Rains have come to the equatorial regions of Titan, a vivid marker of the changing seasons on the distant Saturnian moon. A large storm system appeared in the equatorial regions in late September of last year as spring came to the low latitudes, and extensive clouds followed in October. When they dissipated, the Cassini orbiter was able to capture surface changes in a 500,000 square kilometer region along the southern boundary of the Belet dune field, along with smaller areas nearby, all of which had become darker. The likely cause: Methane rain.

Tony Del Genio (Goddard Institute for Space Sciences) is a member of the Cassini imaging team:

“These outbreaks may be the Titan equivalent of what creates Earth’s tropical rainforest climates,” says Del Genio, “even though the delayed reaction to the change of seasons and the apparently sudden shift is more reminiscent of Earth’s behavior over the tropical oceans than over tropical land areas.”

That’s an interesting take on these observations, because on Earth we find tropical bands of rain clouds year round in equatorial regions. On Titan, the evidence so far is telling us that extensive bands of clouds may occur in the tropics only during the equinoxes, bringing rain to what had been equatorial deserts. In fact, we’ve seen years of dry weather in the Titanian tropics, but now Cassini is showing us an area the size of Arizona and New Mexico combined that shows clear signs of saturation through a presumed methane rainfall that lasted several weeks.

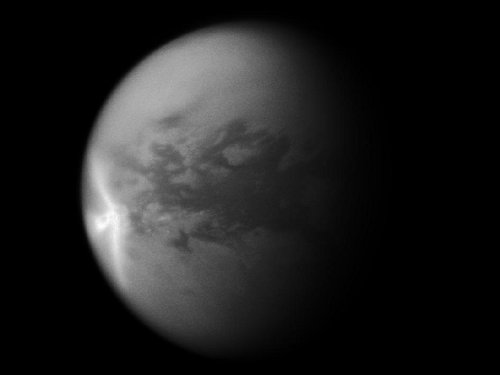

Image: A huge arrow-shaped storm blows across the equatorial region of Titan in this image from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, chronicling the seasonal weather changes on Saturn’s largest moon. This storm created large effects in the form of dark — likely wet — areas on the surface of the moon, visible in later images. After this storm dissipated, Cassini observed significant changes on Titan’s surface at the southern boundary of the dune field named Belet. The part of the storm that is visible here measures 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) in length east-to-west. The wings of the storm that trail off to the northwest and southwest from the easternmost point of the storm are each 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) long. Credit: NASA/JPL/SSI.

The changes in Titan’s weather over time are strikingly well defined. During the moon’s late southern summer back in 2004, major cloud systems were associated with its south polar region. The clouds seen in the 2010 imagery of the equatorial regions appeared one year after the August, 2009 equinox, when the Sun moved directly over the equator. The suggestion in this new work on Cassini data, which appears in Science, is that the global atmospheric circulation here is influenced both by the atmosphere and the surface, with the temperature of the surface responding more rapidly to changes in illumination than the thick atmosphere.

Thus we see Titan reacting to a change of seasons, though in delayed fashion, with an abrupt shift in cloud patterns that is reminiscent of what happens on Earth over tropical oceans rather than tropical land areas. Given these observations, the dry channels Cassini has seen in Titan’s low latitudes are likely caused by seasonal rainfall rather than being the remnants of a past, wetter era on the moon. Until this point in the Cassini mission, we had seen liquid hydrocarbons like methane and ethane only in the polar lakes of Titan, while the dunes of the equatorial regions were arid. Says Elizabeth Turtle (JHU/APL), lead author of the paper on this work:

“It’s amazing to be watching such familiar activity as rainstorms and seasonal changes in weather patterns on a distant, icy satellite. These observations are helping us to understand how Titan works as a system, as well as similar processes on our own planet.”

The paper is Turtle et al., “Rapid and Extensive Surface Changes Near Titan’s Equator: Evidence of April Showers,” Science Vol. 331, No. 6023 (18 March 2011), pp. 1393-1394 (abstract).

Titan’s equatorial deserts and polar methane lakes is similar to Earth after it has lost much of it’s oceans to space as the Sun brightens over the next two billion years or so. The loss of oceans is likely to be a gradual decline and without the extremes of Venus’s probable dehydration aeons ago, partly due to Earth’s carbon dioxide being locked up in deep rocks, partly due to the stately pace. Thus Titan now is Earth as it will be.

If it were not for the water = life paradigm, everyone would be exited by the prospects in this incredible world. Though there is room for more Earth like microbes deeper, it would be great to see speculations in newspapers, over what sort of catabolic (or, more challengingly, anabolic) biochemistry could be used in such a cold mixture of methane, how surface life might hide from, or overcome, the ultraviolet light, whether life is more likely in the lakes or land etc. This would highlight mystery of the strange unexpected chemistry at Titans surface, and what a amazing world this is even without native life. This would in turn provide a platform to point out the many ways that Titan will likely be part of our (far) future, including trivialities such as it might allow the dream of human powered flight. Icarus might inspire us yet again!

Instead I fear we are current boring the general public, who would rather see the money spent on area with better ‘publicity departments’ such as the funding alternative medicine.

It’s Raining on Titan

Illustration Credit & Copyright: David A. Hardy (AstroArt)

Explanation: It’s been raining on Titan. In fact, it’s likely been raining methane on Titan and that’s not an April Fools’ joke. The almost familiar scene depicted in this artist’s vision of the surface of Saturn’s largest moon looks across an eroding landscape into a stormy sky. That scenario is consistent with seasonal rain storms temporarily darkening Titan’s surface along the moon’s equatorial regions, as seen by instruments onboard the Cassini spacecraft. Of course on frigid Titan, with surface temperatures of about -290 degrees F (-180 degrees C), the cycle of evaporation, cloud formation, and rain involves liquid methane instead of water. Lightning could also be possible in Titan’s thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere.

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap110401.html

http://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/26662/

Like Europa, Titan May Have A Giant Subsurface Ocean

Titan’s orbit and rate of rotation indicate that a huge ocean may lie beneath its icy surface

kfc 04/18/2011

In the seven years Cassini has spent orbiting Saturn, the spacecraft has sent back mountains of data that has changed our view of the ringed planet and its moons. Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has been a particular focus of attention because of its dense, complex atmosphere, its weather and its lakes and oceans.

Now it looks as if Titan is even stranger still. The evidence comes from careful observations of Titan’s orbit and rotation. This indicates that Titan has an orbit similar to our Moon’s: it always presents the same face towards Saturn and its axis of rotation tilts by about 0.3 degrees.

Together, these data allow astronomers to work out Titan’s moment of inertia and this throws up something interesting. The numbers indicate that Titan’s moment of inertia can only be explained if it is a solid body that is denser near the surface than it is at its centre.

That’s just plain weird–unthinkable really, given what we know about how planets and moons form.

But there is another explanation, however: that Titan isn’t solid at all.

Today, Rose-Marie Baland and buddies at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, crunch some numbers to see whether a liquid model is compatible with the measured moment of inertia. “We assume the presence of a liquid water ocean beneath an ice shell and consider the gravitational and pressure torques arising between the different layers of the satellite,” they say.

Their conclusion is that Titan’s moment of inertia could well be explained by the presence of liquid ocean beneath an icy shell.

The chemistry of the ocean is an important factor in calculating its depth and how thickly it can be covered in ice. Baland and co assume that it must consist of water. That seems a curious assumption given that Titan’s atmosphere is packed full of methane and other hydrocarbons.

Astronomers have long known that methane is quickly broken down by sunlight. So Titan’s ought to have long since have disappeared…unless it is being refilled from an internal reservoir. A huge underground ocean of methane, perhaps?

A methane ocean would require Baland and co to look at their calculations again to see what the mechanical and thermodynamic relationship would be between methane ice and liquid. So there could be some interesting calculations ahead.

It’s also worth pointing out that there is another explanation for Titan’s strange moment of inertia. The calculations assume that the moon’s orbit is in a steady state but it’s also possible that Titan’s orbit is changing, perhaps because it has undergone a recent shift due to some large object passing nearby, a comet or asteroid, for example.

So although Baland and co’s analysis is good evidence that Titan has a subsurface ocean it is not quite a slam dunk. There’s more life in this problem yet.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1104.2741: Titan’s Obliquity As Evidence For A Subsurface Ocean?

A Cometary Case for Titan’s Atmosphere

by Jason Major on May 9, 2011

Ancient comets may have created Titan’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere

Titan is a fascinating world to planetary scientists. Although it’s a moon of Saturn it boasts an opaque atmosphere ten times thicker than Earth’s and a hydrologic cycle similar to our own – except with frigid liquid methane as the key component instead of water. Titan has even been called a living model of early Earth, even insofar as containing large amounts of nitrogen in its atmosphere much like our own.

Scientists have wondered at the source of Titan’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere, and now a team at the University of Tokyo has offered up an intriguing answer: It may have come from comets.

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/85496/a-cometary-case-for-titans-atmosphere/