No one ever said Europa Clipper would be able to detect life beneath the ice, but as we look at the first imagery from the spacecraft’s star-tracking cameras, it’s helpful to keep the scope of the mission in mind. We’re after some critical information here, such as the thickness of the ice shell, the interactions between shell and underlying ocean, the composition of that ocean. All of these should give us a better idea of whether this tiny world really can be a home for life.

Image: This mosaic of a star field was made from three images captured Dec. 4, 2024, by star tracker cameras aboard NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft. The pair of star trackers (formally known as the stellar reference units) captured and transmitted Europa Clipper’s first imagery of space. The picture, composed of three shots, shows tiny pinpricks of light from stars 150 to 300 light-years away. The starfield represents only about 0.1% of the full sky around the spacecraft, but by mapping the stars in just that small slice of sky, the orbiter is able to determine where it is pointed and orient itself correctly. The starfield includes the four brightest stars – Gienah, Algorab, Kraz, and Alchiba – of the constellation Corvus, which is Latin for “crow,” a bird in Greek mythology that was associated with Apollo. Besides being interesting to stargazers, the photos signal the successful checkout of the star trackers. The spacecraft checkout phase has been going on since Europa Clipper launched on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket on Oct. 14, 2024. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Seen in one light, this field of stars is utterly unexceptional. Fold in the understanding that the data are being sent from a spacecraft enroute to Jupiter, and it takes on its own aura. Naturally the images that we’ll be getting at the turn of the decade will far outdo these, but as with New Horizons, early glimpses along the route are a way of taking the mission’s pulse. It’s a long hike out to our biggest gas giant.

I bring this up, though, in relation to new work on Enceladus, that other extremely interesting ice world. You would think Enceladus would pose a much easier problem when it comes to examining an internal ocean. After all, the tiny moon regularly spews material from its ocean out through those helpful cracks around its south pole, the kind of activity that an orbiter or a flyby spacecraft can readily sample, as did Cassini.

Contrast that with Europa, which appears to throw the occasional plume as well, though to my knowledge, these plumes are rare, with evidence for them emerging in Hubble data no later than 2016. It’s possible that Europa Clipper will find more, or that reanalysis of Galileo data may point to older activity. But there’s no question that in terms of easy access to ocean material, Enceladus offers the fastest track.

Enceladus flybys by the Cassini orbiter revealed ice particles, salts, molecular hydrogen and organic compounds. But according to a new paper from Flynn Ames (University of Reading) and colleagues, such snared material isn’t likely to reveal life no matter how many times we sample it. Writing in Communications Earth and Environment, the authors make the case that the ocean inside Enceladus is layered in such a way that microbes or other organic materials would likely break down as they rose to the surface.

In other words, Enceladus might have a robust ecosystem on the seafloor and yet produce jets of material which cannot possibly yield an answer. Says Ames:

“Imagine trying to detect life at the depths of Earth’s oceans by only sampling water from the surface. That’s the challenge we face with Enceladus, except we’re also dealing with an ocean whose physics we do not fully understand. We’ve found that Enceladus’ ocean should behave like oil and water in a jar, with layers that resist vertical mixing. These natural barriers could trap particles and chemical traces of life in the depths below for hundreds to hundreds of thousands of years.”

The study relies on theoretical models that are run through global ocean numerical simulations, plugging in a timescale for transporting material to the surface across a range of salinity and mixing (mostly by tidal effects). Remarkably, there is no choice of variables that offers an ocean that is not stratified from top to bottom. In this environment, given the transport mechanisms at work, hydrothermal materials would take centuries to reach the plumes, with obvious consequences for their survival.

From the paper:

Stable stratification inhibits convection—an efficient mechanism for vertical transport of particulates and dissolved substances. In Earth’s predominantly stably stratified ocean this permits the marine snow phenomena, where organic matter, unable to maintain neutral buoyancy, undergoes ’detrainment’, settling down to the ocean bottom. Meanwhile, the slow ascent of hydrothermally derived, dissolved substances provides time for scavenging processes and usage by life, resulting in surface concentrations far lower than those present nearer source regions at depth.

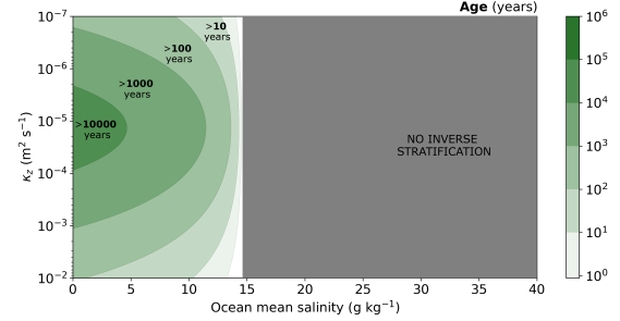

Although its focus is on Enceladus, the paper offers clear implications for what may be going on at Europa. Have a look at the image below (drawn not from the body of the paper but from the supplementary materials linked after the footnotes) and you’ll see the problem. We’re looking at these findings as applied to what we know of Europa.

Image: From part of Figure S7 in the supplementary materials. Caption: “Tracer age (years) at Europa’s ocean-ice interface, computed using the theoretical model outlined in the main text. Note that age contours are logarithmic.” Credit: Ames et al.

The figure shows the depth of the inversion and age of the ice shell for the same ranges in ocean salinity as inserted for Enceladus. Here we have to be careful about how much we don’t know. The ice thickness, for instance, is assumed as 10 kilometers in these calculations. Given all the factors involved, the transport timescale through the stratified layers of the modeled Europa is, as the figure shows, over 10,000 years. The same stratification layers impede delivery of oxidants from the surface to the ocean.

So there we are. The Ames paper stands as a challenge to the idea that we will be able to find evidence of life in the waters just below the ice, and likewise indicates that even if we do begin to trace more plumes from Europa’s ocean, these would be unlikely to contain any conclusive evidence about biology. Just what we needed – the erasure of evidence due to the length of the journey from the ocean depths to the ice sheet. Icy moons, it seems, are going to remain mysterious even longer than we thought.

The paper is Ames et al., “Ocean stratification impedes particulate transport to the plumes of Enceladus,” Communications Earth & Environment 6 (6 February 2025), 63 (full text).

Most of the paper assumes a fairly static subsurface ocean. The authors did try a general circulation model for lateral fluid flow but ruled it not important for their model – that is that the Earth’s global ocean circulation due to salinity and temperature is not well replicated on Enceladus. The authors did not examine Coriolis-induced currents explicitly, but given Enceladus’ rotation (tidally locked to Saturn) of 1.37 Earth days, it seems to me that such current circulations could exist in that ocean. Now whether those currents induce mixing between layers, idk.

What does seem apparent is that any assumed movement of surface peroxides into the ocean would stall just beneath the surface ice crust, ensuring an anoxic ocean depth, and therefore ensuring any life would be anaerobic.

But my main issue with the paper which purports that detecting life’s organic molecules would be largely, if not completely, unable to breech the surface due to the static layers. This might be true of sessile microbes, but motile life could penetrate the layers, just as they do on Earth. What would prevent motile organisms traversing the layers for some purpose, such as feeding, acquiring oxygen, or even breeding to establish populations just under the ice? These organisms would then be ejected with the plumes.

Now I don’t think the subsurface oceans of icy moons are inhabited, but if they are, I would not rule out, in the immortal words of fictional chaotician Ian Malcolm, “life finds a way.”

Interesting. Thanks for posting this. Clipper may be able to illuminate the situation of oceanic stratification on Europa. I’m not sure if the instruments have the fidelity to resolve the salinity gradient sufficiently to infer the presence or lack of such an inversion layer. Magnetometric depth resolution is limited. Maybe RIME finding brine pockets in the ice might be a hopeful sign?

This has broader astrobiological implications beyond our stellar system. Ocean worlds will vastly outnumber earth analogs. I’m not thinking of superearth tier ocean worlds which have much greater problems, but smaller ones sans high pressure ices. The stratification question is a topic needing more attention.

I wonder whether the paper accounted for, e.g. areas of lower and higher concentration of radioactive (hotter) material. That could generate plumes which might penetrate the stratification.

https://astrobiology.com/2024/11/ocean-weather-systems-on-icy-moons-with-application-to-enceladus.html

Ocean Weather Systems On Icy Moons With Application To Enceladus

By Keith Cowing

Status Report

Sci Adv via PubMed

November 18, 2024

We explore ocean circulation on a rotating icy moon driven by temperature gradients imposed at its upper surface due to the suppression of the freezing point of water with pressure, as might be induced by ice thickness variations on Enceladus.

Using high-resolution simulations, we find that eddies dominate the circulation and arise from baroclinic instability, analogous to Earth’s weather systems. Multiple alternating jets, resembling those of Jupiter’s atmosphere, are sustained by these baroclinic eddies.

We establish a theoretical model of the stratification and circulation and present scaling laws for the magnitude of the meridional heat transport.

These are tested against numerical simulations. Through identification of key nondimensional numbers, our simplified model is applied to other icy moons. We conclude that baroclinic instability is central to the general circulation of icy moons.

Ocean weather systems on icy moons, with application to Enceladus, Sci Adv. 2024 Nov 6;10(45):eadn6857. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adn6857 via PubMed (open access)

Astrobiology

Paper online here:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11540039/

It is interesting that this paper appears to come to the opposite conclusion of the OP paper.

That is good for science at least. As you said elsewhere in this thread, we need to get lander missions to these moons.

For example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enceladus_Orbilander

This essay has a nice collection of links to orbiter and lander proposals:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2018/02/09/europa-and-enceladus-hotspots-for-life/

A new lightweight instrument could directly find life on Europa or Mars

The LDMS may be key to unlocking the secrets of the Solar System…

https://www.inverse.com/science/ldms-instrument-europa-mars-enceladus

Laser desorption mass spectrometry with an Orbitrap analyser for in situ astrobiology:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-022-01866-x

https://astrobiology.com/2024/11/distinguishing-potential-organic-biosignatures-on-ocean-worlds-from-abiotic-geochemical-products-using-thermodynamic-calculations-2.html

Distinguishing Potential Organic Biosignatures on Ocean Worlds from Abiotic Geochemical Products using Thermodynamic Calculations

By Keith Cowing

Status Report

chemrxiv.org

November 8, 2024

The search for life in our solar system often involves efforts to detect organic molecules, which have been found on many extraterrestrial bodies, including planets, moons, meteorites, comets, and asteroids. These chemical signatures are not typically thought of as biosignatures because we know that organic synthesis can occur through abiotic processes.

Therefore, development of methods for distinguishing biotic and abiotic biosignatures would enable interpretation of data collected from habitability and life-detection missions. Life on Earth harnesses energy-releasing reactions to power biosynthesis reactions, which often require energy. Using thermodynamic data, we can quantify the energy required for organic synthesis.

If an organic molecule is detected in an abundance that is thermodynamically unstable, then it is possible that life coupled its synthesis to other energy-releasing reactions. On the other hand, if an organic molecule is detected in an abundance that is thermodynamically stable, then abiotic synthesis was plausible.

This sorting framework can be applied to the search for life wherever we have geochemical data. One such example is Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Small compounds involving the elements that comprise the majority of biomass were detected by the Cassini spacecraft in the plume gas erupting from the subsurface ocean.

Using Enceladus as an example, we demonstrate the utility of thermodynamic calculations for distinguishing biosignatures and show that organic synthesis is often favorable using the carbon sources available on Enceladus.

While these results may lead us to conclude that hypothetical organic signatures on Enceladus are abiotic, this framework can be applied to other environments in the search for genuine biosignatures.

Distinguishing Potential Organic Biosignatures on Ocean Worlds from Abiotic Geochemical Products using Thermodynamic Calculations, chemrxiv.org

Astrobiology

Paper online here:

https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/6718180312ff75c3a13a58bf

Just one sufficiently large fragment recognizable as part of an organelle would be enough to settle the matter.

https://astrobiology.com/2024/10/simulated-view-of-thermal-emissions-from-europa.html

Simulated View of Thermal Emissions from Europa

By Keith Cowing

Status Report

NASA

October 21, 2024

This image is a simulation of how NASA’s Europa Clipper will understand which areas of the Jovian moon Europa are warm and active by studying the moon’s thermal emissions.

Larger image here:

https://images.nasa.gov/details/PIA26105

Scientists based this image on a model of data from NASA’s Galileo mission and data from an instrument on NASA’s Cassini mission that studied warm regions of Saturn’s moon Enceladus where jets of water ice and organic chemicals spray out from vents in the icy surface.

Europa Clipper’s Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System, or E-THEMIS, will take both daytime and nighttime observations of Europa. The light pink vertical stripes simulate the warm vents seen on the surface of Enceladus, if they were viewed on Europa in the night.

If Europa has warm spots like Enceladus, E-THEMIS is expected to detect such areas on Europa, even from a distance. Europa Clipper will get as close as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from the moon’s surface, resulting in observations at much higher resolution.

Europa Clipper’s three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon’s icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission’s detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

astrobiology

https://astrobiology.com/2024/07/biosignatures-could-survive-near-the-surfaces-of-enceladus-and-europa.html

Biosignatures Could Survive Near The Surfaces of Enceladus and Europa

By Keith Cowing

Press Release

NASA

July 23, 2024

Europa, a moon of Jupiter, and Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, have evidence of oceans beneath their ice crusts. A NASA experiment suggests that if these oceans support life, signatures of that life in the form of organic molecules (e.g. amino acids, nucleic acids, etc.) could survive just under the surface ice despite the harsh radiation on these worlds. If robotic landers are sent to these moons to look for life signs, they would not have to dig very deep to find amino acids that have survived being altered or destroyed by radiation.

“Based on our experiments, the ‘safe’ sampling depth for amino acids on Europa is almost 8 inches (around 20 centimeters) at high latitudes of the trailing hemisphere (hemisphere opposite to the direction of Europa’s motion around Jupiter) in the area where the surface hasn’t been disturbed much by meteorite impacts,” said Alexander Pavlov of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, lead author of a paper on the research published July 18 in Astrobiology.

“Subsurface sampling is not required for the detection of amino acids on Enceladus – these molecules will survive radiolysis (breakdown by radiation) at any location on the Enceladus surface less than a tenth of an inch (under a few millimeters) from the surface.”

The frigid surfaces of these nearly airless moons are likely uninhabitable due to radiation from both high-speed particles trapped in their host planet’s magnetic fields and powerful events in deep space, such as exploding stars. However, both have oceans under their icy surfaces that are heated by tides from the gravitational pull of the host planet and neighboring moons. These subsurface oceans could harbor life if they have other necessities, such as an energy supply as well as elements and compounds used in biological molecules.

Fountains of ice erupt from the surface of Enceladus. The small moon is mostly in shadow, which makes the geysers illuminated by sunlight stand out. Dramatic plumes, both large and small, spray water ice and vapor from many locations along the famed “tiger stripes” near the south pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

The research team used amino acids in radiolysis experiments as possible representatives of biomolecules on icy moons. Amino acids can be created by life or by non-biological chemistry. However, finding certain kinds of amino acids on Europa or Enceladus would be a potential sign of life because they are used by terrestrial life as a component to build proteins. Proteins are essential to life as they are used to make enzymes which speed up or regulate chemical reactions and to make structures. Amino acids and other compounds from subsurface oceans could be brought to the surface by geyser activity or the slow churning motion of the ice crust.

To evaluate the survival of amino acids on these worlds, the team mixed samples of amino acids with ice chilled to about minus 321 Fahrenheit (-196 Celsius) in sealed, airless vials and bombarded them with gamma-rays, a type of high-energy light, at various doses. Since the oceans might host microscopic life, they also tested the survival of amino acids in dead bacteria in ice. Finally, they tested samples of amino acids in ice mixed with silicate dust to consider the potential mixing of material from meteorites or the interior with surface ice.

This image shows experiment samples loaded in the specially designed dewar which will be filled with liquid nitrogen shortly after and placed under gamma radiation. Notice that the flame-sealed test tubes are wrapped in cotton fabric to keep them together because test tubes become buoyant in liquid nitrogen and start floating around in the dewar, interfering with the proper radiation exposure. Credit: Candace Davison

The experiments provided pivotal data to determine the rates at which amino acids break down, called radiolysis constants. With these, the team used the age of the ice surface and the radiation environment at Europa and Enceladus to calculate the drilling depth and locations where 10 percent of the amino acids would survive radiolytic destruction.

Although experiments to test the survival of amino acids in ice have been done before, this is the first to use lower radiation doses that don’t completely break apart the amino acids, since just altering or degrading them is enough to make it impossible to determine if they are potential signs of life. This is also the first experiment using Europa/Enceladus conditions to evaluate the survival of these compounds in microorganisms and the first to test the survival of amino acids mixed with dust.

The team found that amino acids degraded faster when mixed with dust but slower when coming from microorganisms.

“Slow rates of amino acid destruction in biological samples under Europa and Enceladus-like surface conditions bolster the case for future life-detection measurements by Europa and Enceladus lander missions,” said Pavlov. “Our results indicate that the rates of potential organic biomolecules’ degradation in silica-rich regions on both Europa and Enceladus are higher than in pure ice and, thus, possible future missions to Europa and Enceladus should be cautious in sampling silica-rich locations on both icy moons.”

A potential explanation for why amino acids survived longer in bacteria involves the ways ionizing radiation changes molecules — directly by breaking their chemical bonds or indirectly by creating reactive compounds nearby which then alter or break down the molecule of interest. It’s possible that bacterial cellular material protected amino acids from the reactive compounds produced by the radiation.

The research was supported by NASA under award number 80GSFC21M0002, NASA’s Planetary Science Division Internal Scientist Funding Program through the Fundamental Laboratory Research work package at Goddard, and NASA Astrobiology NfoLD award 80NSSC18K1140.

Radiolytic Effects on Biological and Abiotic Amino Acids in Shallow Subsurface Ices on Europa and Enceladus, Astrobiology (open access)

Astrobiology

Full paper here:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2023.0120

https://astrobiology.com/2024/06/hydrothermal-vents-on-the-seafloors-of-ocean-worlds-could-support-life.html

Hydrothermal Vents On The Seafloors Of Ocean Worlds Could Support Life

By Keith Cowing

Press Release

University of California – Santa Cruz

June 25, 2024

We’ve all seen the surreal footage in nature documentaries showing hydrothermal vents on the frigid ocean floor—bellowing black plumes of super-hot water—and the life forms that cling to them. Now, a new study by UC Santa Cruz researchers suggests that lower-temperature vents, which are common across Earth’s seafloor, may help to create life-supporting conditions on “ocean worlds” in our solar system.

Ocean worlds are planets and moons that have—or had in the past—a liquid ocean, often under an icy shell or within their rocky interior. In Earth’s solar system, several of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons are ocean worlds, and their existence has motivated everything from peer-reviewed academic studies and spacecraft missions with satellites, to popular movies like the 2013 sci-fi thriller, The Europa Report.

Many lines of research suggest that some ocean worlds release enough heat internally to drive hydrothermal circulation under their seafloors. This heat is generated by radioactive decay, as occurs deep in the Earth, with additional heat possibly generated by tides.

Rock-heat-fluid systems were discovered on Earth’s seafloor in the 1970s, when scientists observed discharging fluids that carried heat, particles, and chemicals. Many vent sites were surrounded by novel ecosystems, including specialized bacterial mats, red-and-white tubeworms, and heat-sensing shrimp.

Field system on Earth and basis for simulations used in this study. (a) Field site on ∼3.5 M.y. old seafloor of the Juan de Fuca Plate, located between the Juan de Fuca Ridge (to west) and the Cascadia Subduction Zone (to east). A small discharging outcrop to the north (Baby Bare) and a larger recharging outcrop to the south (Grizzly Bare) are separated laterally by ∼50 km and penetrate through regional sediments (Davis et al., 1992; Fisher, Davis, et al., 2003; Fisher, Stein, et al., 2003; Hutnak et al., 2006; Winslow et al., 2016). (b) Basis for sustaining a hydrothermal siphon. Cool recharge of bottom water results in relatively dense pore fluid, in contrast to conditions at a connected discharge site, where warmer and less dense fluid fill pores. This results in higher pressure at depth below the recharge site, driving flow to the discharge site, where it escapes at the seafloor (modified from Fisher & Wheat, 2010). (c) Geometry of the numerical domain used to simulate outcrop-to-outcrop hydrothermal circulation in an earlier study (Winslow & Fisher, 2015) and modified for use in the present study. Dashed line running South-to-North indicates the location of profiles shown in Figure 3. Please see a more detailed representation of the grid in Supporting Information S1 (Figure S1).

Simulating alien seafloors

In this new study, published today in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the researchers used a complex computer model based on hydrothermal circulation as it occurs on Earth. After changing variables like gravity, heat, rock properties and fluid-circulation depth, they found that hydrothermal vents could be sustained under a wide range of conditions. If these kinds of flows occur on an ocean world, like Jupiter’s moon Europa, they could raise the odds that life exists there as well.

“This study suggests that low temperature (not too hot for life) hydrothermal systems could have been sustained on ocean worlds beyond Earth over timescales comparable to that required for life to take hold on Earth,” said Andrew Fisher, study lead author and a distinguished professor of earth and planetary sciences (EPS) at UC Santa Cruz.

The seawater-circulation system that the team based their computer models on was found on a 3.5 million-year-old seafloor in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, east of the Juan de Fuca Ridge. There, cool bottom water flows in through an extinct volcano (seamount), travels underground for about 30 miles, then flows back out into the ocean through another seamount. “The water gathers heat as it flows and comes out warmer than when it flowed in, and with very different chemistry,” explained Kristin Dickerson, the paper’s second author and a Ph.D. candidate in earth and planetary sciences.

The flow from one seamount to another is driven by buoyancy, because water gets less dense as it warms, and more dense as it cools. Differences in density create differences in fluid pressure in the rock, and the system is sustained by the flows themselves—running as long as enough heat is supplied, and rock properties allow enough fluid circulation. “We call it a hydrothermal siphon,” Fisher said.

Earth’s cooling system

While high-temperature vent systems are driven mainly by sub-seafloor volcanic activity, Fisher explained that a much larger volume of fluid flows in and out of Earth’s seafloor at lower temperatures, driven mainly by “background” cooling of the planet. “The flow of water through low-temperature venting is equivalent, in terms of the amount of water being discharged, to all of the rivers and streams on Earth, and is responsible for about a quarter of Earth’s heat loss,” he said. “The entire volume of the ocean is pumped in and out of the seafloor about every half-million years.”

Many previous studies of hydrothermal circulation on Europa and Enceladus, a small moon orbiting Saturn, have considered higher temperature fluids. Cartoons and other drawings often depict systems on their seafloors that look like black smokers on Earth, according to Donna Blackman, an EPS researcher and third author on the new paper. “Lower-temperature flows are at least as likely to occur, if not more likely,” she said.

The team was particularly excited about one result from the computer simulations featured in the new paper showing that, under very low gravity—like that found on the seafloor of Enceladus—circulation can continue with low to moderate temperatures for millions or billions of years. This could help to explain how small ocean worlds can have long-lived fluid-circulation systems below their seafloors, even though heating is limited: the low efficiency of heat extraction could lead to considerable longevity—essentially, throughout the life of the solar system.

Artistic rendering of hydrothermal vents on the seafloor of the Saturnian moon Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Planetary scientists are looking to observations from satellite missions to help determine what kinds of conditions are present or possible on ocean worlds. The authors of the new paper plan to attend the launch of the Europa Clipper spacecraft later this fall at Cape Canaveral, Fla., along with colleagues collaborating on the Exploring Ocean Worlds project.

The researchers acknowledge the uncertainty of when the seafloors of ocean worlds will be directly observed for the presence of active hydrothermal systems. Their distance from Earth and physical characteristics present major technical challenges for spacecraft missions. “Thus, it is essential to make the most of available data, much of it collected remotely, and leverage understanding from decades of detailed studies of analog Earth systems,” they conclude in the paper.

In addition to the UC Santa Cruz team, the paper included co-authors from the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique de Nantes. The study, “Sustaining Hydrothermal Circulation with Gravity Relevant to Ocean Worlds,” was funded by the NASA Astrobiology Program (award #80NSSC19K1427) and the National Science Foundation (OCE-1924384).

Sustaining Hydrothermal Circulation With Gravity Relevant to Ocean Worlds, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets (open access)

astrobiology

Full paper here:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2023JE008202

https://astrobiology.com/2024/05/enceladus-astrobiology-revisited.html

Enceladus: Astrobiology Revisited

By Keith Cowing

Status Report

Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences

May 14, 2024

Astrobiology research seeks to understand how life begins and evolves, and to determine whether life exist elsewhere in the universe. The discovery of diverse ocean worlds has significantly expanded the number of planetary bodies in the Solar System that could potentially contain life.

Of the recognized ocean worlds, Saturn’s moon Enceladus stands out because it appears to meet all requirements to sustain life. For that reason, robotic mission concepts are being developed to determine whether Enceladus’ ocean is inhabited.

The theory of organic chemical evolution (OCE) represents an ideal framework to guide this exploration strategy, articulating investigations and associated measurements of organic matter in the subsurface ocean. Within this reference frame, the immediate priority with the lowest science risk would be to understand molecular and structural properties of bulk organic matter in the ocean, and search for metabolic precursors and biochemical building blocks, both free and bound.

This could be supplemented with “high-risk, high-reward” searches for functional polymers, catalytic activity, and cell-like objects with traits indicative of evolutionary adaptations. The theory of OCE provides a robust scientific foundation for the astrobiological exploration of ocean worlds, fostering a productive path to discovery with lower mission risk that could be implemented with existing technology. Strong synergies between astrobiology and Earth-bound research could ensue from this exploration strategy particularly in the context of terrestrial analog studies and laboratory simulations.

Schematic representation of the main steps in the theory of organic chemical evolution (OCE). In Stage 1, simple inorganic precursors exploit free energy to form small organic molecules. In Stage 2, reactions between small organic and inorganic molecules and minerals generates biochemical building blocks. In Stage 3, biochemical building blocks undergo condensation reactions and form small organic polymers. In Stage 4, organic polymers become structurally complex and display emergent autocatalytic properties such as the ability to self-replicate or to sustain cyclic networks reminiscent of metabolic cycles. In Stage 5, a self-copying organic polymer would emerge that can make (inexact) copies of itself and is susceptible to chemical alterations (mutations).

Compartmentalization may be a prerequisite for the emergence of autocatalysis and evolution by natural selection (e.g., Deamer et al., 2002), leading to the first cells and the first cell lineages. In stage 6, competition for resources between genetic lineages can cause an explosion of forms and functions, and different cell lineages that slowly or rapidly diverge from each other. Applicable to every stage of OCE, organic materials, particularly more functionalized compounds, may encounter environmental instability after formation, making them susceptible to alteration — JGR Biogeosciences

Enceladus: Astrobiology Revisited, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences (open access)

A. F. Davila, J. L. Eigenbrode

First published: 25 April 2024

https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JG007677

Astrobiology

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2023JG007677

https://astrobiology.com/2024/12/towards-autonomous-surface-missions-on-ocean-worlds.html

Towards Autonomous Surface Missions on Ocean Worlds

By Keith Cowing

Press Release

NASA

December 7, 2024

Through advanced autonomy testbed programs, NASA is setting the groundwork for one of its top priorities—the search for signs of life and potentially habitable bodies in our solar system and beyond. The prime destinations for such exploration are bodies containing liquid water, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Initial missions to the surfaces of these “ocean worlds” will be robotic and require a high degree of onboard autonomy due to long Earth-communication lags and blackouts, harsh surface environments, and limited battery life.

Technologies that can enable spacecraft autonomy generally fall under the umbrella of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and have been evolving rapidly in recent years. Many such technologies, including machine learning, causal reasoning, and generative AI, are being advanced at non-NASA institutions.

NASA started a program in 2018 to take advantage of these advancements to enable future icy world missions. It sponsored the development of the physical Ocean Worlds Lander Autonomy Testbed (OWLAT) at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the virtual Ocean Worlds Autonomy Testbed for Exploration, Research, and Simulation (OceanWATERS) at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California.

NASA solicited applications for its Autonomous Robotics Research for Ocean Worlds (ARROW) program in 2020, and for the Concepts for Ocean worlds Life Detection Technology (COLDTech) program in 2021. Six research teams, based at universities and companies throughout the United States, were chosen to develop and demonstrate autonomy solutions on OWLAT and OceanWATERS. These two- to three-year projects are now complete and have addressed a wide variety of autonomy challenges faced by potential ocean world surface missions.

OWLAT

OWLAT is designed to simulate a spacecraft lander with a robotic arm for science operations on an ocean world body. The overall OWLAT architecture including hardware and software components is shown in Figure 1. Each of the OWLAT components is detailed below.

Figure 1. The software and hardware components of the Ocean Worlds Lander Autonomy Testbed and the relationships between them. NASA/JPL – Caltech

The hardware version of OWLAT (shown in Figure 2) is designed to physically simulate motions of a lander as operations are performed in a low-gravity environment using a six degrees-of-freedom (DOF) Stewart platform. A seven DOF robot arm is mounted on the lander to perform sampling and other science operations that interact with the environment. A camera mounted on a pan-and-tilt unit is used for perception.

The testbed also has a suite of onboard force/torque sensors to measure motion and reaction forces as the lander interacts with the environment. Control algorithms implemented on the testbed enable it to exhibit dynamics behavior as if it were a lightweight arm on a lander operating in different gravitational environments.

Figure 2. The Ocean Worlds Lander Autonomy Testbed. A scoop is mounted to the end of the testbed robot arm. NASA/JPL – Caltech

The team also developed a set of tools and instruments (shown in Figure 3) to enable the performance of science operations using the testbed. These various tools can be mounted to the end of the robot arm via a quick-connect-disconnect mechanism. The testbed workspace where sampling and other science operations are conducted incorporates an environment designed to represent the scene and surface simulant material potentially found on ocean worlds.

Figure 3. Tools and instruments designed to be used with the testbed. NASA/JPL – Caltech

The software-only version of OWLAT models, visualizes, and provides telemetry from a high-fidelity dynamics simulator based on the Dynamics And Real-Time Simulation (DARTS) physics engine developed at JPL. It replicates the behavior of the physical testbed in response to commands and provides telemetry to the autonomy software. A visualization from the simulator is shown on Figure 4.

Figure 4. The dynamics simulator visualization showing the deployment and performance of the scooping operation. NASA/JPL – Caltech

The autonomy software module shown at the top in Figure 1 interacts with the testbed through a Robot Operating System (ROS)-based interface to issue commands and receive telemetry. This interface is defined to be identical to the OceanWATERS interface. Commands received from the autonomy module are processed through the dispatcher/scheduler/controller module (blue box in Figure 1) and used to command either the physical hardware version of the testbed or the dynamics simulation (software version) of the testbed.

Sensor information from the operation of either the software-only or physical testbed is reported back to the autonomy module using a defined telemetry interface. A safety and performance monitoring and evaluation software module (red box in Figure 1) ensures that the testbed is kept within its operating bounds. Any commands causing out of bounds behavior and anomalies are reported as faults to the autonomy software module.

Figure 5. Erica Tevere (at the operator’s station) and Ashish Goel (at the robot arm) setting up the OWLAT testbed for use. NASA/JPL – Caltech

OceanWATERS

At the time of the OceanWATERS project’s inception, Jupiter’s moon Europa was planetary science’s first choice in searching for life. Based on ROS, OceanWATERS is a software tool that provides a visual and physical simulation of a robotic lander on the surface of Europa (see Figure 6).

OceanWATERS realistically simulates Europa’s celestial sphere and sunlight, both direct and indirect. Because we don’t yet have detailed information about the surface of Europa, users can select from terrain models with a variety of surface and material properties. One of these models is a digital replication of a portion of the Atacama Desert in Chile, an area considered a potential Earth-analog for some extraterrestrial surfaces.

Figure 6. Screenshot of OceanWATERS. NASA/AMES

JPL’s Europa Lander Study of 2016, a guiding document for the development of OceanWATERS, describes a planetary lander whose purpose is collecting subsurface regolith/ice samples, analyzing them with onboard science instruments, and transmitting results of the analysis to Earth.

The simulated lander in OceanWATERS has an antenna mast that pans and tilts; attached to it are stereo cameras and spotlights. It has a 6 degree-of-freedom arm with two interchangeable end effectors—a grinder designed for digging trenches, and a scoop for collecting ground material. The lander is powered by a simulated non-rechargeable battery pack. Power consumption, the battery’s state, and its remaining life are regularly predicted with the Generic Software Architecture for Prognostics (GSAP) tool.

To simulate degraded or broken subsystems, a variety of faults (e.g., a frozen arm joint or overheating battery) can be “injected” into the simulation by the user; some faults can also occur “naturally” as the simulation progresses, e.g., if components become over-stressed. All the operations and telemetry (data measurements) of the lander are accessible via an interface that external autonomy software modules can use to command the lander and understand its state.

(OceanWATERS and OWLAT share a unified autonomy interface based on ROS.) The OceanWATERS package includes one basic autonomy module, a facility for executing plans (autonomy specifications) written in the PLan EXecution Interchange Language, or PLEXIL. PLEXIL and GSAP are both open-source software packages developed at Ames and available on GitHub, as is OceanWATERS.

Mission operations that can be simulated by OceanWATERS include visually surveying the landing site, poking at the ground to determine its hardness, digging a trench, and scooping ground material that can be discarded or deposited in a sample collection bin. Communication with Earth, sample analysis, and other operations of a real lander mission, are not presently modeled in OceanWATERS except for their estimated power consumption. Figure 7 is a video of OceanWATERS running a sample mission scenario using the Atacama-based terrain model.

Figure 7. Screenshot of OceanWATERS lander on a terrain modeled from the Atacama Desert. A scoop operation has just been completed. NASA/AMES

Because of Earth’s distance from the ocean worlds and the resulting communication lag, a planetary lander should be programmed with at least enough information to begin its mission. But there will be situation-specific challenges that will require onboard intelligence, such as deciding exactly where and how to collect samples, dealing with unexpected issues and hardware faults, and prioritizing operations based on remaining power.

Results

All six of the research teams funded by the ARROW and COLDTech programs used OceanWATERS to develop ocean world lander autonomy technology and three of those teams also used OWLAT. The products of these efforts were published in technical papers, and resulted in development of software that may be used or adapted for actual ocean world lander missions in the future. The following table summarizes the ARROW and COLDTech efforts.

Acknowledgements: The portion of the research carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology was performed under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NM0018D0004).

The portion of the research carried out by employees of KBR Wyle Services LLC at NASA Ames Research Center was performed under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80ARC020D0010). Both were funded by the Planetary Science Division ARROW and COLDTech programs.

Project Leads: Hari Nayar (NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology), K. Michael Dalal (KBR, Inc. at NASA Ames Research Center)

Sponsoring Organizations: NASA SMD PESTO

Astrobiology

You and I, we must dive below the surface

A world of red neon and ultramarine

Shining bridges on the ocean floor

Reaching to the alien shore

While the paper claims to be a model of the Enceladan ocean, it does not seem to fit with the evidence of Europa’s surface features, where ice floes have moved against each other as evidenced by surface features. I am not clear why the plumes would be only composed of old ocean water due to stratification with highly degraded organic matter, rather than newer, deep water driven by heat/salinity gradients that “punch through” the water layers, rather than just transmitting some sort of pressure wave.

Unfortunately, we will not know the truth of these subsurface oceans until we can use instruments, either locally (like traditional oceanography techniques) or remotely from orbit with em techniques (that I am not familiar with).

Hi Paul

A very interesting post once again, and Ive downloaded the paper to read too.

Good to see you back posting once again.

Cheers Ed

Overhead the albatross

Hangs motionless upon the air

And deep beneath the rolling waves

In labyrinths of coral caves

The echo of a distant time

Comes willowing across the sand

And everything is green and submarine

And no one showed us to the land

And no one knows the where’s or why’s

But something stirs and something tries

And starts to climb toward the light

We may find

microbial Rip van Winkles and Methuselahs elsewhere.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.02451

[Submitted on 4 Mar 2025]

No Robust Statistical Evidence for a Population of Water Worlds in a 2025 Sample of Planets Orbiting M Stars

Silke Dainese, Simon H. Albrecht

The study of exoplanets has led to many surprises, one of which is the discovery of planets larger than Earth yet smaller than Neptune, super Earths and gas dwarfs. No such planet is a member of the Solar System, yet they appear to be abundant in the local neighbourhood. Their internal structure is not well understood.

Super Earths presumably are rocky planets with a thin secondary atmosphere, whereas gas dwarfs have a substantial (by volume) primary H/He atmosphere.

However, conflicting evidence exists regarding the presence of a third class of planets, so-called water worlds, which are hypothesised to contain a significant mass fraction of water in condensed or steam form.

This study examines the evidence for water worlds and presents a sample of 60 precisely measured small exoplanets (less than 4 Earth radii) orbiting M dwarf stars.

We combine observational data and unsupervised machine-learning techniques to classify these planets based on their mass, radius, and density. We individually model the interior of each planet using the ExoMDN code and classify them into populations based on these models.

Our findings indicate that the sample divides into two distinct planet populations, with no clear evidence supporting the existence of water worlds in the current dataset.

Comments: 11 pages, 8 figures, accepted for publication in A&A

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP); Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR)

Cite as: arXiv:2503.02451 [astro-ph.EP]

(or arXiv:2503.02451v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.02451

Focus to learn more

Submission history

From: Silke Dainese [view email]

[v1] Tue, 4 Mar 2025 09:56:44 UTC (4,178 KB)

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.02451