Talking about Mason Peck’s notions of ‘swarm’ spacecraft — probes on a chip that might reach interstellar speeds — I’m inescapably drawn to the other end of the spectrum. A ‘worldship’ is a mighty creation that may mass in the millions of tons, a kilometer (or more) long vehicle that moves at a small fraction of the speed of light but can accommodate thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of inhabitants. What promises to be the first scientific conference devoted solely to worldships is about to take place on Lambeth Road in London at the headquarters of the British Interplanetary Society. The day-long conference gets down to business on the morning of August 17. This BIS page offers a draft of the program.

As the BIS has done in the past, all presentations from the conference will be written up in a special issue of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, where much of the early speculation on worldships has taken place. Several of the Project Icarus team will be presenting papers and I notice that solar sail expert Gregory Matloff, one of the analysts of worldship ideas in the pages of JBIS back in the 1980s, will be represented with a paper on sail options for such a mission. Beyond that, the conference aims, in the words of its organizers, “to reinvigorate thinking on this topic and to promote new ideas.” It will “focus on the concepts, cause, cost, construction and engineering feasibility as well as sociological issues associated with the human crew.”

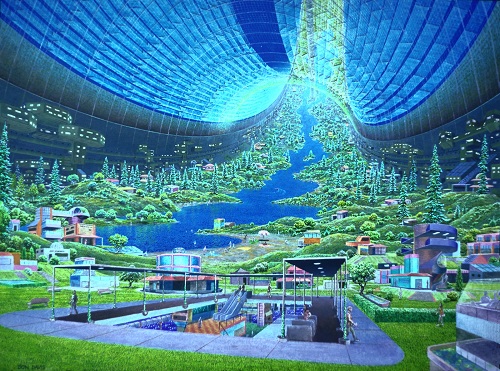

Image: A worldship may eventually take shape by drawing on the design of space habitats built closer to home. Credit: Don Davis.

Those of you who are familiar with The Starflight Handbook, Matloff’s seminal work on interstellar concepts (John Wiley & Sons, 1989) may recall a write-up on a mission called Sark-1, described as a ‘solar sail interstellar ark’ and named in honor not only of the sailing vessel Cutty Sark but the whiskey that now bears its image. The latter reference is a nod to the fact that a generous store of spirits would not go amiss for those involved in a journey scheduled to last at least a thousand years.

The Sark-1 would be, in comparison to some of the behemoth worldship concepts that have followed, a relatively small vessel, carrying a ‘modest’ crew of 1000 to the Alpha Centauri system. Working with Eugene Mallove, Matloff went on to allot roughly 40 square yards of living space for each person, lodged within a toroidal cabin structure that would weigh 2500 metric tons on the Earth’s surface. Now figure 1000 tons of atmosphere, supplies and power plant adding up to 2000 tons, giving you a basic 5500-ton space colony minus the essential sail. The authors then round the number up to 10,000 tons, thus providing for supplies needed upon arrival.

You make a lot of assumptions when trying to design something that only futuristic technology can deliver. Matloff and Mallove divide the colony into a fleet of six starships, each towed by a circular sail 380 kilometers in diameter, and assume micro-fine filaments of diamond for support cables. For propulsion, a close solar pass would involve an initial perihelion velocity of 0.0014 c, making travel time to Alpha Centauri about 1350 years. The sail — folded and stowed during the cruise phase — would be redeployed upon approach to the Centauri stars, electrically charged and used for deceleration. What the authors say next meshes nicely with the upcoming conference:

Missions by solar sail starship habitats lasting millennia may never be attractive to terrestrials. However, long-term residents of space colonies in the solar system or members of other spacefaring civilizations in the galaxy may not feel equally constrained. Furthermore, as we have seen, there may be undiscovered stars much closer than Alpha Centauri, so we may eventually discover destinations only a few centuries away via inhabited solar sail starships. So in addition to research on solar sail materials, starship dynamics, and logistics, it is not too soon to undertake sociological studies of the problems of maintaining interstellar colonies. Whether clipper ships of the galaxy will ply the interstellar ocean in the twenty-first century, as white-sailed Yankee clippers once did in the nineteenth, is a question our children may be able to answer.

Moving well beyond Sark-1, a true worldship would need to approximate a terrestrial environment inside a far larger vessel. The idea, after all, is to deliver a population of colonists who are not only equipped for the job but sane enough to accomplish it. That may well require structures on the scale of an O’Neill habitat, gigantic vessels housing many of the amenities we take for granted on a planetary surface — parks, lakes, farms — with ample room for living and carrying out a rewarding life as the interminable journey progresses. The typical Earth-dweller isn’t designed for such a mission, but long-term colony structures in the Solar System may one day breed a population for which living on a planetary surface is something of an anomaly. Will the descendants of this kind of habitat head out to become our first interstellar colonists?

For more, see Matloff and Ubell, “Worldships: Prospects for Non-nuclear Propulsion and Power Sources,” JBIS 38 (June 1985), pp. 253-261. See also Matloff and Mallove, “The First Interstellar Colonization Mission,” JBIS 33 (March, 1980), pp. 84-88.

“a generous store of spirits would not go amiss for those involved in a journey scheduled to last at least a thousand years.”

That’s thinking at the wrong scale. You don’t need a store of spirits, you need a distillery industry.

And I think the analogy of a clipper ship is wrong. Those voyages were long, but the travelers expected to see the destination. I think nomadic people are a better analogy for the intermediate generations that will spend their entire lives on the ship. They travel as a way of life, not because they are trying to get to a destination.

SF author Charles Stross has asked the question – how big does the population need to be to sustain a technological colony on another world. The answer seems to be very large indeed, the size of a country.

One has to ask what advantages a worldship would offer its inhabitants to disembark at another star? It is one thing to maintain a comfortable life in a space colony withing the solar system, but quite another in deep space without any prospect of trade or help. If life can be comfortably sustained inside it for over 1000 years, why would anyone risk life on an untamed/unterraformed the target world?

Unless technological development stalls out, any slow ship is going to find itself overtaken by later, faster ships.

What is the compelling reason to make such a journey to another star? Intolerable oppression? Escape from some danger?

Completely off-topic (or is it?), but, Paul, if I am not mistaken you started (your first post on) this website 7 years ago today: 4 august 2004. Am I right or not? Not too far off I guess.

Anyway, a wholehearted congratulations to you, Paul Gilster, for a very unique and fascinating website on an equally fascinating topic. It has become one of my two favorite sites, together with Brian Wang’s Next Big Future.

Lots of good luck and success to you and keep up the good work!

Very kind of you, Ronald, and you’re right, it was seven years ago today. I thank you as well for having been a part of this site from the beginning.

Bob Steinke points out quite correctly that a distillery industry is necessary, rather than a large supply of… anything, really – and adds that travel will be a way of life for the inhabitants of a generation ship. I agree strongly and I’d like to elaborate by pointing out that for these people, after a few hundred or even a thousand years, any planetary bodies discovered in the destination system will be of little interest. They will not be colonists.

They will have already existed for generations in a self-sufficient mobile environment. They may gather some resources in the destination system, but probably from asteroids and comets. They will avoid dealing with any deep gravity wells. They may linger in the new system awhile; optimally, they will linger long enough to construct a second generation ship similar to the first, and populate it. But then they will move on.

By the time their plodding 400 kps gets them to their destination solar system, it would already be swarming with habitats built by the descendents of those who went in much smaller and faster ships, hibernating at 0.1c.

For the same resources required to build and fly a worldship for a millenium, a society could send swarms of smaller, faster ships on a century-long hibernation-voyage with minimal consumption during the journey. Moreover, only a society comprising thousands of huge asteroidal habitats could afford interstellar spacecraft anyway, so they’d already be living in worldships. Why traipse across the Void for millenia when the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud are so close?

It might be a different story for matter-poor systems such as white dwarfs, which would not attract high-speed settlers. Such dregs would be the only destinations a worldship could select without worrying about arriving late to the party, rather like a hermit rowing his boat to an unihabited island so small it would only support one person. He knows that it will still be empty when he finally gets there, since all the clipper-ship traffic is going to desirable places.

The ‘land rush’ will target Epsilon Eridani, Tau Ceti, and Epsilon Indi, and then race further outward towards other matter-rich systems. Meanwhile, the worldships can have the nova-blasted white dwarfs of Sirius, Procyon, and van Maan’s star, dead-end systems with low growth-prospects: perfect destinations for advocates of zero-population growth to set up the equivalent of isolated monasteries.

As O’Neill first pointed out, we have to cast off our planetocentric bias and think like a spacer. Planets are a hassle to mine, but asteroids are easy.

Let’s also remember that the value of a world with macroscopic life is not colonization but biological research. Only sterile robots would be allowed to land and bring back precious samples and send back webcam images. Landings by people, let alone colonization attempts, would be regarded with enough horror to be a casus belli. Terraformed planets, however, would be nice vacation-resorts but the trillions of people living in space habitats who paid for it would not be keen on a few billion people hogging such a planet, especially considering the millenia that Terraforming requires. By that time the Dyson Swarm would be full.

Dyson swarms? So you want to launch vast quantities of mass out of the plane of the system then have to manage collision avoidance – hope you supplied all the zillions of satellites with enough propellant! Then you’ve got the question of maintaining a sustainable environment on the various habitats…

Seems to me these kind of mega-engineering problems make for fairly interesting physics thought-experiments but don’t really make much sense as a practical suggestion.

Morgan Freeman’s, Through the Wormhole, had an interesting episode on 7/27, ‘Can We Live Forever’. The genetic research was particularly encouraging. By the time we should be capable of building a world ship, we may live long enough to survive or get it down to a few generations.. I must admit, the long trip may still lead to mass insanity, and they still may not want to trade a comfy world ship for a dangerous planet. But, wow.

Diversity being what it is, I’m sure some spacers would want to get out and colonize a planet while some would want to stay in their ship and move on. Some would volunteer for a world ship with or w/o tech progress or hibernation. Technology isn’t that predictable.

Even a “hibernation ship” would probably have awake humans onboard for maintenance and supervision. Which would begin to combine the ideas of world ships and hibernation ships. (xx% of crew awake at any time, in shifts, fixing people, the ship, systems etc.) Unless I’m wrong about having awake humans onboard. Thoughts?

I thought the world ship concept was considered non-credible. Robert Forward made the point at a conference I attended in the late 80’s that one simply does not go to the stars until the travel time can be reduced to 50 years or so. Until then, you stay home and work on better propulsion technology.

Assuming that world-ships are valid, it seems to me that they would incorporate all of the technology and processes that a O’niell space colony would have. The bio-meme technology would have to be better than a conventional O’niell habitat. If you run out of a particular resource, you can always find another asteroid or comet to mine. This is not an option in interstellar space. It seems to me that world-ships would only be built if no faster propulsion technology is possible and we have to crawl our way to the stars. All of this suggests that world ships would be built by those who already have lived in space colonies for several centuries and that the world ships would simply be improved versions of such habitats.

I think Charles Stross is wrong about the number of people necessary to maintain technological civilization. I think this could be done with, say, around a 100,000 people. Also, the industrial processes necessary to settle another star system will be the same technology necessary for settlement of our own solar system. Mining, refining, and other process technologies can be scaled down to smaller systems that can be built and run by a small number of people. Automation will help as well. Making robots that can make more robots based on modular components will also make it possible for a small number of people to recreate and industrial infrastructure.

The biggest impediment is semiconductors. Advanced semiconductor devices are made in complex multi-billion dollar fabs that are the size of football fields. Some kind of self-assembly process technology will likely be developed in the next 20-30 years that will make molecular electronics willout the need for such complex expensive fabs. Manufacture of airplanes and cars can be improved in a similar manner.

Paul,

The space colony illustration above is not by Syd Mead, I painted it for NASA in 1975. As in the case of all NASA commissioned art, it is in the Public Domain. It can be downloaded (in better quality) here:

http://www.donaldedavis.com/PARTS/allyours.html

Don Davis

We should not forget how very many posit that the impossibility of interstellar travel is the answer to the Fermi paradox. If there is any shadow of truth behind this line of argument then it could only apply to faster travel and generation ships would turn out to be the only way to go.

Actually generation-ship inhabitants might be expected to have been strongly selected for high intelligence, and to have a community-wide obsession with breakthroughs that might lead to their descendants coming upon their destinations second. Wouldn’t it be ironic if one of them made the long sort after breakthrough that made faster forms of travel practical!

I hope this conference can come up with a cost and schedule for a viable artificial gravity worldship that the international community can sign up for. But I highly doubt it given the world economy, and I don’t see things getting better in the near future. Grandiose plans that go nowhere are a colossal waste of time.

However, I see worldships as the best insurance policy, even vital, for the survival of humanity so we must forge ahead with the next best option, zero-G ships. I know I harp on this but I see no other immediate path. For those of you who don’t think anyone will sign up to be the first zero-G pioneers, I can think of one candidate. Stephen Hawking should love to escape the gravity that seems to be crushing him further into his wheelchair. In zero-G you can fly.

We already have the pieces to bootstrap such a ship. The ISS, Bigelow’s modules and the private sector vehicles coming on line. This ship should remain in close earth orbit because of the support it will require until it becomes self sustaining. I discount the argument that earth like environments are needed since so many people today are almost exclusively lifelong apartment dwellers. At the very least we can conduct space environmental science in this island in the sky.

I am so hard over on this issue that I am seriously considering leaving all my worldly possessions to SpaceX; even though I think their rocket/capsule technology is out-dated and Mars colonization is the wrong approach because it is too far away to be supported. Until I can find a more committed person seriously working for an off world population as soon as possible, Elon Musk is my man.

Don Davis writes:

Don, sincere apologies — I’ve fixed the mistake in the attribution above.

Paul, in the first paragraph you state:

“A ‘worldship’ is a mighty creation that may mass in the millions of tons, a kilometer (or more) long vehicle that moves at a small fraction of the speed of light but can accommodate thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of inhabitants. ”

What bothers me is the size. I cannot immagine 1000’s or 100,000’s of people on a millenial journey tucked inside a vessel only 1 Kilometer long. I would hope the vessle would much much larger than that — or perhaps several vessels 1 Km long that housed 100’s of people. I think on a voyage like that, people would get crazy without some open space, elbow room, etc. At least the 1st generation of voyagers would need the room… without having open space in their experiece, the children would become accustomed to cramped quarters and the journey might be easier for them. But then, what happens when the destination is reached?? I can see that generation of travelers having problems with open space and they might prefer living in the ship. Or maybe it would influence the way they build their cities and homes. And how about their social abilities – how do they get along with eachother? I can see some people becoming complete isolationists while others might become fairly aggressive. They might form a society divided into factions based upon the sociability preferences of the individuals. Would this provide the kind of individuals who will build a colony, continue the technological developments and all other things of the culture that sent them off in the first place? I rather suspect Interstellar Bill has it right – the Millenials would arrive at their destination to find a world inhabited by the progeny of those who sent the first generation off. I remember reading a story about that once… a long time ago.

Anyway…

I believe we all agree that world ships have a long way to go before we actually are able to do this but not just the technology, but the ideas that form the basis of the technology. When we get some novel, ideas that don’t involve millenial ETA’s, I think this idea will be more likely to take off.

I love this idea, but we need to get near Kardashev II before it makes any sense. I agree with Mark Presco; how about more conferences focused on near future space goals instead of these far future science fiction speculations? Maybe we need to get our asses out of low earth orbit again before we start designing interstellar world-ships?

Also, what about hollow, spinning asteroid ships? That’s still a huge challenge, but at least you’re out of gravity wells, have good shielding and can get most of your resources in space. Now that we’re beginning explore the asteroids, how about plans for colonizing them? This seems like something we could actually do in next 50-100 years.

The Island of Manhattan is only a few kilometers in size, and holds 2 million people. Many of these do not care much for open spaces, and hardly ever leave the city (one Isaac Asimov, in particular, has professed to this). I think the capacity of people to adapt and preserve their sanity under extraordinary conditions is much underestimated by some of the commenters above.

About how many people it takes to maintain a technological society, Stross would have been right before the recent development of information technology and automation. Advanced automation will in the future drastically reduce the number of people needed until it reaches zero.

Kurt mentions semiconductors. True, huge factories are used to make them, but those are optimized for high volume production. A much smaller workshop with a few versatile machines can also make chips. Too few of them to supply all of humanity with iPads, but more than enough to keep those same machines supplied with replacements as their chips wear out, which is what counts. I am not familiar with the semiconductor industry, but I suggest looking at a research lab instead of a fabrication plant for the proper example of scale. Also, you do not need the latest and greatest 25 nanometer technology. Micrometers is enough, and much, much easier.

I belive at the leading edge of thought one comes to realize that the most significant and important goal for humanity is space colonization, I am happy to see you are reporting on this.

This is a fascinating blog that i try to share with everyone.

Thank-you!

It might be a better idea to set up self-contained “island” settlements along the way, so that the journey could be made in stages. This would take into account the possibility of superseding technology.

Also I think the colonization of comets should be more thoroughly investigated. The long process of station construction would be made more manageable if we work with objects already available. Imagine a colonized comet with an extreme orbit coming around every thousand years.

Eniac: “I think the capacity of people to adapt and preserve their sanity under extraordinary conditions is much underestimated by some of the commenters above.”

All it takes is one intelligent and delusional person with a devastating plan who believes everyone is better off dead than being a sardine in a can. I expect that internal security will be an obsession on a world ship. Totalitarianism anyone?

While no Man may be an island, tribes of Men (e.g. Sentinelese) have thrived on them for thousands of years in isolation.

Tribes of Men eh? Presumably no women allowed?[/snark]

Of course, these islands benefitted from the atmosphere and ecology of an entire planet. Air, fish, birds etc. were not confined to the island…

And Rapa Nui didn’t turn out particularly well did it…

@Ron S. Or lots of fail safes and a Heinleinian tendency to throw transgressors out the airlock.

Andy, presumably resources wouldn’t be an issue on this “island” either, nor would there be a scarcity of women, whom I would argue (some might say naïvely) in contrast to most, if not all, Earth tribes of Men, should hold an equal role in, and responsibility for, providing leadership.

Alex, toy problems can have fail safes, but they don’t exist in the real world. You’re welcome to show me a counter-example to prove me wrong.

As to the airlock solution, note my reference to security and totalitarianism. So you seem to agree. Nice place to live your life, eh?

andy… some people have a taste for stone monoliths.

Kurt9: the worldship concept is credible, despite what Forward says, because a planetary system is a huge resource, and at typical industrial growth rates of 1 to 2 per cent per annum it would take 1000 to 2000 years to develop the system. Therefore arriving late by up to a millennium or so is not a problem, if the point is to colonise the system. However it is a problem if the goal is to arrive first, obviously.

A lot depends on whether high-energy propulsion systems become feasible, and this is impossible to predict. In one future scenario, fusion or antimatter rockets or spacewarp drives are like controlled fusion today: the development costs rise to infinity before a practical piece of hardware is built. Alternatively, there may be a breakthrough in one or more of these analogous to the appearance of say the internal combustion engine or the jet engine, and uprated versions of these engines could get us to the stars within a couple of centuries. We just don’t know how the future will pan out yet.

Stephen

@ Ron S

I do agree with you. Next time I will try to telegraph it more effectively. British ironic humor doesn’t translate well in text. :)

World-ships seem better as the habitats of cosmic nomads than for colonists of *ick* planets.

———-

I cannot imagine 1000?s or 100,000?s of people on a millenial journey tucked inside a vessel only 1 Kilometer long. I would hope the vessel would much much larger than that — or perhaps several vessels 1 Km long that housed 100?s of people. I think on a voyage like that, people would get crazy without some open space, elbow room, etc.

———

Seems quite roomy to me, depending on how much of that space is actually used. Assume a ship 300m in diameter by 1600m(1km) long. Excluding the ends (which might be too important for general use) that would be roughly 1,508,000 sq meters, or 59 percent of 1 sq mile, for surface area. There are a number of cities with populations over 100,000 per sq mile. 10,000 people with 60 sq meters of living space each living in complexes 10 stories tall would only require 60,000 sq meters, or 4 percent, of that area to be devoted to dwellings. Industry and food production could be located at the core of the ship so the entirety of that 1,508,000 sq meters could be devoted to the living area and include parks and such.

But that is just one such design. The ship could be composed of cylinders, one inside of each other. Assume 10 such each occupying 10 meters of the ships diameter, again with the core of the ship devoted to industry and food production. The living space is now 12,566,000 sq meters, or 4.9 sq miles.

Such a ship could easily carry 50,000 people without it getting crowded and have a ton of wide open spaces (except for the sky/ceiling which could be designed to look like a natural sky). 100,000 wouldn’t be a stretch.

Security is already an obsession in the US, to the point where it will be indistinguishable from totalitarianism if “improved” any further. On a ship, at least, it is much easier to control the flow of weapons and people than in the wide open cities of Earth, so a given measure of security would be easier to achieve, with less drastic measures.

Any millenial journey would have to be a fleet of ships, with the loss of one or two to whatever causes accounted for as an acceptable risk.

I don’t think there will ever be precious space and resources wasted for parks and lakes, that is just blue-eyed romanticism. People will have to adapt to virtual reality for recreation, as envisioned in Star Trek (think holodeck). Many of us are already more than half-way there, with our video-games, entertainment and fitness centers. If you really want “open space”, there is always the observation deck….

I am glad to see the thinking of a worldship / multigenerational starship getting away from an Earthlike exoplanet being the ultimate goal. With an entire galaxy of 400 billion star systems to choose from, heading from one Earth to another seems very limited in the grand thinking department. Why even go into space if we just want a copy of our planet, not to mention what has already been said about such a world probably not being empty, even if there are no “higher” life forms.

There is another potential answer to the Fermi Paradox: Anyone exploring the galaxy treats planets and other natural celestial bodies as places to get resources and sightsee, not live upon. They much prefer their luxury space liners.