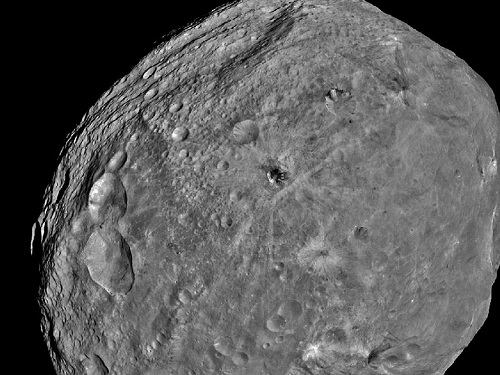

Considering the nature of the Dawn spacecraft’s slow, spiraling entry into orbit around Vesta, it’s a little unclear precisely when orbital insertion was, but NASA is pegging an approximate time of 0447 UTC on July 16. The event is leading to closer and better imagery all the time, the example below being the first full-frame image, taken from the spacecraft’s framing camera on July 24. Here we’re looking at the asteroid from a distance of 5200 kilometers, seeing for the first time the kind of surface detail that has long been hidden from even the most powerful telescopes.

Image: NASA’s Dawn spacecraft obtained this image of the giant asteroid Vesta with its framing camera on July 24, 2011. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

Dawn’s principal investigator Chris Russell (UCLA) likes what he sees:

“We have been calling Vesta the smallest terrestrial planet. The latest imagery provides much justification for our expectations. They show that a variety of processes were once at work on the surface of Vesta and provide extensive evidence for Vesta’s planetary aspirations.”

We’re going to be learning quite a lot about both Vesta and Ceres from coordinated work between the spacecraft’s radio transmitter and Earth-bound antennae, which will be used to monitor signals from Dawn to detect variations in the asteroids’ gravity fields. The intent is to learn more about the interior structure of the two objects. We’ll also use Dawn’s visible and infrared mapping spectrometer to measure the surface mineralogy of both asteroids. Dawn’s first of four intensive science orbits of Vesta will begin on August 11 at an altitude of 2700 kilometers.

A spectacular view of the rotating Vesta is offered in the following video:

Image: In this movie, strung together from a series of images provided by the framing camera on NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, we see a full rotation of Vesta, which occurs over the course of roughly five hours. These images were obtained on July 24, 2011, from a distance of about 3,200 miles (5,200 kilometers).

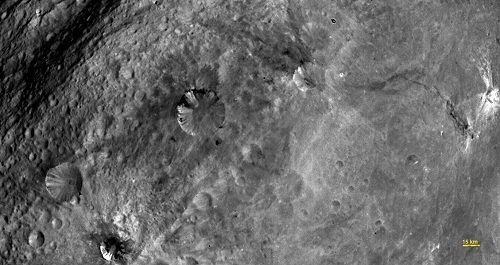

And let’s close with a closeup of craters in the southern equatorial region:

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

Beautiful.

I wonder what the surface escape velocity is?

Can human being jump off it?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4_Vesta

Oh, 0.35km/s, not even close. Well, I think Vesta is not as small as I thought. :-)

Parker

Pray for JWST

The rotation video is fascinating. A lot of really complicated surface features revealed there. I’m wondering about those parallel striations running along the equator — what could’ve made those?

I am speechless. The incredible resolution of surface details is remarkable, to say the least. I, too, am curious about the striations seen in the video. Paul, once again, thanks for sharing this marvel with us all. you’re awesome!

Apart from the stripes, Vesta doesn’t look much different from the usual cratered potatoes we have seen since Galileo flew by Gaspra.

Ceres will hopefully be more interesting with some surface ice : a Mars/Europa

hybrid ?

To me, it looks like–but I’m happy to be wrong–that the grooves result from glancing blows, where the asteroid has been side-swiped by smallish objects.

The best part? All of the images we’ve seen so far are from essentially an engineering and navigation instrument, the stuff we’ll get from Dawn’s state of the art instruments will probably blow us away.

“Apart from the stripes, Vesta doesn’t look much different from the usual cratered potatoes we have seen since Galileo flew by Gaspra.”

Not in black-and-white, but I’m wondering if we’ll be getting any color images. Vesta has a differentiated geology like a planet, so I’m hoping some of the craters are deep enough to expose inner layers. In fact, I’d been led to believe that the big bump on the southern hemisphere was the central bulge of a crater so big it flattened out the whole hemisphere, or at least that’s been the prevailing theory. I’d been thinking maybe that crater would’ve exposed some of the inner layers of the protoplanet. But it doesn’t really look like there’s a crater there. Maybe it’s just eroded largely away, but maybe the bulge and the flattening have some other explanation.