citation below), from which this:

Resolving the numerous remaining questions regarding the conditions and properties of our local inventory of rocky worlds is… critical for informing planetary models that show how surface conditions can reach equilibrium states that are either temperate and habitable, or hostile with thick and/or eroded atmospheres.

Given the challenges of working at the Venusian surface, Mars is particularly valuable as a case study, a world that has evolved through a period of habitability (is this true of Venus?) and undergone interior changes including cooling, not to mention loss of atmosphere. The more we learn about the evolution of rocky worlds, the more we will be able to apply these discoveries to planets around other stars. We’re in search of models, in other words, that show how planets can reach equilibrium as habitable or hostile.

The Archean eon (roughly 4 to 2.5 billion years in extent) takes us through the formation of landmasses, Earth’s early ‘reducing’ atmosphere (light on oxygen but rich in methane, ammonia, hydrogen carbon dioxide) and all the way to the emergence of life. So we have plenty to work with, but for today I want to focus on one aspect of habitability that we haven’t discussed all that often, the changes in the Sun since Earth’s formation. Our G-class star had to progress through a protostar stage lasting, perhaps, 100,000 years or more, then a T-tauri phase likely lasting 10 million years. There’s a lot going on here, including shedding angular momentum as the young Sun expels mass, slowing its rotation rate and producing a powerful solar wind.

The Sun’s arrival on the main sequence follows, and we’re immediately involved in a singularly vexing astronomical puzzle. The consensus seems to be that the early main sequence Sun was only about 70 percent as bright as the star we see today. That being the case, how do we account for the fact that water appears early in Earth’s history in liquid form on the surface? The expectation of a frozen world is a natural one, yet liquid water at the surface seems to have been available for some four billion years.

Image: The landscape during the early Archean could have looked like this: small continents on a planet mostly covered by oceans, illuminated by the much fainter young Sun, and with a Moon that appears larger in the sky because of its smaller distance to Earth. Credit: Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Infant stars in the T-tauri phase are quite bright, getting their energy primarily from gravitational contraction. When they reach the main sequence and hydrostatic equilibrium sets in, they are considerably dimmer. The Sun enters the main sequence undergoing stable hydrogen fusion, which drives its luminosity. The notion that the Sun was dimmer early in the main sequence derives from models showing a solar core that is less dense and contains less helium. As core density increases as hydrogen is converted to helium, the resultant heating accounts for the steady brightening since.

Carl Sagan was an early voice in exploring the ‘faint young Sun’ problem in relation to liquid water and the matter is still controversial, although a number of possibilities exist. The authors believe the logical way to explain why a fainter star could provide conditions for liquid water on the surface is through the presence of greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide, although the influence of methane is problematic unless, as in recent papers, scientists invoke planetary impacts or a primitive photosynthetic biosphere that amplifies the methane cycle. Whatever the case, mechanisms to regulate habitability are clearly crucial. From the chapter:

It is remarkable that Earth seems to have become habitable within its first few hundreds of millions of years and maintained that state seemingly without interruption to the present. This persistence is a testimony to the power of feedbacks that drive and regulate climate evolution with notable success on Earth in comparison with our Solar System neighbors Venus and Mars. Most important is the silicate weathering negative feedback, whereby rising temperatures coinciding with a warming Sun are offset by increasing rates of CO2 consumption through continental weathering, which is enhanced under warmer, wetter conditions. And we can thank diverse plate tectonic processes and their roles in such carbon cycling for this sustained thermostatic capacity over much of our history.

But let’s return to that very early Sun emerging onto the main sequence. Factors affecting a young star’s luminosity include the rotation rate of the star, and here we have little information (the Sun’s rotational rate in this era is uncertain, although some evidence suggests that it was a slow rotator). But the earliest planets could have been pummeled by radiation in this early state for tens or even hundreds of millions of years, which would have had a dire effect on any atmospheres they had formed. Note this:

…the intensity of the emission depends on the rotation rates of the stars, which are highly variable (from observation of stars in <500 Myr old stellar clusters). “Fast rotating” young stars can reach about a hundred times the rotation rate of the modern Sun, whereas moderate rotators could rotate at about ten times that rate and slow rotators would reach a few times the Sun’s rotation rate (Tu et al., 2015). Corresponding luminosities for young stars in the EUV and X-ray range of the spectrum can reach on the order of a 1000 times present mean solar luminosity at similar wavelengths for fast rotators, a few 100 times for moderate rotators and between a few tens to a hundred times the reference for slow rotators.

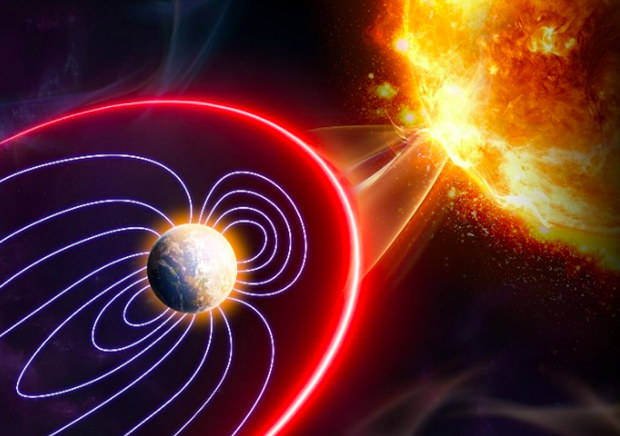

We’ve looked before at both the solar wind and solar flares as factors influencing planetary atmospheres and interacting with their magnetic fields, perhaps stripping atmospheres entirely in the case of M-class planets orbiting tightly around their primary. Atmospheric escape takes two forms, the first being thermal loss, where atoms are accelerated to the point where they reach escape velocity. Intense radiation is one but not the only way of doing this, but the effect on an atmosphere can be dire.

Other processes that can adversely affect an atmosphere include ions being accelerated along magnetic field lines by the solar wind or photochemical reactions. You would think that these effects would vary with distance from the star, but as the authors note, the loss estimates for Mars, Venus and Earth are relatively similar, and this despite the major differences in the makeup of the atmospheres on these planets and their magnetic field situation. Mars lacks a protective magnetic field today but seems to have had one in the past. Venus likewise lacks an intrinsic magnetic field like that produced on Earth through its convective dynamo, although interactions between the solar wind and the CO2-rich atmosphere do produce a weak magnetic effect.

Image: Diagramming a solar flare encountering Earth’s magnetosphere. Credit: Jing Liu (Shandong University, China and National Center for Atmospheric Research in the U.S).

As to the Sun, variations in the solar magnetic field over time are assumed given that a faster spinning star would have produced higher levels of magnetic activity. Today’s solar cycle, eleven years long, is the result of the magnetic reversal cycle of the Sun. The twists and tangles of magnetic field lines during this cycle cause sunspot activity to peak and then decline as the north and south magnetic poles reverse. The Sun’s magnetic field strengthens and weakens during the cycle, with effects apparent in the solar wind itself and in spectacular events like coronal mass ejections.

If we back out to the largest timescales, the variations in the Sun’s magnetic field indicate a much stronger field early in the Sun’s evolution, coupled with a (presumed) faster stellar rotation rate. From the standpoint of habitability, that tells us that ultraviolet and X-ray flux along with the solar wind has been decreasing with time. We’re probably talking about orders of magnitude difference in UV and X-ray radiation, but the authors point out that the intensity of emission depends upon the rotation rate of stars, and there is much we still have to learn about both this and luminosity.

The high degree of uncertainty on the Sun’s rotation rate and temperature affect our estimates of the ultraviolet at X-ray emissions our star would have produced, and thus the impact of this flux on the atmospheres of the terrestrial planets. Enlarging our field of view to exoplanets, it’s clear that the more we can piece together about the Sun’s early history, the more we can learn about the atmospheres and habitability of planets around the various spectral types of stars. Kane and team see the Sun as a template for planetary evolution, which makes heliophysics crucial for the study of astrobiology.

This study, then, homes in on the factors that need to be clarified as both heliophysics and exoplanetary science move forward. Even the closest planet to us presents formidable challenges, and the authors’ discussion of Venus is well worth your time. Here we have a world whose young surface – relatively uniform in the range of 250 to 1000 million years old – makes digging into its more remote past all the more difficult. Evidence can only be indirect at this stage of planetary exploration. We’re lucky to have Mars within reach as we widen the study of planetary formation to worlds other than our own.

The chapter in the Elsevier book is Kane et al., “Our Solar System Neighborhood: Three Diverging Tales of Planetary Habitability and Windows to Earth’s Past and Future,” available as a preprint. Two Sagan papers on the faint young Sun paradox are notable: Sagan & Mullen, “Earth and Mars: Evolution of Atmospheres and Surface Temperatures”, Science 177 (1972), 52 (abstract) and Sagan & Chyba, “The early faint sun paradox: Organic shielding of ultraviolet-labile greenhouse gases,” Science 276 (1997), 1217 (abstract). You might also want to look at Ozaki et al., “Effects of primitive photosynthesis on Earth’s early climate system,” Nature Geoscience 11 (2018), 55-59 (abstract), which offers up a methane solution for the faint young Sun.

From the post, it is not clear if the fainter young sun is also potentially emitting much more shorter radiation – UV and X-rays. If so, isn’t this a problem for the “warm surface pond” location for abiogenesis?

The assumption of a faint sun resulting in a frozen surface has been mitigated by assuming a larger H2 envelope to warm the planet. I am now wondering if the X-rays and UV increased photolysis, creating more H2 , but paradoxically oxidizing the CH4 to CO2, so both increasing and decreasing the GHG effect.

Lastly, given the Earth was very hot from accretion and bombardment, could a frozen surface overlay a liquid ocean kept warm by the heat of the rocks. with the surface ice acting as an insulating surface, even as the albedo increased?

Whatever the surface conditions, it seems to me that the case is strengthened for a deep ocean origin of life if it truly appears so quickly after the formation of the Earth.

Alternatively, could warmer Venus have been the site of abiogenesis, with its life migrating to Earth on the solar wind and taking hold once the surface was warm enough for exposed liquid oceans? This would not change the apparent genomic data for the age of LUCA. Unfortunately what hope is there for understanding Venus’s early state?

Will exoplanet data help resolve the problem as we could get data for a range of stellar ages and planetary conditions

Earth was rotating faster in the past and therefore it’s magnetic field was stronger. This would not have any effect on the UV radiation. What happens is that the UV is what actually made life possible, the photo dissociation of molecular oxygen O2 into atomic oxygen or two O1 which is combined with ozone. O1 plus O2 equals O3 or ozone. Consequently is does not matter it there was stronger UV. It still would be stopped by the O3 ozone in the upper atmosphere, Right now nitrogen and oxygen and ozone stop the ultra violet, x rays and gamma rays. Nitrogen is though to be of biotic origin. An atmosphere of mostly carbon dioxide would stop the x rays and gamma, but not ultra violet which is stopped by ozone.

@Geoffrey

There is no evidence that free O2 was present in the early atmosphere, so there is no ozone. Any O2 produced would react with methane to oxidize the carbon to CO2, otherwise we would have a disequilibrium CH4/O2 atmosphere – a biosignature.

Water will block UV, suggesting that abiogenesis would be deep enough to avoid the UV destroying organic molecules.

If the source of free N2 is a sign of life, then the remaining N2 in the Martian atmosphere is the remnant of life on Mars, rather than primordial. Is that a hypothesis you are claiming? If so, then how do you account for the dense N2 atmosphere of Titan?

Quote by Alex Tolley: “Water will block UV, suggesting that abiogenesis would be deep enough to avoid the UV destroying organic molecules” Water does block some UV, but not enough to protect life even underwater. Source Open AI chat GPT. Water mostly absorbs in the infra red portion of the EM spectrum which is why water vapor is a greenhouse gas. We have to assume that the depth that life was born was great enough to block the UV, but not the visible light.

I think the N2 on Mars is from chemical or abiotic origin because it is a very small amount compared to the total percentage in the atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Some of it may have been from life and due to the jeans escape and low gravity on Mars it escaped. If live evolved on Mars it was not there long enough to make enough N2 to dominate it’s atmosphere like Earth.

According Open AI chat GPT one hundred million years after Earth’s collision with Theia, the gas with the highest percentage was carbon dioxide so N2 was the second component. The oxygen I was meant was caused by life. The evidence is banded iron formations BIF’s, The great oxidation event GOE, river beds and Sulfur isotopes. Ibid. What I thought was interesting is the same thing that is harmful to life, the ultra violet radiation helped create life, the photolysis of diatomic or molecular oxygen O2 into atomic oxygen, or two O1. atoms. One O1 combines with molecular oxygen O2 to make O3 ozone.

@Geoffrey

Let me counter your argument about an ozone atmosphere that supports, rather than destroys life.

Firstly, we are talking about a prebiotic Earth in the Hadean. This was the condition that sets the stage for abiogenesis.

The consensus is that this early atmosphere was mildly reducing. IOW, there was an excess of reducing agents like hydrogen over oxidizing agents like oxygen and sulfur. Any free oxygen would be reduced back to water. Photolysis from UV would create some O2, but an O2 atmosphere could only remain if the H2 was removed, e.g. by escape, leaving the O2 behind. If O2 did start to accumulate for any reason, the reduced gases, methane, and ammonia would be oxidized to CO2 and NO/NO2. IOW, O3 would not be formed to create a UV shield.

Prebiotic atmosphere.

Regarding water-blocking UV. UV wavelengths are from 100-400 nm, starting at the end of the violet visible spectrum. This webpage on water shows the absorption spectrum for water. The minimum absorption is around 300nm and then rapidly rises orders of magnitude higher than even IR. So at best, a narrow UV band can penetrate the water column as far as the bluest light. In reality, even the most transparent parts of the ocean have sufficient light for photosynthesis down to 200m, and the very dim twilight zone reaches down to 1000m. The average depth of the oceans is 4000m, and the ocean ridges with hot vents are below 1000m. IOW, UV cannot penetrate to these depths, allowing organic molecules to persist, and accumulate in the rocks around the vents. The young sun was fainter, so these depths would change accordingly, but even a higher %age of UV would still be blocked, providing a safe environment for chemotrophic bacteria. Yes, there might be an issue for early photosynthetic bacteria as the zone where they could photosynthesize may also have been subject to stronger UV, but clearly, that was insufficient to prevent photosynthesizers from evolving.

Regarding nitrogen. Best estimates for the prebiotic nitrogen level is 1/2 to 2x the present N2 amount, i.e. that the atmospheric N2 in the prebiotic atmosphere wqas primordial. Yes, bacteria are involved in the nitrogen cycle, but we are talking about the prebiotic period.

The banded iron formations appear when life had evolved oxygenic photosythesis at least a billion years after the Earth formed, and if the genomic analysis is correct, perhaps a billion years after the LUCA appeared. Life was wholly aquatic until at least 500 mya, and by the time complex life had appeared, the atmospheric O2 was high enough to provide the UV shield which allowed plants and animals to eventually emerge onto the land.

Quote by Allex Tolley: “Let me counter your argument about an ozone atmosphere that supports, rather than destroys life.” Ozone can be damaging to cells especially in smog that can damage lung cells. We agree on that. As far as Ozone being a protective shield from harmful UV radiation I don’t think that idea is debatable according to atmospheric and astrophysics which are based on the first principles of physics.

Quote by Alley Tolley: “The minimum absorption is around 300nm and then rapidly rises orders of magnitude higher than even IR” This statement is false according to the principles of atmospheric physics. I also don’t see any evidence in the link you posted that supports your statement. Atmospheric physics is complicated and one should not jump too fast conclusions.

According to Open AI Chat GPT Ozone O3 is a much more effective absorber than water vapor H2O. Quote by Open AI Chat GPT: “Absorption Efficiency: “Due to its structure, ozone is orders of magnitude more efficient at absorbing UV light than water vapor, making it a crucial component in protecting life from harmful UV radiation. Ozone can absorb UV light roughly 10,000 to 100,000 times more effectively than water vapor, especially in the critical UV-B and UV-C bands which is an order of magnitude larger than water vapor.”

UVB and UBC bands are the shorter wavelength and more harmful UV radiation than UVA. Water vapor has a weaker absorption in the UV range than Ozone. Water absorbs UV strongly in mostly in the 100 to 200 nm range The harmful UVC range is 100 to 280 nm which is absorbed by Ozone including the UVB band. Water absorbs a little at 200 to 280nm. Ibid. According to Open AI Chat GPT water vapor is less efficient at absorbing UV because it is a smaller molecule than Ozone. This is quantum mechanical and based on atomic physics and spectroscopy. Every atom and molecule has a specific and distinct energy level different than the other atoms and molecules as seen in the table of elements in chemistry. It is the ground state from zero to one in the quantum energy level jumps in the electron that determine what wavelength in the electromagnetic spectrum that an element or molecule will absorb which are called spectral lines, the actual energy levels in a particular atom which are distinct and unique like a finger print. Consequently, the idea that Ozone absorbs harmful UV more efficiently than water vapor is not considered to be debatable by physicists, astrophysics, chemists, scientists, etc. since it is based on the first principles of physics.

A more detailed explanation on the size of the molecule: The larger ozone molecules have chemical bonds that are harder to break apart due to their bond strength than the smaller water vapor molecules. Larger molecules have more bonds, or “strong complex bonding arrangements” and absorb better without breaking apart. Ozone continually absorbs UV and stays in the air longer than water vapor. Free molecular oxygen O2 and the atomic oxygen O1 recombine after UV dissociation, so there is an dynamic oxygen ozone cycle or replenishment. Larger molecules have wider range of electronic and vibrational energy levels and therefore absorb a broader range of UV wavelengths. Ibid.

UV radiation not only is involved in making more ozone and protecting life, it is thought to make complex chemical reations in water and make the building blocks of life, amino acids, fats, which is what RNA is made. “quote from Open AI Chat GPT: “Experiments have shown that when water and basic building blocks like hydrogen cyanide and formaldehyde are exposed to UV light, they can form amino acids and nucleobases—key components of proteins and DNA. This process could have occurred on early Earth in shallow pools or near hydrothermal vents, where UV light could penetrate” and “Formation of Amino Acid Precursors: Amino acids may have formed through UV-driven reactions involving simple gases like ammonia, methane, and water, similar to the conditions used in the famous Miller-Urey experiment. UV light can break chemical bonds and allow these atoms to recombine in new ways, potentially forming amino acid precursors that eventually led to proteins.”

Very interesting.

As we collect data on the geological and atmospheric history of our planet – and its sun, it would certainly lead one to wonder how, by actually existing now, we have somehow rode atop a very unstable wave . Because, if we were baked like a cake, the 4.5 giga year preparation scheme must have been unseemly at the least with such elaborate preliminaries. Unless there is some other element in our kitchen of our birth that makes this a likely outcome.

In the American Association for Advancement of Science (AAAS) journal “Science”, the work of planetary scientist Robert Hazen was reviewed this week, based on the premise that evolution could be considered as a process beyond simply biology, but in inorganic processes such as planetary and even stellar evolution ( p. 608 8 NOVEMBER 2024 • VOL 386 ISSUE 6722). Indeed, in that last case, there are textbooks and classes with that name, though seldom bringing up Charles Darwin. But in this Hazen did. That Darwin did not apply his premise far enough.

Having listened to Hazen’s lectures over the past decade in the context of the early solar system and the settings for life’s origin, it does seem that he has a point. At the very least, he does highlight how the Moon, Mars and Earth’s chemical complexity contrasts in ascending complexity. Clearly the presence of life on Earth has shaped its surface and interior to some depth. With Mars it might have been more complex in this context eons before with some evidence eroded away. And Hazen a decade ago would have called its complexity intermediate. But the Moon has remained just a few dozen chemical compounds. We don’t have expectations of a Rover finding evidence of an ancient sea, save like Sea of Storms or Clouds smoothed by lava flows.

Hazen, as the article indicates, that in recent years, beside noting the solar system contrasts, contends that this rolling tendency toward chemical and atomic complexity might merit consideration as a fundamental law with an arrow indicator pointed by time from the big start. Otherwise, it is hard to explain why the infall of orbiting dust and gas just happened to result in you and me and our fair city. And likely nowhere else.

Perhaps this idea floats more easily if we do not mention the opposing concept of entropy – but I am sure that Hazen is well aware of its process role as well.

However, introducing this universal tendency to complication as an interpretation of what we see locally in the solar system with collapse from largely hydrogen clouds into stars, dust rings and planets. Now and then it is noted that a mineral wells back up due to plate tectonics, or an enrichment arrives on a comet or meteorite, the absence of which could have delayed another geological era.

It’s not necessarily just in time delivery for manufacture. But it does seem built into a larger system than a self absorbed Earth.

And with a planet as large as Neptune or Jupiter, we still have no idea what kind of things could be produced in such a cauldron, warmed enough and sustained at some stratum – a biochemical equilibrium of some sort? In those instances, it would seem that if life arose, the odds would be for it to remain in isolation owing to gravity and depth – unless it obtained remarkable features to allow its exit from that environment. Mars precursors for Earth have been argued. But if one were a martian, would not Jupiter and the asteroids have some grip on your notion of geological history? Likely more than the Earth. But attributing life on Earth to earlier life on Mars, shifts the whole argument back to one more planet, like placing a turtle under an elephant in some earlier cosmic display.

What is also persuasive about Hazen’s argument is that this growth of complexity is phased. If the sun or star and its surrounding cloud of gas, dust and proto planets is not fit for habitation for anything eukaryotic, then there are still a lot of precursor processes going on which could produce bio-favorable results

– later. For most of geological time, the Earth was uninhabitable for “you or me”.

Only about a tenth of its history appears to devoted to life with many cells

or specialized nuclei. Having developed to address the opportunities of an immediate environment…Then why didn’t the microbes just leave it at that?

The complication imperative?

So it leaves one to wonder about the structure of a certain domain for advance of complexity or the reverse of entropy …Where should we draw the line? The Earth? The solar system to its widest frontiers? The similar portions of the galaxy. Of many other galaxies? The Drake equation was focused largely on the communications task between us and radio broadcasting LGMs. But so many of those intermediate factors rest on the answer to the question that Hazen has come around to argue for in positive terms. At the very least, not everything about our origin had to be against nearly insurmountable odds, but perhaps due to pervasive features of the cosmos we live in.

And during our stay on this planet and its near environs we dream of complicating the cosmos just a bit further.

The idea that minerals increase in complexity, but with an ever smaller fraction of possible structures is not unlike the idea of Assembly Theory that Cronin uses as a way to distinguish life from non-life, and Hazen’s work on detecting the difference between life’s organic chemistry and abiotic chemistry.

However, I would point out that the last stage of Hazen’s classification of minerals is the biotic stage, that is minerals formed due to life.

It seems to me that several ideas are converging on this, perhaps starting with complexity theory and emergence. Kauffman was doing work on self organization of autocatalytic sets as part of abiogenesis, as well as the constraining of cycle numbers from random networks, mostly with an average of 2 connections.

While Hazen’s classification of minerals with time was very new, I am not sure that his claim of a “a new physical law” is new, but rather an application of prior research to mineralogy and extending it into other domains.

We might be looking in the wrong direction when considering the presence of liquid water on Earth’s surface 4 billion years ago. At that time, our Moon was only about 15,000 miles away—or even less when accounting for the 4,000 miles to the Earth’s surface. Much of that water may have been subducted deep into the Earth due to impacts and the massive tidal effects caused by the Moon, which created a gigantic, planet-wide conveyor belt. Volcanic activity would have been extremely high, likely containing significant amounts of water, similar to what we see at mid-ocean ridges. In essence, Earth would have resembled a “super-Earth” and may have been internally heated enough to be characterized as a steam planet.

With the above note, one could modify “habitability with a young sun” to something concerning a young Earth emerging into a close binary. The givens of such a

scenario are not immediately clear to me. But accepting the notion that the moon was the result of a collision with the Earth and re-coalescence into a planetary body from something like a ring, it must have been a very early occurrence – if that is the story. Here on Earth it is hard to imagine where to search for the geological record of such an impact and the convulsion afterwards. Perhaps it might even be regarded as one big irregular event of the process. And it sure poses a problem for modeling exo-Earths since it is hard to invoke a lunar birth event in each of their formative processes – and subsequent evolution.

Then after the dust and rings clear, we still have to address stellar variability early on.

…With all that activity up or down the street from it, would you suppose that Mars or Venus felt any impact from that? For example, some rather invariant martian highlands retaining a geological record of that time. By some measures Mars habitability might have preceded that of the Earth’s due to such considerations. But by some measures too ( plate tectonics) it is less dynamic and a longer record.

We do get a few chunks of Mars, distinguishable in the Antarctic or Sahara, likely not so ancient. But just possibly, Mars might have some impact debris from the Earth from way back.

We have an incredible resource right here—a living fossil—so there’s no need to look to Mars. The moon has recorded events from very early in our solar system’s history, while Earth has lost 99 percent of its early geological record. Deep within the layers of the moon are details of the early sun, preserved for eternity.

However, visualizing the early formation of the only double planet can be challenging, as there are no comparable locations in the solar system. We do understand the oceanic ridge system that spans the deep oceans of Earth. Four billion years ago, this ridge would have encircled the Earth in the same path where the moon now orbits. The moon’s immense gravity would have raised this ridge 100 miles into the air, forming an arc from the north to the south poles. These poles would have marked the origin of the continental crust, akin to Antarctica but composed of solid rock. Today, we observe the remnants of this structure in the large islands and island chains located east of the main continental masses.

You might consider this pure science fiction, but it’s worth exploring what AI can generate since our perspective is quite limited.

I had no idea that René Heller, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research had developed the same idea four years ago.

Habitability of the early Earth: liquid water under a faint young Sun facilitated by strong tidal heating due to a closer Moon.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12542-021-00582-7

“Tidal heating as a geothermal heat source might have helped to sustain enhanced mantle temperatures, for instance by driving hydrothermal fluid circulation in early Earth’s crust. This interpretation would be compatible with the previously stated “hydrothermal pump” concept, which asks for an internal heat source and strong forces in the crust of the Archean Earth to explain the presence of 3.49-Gyr-old black chert veins of the Dresser Formation (Western Australia). A unified model that includes geophysical, atmospheric, tidal, and astrophysical effects could be able to resolve the longstanding faint-young-Sun paradox.”

Here is another article that has a very good YouTube video of the size and distance of the moon from 4.5 billion years ago to the present.

How the Moon helped mold the Earth into a habitable potato.

https://astrobites.org/2021/12/16/how-the-moon-molded-the-earth-into-a-habitable-potato/

“Tidal heating might also have had some knock-on effects, like increasing the amount of erupting volcanoes on the early Earth as a way to help lots of CO2 get into the atmosphere for greenhouse warming. This makes it just one of many interconnected processes other than just radiation from a host star affecting whether a planet has conditions suitable for life.”

When it comes to the faint young sun paradox, what is more amazing than Earth having liquid water from a very early age, but that Mars did as well.

But, I don’t see too much of a paradox here. I think liquid water under conditions of low insolation can be explained by a thicker atmosphere and the adiabatic lapse rate.

If Earth had a 4 bar atmosphere, the surface temperature would be 120 °C warmer than the 1 bar level (dry lapse rate) 60°C warmer wet lapse rate.

Earth has 3 bar of Nitrogen like Venus. Only 2/3 of a bar is in the atmosphere. The rest is mineralized or dissolved in the ocean. Mineralization requires an oxidizing environment, which would not have been early Earth.

I was also reading paper which modeled the last global ice age 800 mya. When the planet went into snowball, Earths volcanoes added CO2 at a steady linear rate until at 100 mbar, the ice melted. It appears that the carbonate-silicate cycle is extremely powerful at adjusting an Earthlike planet’s temperature to around room temperature over a long period.

Add to that, we don’t know how much of Earth’s early atmosphere was stripped away by the young sun, and a reducing atmosphere that contains a variety of gases like H2S that can contribute to global warming and you’ve got it covered.

The inventory of nitrogen on Earth should be similar to Venus at around 3 to 4 bar. On Venus it is free but on Earth it is mainly in the mantle and sediments/minerals now due to life. Perhaps nitrogen fixing organisms evolved later than though of allowing a much thicker atmosphere for longer allowing for more insulation and thermal storage from the greenhouse gases.

The mineralogy of Mars 4 bya implies a quite oxidizing atmosphere. This implies a fair amount of atmospheric loss due to UV disassociation of water molecules and preferential Hydrogen loss.

Earth at this time was mildly reducing, so unless Earth had a thick H/He atmosphere in its formative days (It was a Hycean planet) then Earth’s oxidation state puts an upper limit on the amount of atmospheric striping it underwent.

There may be another explanation for how the Earth was kept warm during the period of the faint young Sun. Both the Sun and the Earth were rotating faster and had larger magnetic fields at that time. There may have been a direct coupling between the Earth and the Sun, similar to the flux tube interaction seen between Jupiter and its moon Io. In this scenario, solar flares and sunspots might have been more concentrated near the poles, much like what is observed in fast-rotating stars. This linkage with Earth’s magnetic field would be more likely to occur in a large Earth-sized planet with a significant magnetic field, as opposed to planets without such features.

Since our solar system does not exhibit this unique interaction between a large, Earth-sized planet and a strong magnetic field, we would need to create a model to explore this concept further. For instance, when intense solar flares strike Earth, they can damage large-capacity transformers and energize specific types of rocks. The heating associated with the substantial electrical currents linked to these flux tubes could raise the temperatures in the Earth’s mantle and magma chambers.

Additionally, water, being an excellent conductor, plays a role in this process; significant internal reservoirs of water are found in rocks around 700 kilometers below the surface. Therefore, the early Earth may have resembled a steam kettle, and even today, some volcanoes are influenced by substantial rainfall.

Michael, your steam kettle analogy may be a good one. I was reading (I can’t remember where) that there is a significant amount of water, oceans worth, deep in the crust of Mars, mainly as ice; but there’s a substantial liquid layer as well.

So it appears that as the internal heat of a planet goes away, its water migrates down from the surface, or alternately, a planet with a lot of internal heat boils its internal water upwards, which condenses on the surface.

Here’s something that may help: the Moon’s passage through the Earth’s magnetic tail could contribute to the presence of lunar water near the Moon’s poles. Four billion years ago, the Earth was much closer to the Moon, which would have allowed more material from the Earth’s atmosphere to be deposited on the lunar surface. This material is likely buried deeper in the lunar ice.

Additionally, major impacts on Earth, such as the one that occurred 66 million years ago, could have sent material to the Moon as well. We can hope to recover this record by drilling into craters that may hold answers in the lunar south pole.

Earth’s atmosphere may be source of some lunar water.

https://www.uaf.edu/news/earths-atmosphere-may-be-source-of-some-lunar-water.php

I think we’re missing a larger picture here. Carbon on the early Earth would have been, for the most part, a volatile element. Today, about a quarter of the sedimentary rock on Earth is carbonates, which have been laid down over more than two billion years. If you imagine bombarding the surface of the Earth with planetesimals, burning every fossil fuel deposit, turning every limestone bed into unslaked lime, that would cause far more global warming than humanity has yet dreamed of doing. But in addition, early Earth would have had much more hydrogen: instead of being in the form of CO2, much of this carbon would have existed as CH4 – a greenhouse gas so potent that legislators worry about the amount venting from wells and released by cows breaking wind.

While the anthropic principle no doubt has a large role, I think there should have been some homeostasis in the regulation of Earth’s early temperature, because the hotter and thicker the atmosphere, the easier it is to lose hydrogen atoms to space.

For the Earth’s early, i.e. Hadean, after the Earth formed and the surface was very hot and the atmosphere was likely several bars and reducing in nature. I don’t think homeostasis is the right term for a process that is not disimilar to a pan of boiling water cooling to room temperature.

The formation of carbonates is from both the carbon and biological cycles, which are homeostatic processes, but did not start until there were oceans and continents, and later, life. So this started in the late Hadean and Archaean. [unless that is what you meant by “early”. If so, I apologize for this comment].

Well, I was fumbling around… in my mind there are two models. In the “pan cooling” model, say, 30% more atmosphere at the beginning means 30% more atmosphere and correspondingly higher temperatures when life becomes prevalent. In the “homeostasis” model, the same increased atmospheric pressure at the beginning ends up having no net impact on the atmospheric pressure when life becomes prevalent. In the first model, you can suppose Earth is picked out from a range of other planets because it happened to be where life evolved (which is surely true anyway); in the second, our sort of life seems like it may be favored by the rules of the game. My guess is the second model is closer to the truth, but I don’t know.