The expansion of the universe ought to be slowing down — gravitational attraction working on the ordinary matter of the cosmos should see to that. So evidence produced during the last eight years that the universe’s expansion seems to be speeding up continues to confound astrophysicists. To explain it, a provocative notion has been introduced: two-thirds of the entire energy density of the universe consists of a new kind of energy. This ‘dark energy’ has the opposite effect of gravity, pushing away rather than attracting.

But is there such a thing as dark energy, or is it just a way to explain something so baffling that we have no other models to describe it?

“We don’t know,” comments Professor David Spergel of Princeton University. “It could be a whole new form of energy or the observational signature of the failure of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. Either way, its existence will have profound impact on our understanding of space and time. Our goal is to be able to distinguish the two cases.”

Spergel is referring to work he and Mustapha Ishak-Boushaki (also of Princeton) have presented to the Canadian Astronomical Society meeting in Montreal. They have come up with a technique for determining whether dark energy is indeed operational or whether (and the flip side is also startling) Einstein’s General Relativity breaks down at the largest scales.

Spergel is referring to work he and Mustapha Ishak-Boushaki (also of Princeton) have presented to the Canadian Astronomical Society meeting in Montreal. They have come up with a technique for determining whether dark energy is indeed operational or whether (and the flip side is also startling) Einstein’s General Relativity breaks down at the largest scales.

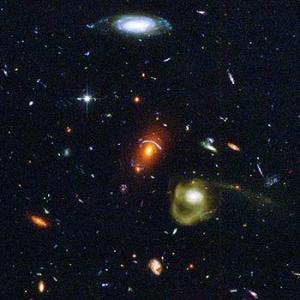

Image: Is it possible that a new form of energy accounts for cosmic expansion throughout the universe? Here is a typical patch of sky, as seen by Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys. The jumble of galaxies in this image, taken in September 2003, includes a yellow spiral whose arms have been stretched by a possible collision [lower right]; a young, blue galaxy [top] bursting with star birth; and several smaller, red galaxies. Credit: NASA, ESA, J. Blakeslee and H. Ford (Johns Hopkins University).

Consider, for example, how physics would be changed if this cosmic acceleration is showing us a new theory of gravity, perhaps one that can be explained by superstring theory with its numerous additional dimensions. That would be, if confirmed, an enormous breakthrough for superstring advocates, but we’re a long way from knowing for sure.

Ishak-Boushaki and team think there is a way to test for dark energy. From a Princeton press release available at the Canadian Astronomical Society site:

If the acceleration is due to Dark Energy then the expansion history of the universe should be consistent with the rate at which clusters of galaxies grow. Deviations from this consistency would be a signature of the breakdown of General Relativity at very large scales of the universe. The procedure proposed implements this idea by comparing the constraints obtained on Dark Energy from different cosmological probes and allows one to clearly identify any inconsistencies.

Centauri Dreams‘ take: What this means is that the Princeton team believes it can identify the signature of modified gravity models and separate it from those involving dark energy. Future experiments will be needed to distinguish the two, but the theoretical basis for making the call is now being developed.

For more on this, read Ishak-Boushaki’s “Probing decisive answers to dark energy questions from cosmic complementarity and lensing tomography” (2005), the preprint available here. The paper has been submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. From the abstract: “…the requirement for very ambitious and sophisticated surveys in order to achieve some of the constraints or to improve them suggests the need for new tests to probe the nature of dark energy in addition to constraining its equation of state.”

Spergel and Ishak-Boushaki also consider dark energy constraints in relation to the Terrestrial Planet Finder mission in a JPL white paper called “General Astrophysics and Comparative Planetology with the Terrestrial Planet Finder Missions,” based on a 2004 Princeton workshop and available here in Microsoft Word format.