Someone asked me the other day what it would take to surprise me. In other words, given the deluge of data coming in from all kinds of observatories, what one bit of news would set me back on my heels? That took some reflection. Would it surprise me, my interlocutor persisted, if SETI fails to find another civilization in my lifetime?

The answer to that is no, because I approach SETI without expectations. My guess is that intelligence in the universe is rare, but it’s only a hunch. How could it be anything else? So no, continuing silence via SETI does not surprise me. And while a confirmed signal would be fascinating news, I can’t say it would truly surprise me either. I can work out scenarios where civilizations much older than ours do become known.

Some surprises, of course, are bigger than others. Volcanoes on Io were a surprise back in the Voyager days, and geysers on Enceladus were not exactly expected, but I’m talking here about an all but metaphysical surprise. And I think I found one as I pondered this over the last few days. What would genuinely shock me – absolutely knock the pins out from under me – would be if we learn through future observation and even probes that Proxima Centauri b is devoid of life.

I’m using Proxima b as a proxy for the entire question of life on other worlds. We have no idea how common abiogenesis is. Can life actually emerge out of all the ingredients so liberally provided by the universe? We’re here, so evidently so, but are we rare? I would be stunned if Proxima b and similar planets in the habitable zone around nearby red dwarfs showed no sign of life whatsoever. And of course I don’t limit this to M-class stars.

Forget intelligence – that’s an entirely different question. I realize that my core assumption, without evidence, is that abiogenesis happens just about everywhere. And I think that most of us share this assumption.

The universe is going to seem like a pretty barren place if we discover that it’s wildly unlikely for life to emerge in any form. I’ve mentioned before my hunch that when it comes to intelligent civilizations, the number of these in the galaxy is somewhere between 1 and 10. At any given time, that is. Who knows what the past has held, or what the future will bring? But if we find that life itself doesn’t take hold to run the experiment, it’s going to color this writer’s entire philosophy and darken his mood.

We want life to thrive. Notice, for example, how we keep reading about potentially habitable planets, our fixation with the habitable zone being natural because we live in one and would like to find places like ours. Out of Oxford comes a news release with the headline “Researchers confirm the existence of an exoplanet in the habitable zone.” That’s the tame version of more lively stories that grow out of such research with titles like “Humans could live here” and “A Home for ET.” I’m making those up, but you know the kind of headlines I mean, and they can get more aggressive still. We hunger for life.

Here’s one from The Times: “‘Super-Earth’ discovered — and it’s a prime candidate for alien life.’” But is it?

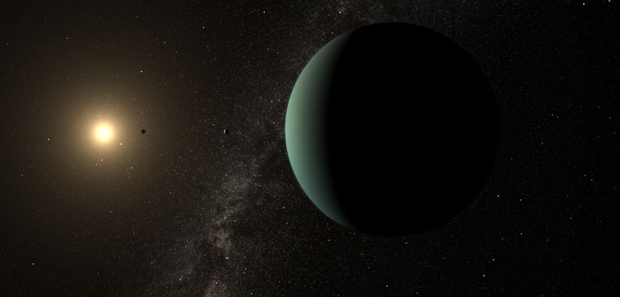

Image: Artist’s depiction of an exoplanet like HD 20794 d in a conceivably habitable orbit. It may or may not be rocky. It may or may not be barren. How much do our expectations drive our thinking about it? Credit: University of Oxford.

That Oxford result is revealing, so let’s pause on it. HD 20794 d is about 20 light years from us, orbiting a G-class star like the Sun, which gives it that extra cachet of being near a familiar host. Three confirmed planets and a dust disk orbit this star in Eridanus, the most interesting being the super-Earth in question, which appears to be about twice Earth’s radius and 5.8 times its mass. The HARPS (High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher) and ESPRESSO spectrographs at La Silla (Chile) have confirmed the planet, quite a catch given that the original signal detected in radial velocity studies was at the limit of the HARPS spectrograph’s capabilities.

Habitable? Maybe, but we can’t push this too far. The paper notes that “HD 20794 d could also be a mini-Neptune with a non-negligible H/He atmosphere.” And keep an eye on that elliptical orbit, which means climate on such a world would be, shall we say, interesting as it moves among the inner and outer edges of the habitable zone during its 647-day year. I think Oxford co-author Michael Cretignier is optimistic when he refers to this planet as an ‘Earth analogue,’ given that orbit as well as the size and mass of the world, but I get his point that its proximity to Sol makes this an interesting place to concentrate future resources. Again, my instincts tell me that some kind of life ought to show up if this is a rocky world, even if it’s nothing more than simple vegetation.

Because it’s so close, HD 20794 d is going to get attention from upcoming Extremely Large Telescopes and missions like the Habitable Worlds Observatory. The level of stellar activity is low, which is what made it possible to tease this extremely challenging planetary signal out of the noise – remember the nature of the orbit, and the interactions with two other planets in this system. Probing its atmosphere for biosignatures will definitely be on the agenda for future missions.

Obviously we don’t know enough about HD 20794 d to talk meaningfully about it in terms of life, but my point is about expectation and hope. I think we’re heavily biased to expect life, to the point where we’re describing habitable zone possibilities in places where they’re still murky and poorly defined. That tells me that the biggest surprises for most of us will be if we find no life of any kind no matter which direction we look. That’s an outcome I definitely do not expect, but we can’t rule it out. At least not yet.

The paper is Nari et al., “Revisiting the multi-planetary system of the nearby star HD 20794 Confirmation of a low-mass planet in the habitable zone of a nearby G-dwarf,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 693 (28 January 2025), A297 (full text).

I wouldn’t be shocked to not find life on any one habitable zone (and habitable) planet. I would be shocked to find none. Noting of course that proving a negative is difficult, especially from light years distance.

There were have to be something fundamentally important going on, and surprising, if life is so rare that we are alone or perhaps almost alone. Even if what we find is nothing more than primitive life. Abiogenesis should not be that difficult.

It is difficult to be surprised by something not happening, of course, so at least you will never be subject to a sudden shock, more like a slow realization!

Myself, I would be very surprised if we did discover extraterrestrial life, for one very simple reason:

There is no such thing as “simple life”. Anything we know that can grow and multiply is incredibly complex. There must have been simpler intermediates, once, but we don’t see them, today. We can only speculate about their nature.

“simple” life means single-cell organisms, like bacteria and single-cell algae.

“complete” life means organisms with many differentiated cells, i.e. almost all life larger than unicellular organisms.

It is now believed that the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) to all life on this planet was quite close in its complexity and functions to that of bacteria and archaea.

Any “life” or “pre-life” prior to, or contemporaneous with, LUCA was likely selected against by natural selection and no longer leaves any trace that we can currently observe. If we accept abiogenesis occurred on Earth, there must have been a period when there was no life, then a period of some components appearing, then consolidation into very primitive cells, before LUCA appeared. Maybe we can find evidence of these stages elsewhere. OTOH, if LUCA’s early appearance was due to panspermia, then such abiogenesis stages would only have appeared elsewhere in the universe. Perhaps a deity’s lab to take Mike S’s earlier comment down thread?

I think that Mars is a bit of a litmus test.

We should get a LOT of data from there in the coming years and if there are zero signs of present or past life, I think we are likely looking at a barren universe rather than a fecund one.

Yeah, like if Mars had plate tectonics in its deep past.

If we assume life starts fast, as long as there are the precursors and conditions for life, then Mars likely had a sufficient window… The fact that it is not (obviously) present now is a worry and I wonder if it hints at a filter…

Either way there should be some hint of life there, past or present. If after 10 years of looking in caves and drill samples there is still no hint, it could imply that life is exceedingly rare.

My guess is that HD 20794 d is, at minimum, a waterworld with a planetary ocean at least 100km deep and possibly as deep as a 1000km. It will have a very thick, dense atmophere with a surface pressure of 100atm and possibly up to 1000atm. This is dense enough that the planet may not have a sharply definable surface. Rather, the atmosphere gradualy merges into the ocean, analogous to a mini-Neptune. I think it highly unlikely HD 20794 d is even remote habitable to humans.

An ocean that deep leaves little chance of the weathering and erosion that resulted in our oceans being salty. It is all the dissolved materials that make our seas salty that allows for lots of biomass to form. The planetary ocean of HD 20794 d is likely to be as pure as the distilled water you use in you Keurig coffee maker. This is not conducive to life. What life that exists on this planet, if any, will likely be limited to the areas around the hydrothermal vents it emerged from and will be prokaryotic.

We have to look much more to find real habitable planets.

One more thing. Does HD 20794 d have planet tectonics? Tectonics allows for the controlled release of all that energy and heat in the planet. No plate tectonics, no controlled release. Instead, you get the period crustal resurfacing that make Venus what it is. Does the rocky core of Neptune have plate tectonics? I’ve heard Neptune has winds of speeds up to 900 mph. Could period crustal overturn of the rocky surface be the source of energy for these winds?

Instead of HD 20794 d being a super-earth, it could be a super-Venus. Certainly not an abode of life as we know it.

Complexity seems to arise naturally, spontaneously, out of the fabric of space-time itself. As long as there is some pocket of energy available, entropy can be reversed. The question is, is this property limited to the tools and matter available, or can it manifest itself in alternative ways with alternative materials? To put it another way, is carbon-water life the only life, or are there biologies and communities of silicon, ammonia-breathers, cryogenic supercooled crystalline creatures, life forms of plasma or electromagnetic fields, perhaps entities composed of interfering gravity waves?

Are there other kinds of life? Are ‘other kinds of life’ possible? Are alternative biologies even necessary? Are alien ecosystems and communities, if they exist, a lucky accident due to the same physical laws operating on the periodic table? Or are these alternatives inevitable, due to some fundamental property of space-time itself?

I am taking a beginner’s course now in molecular biology and I find it inconceivable that the subtle processes of life could be carried out in any other way than the familiar reactions we are now familiar with. But I I also know enough about the history of science to realize what a hopelessly provincial and short-sighted statement that is!

Newton’s Laws of Gravity are remarkably concise, and yet we are discovering highly subtle processes and structures visible in orbital resonances which (although an obvious result of those Laws) were totally unexpected. Its almost as if the universe has a built-in property that allows, or even forces, it to create complex relationships and events from simpler ones And Newton’s Laws, although now supplanted by Relativity, can easily explain and describe these resonances.

The search for extra-terrestrial life isn’t just about whether or not evolution has created critters on other planets. It is an inquiry into the nature of reality itself.

How sure are you that you’re not mixing up disappointment with surprise? Study on the start of life seems to have a very long way to go, I personally wouldn’t be surprised not to see quick signs of primitive life.

If in the next decade or so, if we do not detect fairly unambiguous biosignatures, I won’t be surprised, but I will be disappointed, especially regarding the implications. IMO, it would indicate that the fanciful idea of finding other homes for humanity in “Earth-like” worlds is a no-go without extensive terraforming. It should increase the emphasis on preserving Earth, although there is little sign of that currently.

What would surprise me is alien ships appearing in Earth’s skies, or landing in places near various major national government buildings and wishing to address their nations. [If they claim they have been visiting us for centuries in their ships and with their probes, I will apologize to the Ufologists.]

Given our current understanding of physics, I would be [very] surprised if we make a sudden breakthrough allowing FTL flight. That could be a game-changer.

Having aliens turn up in our solar system or discovering some form of FTL would do the stop in your tracks surprise thing for me. Rather than finding a lifeless Proxima B.

To me, finding clear evidence of life on Proxima B would be more surprising than the other way around.

Proxima b may have had its atmosphere blown off by solar flares and its oceans evaporated as part of the process. If, as seems highly likely, it has synchronous rotation then, once the atmosphere thins down to < 100 mbar, the last dregs of the planet’s volatiles will collapse onto an ice cap of water, CO2, and nitrogen ice on the dark side. So, we are left with a barren and hot light side, an an extremely cold dark side. Possibilities are left for microbes to survive somewhere, but we may never know unless we actually visit, land, and drill down deep. Thus, I would not be surprised at all if no life is discovered on Proxima b.

An interesting paper utilizes DYNAMITE analysis of the 82 G. Eridani (HD 20794) system, revealing a candidate planet referred to as planet f, which is located in the habitable zone.

The title of the paper is “An Integrative Analysis of the Rich Planetary System of the Nearby Star e Eridani: Ideal Targets for Exoplanet Imaging and Biosignature Searches.” https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.06250

The concept of panspermia suggests that life could be common, particularly in ocean worlds, as this scenario would create optimal conditions for the evolution of life. Colonies on such worlds might evolve rapidly, much like Homo sapiens, who took only 300,000 years to develop into the diverse range of humans we see today.

With current technology, large ships would require at least a hundred years to reach 82 G. Eridani. This raises the question: would such long journeys lead to the emergence of many evolving worlds for any civilizations that choose to advance their genes beyond their home planet?

“What Would Surprise You?” when I saw that title I thought you were referring to current events around the world and in that case due to the last few years nothing much does surprise me these days.

I actually agree with Martyn here and a lot of these Planets around smaller red dwarfs are going to be hot on the day side with a giant ice cap on the night side, perhaps under a deep side night cap a layer of water could exist where you might find an ecosystem like lake Vostok, there is no chance of an Earth like biosphere.

Abelard Lindsey has it right too I’ve had the same opinion that these super earths are not the ideal places for life to arise.

For an advanced civilization from another star system could be an ideal place to build a habitat in a rind around the terminator.

I did read the paper on this planet, its size and mass place it in the Super earth Ocean type of world So its not going to be earth like and One could assume the ocean and atmosphere moderate the temperatures on the orbit.

Cheers Edwin

RE:

“Planets around smaller red dwarfs are going to be hot on the day side with a giant ice cap on the night side,”

Don’t know if this would be a consolation or not. But if water boils away on the roasted side and is carried over to the night side, the three dimensional distribution of matter might perturb the synchronous rotation enough that over millennia long periods, the axis of rotation would be perturbed and or shifted.

It just might be difficult to maintain the synchronous equilibrium over long periods of time. If the axis wobbles, the high latitudes would experience exposure and and angular rates could change too since the distribution of momentum would no longer be “one dimensional”. Of course if all the fluid elements evaporate into space – say after several billion years – the result is much the same, save for the discoveries of future exo-geological surveys. But even amid all that hydrodynamics of accumulation and evaporation, there might have been an

opportune period for biological activity. Much like there might have been ages ago on Mars, for example.

I would be very surprised if any of our current models for exoplanet habitability (and uninhabitability) survive contact with reality.

What will surprise almost everyone but me: benchtop abiogenesis. I don’t think the chemical compounds needed to initiate life were stable enough for the process to take long, so I think that if you bring together the right components (I’m guessing hydroxylapatite, maybe polyphosphates, formaldehyde, ammonia … and some things I don’t know about!), you can create a whole new origin of life – a genuinely “alien” life form! – in an afternoon. Understanding abiogenesis – the conditions needed, how hard it is, and especially, the range of different self-replicating nucleic acids that can result – well, that gives us a much clearer idea of the conditions needed for life to originate in the cosmos.

What will surprise me and everyone is communication with another species. We’ve been trying to do this for ages, since the first nominal member of the human genus tried to talk to a crow. We’re starting to see some claims of minor success. Question is … can AI-level resources really make it possible for us to understand such conversations as much as they can be understood? Inevitably we’ll be surprised by what animals either know or don’t know, think or don’t think, and it will help us prepare a bit for what lies beyond.

If that were true, wouldn’t the needed conditions have at least sporadically reoccurred over 4bn years to put truly alien life on Earth, at a minimum, in refuges or, as Davies says, create a “shadow biosphere”?

Maybe we haven’t looked in every possible refuge to find this life, or there are no places that can evade the predation by our LUCA-based life. Maybe the magic ingredients are so rarely in the same place and time that life has not appeared everywhere we look in space, otherwise it should be ubiquitous.

If life is that easy to create, then alien life will likely not be like terrestrial life, assuming that evolution doesn’t select everywhere for our form of life as the “most fit”.

When we can send probes or ships to the stars, a test of this hypothesis would be to look at every extremely young planet ( less than 100 my old) for signs of life. It should be ubiquitous and probably highly divergent in its biology from terrestrial life.

Superintelligent AI help may be needed to create the conditions needed in the lab. It should be a lot easier than exploring exoplanets.

So far, we haven’t seen reports of any pure RNA based life form. I doubt they have really all been driven out of existence by cellular life – more likely we don’t know what to look for. If someone drills deep into the channels of some mineral where cells cannot reach, but some primordial mix of gasses can enter, maybe they could find a branched strand of RNA containing a wide range of nucleic acid residues (I expect including riboflavin and nicotinamide) … there could be a surprise there. But it does appear that modern life has kicked down the ladder on any and all cellular protein-synthesizing organisms with genetic codes substantially different from our own. Ribosomes work about the same way in all known life (with minor exceptions of great interest to biologists).

Comparing alien to Earthly life is another question. It remains possible, I think, that life evolved somewhere other than Earth, then one or a few prokaryotes colonized the planet. In such a scenario we might find many worlds with life as similar to us as our own bacteria and archaea. This might seem to contradict my notion of easy abiogenesis, but perhaps the steps in the middle aren’t very easy. Maybe it takes many billions of years to get from RNA to ribosome, and it is just faster nowadays for one to fall out of the sky. Plenty of room for surprises. :)

Regarding RNA life:

Perhaps the closest we have is RNA viruses and non-coding transcribed RNA.

None are close to independent. The viruses need cells to replicate, although I wonder if there might be forms that do not also require a protein coat. Noncoding RNA is obviously transcribed from cellular DNA, but if there are examples that could be self-catalyzing AND these RNAs escaped the cell, would they be an example, however transient, of RNA-World [pre]life?

The earlier in Earth’s history abiogenesis is assumed to occur (and now we have 200my to reach LUCA), the more likely it seems that either abiogenesis is easy or, panspermia is the source.

That may be resolved if we find life in our system that is different from terrestrial life – abiogenesis is easy or, we have to get samples of life from an inhabited exoplanet and determine whether it is the same of different from Earth’s. We may need lots of different exoplanet samples to be fairly sure that panspermia is the source is they look the same at Earth life. This may still be ambiguous as we won’t be sure that the source of panspermia life is unique. It may be a mix of unique sources.

For me, if panspermia is the cause of the commonality of life, that would be less interesting than separate abiogenesis events. Evolution would certainly generate very different forms of complex life with unique evolutionary histories, but the intrinsic biology would be the same. Unique abiogenesis events would likely create very different biologies, at the very least, different genetic codes, but also different details of information storage, replication methods, etc.

If we find life in our system, I might still be alive to see the results. However, I will be long gone before exoplanet life samples are tested, even by remote probes, and therefore I will not see how ET life (if any) differs.

Alex, can you help me understand a topic I’m not very familiar with? Can viruses cause mutations in living organisms and potentially accelerate their evolution? I’ve noticed that researchers keep discovering many new viruses in the oceans, and that RNA viruses tend to evolve at much faster rates than DNA viruses.

Recently, scientists reported the discovery of 5,000 new viruses in the ocean, one of which could be particularly significant.

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/04/researchers-identified-over-5-500-new-viruses-in-the-ocean-including-a-missing-link-in-viral-evolution/

There’s also a new theory suggesting that in the early asteroid belt a vapor cloud of water developed and migrate to Earth.

“Conclusion: The researchers propose that viscous water transport is more common and inevitable than previously thought, surpassing the impact scenario. They believe this process could be universal, potentially occurring in other solar systems as well. The necessary conditions for this to happen are likely present in most planetary systems: an opaque protoplanetary disk that is initially cold enough for ice to form in the outer asteroid belt region, followed by a natural outward-moving snow line. This allows the initial ice to sublimate after the primordial disk dissipates, creating a viscous secondary gas disk that could lead to the accumulation of water on terrestrial planets and exoplanets.”

This suggests an impact-free mechanism for delivering water to terrestrial planets and exoplanets.

https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/abs/2024/12/aa51263-24/aa51263-24.html

This theory may relate to panspermia, as it could create a vast area in the solar system that serves as a capture mechanism for RNA and DNA life forms from other solar systems.

Viruses are truly ancient, and can be organized into large taxonomic groupings. There is an argument that several types of viruses had already evolved before the last universal common ancestor, in other words, within those few hundred million years after Earth’s formation.

Nonetheless, viruses don’t come close to counting as “RNA life”. Virus RNA is mostly described in terms of genes. It functions by being brought to a host ribosome to make proteins, or regulates genes that do. The viral RNA can’t collect energy from sunlight, catalyze biochemical reactions, or poke holes in a cell membrane.

Nobody knows what early RNA life would have looked like, but it could have predated some modern day rules – like having only four nucleotides to choose from, or being connected in a single linear 5′ to 3′ strand. I suspect it may not be coincidence that our mitochondria use NADH and FADH2 – both 5′ to 5′ nucleotides made from adenine with either flavin or nicotinamide nucleotides – and that the second halves just happen to be the two vitamins that cause sun sensitivity when taken in excess because they are prone to absorb the light and get into reactions. I also suspect that 2′ to 5′ linkages, only occasionally used in modern RNA to form branched structures, would allow the physical attachment of resources to the genome in solution before the origin of the cell membrane. I don’t have very good odds of being right, but however they worked, true RNA life forms have had to catalyze biochemical reactions directly, without access to protein synthesis.

Those viruses may well have evolved before LUCA tells us that LUCA was already an advanced cell and that its various predecessors also had the same replication systems that it, and we, have. Viruses are on that borderline of life:not-life. They cannot grow as cellular life does, and replication requires a host. But replication also cannot happen for parasites and symbionts if their hosts become extinct. Interestingly early computer simulations of life [Tierra?] showed that parasitic digital forms appeared that, like viruses, could only replicate with the help of other fully capable replicators.

Digression:

While viruses and non-coding RNA are not “RNA-Life” I would say that there never was anything we could define as life in a pure RNA world. No metabolism, just the ability to replicate and evolve, but not to bear the hallmarks of life. “Pre-life” perhaps, but even that might be too fanciful. Branching RNA may be possible, but fortunately, it does not happen, AFAIK, in cells. Any such RNA would break the DNa->RNA->protein processes. Would there be any advantage to branching RNA? Any “free-living” unbranched RNA has the opportunity to potentially be replicated. We know that DNA is readily found in the environment, whether isolated or in intact cells. Is it possible that RNA could similarly be transiently isolated in the environment, like an RNA virus without its protein coat?

Turning back to the origin of viruses, this could reduce the probability of panspermia vs abiogenesis. While it doesn’t eliminate panspermia, it might suggest that viruses co-evolved with cells, as parasites hijacking the replication mechanism of cells. That there are RNA viruses, not just DNA viruses, also suggests that they are a branch of RNA-World, while teh main branch became part of teh cellular machinery of cells, both translated to proteins and untranslated as functional macromolecules.

Digression:

Viral coats are translated viral genes. [Phage viruses are more complex in structure]. The assumption is that they must have evolved with the same genetic code as cellular life. I have wondered if their coats could still work with different proteins if a different genetic code was used. Today, we can test this using AI like DeepMind’s AlphaFold by transforming the viral coat sequences so that they reflect different genetic codes.

The RNA would have to fulfill all the features of life, including growth and replication which would be more functional than viruses. This implies at least a cell wall, and a metabolism that allows RNAenzymes to fulfill the role of protein enzymes, at least efficiently enough to avoid extinction by predation even in refuges. If such life were possible, perhaps it could be found on worlds where terrestrial-like life has yet to fully emerge but has advanced beyond simple RNA self-replication or metabolic circuits.

I think the RNA World was very much alive, but I think we should try to think back to before there were cells, or viruses, or species, or organisms. In my mind, at the beginning I’m picturing an exposed hydroxylapatite surface with calcium and phosphate ions in a crystal structure, and trailing off those phosphate ions we have short RNA-like nucleic acid strands. A strand bends back to the surface now and then, finds a short complementary strand, which is replicated onto that template, like Illumina sequencing. But these aren’t just data tapes – the RNA folds up and carries out reactions. One catalyzes some step of formose condensation of formaldehyde, another brings ammonia onto a 1′ position of a ribose, another uses CO2 to build up a ring of a nucleic acid base, etc. etc. Each strand is an “organism”, seeking to replicate its genetic code, but it is “parasitic” on the others, since it doesn’t have close to all the enzymatic activities it needs. There is no package around these genes; it’s a free-for-all, but one where mutualistic symbiosis should win the day.

Eventually these things should get away from the mineral deposit. I picture phosphate, divorced from its parent mineral, as the point where the compounds most often stick together at the conceptual level. It is a point where nucleotide, glucose, triose, phospholipid, even phosphoaspartate could all be tethered one to another, in a diversity of arrangements. RNA with a 2′ branch sitting in its major groove can still be copied, although it is more prone to mishap. So this represents a way to tack all sorts of luggage onto an RNA strand without completely ruining its genetic function.

I picture the covalently bound luggage as necessary because there is indeed no cell membrane (or capsid or wall of any sort) near the beginning. At some point in an RNA-first scheme, ribose starts getting repurposed: I picture moving some oxygens to make it into aspartate; the dicarboxylic acids chelate the Ca++ and represent the beginning of something vaguely akin to a Krebs cycle. Get rid of all the oxygen and you can do fatty acid synthesis (notice that CoA is just another weird 5′-5′ dinucleotide!); when you do this around a phosphate anchor, that’s a phospholipid. I think such a structure could form some partial phosphate monolayer for nutrition or protection long before the machinery for an entire cell is feasible. Throw in some light-absorbing nucleotides to power some of these reactions and now you’re really cooking.

This youtube video is a good summation of what an ocean world would be like. It is about Kepler 22-b.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Dex82WT7Y0

it is as yet unclear to me how the mass and radius values for HD 20794 d were derived. Perhaps with some additional reading of the text it will be more clear.

But for starters concerning a presumed habitable exoplanet, an Earth analog in density at 2 Earth radii would have 8 x the mass of Earth. vs. 5.8.

Some interaction with other planets transits would be a mass indicator, but this planet is highly eccentric vs. the instances where transit time delays are observed.

But if the radius and mass are as indicated, the surface gravity would be about 1.25 g’s. If it rotates at a substantial rate, equatorial visitors would get an additional break. What the rotational rate would be on a large planet in an

eccentric orbit would be an interesting tale in itself. Precession would be a bigger deal there than here on Earth.

Now and then we do tend to hold exoplanet sites up to the two differing explanations for life’s possible origins, if it would exist at all: eventually originating in isolation due to chemistry – or else arriving well on its way to “life” from elsewhere.

The local explanation for our existence seems to suggest seems to suggest something like winning a galactic or even a galactic cluster lottery.

The arrival of basic pre-assembled components – whatever they are – might raise the chances to see something elsewhere. My suspicion is the latter, though there might be a whole lot of poor ground to sow the seeds.

A recent development in this regard is the analysis of the Bennu return capsule.

For as long as Bennu and Earth have been on distant terms, the analyses thus far indicate that the nucleic acids resident on this small asteroid clump provide a remarkable starter set. Materials on Bennu – though not swimming in one now – were once part of a body with a lake of some sort, a lake not entirely pristine.

And so it seems to go. Because time intervals associated with Bennu go back to the earliest epochs of the solar system. The solar system likely originated in a condensing gas and dust cloud with not well defined boundar but resulting in both stars and numerous small solid and liquid bodies… And my point is that the handoff of precursor materials from Bennu, which was passed on to Bennu by a friend, could be typical of a process going on in favorable regions of the galaxy.

And, given that Earth was bombarded in some fashion with such precursors, I argue that Earth’s experience might not be so unique as the abiogenesis model

implies. Some places it went worse, some better. Later or earlier.

Being in an inhabited galaxy seems more appealing than an empty one. Perhaps at the very least as much as having a metal detector turn up something interesting on what had looked like an empty, sandy beach.

WDK said…

“…an Earth analog in density at 2 Earth radii would have 8 x the mass of Earth. vs. 5.8.”

Perhaps the discrepancy arises only if the mass of the planet were equally distributed throughout its volume. On both the Earth and (presumably) this world, a proportionally greater mass is concentrated in the core. For example, on our own world, with a iron core and rocky outer layers, the density of the mantle and crust is lower than the average density of the planet as a whole, while the density of the core is higher than the average density.

It is may be possible to make meaningful direct estimates of a exoplanet’s overall mass and radius using purely astronomical methods, but just how that mass is distributed below the surface would depend on additional assumptions about its composition and structure.

I make no claim to have any valid opinion here. But I marvel, Paul, at the profundity of your nuanced analysis … of all this future ‘stuff’, which most of us might never see. I sense a J G Ballard melancholia, which makes me sad. But I totally get what you are thinking.

The possibility of life, or intelligence in the cosmos is of more than pure scientific interest; it also has profound philosophical and even theological implications. If the natural processes that led to life and consciousness on Earth are merely the manifestation of simple natural law, then we are simply one of a plurality of worlds.

But if we learn the rest of the universe is devoid, or nearly so, of living things and sentient beings, all sorts of troubling questions arise. These are questions that we’ve been struggling to answer since the Bronze Age, and which, so far, our latest science has been powerless to resolve. If life and intelligence are common in the universe, just a result of astronomical and chemical processes, then we live in a very different reality than one in which we are alone.

I know this is why I am attracted to the field, my own prejudices lead me to a mechanistic, materialistic solution. If we are indeed alone, something else is going on, something which I am hesitant to embrace. I suspect this nagging doubt is what motivates all of us to pursue these speculations.

Finding evidence of life, or a civilization, especially nearby, will tell us we live a scientific universe. If we are indeed alone, we live in a very different reality.

I don’t think a Proxima b devoid of life would shock me. I don’t think we can expect all HZ M dwarf Earths to be not only habitable, but also inhabited – at least, this is what finding life on Proxima b would imply. Unless panspermia has a big role to play in the distribution of life in the universe (and I don’t see any signs it has), there is no reason to expect that abiogenesis will happen everywhere. Abiogenesis might require more than available energy, certain elements and liquid water (but we will be able to test that in the next decades on the icy moons – if they are devoid of life, why would Proxima b not be, too?). What would truely suprise (even shock) me would be to find macroscopic animal life on Proxima b. It would mean that even complex lifeforms are not rare, which would move the “Great Filter” very close to us, i.e., self-destruction of some form being the most common end for civilizations.

About ocean planets such as (probably) the one under discussion: for me (a layman) the most sobering realization in the last 20 years of reading about exoplanets and the factors that go into making them potentially habitable, is that there is such a wide range of quantities of water that could be present on the surface of a planet, that it is exceedingly unlikely for a planet to have both extensive oceans and extensive landforms, similar to our continents and coastlines. Ten times less water than us, and we have just a few puddles. Ten times more water, and there’s no land anywhere. And a factor of ten is nothing–there could be anywhere from thousands of times more water delivered to the surface of a planet, to less than a thousandth. So it seems that the chances of another planet having continents and coastlines like ours–with a big enough ocean to support the development of primitive life and supply emerging civilizations with their water needs, but also enough land for emerging civilizations to flourish–are tiny.

If someone knows of a counterargument, it would cheer me up! Otherwise, I’d be surprised if: we managed to get gravitational-lens-based imaging up and running within my lifetime, and resolved an exoplanet with both large oceans and large landmasses.

Did you see the post The Odds on an Empty Cosmos about the low probability of the possible fine-tuning needed for life?

I see what you mean! There’s a very steep S curve, with very long tails at the “not enough water” and “too much water” ends, and only a very narrow band centered around “juuuuust right” where we get reasonable/interesting amounts of coastline. And this is analogous to the overall odds of life being widespread — it’s very unlikely we find ourselves on that knife edge. (In the case of planetary quantites of water, though, we are pre-selected — by virtue of existing — to be somewhere around that knife-edge.)

JonW,

Reading your review of exoplanet water which included some lament, if it is of any help:

It might be worth not ruling out the amount of water that might exist under surfaces that look or are determined to be quite dry. Some of the mysteries of geology here on Earth might be explained by rises and drops of surface water connected to an internal reservoir. Because when one thinks about it it seems unreasonable to think the bottom of the ocean is wet, but dry on the other side of the floor. It could be wet for a considerable distance down whether the aquifer ever breaks through to the surface. In Texas a possible illustration would be the Edwards Plateau.

And reasons for that oscillation (rather than just a process of just vanishing into space) could be internal heating intervals and then relative cooling. It sounds weird at first examination, but if the interior is not entirely static, then there might be intervals of geological history when more heat or energy tended to escape.

For example, if the internal radius for superheated steam shifted up, subsurface water would be driven up and outward too. The radius reduces and it subsides.

Even Mars might have an element of such behavior, though I suspect that its sea faring days were a couple billion years back. But it seems clear that there is both subsurface water now and a long history of evaporation into space. Go farther out in the solar system and a place like Ceres probably has internal water reserves still too. It might have had a gusher just before the Dawn spacecraft arrived.

Consequently, considering that the majority of stars are red dwarfs and that they are not all the same number of billion years old, there might be a few that retain or else produce an atmosphere faster that the primary can blow it away. And for the ones that are crowded with terrestrial planets, even if these eras are relatively short geologically, these oases in time and space might be interesting to explore or sojourn on for a millennium or two, And if there are no natural means to replenish, then maybe local Kuiper or Oort belt material can supplement local resources.

Beyond that conjecture we need to consult with people who think in more detail about the longer term.

What would surprise me is if ‘we’ find no evidence of any other life in our own solar system other than on earth, in my lifetime. My expectation and belief is there must be (or was in the past) at least other microbial life in our home system. It would be difficult to prove there isn’t and never has been any other life (especially microbial) in our solar system, but not finding any evidence of it within the next 10 to 20 years (hopefully) would surprise me.

My two cosmic-level surprises would be…

1. That we are alone in the Universe, which naturally includes the Milky Way galaxy. Intelligent life as we currently recognize it might be problematic, but even the Rare Earthers have said they expect microorganisms to be plentiful throughout the Cosmos.

2. That humanity is somehow the most important species and the focal point of salvation when it comes to existence. We are but one of many. Even if we are one of the few intelligent species around, that would just make us an even tinier part of the Cosmos with our form of life being of little influence on anything else for a long time, if ever. Humans still think emotionally they are the center of existence and cannot grasp just how vast and ancient the Universe is.

And if there really is a Multiverse of infinite alternate realities, look out!

Here are some very recent news items on the subject:

https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/does-planetary-evolution-favor-human-life-study-ups-odds-were-not-alone

https://www.livescience.com/space/extraterrestrial-life/perhaps-its-only-a-matter-of-time-intelligent-life-may-be-much-more-likely-than-first-thought-new-model-suggests

To quote from the first linked item:

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Humanity may not be extraordinary but rather the natural evolutionary outcome for our planet and likely others, according to a new model for how intelligent life developed on Earth.

The model, which upends the decades-old “hard steps” theory that intelligent life was an incredibly improbable event, suggests that maybe it wasn’t all that hard or improbable. A team of researchers at Penn State, who led the work, said the new interpretation of humanity’s origin increases the probability of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe.

“This is a significant shift in how we think about the history of life,” said Jennifer Macalady, professor of geosciences at Penn State and co-author on the paper, which published today (Feb. 14) in the journal Science Advances. “It suggests that the evolution of complex life may be less about luck and more about the interplay between life and its environment, opening up exciting new avenues of research in our quest to understand our origins and our place in the universe.”

Link to the above-mentioned paper here:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ads5698