It’s not often that I highlight the work of anthropologists on Centauri Dreams. But it’s telling that the need to do that is increasing as we continue to populate the Solar System with human artifacts, which are after all the province of this discipline. I’ve often wondered about the fate of the Apollo landing sites, originally propelled to do so by Steven Howe’s novel Honor Bound Honor Born and conversations with the author ranging from lunar settlement to antimatter. Long affiliated with Los Alamos National Laboratory, Howe is deeply involved in antimatter research through his work as CEO and co-founder of Hbar Technologies.

In my conversations with Howe almost twenty years ago while writing my original Centauri Dreams book, he was asking what would happen if commercial interests decided to exploit historical sites from the early days of space exploration. The question is still pertinent. Imagine Armstrong and Aldrin’s Eagle subjected to near-future tourists prying off souvenirs or putting footprints all over the original tracks left by the astronauts. Some kind of protection is crucial before technology in the form of cheap access to the lunar surface becomes available, and that may be a matter of decades more than centuries. The point here is to get the policies in place before the contamination can occur.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 is ratified by over 100 nations, but while offering access for exploration to all nations doesn’t address the preservation of historical sites. UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention does not apply to sites off-planet, while NASA’s 2011 protection guidelines offer useful ‘best practice’ solutions for protecting sites, but these are entirely voluntary. The Artemis Accords are bilateral agreements that offer language toward the protection of historical sites, but again are non-binding. So the Moon stands as an obvious example of an about to be exploited resource for which we lack any mechanisms to protect places future historians will want to examine.

Or think about Mars, as Kansas anthropologist Justin Holcomb does in a paper just published in Nature Astronomy. As we are increasingly putting technologies on the surface, we are building up yet another set of historical sites that will be of interest to future historians. This is important stuff even if the equipment is quickly rendered inert and soon obsolete, and it’s worth taking an anthropologist’s view here – we’ve learned priceless things about the past through the study of what a civilization thought of as materials fit only for the garbage dumps of the time. What will future scholars learn about the great era of Mars exploration that is now well underway?

“These are the first material records of our presence, and that’s important to us,” says Holcomb. “I’ve seen a lot of scientists referring to this material as space trash, galactic litter. Our argument is that it’s not trash; it’s actually really important. It’s critical to shift that narrative towards heritage because the solution to trash is removal, but the solution to heritage is preservation. There’s a big difference.”

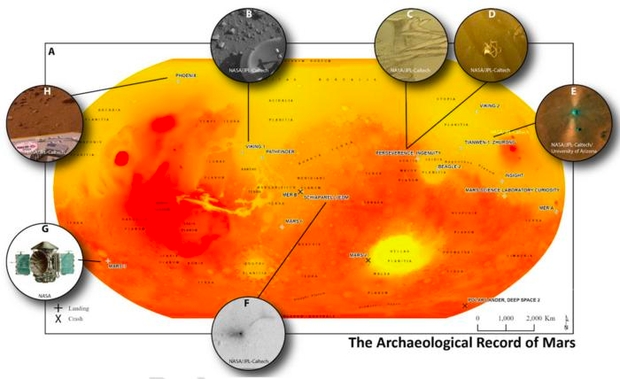

Image: Map of Mars illustrating the fourteen missions to Mars, key sites, and examples of artifacts contributing to the development of the archaeological record: (B) Viking-1 lander; (C) trackways created by NASA’s Perseverance rover; (D) Dacron netting used in thermal blankets, photographed by NASA’s perseverance rover using its onboard Front Left Hazard Avoidance Camera A; (E) China’s Tianwen-1 lander and Zhurong rover in southern Utopia Planitia photographed by HiRISE; (F) the ExoMars Schiaparelli Lander crash site in Meridiani Planum; (G) Illustration of the Soviet Mars Program’s Mars 3 space probe; (H) NASA’s Phoenix lander with DVD in foreground. Credit: Justin Holcomb.

In August of 2022, the Mars rover Perseverance encountered debris scattered during its landing a year earlier. Our Mars rovers repeatedly have come across heat shields and other materials from their arrival, while the wheels of the Curiosity rover have left small bits of aluminum behind, the result of damage during routine operations. Perseverance dropped an old drill bit in 2021 onto the surface as it replaced the unit with a new one. We can add in entire landers, intact but defunct craft like the Mars 3 lander, Mars 6 lander, the two Viking landers, the Sojourner rover, the Beagle 2 lander, the Phoenix lander, and the Spirit and Opportunity rovers. A 2022 estimate of spacecraft mass sent to Mars totals almost 10,000 kilograms (roughly 22,000 pounds), with 15,694 pounds (7,119 kilograms) now considered debris as the material is non-operational.

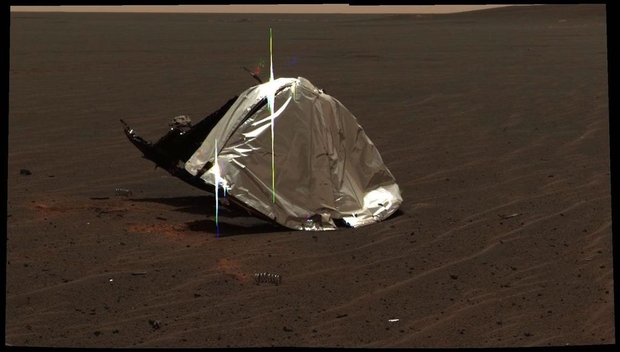

Image: This image from Opportunity’s panoramic camera features the remains of the heat shield that protected the rover from temperatures of up to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit as it made its way through the martian atmosphere. This two-frame mosaic was taken on the rover’s 335th martian day, or sol, (Jan. 2, 2004). The view is of the main heat shield debris seen from approximately 10 meters away from it. Many rover-team engineers were taken aback when they realized the heat shield had inverted, or turned itself inside out. The height of the pictured debris is about 1.3 meters. The original diameter was 2.65 meters, though it has obviously been deformed. The Sun reflecting off of the aluminum structure accounts for the vertical blurs in the picture. The image provides a unique opportunity to look at how the thermal protection system material survived the actual Mars entry. Team members used this information to compare their predictions to what really happened. Credit: NASA.

The human archaeological record on Mars began in 1971 with the crash of the Soviet Mars 2 lander. The processes that affect human artifacts in this environment are key to how they degrade with time, and thus how future investigators might study them. We’re in the area now of what is known as geoarchaeology, which has ripened on Earth into a sub-discipline that analyzes geological effects at various sites. Holcomb points out that Mars has a cryosphere in the northern and southern latitudes where ice action would alter materials even faster than Martian sands. But don’t discount those global dust storms and dune fields like the one that will likely bury the Spirit Rover.

So we have many sites to protect from future human activities as well as a need to catalog the locations of debris that will disappear to view through natural processes over time. This is satisfyingly long-term thinking, and I like the way Holcomb describes extraterrestrial artifacts (left behind by us) in terms of our own past:

“If this material is heritage, we can create databases that track where it’s preserved, all the way down to a broken wheel on a rover or a helicopter blade, which represents the first helicopter on another planet. These artifacts are very much like hand axes in East Africa or Clovis points in America. They represent the first presence, and from an archaeological perspective, they are key points in our historical timeline of migration.”

Migration. Think of humans as a species on the move. Outward.

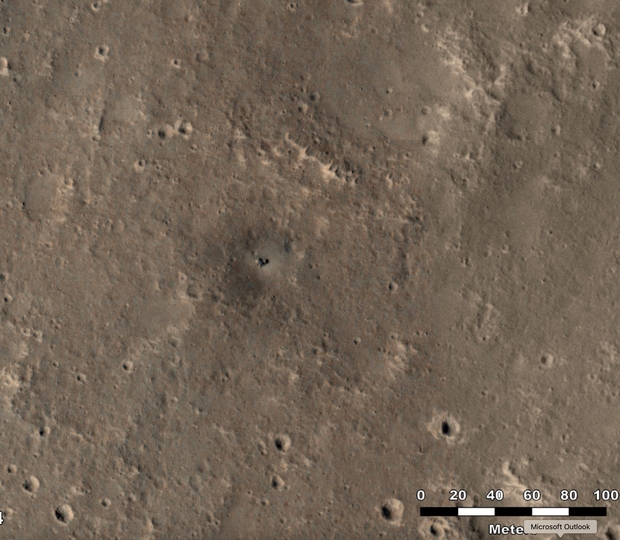

Image: Impact and its aftermath. What would a future anthropologist make of the materials found at this site? And how would it affect a future history of human exploration of another world? Credit: NASA.

In terms of mission planning, there is a pathway here. It would be best to avoid operations in sites where previous technologies were deployed, just as we wrestle with issues like those tourists on the Moon. Holcomb argues that we need to develop our methodologies for cataloging human materials on other planetary surfaces, and it’s obvious that we want to do that before such materials become prolific. So perhaps we should start seeing our space ‘debris’ on Mars as the equivalent of those Clovis points he mentioned above, which are markers for the Clovis paleo-American culture.

It always seems unnecessary to do analysis like this until the need surfaces with time, by which point we have let much of the necessary spadework remain undone. But on a broader level, I’m going to argue that thinking about the long-term stratigraphy of space exploration is another way we should engage with the reality of our species as multi-planetary. For that is exactly what we are headed for, a species that begins to explore its neighbors and perhaps establishes colonies either on them or in nearby orbits. That this process has already begun is obvious from the deluge of data we have already accumulated from the Moon all the way out into the Kuiper Belt.

Image: A historical site in context. Seen at the center of this image, NASA’s retired InSight Mars lander was captured by the agency’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter using its High-Resolution Imagine Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on Oct. 23, 2024. The images show how the dust field around InSight – and on its solar panels – is changing over time. Sites like this will inevitably be obscured by such a rapidly changing planetary surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona.

We need to stop being so parochial about what we are engaged in. Let’s be optimistic, and assume that humanity finds a way to keep migration going. The ancient middens that are nothing more than garbage dumps for early cultures on Earth have shown how valuable all traces of long vanished cultures can be. We need to preserve existing sites on other worlds and carefully ponder how we handle explorations that can, as they did in the American west, turn into stampedes. That we are talking here about preservation over future centuries is just another reminder that a culture that survives will necessarily be one that pays respect not only to its growth but to its history.

The paper is Holcomb et al., “Emerging Archaeological Record of Mars,” Nature Astronomy (16 December 2024). Abstract.

I’ll go with Indiana Jones here: “it belongs in a museum!” to be viewed by the public and studied by scientists. All except for Apollo 11, which should be protected in place, as depicted in Andy Weir’s book, Artemis.

The Moon is much more special than anywhere else, being the first place that humans have walked on (besides Earth!) and since it has no weather, the Apollo site can last for millions of years, while on Mars, everything is being slowly being degraded by blowing sand.

As the Director of The Viking Mars Missions Education and Preservation Project, the only dedicated organization to the preservation of Viking, this is a topic we have discussed since the seventies, but it has been “quieter” than other topics, for a variety of reasons, probably each of us with our own reasoning. However this topic (Space Archeology) is not new, and is beginning to venture out into more broad circles.

Your timing and curiosity and ideas are fabulous, and welcome as we build an international body to address exactly the things you mention (and more).

The lack of enforceability is a huge issue, as is the limited and elite nature of groups forming to discuss these issues.

There are a variety of players in the growing field, many of whom want to control the direction this moves in. But to some of us it is a bigger question, which is why a framework is necessary to assess articles that might be considered for preservation. That has already begun, and will be discussed at the upcoming AIAA SciTech Conference in Orlando in January where we are hosting a Panel of some of the experts, following another Summit on exacting this topic that since is us attended at Udvar-Hazy in DC.

However, again, the need for his to be international, is imperative, which is why the framework being developed is exactly that, and if done well, will be representative and dynamic.

For folks interested in understanding the Framework, feel free to reach out to us at info@thevikingpreservationproject.org

And hopefully some of your readers and you will join us at the Conference!

A pleasure to hear from you, Dr. Tillman. Thanks so much for the informative comment!

I must confess I’m not a PhD, but I’m always grateful to learn and share with others with similar interests!

source: Surveyor 3

NASA wasn’t quite so careful with the heritage of lunar artifacts back then – astronauts tramping over the site and taking parts back to Earth. At least it was somewhat recorded – but will the records be preserved?

A wider issue is the status of satellites in orbit. especially LEO. There are still some old satellites that have historical value. Yet the sheer number of satellites and the risk of making that orbit dangerous to pass through increases daily, and that is before Kessler Syndrome creates a real hazard. We will eventually start to sweep up debris and dead satellites. Should some satellites be left in their orbits for historical reasons, or retrieved for space museums? Should we create a “futuristic midden” of dead satellites and satellite pieces for posterity? I think that the value of some of these artifacts should be retrieved through sales to collectors to help pay for cleanup and stimulate collection efforts. [Unlike fossil dinosaurs, we track orbiting artifacts and therefore should be able to detect if any are being stolen for wealthy collectors.]

As for Mars, we may have to plan more quickly than we expected. However, I am more concerned with contamination of the surface before we explore it for signs of life. That exploration might have to be done away from any human settlement[s], and preferably by robotic instruments. What I do want is some very long-term storage of artifacts and records for posterity so that this era doesn’t become another “dark age”. This will require secure storage and records kept in an easily accessible form, preferably not just as electronic data which we have learned is quickly obsoleted and near impossible to read [c.f. Apollo video tapes.]

ACC wrote an amusing short story about Venusians trying to interpret the visuals of a short piece of film from a Disney cartoon. No soundtrack was decoded. [“History Lesson” (1949)].

Alex Tolley said on December 18, 2024 at 13:18:

“A wider issue is the status of satellites in orbit. especially LEO. There are still some old satellites that have historical value.”

The satellites in geosynchronous orbit at over 22,000 miles up will last for millions of years in space if left untouched. Artist Trevor Paglen created an art project mirroring the Voyager Interstellar Record and placed it aboard a comsat sent there in 2012 when he discovered how long these human artifacts will last at that altitude:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2013/01/18/the-last-pictures-contemporary-pessimism-and-hope-for-the-future/

Although not in the same orbits as the comsats, LAGEOS 1 is high up enough that it will remain circling Earth for 8.4 million years. This is why Carl Sagan was inspired to design and have placed this plaque inside the golf ball-shaped satellite for future recipients:

https://lageos.gsfc.nasa.gov/Design/Message_to_the_Future.html

In regard to Surveyor 3 and Apollo 12’s mission to it in 1969, you may find this relevant piece of interest:

https://www.drewexmachina.com/2019/11/25/the-apollo-12-visit-to-surveyor-3-a-preview-of-space-archaeology/

Hi Paul –

thanks for the great entry !

I think there’s a units error in the discussion of the mass of human-made material on mars; see below.

the first kg/pounds conversion checks out, but the second one leaves me wondering which value is correct.

> … spacecraft mass sent to Mars totals almost 10,000 kilograms (roughly 22,000 pounds), with 5,694 pounds (7,119 kilograms) now considered debris …

Looks like the original source left off a figure. I’ve just corrected 5,694 to the accurate 15,694. Thanks for spotting this.

Press release:

https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1068112

NASA press release on monitoring the InSight Mars lander via MRO:

https://www.nasa.gov/missions/insight/nasa-mars-orbiter-spots-retired-insight-lander-to-study-dust-movement/

News from 2013 on the possible finding of the Mars 3 lander, also via MRO:

https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/has-the-mars-3-lander-beenfound/

Preserving human artifacts on the Moon:

https://www.space.com/moon-spacecraft-prevent-destroy-apollo-artifacts

https://www.salon.com/2019/07/19/its-time-to-talk-about-preserving-monuments-on-the-moon/

https://daily.jstor.org/should-the-moon-landing-site-be-a-national-historic-landmark/

https://ideas.ted.com/nasas-efforts-to-protect-important-heritage-sites-on-the-moon/

Space is the place to preserve humanity:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2013/01/18/the-last-pictures-contemporary-pessimism-and-hope-for-the-future/

It’s litter other than, perhaps, a few items. We can’t help it yet but when we have the opportunity we should clean it up. The valuable items can, as Derek said, be housed in a museum, or just stored. Further, we can’t sweep away our tracks on worlds without erosion. I don’t see the problem with tracking over the old tracks.

We have the ability to leave a better legacy than random artifacts and litter from animals and prehistoric humans: information. That will be far more useful to historians than preserving robot tracks. If humanity self destructs and is unable to propagate durable information and artifacts, maybe it doesn’t matter.

In regard to calling the debris we have left on other worlds as “litter”, it may help to know that archaeologists often find more useful – and truthful – data about past cultures in digging through a society’s refuse piles than any of their official records or monuments.

Just think of the search for alien life: If we found the equivalent of a food wrapper left by an ETI, just to use an example, science would be thrilled as for the moment we have zero confirmed evidence of the existence of any life beyond Earth.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/the-space-archaeologist-studying-the-junk-humans-leave-throughout-the-cosmos-2/

https://www.thetimes.com/uk/science/article/space-junk-isnt-pollution-its-archaeology-says-professor-7mfdh8vjw?msockid=295f0603348667a51b4e15a235c56636

Has anyone been able to find the Soviet Mars 3 probe? The first successful landing on Mars on December 2, 1971. The details on Mars 2 and Mars 6 makes me wonder if they might have made it to the surface but did not survive the impact…

Michael C Fidler said on December 18, 2024 at 22:52:

“Has anyone been able to find the Soviet Mars 3 probe?”

From my list of links above, I included this 2013 piece on the possible finding of the Soviet Mars 3 lander:

https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/has-the-mars-3-lander-beenfound/

The issue with the Soviet Mars landers is that they tend to resemble boulders from a distance due to their design. What helped in finding Mars 3 was its parachute, which was not completely buried by Martian sand. I have yet to see if there has been further confirmation of this find.

Mars 2 and 6 both likely crashed, so depending upon how serious their impacts were, they may have left a debris field that would be even harder to differentiate from the surrounding rocks. Mars 6 was functioning as it descended, so there is a chance it may be somewhat intact.

This is also the issue with finding the early Soviet Luna landers, which their Mars landers’ design were based on, as they also resemble boulders from a distance. We know that Luna 9 and 13 made it to the lunar surface in one piece.

Speaking of lunar landers, I hope LRO can find Surveyor 4 as it may have landed intact in 1967. The probe’s signal disappeared just before landing. This may have been due to an unexpected explosion, or Surveyor 4 completed the landing sequence in one piece. Finding that probe will finally let us know its ultimate fate.

https://www.drewexmachina.com/2017/07/14/surveyor-4-the-impact-of-a-low-probability-event/

I found this on the search for Mars 6:

https://spaceref.com/science-and-exploration/nasa-mro-image-of-mars-search-for-soviet-mars-6-lander-2/

What’s interesting is the link at the bottom of the article. It links to the HiRise imaging lab and if you tap the top image it brings up a much larger image of the area of the search. The bottom map shows the outline of the image and what looks like an ancient riverbed where the Mars 6 landed…

Very interesting where all the water and atmosphere went on Mars; https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/news/mars-missing-water-atmosphere

It is interesting that the lost atmosphere has also been found. I’m hoping we can drill to where the H2O is liquid and look for any extant life. 20 km is a deep hole to drill for, but it might be reduced somewhat by starting at a low point, and perhaps at a latitude where the H2O is nearer the surface, or residual heat spots have raised the depth of liquid H2O. If there is life elsewhere in the solar system, Mars is still the best, most accessible, place to look.

Maybe…

Mars 3

All of this just makes me sad that the ISS will likely be sent to the ocean floor. Understandable due to the costs of maintaining its orbit and the possible Kässler effect if it gets hit by something, but nevertheless it would be nice if its orbit could be boosted and it be used as a museum of sorts.

This also reminds me of posts some years ago regarding the Voyager craft and a possible last hurrah with an attempt at using the remaining fuel to change course slightly ajust before they are switched off. Someone suggested we should go and recover them once we have the tech to do so, and put them in a museum back on Earth. I’d much rather leave them be and march on on their final course. At most we could send a craft with cameras to find them and keep pace with them, sending back pictures of our first little pioneers out of the solar system.

Here is the Centauri Dreams post on redirecting Voyager before it runs out of power you were referring to:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2015/04/21/voyager-to-a-star/

As for recovering the Voyager probes, or Pioneer 10 and 11 or New Horizons – and don’t forget their final stages, which are even bigger than these vessels – I think we should leave them to their destinies of being found by beings other than terrestrial. Either that or let them go long enough so that anyone from this planet in the distant future will truly appreciate having a human artifact from the near beginning of the Space Age.

Besides, look what might happen if we let aliens find them…

https://www.orionsarm.com/eg-article/49f9b4b02ce26

https://www.orionsarm.com/eg-article/47c1b07834a5f

Here is a Soviet video about the Mars 2 and 3 landers, complete with their little rovers they did not reveal to the West until 1990:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=SCqiG3xciC4

Here are two more videos on the Soviet missions to Mars:

https://youtu.be/knDT0iqo878?si=AinMLGt4wUzzGAYR

And…

https://youtu.be/xltW2G60GCs?si=yINy3MR78Wp37jgR

A Rosetta stone of sorts on the moon (or on a passing interstellar wanderer) would be more valuable than random hardware that will mean nothing to people in a 1000 (or even in a 100) years….

I guess the trouble I have with the moon landings was the backdrop. It wasn’t a noble bid to explore and understand, though these were the end products,

tesh said on December 19, 2024 at 3:11:

“I guess the trouble I have with the moon landings was the backdrop. It wasn’t a noble bid to explore and understand, though these were the end products.”

If this helps in your feelings about what the Apollo astronauts brought to and left on the Moon, among a number of culturally relevant artifacts such as a message disc from Apollo 11 and a Judeo-Christian Bible placed on the Apollo 15 Lunar Rover, the Apollo 12 mission has a small art museum tucked into one of the legs on its LM descent stage:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moon_Museum

A very informative legal view on preserving artifacts on the Moon:

https://www.mjilonline.org/preserving-humanitys-history-on-the-moon/

Here is a NASA document from 2011 with recommendations (nothing legally binding yet, unfortunately) for future lunar explorers on how to properly handle and deal with any historical human artifacts they come across on the Moon:

https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/nasa-usg-lunar-historic-sites-reva.pdf

There are already several Lunar Libraries on the Moon with 30 million pages of human data, with hopefully more to follow:

https://www.archmission.org/spaceil

https://www.archmission.org/lunar-library-overview

https://longnow.org/ideas/a-lunar-library/

Japan plans to preserve 275 human languages on a “memory disk” they will be sending to the Moon:

https://ispace-inc.com/news-en/?p=5311

https://www.space.com/moon-lander-ispace-hakuto-r-memory-disk-human-languages-unesco

https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/private-moon-lander-will-carry-memory-disk-of-275-languages-this-year-5627008

This is similar to what the Long Now Foundation did with the Rosetta Project, which has preserved one thousand human languages on Comet 67P:

https://rosettaproject.org/?ref=longnow.org

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8G6b6EbAWo&t=291s

My hope is that future efforts to preserve humanity in deep space are more detailed and informative than what was placed on the New Horizons probe that flew past Pluto in 2015:

http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html

All that mission team had to do, if they could not have been bothered otherwise, was to reproduce the Pioneer Plaque, for even the basic probe diagram on that interstellar message resembled the NH probe.

https://www.planetary.org/articles/0120-the-pioneer-plaque-science-as-a-universal-language

Otherwise, except for the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the artifacts on that vessel feel very much like the efforts one makes for a small-town time capsule. I guess perhaps they will deliver their own message about humanity in that time and place to whoever finds it one day.

Archaeologists are always finding random bits of artifacts and they mean something to them…and create a story about us. Radom flints, charcoal, and even bodies of the long-dead mean things to specialists that contribute to our understanding of our past. The extraction of DNA tells us more about our origins and relationships with extant hominids tens of thousands of years ago.

Museums are full of human artifacts that shed light on our past, and new discoveries reveal it in ever more detail, yet it is still largely unknown. Historical records are partly revealing, but lack the details of life and events, which are partially filled with the evidence of artifacts.

One of my small interests in watching old movies is seeing how people lived during the last century. However, one detail is almost invariably missing – what were toilets like, and even recreations of past periods never reveal how people used chamberpots or cleaned their rear ends (remember high-status women were once sewn into their complex layered dresses) and most people couldn’t give a proverbial sh*t about that.

Most people today do not know about many instruments of the Victorian era, even the cutlery has changed since I was young – where are fish knives and pastry forks in cutlery sets today? How about this Roman artifact with an unknown function? We think we know much about Roman society, yet these ubiquitous objects have never had their function described. In another millennium, the vast number of contemporary artifacts will have unknown functions and likely be inoperable anyway. Won’t historians wish they understood their function and role in our civilization?

The Golden Disk on the Voyager probes are unlikely to ever be seen by human or alien eyes. I would suggest that their modern format should be mass-produced every decade with updated information whose ubiquity would provide a record of our civilization’s lesser-noted social information to provide more texture of our time to our descendants and at a minimum added to every time capsule and building we create.

Alex Tolley said on December 19, 2024 at 11:59:

“The Golden Disk on the Voyager probes are unlikely to ever be seen by human or alien eyes. I would suggest that their modern format should be mass-produced every decade with updated information whose ubiquity would provide a record of our civilization’s lesser-noted social information to provide more texture of our time to our descendants and at a minimum added to every time capsule and building we create.”

Something like this is going on with Golden Record 2.0:

https://research.avenues.org/goldenrecord/

https://www.geekwire.com/2024/microsoft-silica-golden-record-glass/

https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/golden-record-2-0/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/golden-record-180951490/

https://www.space.com/37922-one-earth-message-new-horizons-golden-record.html

There is also something called the Last Arecibo Message:

https://www.universetoday.com/169845/the-last-arecibo-message-celebrates-the-observatory-and-one-of-its-greatest-accomplishments/

The paper here:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.09790

Unlike its predecessor from 1974, this revised message is still sitting on Earth, awaiting a more daring humanity to launch it into the galaxy.

We should categorically reject all efforts to “protect sites from human activities” on these grounds. I have not read beyond what is said here or in the press release, but this is a case in which the medium truly is the message, in a very specific and meaningful way: the paper is paywalled. In other words, the property rights of Nature Publishing Group are taken as superior to my ability to inquire or debate, or your ability to disseminate knowledge by mirroring a copy of the article here. Now we need only look up to the Moon – our Moon – and mirror that message.

Private industry and nations have been looking for ways to claim, own, and trade in astronomical bodies for decades now, to which the Outer Space Treaty is a clear impediment. We should think of the general public like an elderly relative, vulnerable to scams by phone and internet, each of which has the right to an 8.2-billionth of the lunar landscape, or about 1.14 acres, and we naturally expect someone will relieve them of this burden in due course.

“Protecting” the artifacts almost certainly involves making use of the territory near them off limits, and very likely leads to the suggestion that some particular authority has the right to maintain that territory. A current suggestion, prone to revision, has been at least a two-kilometer radius to avoid damaging infrastructure with dust. Offering similar protection to every discarded heat shield and fractured propeller blade, together with strategic planting of such items, would rapidly place the entire lunar surface under archaeological protection, under control of maintaining authorities.

If we fall for this idea, when all is done, we can look up to the Moon with the relief that the astronauts’ tracks are safe unless NASA or a succeeding owner decides to redevelop them, but it will no longer be our Moon. Rather, it will be a gloating beacon symbolizing the power of whoever buys up all these claims, which the public would originally have given up without receiving a penny. Therefore, I suggest we heed the article’s true message, and hold our own personal collective property rights to the Moon superior to any and all archaeological information that might be obtained from it.

Here’s a question… we spot an impactor headed to the Apollo 11 site. Do we divert it??

At the Smithsonian | July 19, 2024

Apollo Astronauts Left American Flags, Boots and Even Poop on the Moon. Here’s Why These Artifacts Matter

Fifty-five years after the first human lunar landing, scholars and experts are looking to preserve the past as more nations and companies undertake moon missions.

Full article here:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/apollo-astronauts-left-american-flags-boots-and-even-poop-on-the-moon-heres-why-these-artifacts-matter-180984736/

From the above article, here is “the final catalogue” of items placed by humanity on the Moon through July of 2012:

https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/final-catalogue-of-manmade-material-on-the-moon.pdf

The much more detailed Lunar Registry from For All Moonkind:

https://moonregistry.forallmoonkind.org/

One of the longest operating satellites in Earth orbit that just celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in space is Oscar 7…

https://www.theregister.com/2024/11/25/amsat_oscar_7_anniversary/

AMSAT-OSCAR-7: A Still Operational, Small-Satellite History Lesson…

https://www.amsat.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AO-7-History-Lesson-Complete_241015.pdf

And the really interesting part is that Oscar 7 came back to life twenty-one years after being shut off in 1981.

Then there is the tale of the “zombie” satellite Lincoln Experimental Satellite 1 (LES 1) launched in 1965…

https://www.drewexmachina.com/2022/02/11/zombie-satellites-the-tale-of-lincoln-experimental-satellite-1/

This post is one of those that should appear as a letter to the editor or an op-ed in the NY Times or Washington Post. It homes in on a topic that almost no one has ever given a thought to. Let me just put the admission right out there that I am one of those people.

The anthropological slant to the argument is really incisive, but I bet that the economic and tourist slant will get people’s attention more. I’m sad to say it, but I think most people don’t give a hoot about preservation for the sake of historians – not today and surely far less so about some hypothetical historian in a future, whether it’s an imaginable horizon or something incomprehensibly distant and/or alien. It would be ideal to “preserve the stratigraphy” for them, but my mind quickly goes to the way that developers undertake to circumvent the few regulations that say “stop the bulldozer when you see bones”… and the Sotheby’s auctions of artifacts either “lacking a provenience” or “from a private collection”. It’s preservation weighed against money, and my jaded bet is on the money.

There is hope in the fact that the discussion is happening, but words are simply words. Even when the words are codified into written policy with signatories they are, as you point out, routinely non-binding, and if enacted into actual law… well, people don’t pay attention to silly things like that. Witness the way that R&D continues (although not spoken of until caught out) into human cloning and weaponized AI and who knows what other areas where angels fear to tread. Protect the Clovis points and Ranger 7 crash site? We don’t even protect the conditions that make life possible on our planet, because there’s money to be made in destroying those conditions. People collect arrowheads and will gladly add to the “spirited bidding” on the auction floor and identity-protecting phone lines and web platforms for pieces of an Apollo lander. If there is anything still there on the Moon it will be covered in graffiti and “Kilroy was here”. Who or what will stop it, despite whatever law may exist? How could any such law be enforced? Park rangers stationed at each and every site of interest on the Lunar surface? Mars police? I fear that the catalogue you mention of sites to preserve would serve mostly as a locater map for those who would pillage them. Such is the vision of Human nature in my cynical eyes.

As for acting now to get policies in place, again my pessimism prevails. Humans do not divert attention or resources away from current issues to something that is not yet a crisis. We can think about investing in fire extinguishers only when the flames are actually hot enough to feel. That’s when governing bodies begin to consider allocating resources to fire extinguishers. And when journalists break the story that the off-planet sites have been stripped and materials are showing up on Ebay the legislative enquiry committee will simply say that the minority party dropped the ball and should have done something sooner. The journalists will mention the warnings voiced by Steven Howe, Justin Holcomb, and Paul Gilster decades earlier… and that will be that… another episode of Humans missing the opportunity… another example of Human behavior.

I actually am sorry that I see things in such a negative light but looking around at the track record of history and the news alerts on my phone, I am overwhelmed by unencouraging evidence. What should be is one thing and what probably will be is another. I’m a hopeless gloomy Gus.

But I loved the post. Really. Needs to be said, and took me into some thinking that had not occurred to me. Thanks for doing that.

The whole world can’t be a museum. These missions are already well documented, there are quite a few of them, and some of the artifacts will doubtless survive by chance or in the hands of private collectors who meticulously document their eBay finds to preserve the market value. When people on Earth have the notion that every broken wheel and helicopter blade is “heritage”, usually they are deemed “hoarders” and government officials and therapists seem to crawl out of the woodwork to helpfully throw away their possessions at random. Here I feel like we will be urged to build a museum around the Apollo lander site to protect it, and in fifty years when it becomes dated, we can build a museum around that to document the technology of a 2030s-era space museum, and so on.

But I don’t believe it, and I don’t believe the people proposing it believe it. The Apollo lander site may be historical, but above all it is a flag staked on a new land to lay claim to it. We should use our interest in history to look backward to other cases where the altruistic impetus to scientific inquiry has been taken advantage of, quite easily, for territorial assignations that ended most evilly.

Specifically, I would very much encourage people to learn the history of the International Association of the Congo. This was a high-minded international organization founded 1879 to explore the interior of Africa … which turned out to be a sordid process by which the infamous Leopold II of Belgium took control of the Congo, running it as an anarcho-capitalist corporate utopia, inflicting the greatest atrocities upon its inhabitants. To this day, people remember the fluffy propaganda: “Doctor Livingstone, I presume”, The Lost World. They think Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” was a poetic work of literary fiction and analyze its writing style. What they don’t understand is that the HIV that still ravages the health of so many people originated near Kinshasa before the first World War. They can’t picture that the inhabitants, forced to scour the jungle for the last few rubber vines or present the chopped-off hands of other luckless inhabitants as substitute payment, were using those same machetes to kill monkeys and any other bush meat they ran across to assuage their hunger. They still think some Africans must have had sex with green monkeys!

So no, I don’t think we should take the protection of these artifacts very seriously. There is a market for them, and private or public recovery missions could bring some of them to museums people could actually visit. But when someone asks us to sign over the Moon to their care, we should refuse with unrepentant rudeness.

https://www.newsweek.com/nasa-apollo-11-moon-rock-destroyed-fire-ireland-2007370

NASA Apollo 11 Moon Rock Was Destroyed in a Fire, Records Reveal

Published December 30, 2024 at 7:42 AM EST

By Tom Howarth

Science Reporter (Nature)

A piece of moon rock gifted to Ireland following NASA’s historic Apollo 11 mission in 1969 was tragically destroyed in a fire, newly uncovered documents from Ireland’s National Archives reveal.

The rock, which had traveled almost 240,000 miles from the moon to Earth, was presented to then-President Éamon de Valera in 1970 by U.S. Ambassador J.G. Moore.

However, a lack of clarity over where it should be displayed led to years of mishandling, confidential 1984 memos seen by PA news agency showed.

Initially stored in a government basement for over three years, the artefact was eventually entrusted to the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in 1973. It was placed at Dunsink Observatory for public display but was lost in a fire there on October 3, 1977.

Thankfully, Ireland had received a second piece of lunar material in 1973, also gifted by the U.S. This sample from Apollo 17, mounted on a plaque featuring the Irish tricolor, found a more stable, albeit temporary, home.

[Yes, but what might have that first lunar sample from Apollo 11 contained which science could have learned from it, especially in later years? And historically, there are only so many samples of the Moon from the first human lunar landing.]

Initially displayed at the President’s official residence, Áras an Uachtaráin, the rock was later loaned to Aer Lingus for the 1976 Young Scientist Exhibition. Over the years, it was moved between various locations, including Dublin Airport, as officials struggled to find a permanent display space.

The sample is now held by the National Museum of Ireland.

https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2024/09/human-genome-stored-on-everlasting-memory-crystal-.page

Human genome stored on ‘everlasting’ memory crystal

Published:19 September 2024

University of Southampton scientists have stored the full human genome on a 5D memory crystal – a revolutionary data storage format that can survive for billions of years.

The team hope that the crystal could provide a blueprint to bring humanity back from extinction thousands, millions or even billions of years into the future, should science allow.

The technology could also be used to create an enduring record of the genomes of endangered plant and animal species faced with extinction.

Eternity crystals

The 5D memory crystal was developed by the University of Southampton’s Optoelectronics Research Centre (ORC).

Unlike other data storage formats that degrade over time, 5D memory crystals can store up to 360 terabytes of information (in the largest size) without loss for billions of years, even at high temperatures. It holds the Guinness World Record (awarded in 2014) for the most durable data storage material.

The crystal is equivalent to fused quartz, one of the most chemically and thermally durable materials on Earth. It can withstand the high and low extremes of freezing, fire and temperatures of up to 1000 °C. The crystal can also withstand direct impact force of up to 10 ton per cm2 and is unchanged by long exposure to cosmic radiation.

The team at Southampton, led by Professor Peter Kazansky , use ultra-fast lasers to precisely inscribe data into nanostructured voids orientated within silica – with feature sizes as small as 20 nanometres.

Unlike marking only on the surface of a 2D piece of paper or magnetic tape, this method of encoding uses two optical dimensions and three spatial co-ordinates to write throughout the material – hence the ‘5D’ in its name.

Restoring species

The longevity of the crystals mean they will outlast humans and other species. Currently it’s not possible to synthetically create humans, plants and animals using genetic information alone, but there have been major advances in synthetic biology in recent years, notably the creation of a synthetic bacterium by Dr Craig Venter’s team in 2010.

Memory of Mankind archive in Hallstatt, Austria

“We know from the work of others that genetic material of simple organisms can be synthesised and used in an existing cell to create a viable living specimen in a lab,” says Prof Kazansky.

“The 5D memory crystal opens up possibilities for other researchers to build an everlasting repository of genomic information from which complex organisms like plants and animals might be restored should science in the future allow.”

To test this concept, the team created a 5D memory crystal creating containing the full human genome. For the approximately three billion letters in the genome, each letter was sequenced 150 times to make sure it was in that position. The deep-read sequencing work was done in partnership with Helixwork Technologies .

Visual clues

The crystal is stored in the Memory of Mankind archive – a special time capsule within a salt cave in Hallstatt, Austria.

When designing the crystal, the team considered if the data held within it might be retrieved by an intelligence (species or machine) which comes after us in the distant future. Indeed, it might be found so far into the future that no frame of reference exists.

“The visual key inscribed on the crystal gives the finder knowledge of what data is stored inside and how it could be used,” says Prof Kazansky.

Above the dense planes of data held within, the key shows the universal elements (hydrogen, oxygen, carbon and nitrogen); the four bases of the DNA molecule (adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine) with their molecular structure; their placement in the double helix structure of DNA; and how genes position into a chromosome, which can then be inserted into a cell.

For a visual indication of which species the 5D memory crystal relates to, the team paid homage to the Pioneer space craft plaques which were launched by NASA on a path to take it beyond the confines of the Solar System.

“We don’t know if memory crystal technology will ever follow these plaques in distance travelled but each disc can be expected with a high degree of confidence to exceed their survival time,” adds Prof Kazansky.

https://astrobiology.com/2024/12/percolation-of-civilisation-in-a-homogeneous-isotropic-universe-2.html

Percolation Of ‘Civilisation’ In A Homogeneous Isotropic Universe

By Keith Cowing

Status Report

astro-ph.CO

December 29, 2024

In this work, we consider the spread of a ‘civilisation’ in an idealised homogeneous isotropic universe where all the planets of interest are habitable.

Following a framework that goes beyond the usual idea of percolation, we investigate the behaviour of the number of colonised planets with time, and the total colonisation time for three types of universes. These include static, dark energy-dominated, and matter-dominated universes.

For all these types of universes, we find a remarkable fit with the Logistic Growth Function for the number of colonised planets with time. This is in spite of the fact that for the matter- and dark-energy dominated universes, the space itself is expanding.

For the total colonisation time, T, the case for a dark energy-dominated universe is marked with divergence beyond the linear regime characterised by small values of the Hubble parameter, H. Not all planets in a spherical section of this universe can be ‘colonised’ due to the presence of a shrinking Hubble sphere.

In other words, the recession speeds of other planets go beyond the speed of light making them impossible to reach. On the other hand, for a matter-dominated universe, while there is an apparent horizon, the Hubble sphere is growing instead of shrinking. This leads to a finite total colonisation time that depends on the Hubble parameter characterising the universe; in particular, we find T∼H for small H and T∼H2 for large H.

Allan L. Alinea, Cedrix Jake C. Jadrin

Comments: 10 pages, 8 figures

Subjects: Popular Physics (physics.pop-ph); Cosmology and Nongalactic Astrophysics (astro-ph.CO)

Cite as: arXiv:2309.06575 [physics.pop-ph] (or arXiv:2309.06575v1 [physics.pop-ph] for this version)

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.06575

Focus to learn more

Journal reference: Eur. J. Phys. 44 6 (2023) 065601

Related DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6404/acfbc5

Focus to learn more

Submission history

From: Allan Alinea

[v1] Sun, 27 Aug 2023 12:13:54 UTC (262 KB)

https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.06575

Astrobiology, SETI

We need protective regulations on our space artifact history, or we will end up with more problems like this. ..

https://legaltalktexas.hammerle.com/probate/astronauts-and-their-artifacts-how-a-little-hammer-from-the-apollo-12-mission-made-texas-law/

https://nasawatch.com/exploration/personal-things-on-board-odysseus-resting-on-the-moon/

Personal Things On Board Odysseus – Resting On The Moon

By Keith Cowing

NASA Watch

March 11, 2024

Keith’s note: A few weeks ago a robotic explorer named Odysseus completed a journey – one not unlike its mythological human namesake undertook – and struggled ashore at the south pole of the Moon. While injured and out of sorts for a while, Odysseus managed to accomplish much of what it had been tasked to do – starting with a precision landing in a place no human or droid has ever visited before. The way that Odysseus made it to the lunar surface involved some truly heroic thinking the mission control team – rather fitting for a space droid named after a hero.

Odysseus – aka IM-1 – was sent to the Moon by Intuitive Machines as a commercial mission with NASA being one – albeit the largest – customer with various scientific payloads on board. Among the commercial partners was Lonestar Data Holdings which had the first fully operational lunar data center onboard.

In addition to the NASA science payloads there were also many other things on board ranging from personal mementos to works of art to things of historic importance which were stored inside Lonestar’s data center on Odysseus.

According to Lonestar CEO Chris Stott: “Our primary payload was from the State of Florida which comprised the overwhelming amount of data i.e. 99% on board. This was a visionary forward-looking step by the State of Florida regarding the protection of its crucial data for its citizens and government. For this mission they chose the maps and data covering every state park in Florida. In essence this was Florida on the Moon – launched from Florida – taken there by a Floridian company. We then also formally carried data for the SSPI the largest networking and educational scholarship organization in the global space industry.” (BTW Chris Stott is Chair Emeritus alongside Sir Arthur C. Clarke.)”

Stott continued: “We carried images and art from a number of NGOs and non-profits: images of the Explorers Club flag, the Challenger Center logo, Conrad Foundation logo, and the Space For Art Foundation, founded by astronaut Nicole Stott whose incredible art therapy work with pediatric cancer patients and refugee children around the work is deeply inspiring to the entire Lonestar team – and many others around the world. In a purely personal and informal gesture, we then also privately carried a series of images and photos for the Lonestar team, investors, advisors, friends, and family – including an image from Sian Proctor from her flight, and of course your image, Keith.”

Rather than try to weave everything into a larger story I am going to list the things that I know about one by one contained within the memory of IM-1. My item is the last on the list. As such you would be quite right in assuming I have a biased take on this mission and all that was on board.

A copy of the formal position paper “Private Sector Utilization of the Moon: A Right of Use“ written by Delbert Smith and Chris Stott for the American Bar Association (ABA);

A copy of the sheet music for The Moons Symphony – 7 Movements for Orchestra and Choir composed by Amanda Lee Flakenberg;

A copy of “Light of the Moon” by Davy Knowles (a native of the Isle of Man);

Artwork by astronaut Sian Proctor;

Some data for the AMAR Foundation for Baroness Nicholson;

And as part of the data center test the U.S. Declaration of Independence was sent to the Moon and the back to Earth.

In addition The Earthling Project crowdsourced voices from around the world representing humanity’s spirit and diversity – and they are onboard Odysseus as well – see “Odysseus Has a New Home and Brings the Earthling Project Along for the Ride” from the SETI Institute. The Earthling Project is part of a collaboration between Pérez Santiago and Dr. Jill Tarter, co-founder of the SETI Institute and an astronomer best known for her pioneering work in SETI research.

https://www.seti.org/press-release/odysseus-has-new-home-and-brings-earthling-project-along-ride

If I come across any other things that were on board I’ll be certain to add them.

Chris Stott added some historic context to how his team at Lonestar gets through the day “The quote we keep up on the big screen every day all day for all our work – “For the ashes of our fathers and the temples of our gods” – from Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay. Yes, we changed it a little … but the sentiment is very much the same.”

“Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods.”

The barbarians are literally at our gates … what will we do …?”

We are resuming a vigorous program of robotic and human exploration of the moon – a natural continuation of what we have done on Earth. Chris Stott makes reference to “Horatius” – Horatius Cocles – a famous Roman general – on a spacecraft landing on the Moon named after Odysseus a legendary Greek king of Ithaca mentioned in Homer’s “Odyssey” and the “Iliad”. You space exploration history types may recall that Craig Steidle used a famous line “Fortuna Audaces Juvat” i.e. “Fortune favors the bold” a latin proverb most prominently repeated in Virgil’s “Aeneid” at 10.284. Jim Bridenstine often ended many official statements with “Ad Astra” (“to the stars”) which is taken from another Latin phrase common in exploration and military history “Per aspera ad astra / ad astra per aspera“ (“through hardships to the stars”). Bridenstine often used the phrase “Forward to the Moon” as his variant to this notion. And of course the NASA program to return humans to the Moon is named “Artemis” after the sister of Apollo.

Alas, NASA no longer bothers to do much in the way of noting historic resonances (see “Spaceship Endeavour Is In Orbit“). The exploration of space is a natural extension of humanity’s exploration of our home world. This was something that astronaut John Grunsfeld and I tried to capture in the NASA Administrator’s Symposium that we developed and co-chaired “Risk and Exploration: Earth, Sea and the Stars” in 2004. I would hope that NASA goes beyond just “Apollo 2.0” sorts of things and really embraces all aspects of human exploration as they head back to the Moon.

Oh yes. Then there’s my picture on board Odysseus:

Background: Chris Stott and I both served on the board of Directors of the Challenger Center. His wife Nicole helped to start the whole “Flat Gorby” thing which ended up with a picture of Astronaut Sun Williams’ dog Gorby and me on the summit of Mt. Everest with another Astronaut Scott Parazynski along with some Moon rocks. Scott and I had some Apollo 11 Moon rocks with us in Nepal which are now on the ISS along with a piece of the summit of Mt. Everest. We also sent prayer flags honoring lost astronauts and various non-profit organizations with Scott to leave on the summit. These memorials that Scott and I did inspired student Michael Kronmiller (whose parents are long time space community members) who was doing education programs with students in Nepal to get a piece of Everest (i.e. another piece of Nepal) to place on the Peregrine Lander which was supposed to go to the Moon. But it didn’t. So stay tuned – we may try this again.

For those who may still question the importance of properly preserving humanity’s culture for future generations, regardless of the subject…

https://www.npr.org/2025/01/09/nx-s1-5252939/getty-villa-museum-threatened-by-wildfire-but-collection-remains-safe

and…

https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/california-fires-destroy-priceless-theosophical-archive

To quote:

I was just told that the entire property of the Theosophical Society in Altadena near Pasadena has been completely destroyed by the fires in Los Angeles. This was the world’s largest archive of Theosophical materials, including a library with 40.000 titles, the entire archive of the history of the TS, including ca. 10.000 unpublished letters, pertaining to HPB, the Mahatmas, W.Q. Judge, G.R.S. Mead, Katherine Tingley, and G. de Purucker, membership records since 1875, art objects, and countless other irreplaceable materials. The archives also contained works of Boehme, Gichtel, donations from the king of Siam including rare Buddhist scriptures, and so on.

Remember the fire that destroyed Brazil’s National Museum in 2018:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/artifacts-destroyed-brazil-devastating-national-museum-fire-180970194/

Why Brazil’s National Museum Fire Was a Devastating Blow to South America’s Cultural Heritage

The collection of more than 20 million artifacts included the oldest fossil found in the Americas and a trove of indigenous literature

My essay on the subject of preserving humanity in deep space:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2013/01/18/the-last-pictures-contemporary-pessimism-and-hope-for-the-future/

The American flags planted on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts were not meant to last…

https://www.space.com/what-happened-to-the-american-flags-on-the-moon?

On the other hand, China has different plans for their flags…

https://www.space.com/the-universe/moon/china-plans-to-plant-a-waving-flag-on-the-moon-in-2026-heres-how

And…

https://www.space.com/china-change-6-moon-flag-basalt

Six Flags on the Moon: What is Their Current Condition?

https://www.nasa.gov/history/alsj/ApolloFlags-Condition.html

The Chinese flag on the lunar farside is designed to last at least ten thousand years – and probably much longer than that:

https://www.induqin.com/post/chinese-flag-on-chang-e-6-engineered-for-a-10-000-year-legacy

To quote:

In Chinese, basalt rock is called Xuanwu rock, named after a mythical creature symbolizing the north and winter. “We crushed and melted the rocks to draw them into thin threads, each about one-third the diameter of a human hair,” explained Professor Zhou Changyi from the National Space Science Centre at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to China Global Television Network (CGTN).

Zhou added that the flag, made from basalt fibres, could last over 10,000 years on the moon due to its resistance to corrosion, heat, and cold. He also mentioned that this material could be used to construct China’s future lunar research base, as this type of rock is abundant on the moon. It reportedly took researchers over a year to develop the method for producing basalt fibres.

Another small step for mankind…

ICOMOS and WMF Recognize the Moon on the 2025 World Monuments Watch

aerospace heritage

– Created: 14 January 2025

The World Monuments Fund has announced its 2025 Watch: 25 sites are listed this year in the biennial nomination-based advocacy programme, including… the Moon!

The nomination of the satellite originated from ICOMOS’ International Scientific Committee on Aerospace Heritage, which was launched in 2023.

As a new era of space exploration dawns, international collaboration is required to protect the physical artifacts of early Moon landings.

One giant leap for mankind

With the dawn of the Space Age, the physical remnants of early Moon landings are under threat, jeopardizing these enduring symbols of collective human achievement.

The landing site, known as Tranquility Base, preserves some 106 assorted artifacts related to the event, including the landing module, scientific instruments, biological artifacts, and commemorative objects, as well as Neil Armstrong’s iconic boot print.

Tranquility Base is one of over 90 historic landing and impact sites that mark humankind’s presence on the Moon’s surface and testify to some of our most extraordinary feats of courage and ingenuity.

They represent remarkable science and engineering milestones rooted in millennia of astronomical study and remain a source of growing scientific knowledge. These landing sites also mark moments that stirred the collective imagination and inspired a sense of global wonder and shared accomplishment.

[…] We have carried our artifacts and created sites on the Moon in what is only the blink of an eye in the archaeological record. All cultures through early time have narratives, traditional practices and relationships to the night sky and the Moon, in particular. The WMF seeks, as our Scientific Committee does, to view the Moon as belonging to humanity and to advocate for the preservation of significant places within an international framework, inspired by previous preservation efforts done through the Antarctic Treaty and 1954 Hague Convention as well as other global treaties and agreements. […]

Professor Beth O’Leary, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Aerospace Heritage

Full article here:

https://www.icomos.org/en/89-english-categories/home/153492-icomos-and-wmf-recognize-the-moon-in-2025-world-monuments-watch

And…

Out of this world: the Moon features on World Monuments Fund’s list of threatened sites

Allison C. Meier

15 January 2025

For the first time, the list of threatened heritage sites raises awareness beyond Earth’s atmosphere

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/01/15/out-of-this-world-the-moon-features-on-world-monuments-funds-2025-watch-list

To quote:

The most surprising inclusion on the list may be the Moon. While its nomination concentrated on the Apollo 11 landing site, where the bootprints of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin remain in the lunar dust alongside objects of their scientific work, WMF is considering the wider framework needed to protect historic sites connected with space exploration. A future rise of commercial lunar landings could see the potential for looting, exploitation or the loss of these sites.

“As we enter a new era of space exploration, establishing international mechanisms to protect this cultural landscape is crucial,” Montlaur says. “Safeguarding lunar heritage will prevent damage from accelerating private and governmental activities in space, ensuring these artefacts endure for future generations.”

…

“Importantly, listing a site on the Watch is just the beginning,” Montlaur says. “WMF works closely with partners to design projects addressing the identified challenges and secures funding to support them. For the 2025 Watch cycle, we have already raised $2m to allocate to Watch projects and will continue fundraising to meet the needs of our nominated sites.”

https://www.gmu.edu/news/2025-01/george-mason-scientist-anamaria-berea-leads-team-design-lunar-cultural-archive

George Mason scientist Anamaria Berea leads team to design lunar cultural archive for the ‘Pioneers of Tomorrow’

January 16, 2025 / By Tracy Mason

The ASPIRE ONE Lunar Record launched early on January 15 as part of the Ghost Riders in the Sky Lunar mission from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, with a goal of establishing a new theoretical framework for planetary-scale archival communication.

Anamaria Berea, an associate professor of computational sciences at George Mason University, led an interdisciplinary team that designed a part of the LifeShip payload—an archive to preserve our Earth’s cultural and scientific heritage. It will be placed on the Moon through Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Lander.

Firefly missions are part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative in the Artemis program.

The digital portion of the LifeShip payload, similar to the Voyager Golden Records, contains diverse content including videos, global aspirations, scientific materials, historical records, and cultural artifacts intended for future humans to access. Highlights include Daily Life video capturing global snapshots of contemporary life, an Aspirations video featuring individuals sharing hopes for the future in their native languages, and collections of images from UNESCO and World Heritage archives. A Getty images documentation of the recent COVID-19 pandemic is also included.

“We basically created an archive that is housed on a 1GB microchip encoded with diverse content,” said Berea, who also has a PhD is computational social sciences from George Mason. “It is also engraved with NanoFiche, including Berea’s name and affiliation with George Mason University.

If it lands successfully, the payload will be placed on the Moon after 45 days [early March] and live there for posterity.

“This portion of the payload includes the Apollo 11 launch code, various works of art and music, information about the Moon, Earth Constitutions, and more,” Berea shared. “Not only my face, voice, name, and work will be on the Moon for future generations, but George Mason University’s legacy too.”

https://fireflyspace.com/missions/blue-ghost-mission-1/

The LifeShip payload:

https://lifeship.com/blogs/lifeship-mission-control/launch-scheduled-for-january-2025-lifeship-s-pyramid-on-the-moon

A Monument to Life from Earth

The LifeShip Pyramid on the Moon is a monument, seed bank, cultural archive, time capsule, and messenger probe, carrying Earth’s essence beyond. This historic monument represents a giant leap forward in our mission to preserve and continue life from Earth. It is one small step towards spreading life and consciousness across the cosmos. Its timeless geometric form symbolizes humanity’s resilience and monumental achievements, while its placement on the Moon honors our boundless spirit of exploration and expansion. This is a mission in service to life from Earth.