When it comes to oceans beneath the surface of icy moons, Europa is the usual suspect. Indeed, Europa Clipper should have much to say about the moon’s inner ocean when it arrives in 2030. But Titan, often examined for the possibility of unusual astrobiology, has an internal ocean too, beneath tens of kilometers of ice crust. The ice protects the mix of water and ammonia thought to be below, but may prove to be an impenetrable barrier for organic materials from the surface that might enrich it.

I’ve recently written about abused terms in astrobiological jargon, and in regards to Titan, the term is ‘Earth-like,’ which trips me every time I run into it. True, this is a place where there is a substance (methane) that can appear in solid, liquid or gaseous form, and so we have rivers and lakes – even clouds – that are reminiscent of our planet. But on Earth the cycle is hydrological, while Titan’s methane mixing with ethane blows up the ‘Earth-like’ description. For methane to play this role, we need surface temperatures averaging −179 °C. Titan is a truly alien place.

In Titan we have both an internal ocean world and a cloudy moon with an atmosphere thick enough to keep day/night variations to less than 2 ℃ (although the 16 Earth day long ‘day’ also stabilizes things). It’s a fascinating mix. We’ve only just begun to probe the prospects of life inside this world, a prospect driven home by new work just published in the Planetary Science Journal. Its analysis of Titan’s ocean as a possible home to biology doesn’t come up completely short, but it offers little hope that anything more than scattered microbes might exist within it.

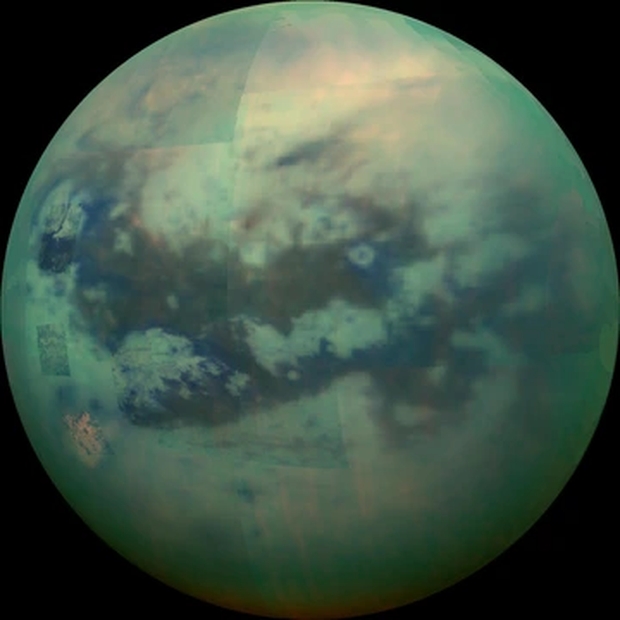

Image: This composite image shows an infrared view of Titan from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, acquired during a high-altitude fly-by, 10,000 kilometers above the moon, on Nov. 13, 2015. The view features the parallel, dark, dune-filled regions named Fensal (to the north) and Aztlan (to the south). Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/University of Idaho.

The international team led by Antonin Affholder (University of Arizona) and Peter Higgins (Harvard University) looks at what makes Titan unique among icy moons, the high concentration of organic material. The idea here is to use bioenergetic modeling to look at Titan’s ocean. Perhaps as deep as 480 kilometers, the ocean can be modeled in terms of available chemicals and ambient conditions, factoring in energy sources (likely from chemical reactions) that could allow life to emerge. Ultimately, the models rely on what we know of the metabolism of Earth organisms, which is where we have to start.

It turns out that abundant organics – complex carbon-based molecules – may not be enough. Here’s Affholder on the matter:

“There has been this sense that because Titan has such abundant organics, there is no shortage of food sources that could sustain life. We point out that not all of these organic molecules may constitute food sources, the ocean is really big, and there’s limited exchange between the ocean and the surface, where all those organics are, so we argue for a more nuanced approach.”

Nuance is good, and one way to explore its particulars is through fermentation. The process, which demands organic molecules but does not require an oxidant, is at the core of the paper. Fermentation converts organic compounds into the energy needed to sustain life, and would seem to be suited for an anaerobic environment like Titan’s. With abiotic organic molecules abundant in Titan’s atmosphere and accumulating at the surface, a biosphere that can feed off this material in the ocean seems feasible. Glycine, the simplest of all known amino acids and an abundant constituent of matter in the early Solar System, serves as a useful proxy, as it is widely found in asteroids and comets and could sink through the icy shell, perhaps as a result of meteorite impacts.

The problem is that this supply source is likely meager. From the paper:

Sustained habitability… requires an ongoing delivery mechanism of organics to Titan’s ocean, through impacts transferring organic material from Titan’s surface or ongoing water–rock interactions from Titan’s core. The surface-to-ocean delivery rate of organics is likely too small to support a globally dense glycine-fermenting biosphere (<1 cell per kg water over the entire ocean). Thus, the prospects of detecting a biosphere at Titan would be limited if this hypothetical biosphere was based on glycine fermentation alone.

Image: This artist’s concept of a lake at the north pole of Saturn’s moon Titan illustrates raised rims and rampart-like features as seen by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

More biomass may be available in local concentrations, perhaps at the interface of ocean and ice, and the authors acknowledge that other forms of metabolism may add to what glycine fermentation can produce. Thus what we have is a study using glycine as a ‘first-order approach’ to studying the habitability of Titan’s ocean, one which should be followed up by considering other fermentable molecules likely to be in the ocean and working out how they might be delivered and in what quantity. We still wind up with only approximate biomass estimates, but the early numbers are low.

The paper is Affholder et al., “The Viability of Glycine Fermentation in Titan’s Subsurface Ocean,” Planetary Science Journal Vol. 6, No. 4 (7 April 2025), 86 (full text).

As per Figure 1 of the paper, a key problem is that the ocean is locked away from both the surface and the silicate core of the moon by tens of km of ice. The authors concentrate on the surface carbon sources to power the ocean ecosystem, but suggest that there is too little penetration of organics through the ice to the ocean.

However, a key problem for life is where abiogenesis is hypothesized to occur. Unlike Earth, Europa, and Enceladus, the possible vents to hatch life on Titan are separated from the ocean by about 100 km of ice, sealing this environment from the ocean.

This suggests that any life, if appearing by abiogenesis at vents in the silicate core, would be confined between the core and the overlying ice. The vents would ensure that there were warm “puddles” at the base of the pressure frozen water ice, that could support a small vent ecosystem of microbes.

IOW, the place to look for life may not be the ocean, but in warm saline regions between the silicate core hot vents and the overlying ice that seals the ocean from the core.

Finding and penetrating any such ecosystems will make the penetration of the Europan and Enceladan surface ice crusts seem simple by comparison. It will be a very long time before our exploration technology could allow exploration of the interface between Titan’s rocky core and the ice above it.

Any life on Titan will be humans and their accompanying life support on the surface of Titan, a miserably cold environment. Even robots might have difficulty staying warm enough to operate on Titan’s surface.

If Titan was pushed out of it’s orbit early in it’s formation with advanced technology like a warp drive, etc, into the middle of the life belt, Titan today would look exactly like are Moon. Titan’s core is a little smaller than the Moon. All the oceans, and atmosphere would be lost just due to the low gravity and Jeans escape. Now we can see how unEarthlike Titan is.

Amino acids and fermentable molecules might indeed be a sign of life in the interior. There are also cryovolcanoes on Titan and their products should be also chemically analyzed. I like the idea of a lander, but spectra might be enough.

I remember the atmosphere of Titan was thought to be around 100 millibars or what we used to think was the pressure on Mars before we sent Mariner probes there. That was enough to get me to think life might be there when I was a teenager in the 1980. I was surprised that the atmosphere was found to be 1.5 bars from Voyagers radio wave attenuation test as it passed through it’s atmosphere as Voyager passed behind the planet and Also the triple point of methane being possible which is proven today. I still think we should look for life there even though I think the probability of life evolving without sunlight is not possible. I could be proven wrong.

Interesting in this context was the discovery of hydrogen depletion as one gets close to the surface and the unexpected lower amount of acetylene there :

https://phys.org/news/2010-06-consuming-hydrogen-acetylene-titan.pdf

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20160006882/downloads/20160006882.pdf

Some alternative form of biological activity was suggested.

The H2 depletion towards the surface implies that life is at the surface or in the methane/ethane lakes. This seems somewhat unlikely. If there is [sparse] life in the subsurface ocean, how is it getting access to the organic material on the surface, separated from it by tens of km of water ice?

I would want to rule out physical or chemical reasons for any H2 depletion, rather than resorting to the life explanation. As the hydrogenation of organics, especially acetylene, is so exothermic, I would suspect some form of catalysis at the surface. Maybe that is testable by experiment in the lab. Titan is very cold on the surface. Any life processes would be very slow indeed, at least by terrestrial standards. Of course, it might be so slow that we might not recognize life even if we metaphorically trip over it.

Anyone have thoughts on possible ways hydrogenation might be accelerated at the surface?

What I remember reading -and I don’t know whether it’s true- it’s that, in ordinary conditions the hydrogen acetylene reaction is explosive/very energetic but, at Titan’s temperatures it was rather more similar to ordinary metabolic reactions.

Enzo, Titan is very dry and perhaps static electricity between particles at the atmosphere surface interface is the driver of the hydrogen and acetylene disappearance as more complex molecules are created.

As backdrop, per the Wikipedia entry for “Geology of Titan,” under “Cryovolcanism and mountains” the moon potentially has tectonic movement with subduction.

See also their main entry for “Titan,” under “Tectonics and cryovolcanism.”

My query is whether we can effectively rule out subduction as a mechanism for more or less consistently bringing enough organic material down below the ice to the internal ocean.

The article pretty much rules out episodic comet and meteor impact events as being sufficient to do so consistently in enough quantity.

And the article further refers to “localized concentrations,” but I didn’t see anything with term-search-assisted scanning speaking specifically to any related effect from possible subduction or tectonic dynamics generally.

Given the different materials and conditions involved on Titan in comparison to subduction on Earth, subduction on Titan perhaps could be a sufficiently dynamic process to regularly bring enough organic material ultimately to the internal ocean.

And it might be conceivable that with sufficient at-first localized (although subduction could extend along a line or lines of relatively considerable length) entry into solution in the ocean, the materials would propagate into the ocean more generally. And/or perhaps also precipitate more or less broadly onto the ocean floor, including near possible thermal vents from the core.

Perhaps, but it’s a (lay) thought anyway.

* * * * *

Interesting (to me) to see Professor of Astrobiology Charles S. Cockell of the University of Edinburgh in the author list for the article.

He has been fairly heavily involved over the past decade or so, including publishing, in considering questions regarding off-world systems of governance, including in particular on Mars.

“Small solar system.”

According Google AI, subduction does not happen on Titan due to it’s very thick ice is a rigid shell unlike Europa which has subduction. Consequently, there might not be any recycling of material from the surface.

That’s interesting, Geoffrey.

I don’t have much experience with the current state of AI, does it provide citation to specific scholarship? Or does it just give an answer to a coded term or query and refer generically to scientific consensus or some such?

I mean, the whole thing is just a passing lay thought, but if I were going to run down the rabbit hole, I would drill down into the source material cited on (the hardly infallible) Wikipedia underlying their references to tectonics and subduction on Titan. And then do the same with what AI is relying on. And try to thereby reconcile or resolve the differences in the two discussions, which of course could simply be me reading too much into what Wikipedia says in passing.

So, in that vein, does Google AI allow someone to examine the underpinnings of what it spins up as an answer to a coded term? In terms of citation to the specific human research upon which it relies?

I do find intriguing the possible strategies that life might take, and the resources that it might utilize, to gain a (microbial) “toe”hold in these markedly different environs around the solar system.

George, I use the paid versions of both Google Gemini and Chat GPT, mostly for research (I never have them write anything for me, which goes against my lifelong writerly instincts)! I usually run the same query by both to see if they agree, and always verify by running a separate Web search to see if I can verify what they give me. Both allow options for ‘deep research,’ meaning with citations on their findings, but both also stress that they make mistakes and shouldn’t be considered definitive. I find these AI tools helpful but they need to be approached with caution and double (or triple) checking. The technology is remarkable and transformative, but still in its infancy.

Thanks, Paul, it’s comforting then (to me) that there is that ‘deep research’ feature to allow drilling down into AI’s supporting citations.

Guess I really should start working with it if for no other reason so that I can see where others are coming from when they reply back to me referring to AI-generated content.

Which I imagine will be the case on multiple occasions once I get this oft-referenced proposed constitution for a Mars settlement finally out onto the aether.

So far, I’ve been less than impressed with AI at least circa early 2025, but admittedly my experience has been limited to (a) other folks replying to something that I’ve posted on X with a reference to a result to what they’ve coded (if I’m using the right terminology) on AI, and (b) those news summaries that Grok does on X.

In the first category, for example, an of course otherwise highly intelligent laser scientist might reply to something I’ve posted about about on X that relates to a fairly involved U.S. constitutional situation (“I don’t get many engagements on X for some reason,” lol) with some bit of supposed knowledge that they’ve derived from AI, along with a not very nice comment directed back at me. All in a situation where the coder and/or AI “didn’t know what they didn’t know” about either the underlying constitutional law substrate or the rather intricate political game theory situation based on that substrate that I was going on about.

So at least that sort of – use – of AI by an otherwise highly intelligent person hasn’t inspired much confidence in me.

But I guess any tool is only as good as the manner in which it is used.

Maybe they should add a disclaimer also that “just coding a term or two into AI won’t necessarily make you an expert in another field way, way, way outside your own field of expertise that you otherwise know nothing at all about.”

But that of course would tend to cut against those trendy commercials that they run on TV about the new AI on the cell phones they’re selling, where all the twenty-somethings speak with British accents – in the US ad – to make it sound all cooler, hip and trendier.

In the second category, Grok – which is distilling online posts on news items and has that same basic disclaimer to which you refer – direct exposure to that inspires even less confidence in AI circa April 2025.

The Grok summaries read like a college sophomore’s paper that’s due at 8:30 a.m. that is written as the sun is coming up after an allnighter where they’ve been staring at a blank page all night and they’re just writing – in terms of critical thought – blather that sounds like they’re saying something when they’re really not saying anything at least insightful. Just filler saying something somewhat related to the topic. Banal sophomore paper stuff. Because the one or two sentences that they’ve otherwise come up with approaching 8:30 aren’t enough to fill the page.

And, with Grok, that’s on a – one paragraph long – news item summary. Basically meaningless blather included within a one paragraph piece.

(But of course now college sophomores are instead using AI to fill out those papers, so I guess there’s a symmetry there.)

But you’ve persuaded me to finally break down and start working with it, as I say, to at least be familiar with what people are referring to in replies.

Maybe some day – after it attains that vaunted singularity (cue angel choir music) – it will transform laser scientists instantaneously into constitutional lawyers, and vice-versa.

(But, hey, if we then could dispense with lawyers, that would be a substantial advancement in Western civilization . . . .)

I’m like you, though, re: the writing. I was trained, even back before undergrad and law school, to drill down to original source material and do my own analysis – which in truth the writing itself is integral to – from that original source material back up.

I’m fairly sure that if I weren’t retired, they would be trying to get me to use AI to generate at least preliminary content “and then just clean it up a bit.” “Because it’s faster that way.”

But I’m just not wired to do it that way, as I believe that I both (usually) think and thus write better than the AI content that I’ve seen and would rather just do it right from the get go.

In that vein, the computerized legal research services already had added – well before AI became a thing – natural language searching as an alternative to terms-and-connector searching. I never used it, though, because with terms and connectors I knew exactly what I was getting and wasn’t relying on a (computer-generated rather than my own human) algorithm for the comprehensiveness of what I pulled up in the search. But I never got caught flatfooted because another lawyer found a case on point that I missed.

But, yes, I guess it’s (past) time for me to start working the new AI tech into the mix.

Hey, the lawyer may become an expert on Titanean tectonic dynamics, lol.

Interesting Titan is moving away from saturn.

https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/titan-migrating-away-saturn-100-times-faster-previously-predicted

Just wondering how big a space elevator or tube would work on Titan, seems to be easier than on the moon although the gravity well of saturn is quite large.

The environment around Saturn is hazardous due to its instability. The number of moons orbiting the planet has now increased to 274. Many of these newly discovered moons are approximately 3 kilometers in size and have unstable orbits.

Two moons were claimed to have been discovered by different astronomers but were never observed again. Both were said to orbit in the region between Titan and Hyperion.

Chiron was supposedly sighted by Hermann Goldschmidt in 1861 but has not been observed by anyone else since then. Themis was allegedly discovered by astronomer William Pickering in 1905, but, like Chiron, it has not been seen again. Despite this, Themis was included in various almanacs and astronomy books until the 1960s.

In 2022, scientists of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology proposed the hypothetical former moon Chrysalis, using data from the Cassini–Huygens mission. Chrysalis would have orbited between Titan and Iapetus, but its orbit would have gradually become more eccentric until it was torn apart by Saturn. 99% of its mass would have been absorbed by Saturn, while the remaining 1% would have formed Saturn’s rings.

Much like Jupiter, asteroids and comets occasionally come close to Saturn, with some rare cases of being captured into orbit around the planet. The comet P/2020 F1 (Leonard) is estimated to have made a close approach to Saturn on May 8, 1936, coming within 978000±65000 km (608000±40000 mi) of the planet. This distance was closer than Titan’s orbit around Saturn, and the comet had an orbital eccentricity of only 1.098±0.007. It is possible that the comet was temporarily orbiting Saturn before this encounter; however, due to the complexities of modeling non-gravitational forces, it remains uncertain whether it was actually a temporary satellite.

While other comets and asteroids may have briefly orbited Saturn in the past, none are currently known to do so.

Titan’s atmosphere might not be in equilibrium, and the lakes could indicate recent impacts. The gentle impacts from the moons orbiting between Titan and Hyperion may have played a significant role in creating Titan’s surface. This fascinating interaction indicates a complex and dynamic history, emphasizing the role of celestial mechanics in shaping the landscapes of one of the largest moons in our solar system.

@Michael, Micael Fidler

Karl Schroeder wrote a short story, “The Cold Convergence,” about a base on Titan. The denouement was that due to orbital dynamics, an electric conductor was generated from Saturn to Titan that channeled an immense electric charge that changed all the local simple hydrocarbons to complex organics of great value.

If only…