Projects that take more than a single generation to complete — the Ultimate Project that would build a multi-generational starship is a classic example — keep the issue of long-term thinking bubbling in these pages. The immense distances to the stars almost force the issue upon us. I’m reminded of something Hoppy Price told me at JPL five years ago. I was researching my Centauri Dreams book and we had been discussing the idea that scientists should see the end of the projects they start.

“Robert Forward talked about getting there in fifty years or less, a time scale that seemed to make sense because it would equal the possible lifetime involvement of a researcher,” Price said. “What may be more reasonable is to take a little more time. Because we’re also working on the beginnings of a program to build very long lifetime electronics, systems that can operate for up to two hundred years. If you let yourself take two, even three hundred years to get there, the problem of propulsion becomes a bit easier. We as a culture may have to start thinking in terms like that. The average worker on a medieval cathedral didn’t live to see it completed. My view is that the first time we send something to Alpha Centauri, it will probably take hundreds of years to get there.”

As NASA’s lead investigator on solar sails, Price had been thinking about these things for some time before I walked into his office that day. Note the medieval cathedral he mentions, a frequent reference in such discussions (and see the comments to yesterday’s story for more). It may seem hard to believe, but long-term missions to Alpha Centauri aren’t hugely beyond today’s technologies. Although the basics of the Innovative Interstellar Explorer design have changed, Ralph McNutt (Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory) has studied systems that could take a probe to 1000 AU in less than fifty years. Now imagine that system ramped up to move ten times faster. The resultant craft would reach Alpha Centauri in about 1400 years.

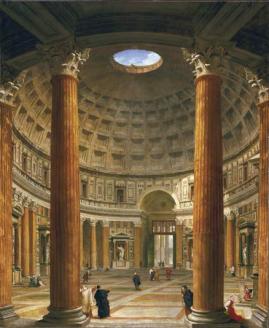

1400 years. Buildings on Earth — the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the Pantheon in Rome — have been maintained for longer than that.

Image: An 18th Century view of the Pantheon by Italian artist Giovanni Paolo Pannini. If we can keep a building alive for over a millennium, can we do the same with a spacecraft?

We all want to see faster propulsion technologies (this is why the Tau Zero Foundation is trying to support ongoing research through philanthropy). But it’s interesting to see how we cope with long-term solutions to things. In the business world as opposed to the ecclesiastical realm of cathedrals, we have abundant examples of companies that have been handed down for centuries within the same family. Construction firm Kongo Gumi, for example, was founded in Osaka in 578, and ended business activity only last year, being operated by the 40th generation of the family involved. The Buddhist Shitennoji Temple and many other well known buildings in Japanese history owe much to this ancient firm.

And here’s another, also from Japan. Hoshi Ryokan is an innkeeping company founded in Komatsu in 718 and now operated by the family’s 46th generation. If you’re ever in Komatsu, you can go to a hotel that has been operated on the site ever since. Nor do we have to stay in Japan. Fonderia Pontificia Marinelli has been making bells in Agnore, Italy since the year 1000, while the firm of Richard de Bas, founded in 1326, continues to make paper in Amvert d’Auvergne, providing its products for the likes of Braque and Picasso. I’m drawing this list from The 100 Oldest Companies in the World (thanks to Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation for the pointer) and continuing to muse on our species’ ability to work and preserve.

Image: Japan’s Ise Shrine (Mie prefecture, Japan). The wooden temple complex has been rebuilt every twenty years for the last thousand, a classic example of long-term effort in maintaining a structure.

We live in a world of immediate satisfaction, snapping up luxury goods with every tick of the eighteen month cycle of the digital revolution, but it’s good to step back and reflect on the things that last. Ultimately, exploration is less about the individual and more about the species, as is scientific discovery itself. And I would wager that if we do fail to find a means for shortening the interstellar trip in the next century or two, we’ll still make the journey. Maybe with generation ships, maybe with robotics, and using who knows which currently feasible system of propulsion. Let’s keep thinking about innovative technologies, but let’s remember that in the broader scheme, our species has shown it can go for the long haul.

When it comes to going to Alpha Centauri or another nearby star, I don’t think sending a starship that will take centuries or more to arrive makes any sense. It doesn’t make sense because long before the ship arrives, humans will very likely be able to build much faster vehicles and overtake it. Suppose we dispatch something that will reach the Centauri system in 1400 years. Now suppose that by 2150, we can build a spaceship that can reach 50% of the speed of light. Why would scientists in 2150, who could easily build a new starship and get the data in their lifetimes (within 20 years, in fact) want to forego doing this simply to let the original probe get there first? If they do this not only they, but their descendants for centuries to come, won’t get to know about the Centauri system. It would be like continuing to rely on technology from Christopher Columbus’ time today.

And from what I’ve read about interstellar travel, there’s a good chance that if we were determined enough right now, we could send a ship to Alpha Centauri in a matter of decades, not centuries. There is a proposal, which seems currently doable, to use 2 million tons of americium to reach 6% of the speed of light (or 12% with a two-stage rocket). There is also, of course, the Orion starship. Even the less optimistic estimates for Orion’s possible speed suggest that it could reach about 3% of the speed of light–enough to reach Alpha Centauri in 130-140 years. While this means that the people who launched the ship on its way wouldn’t live to see the results, it’s still much more reasonable than waiting 1400 years. It would be like getting data today from a ship that had set out during the Civil War, as opposed to one that was launched in 600 A.D. That’s quite a difference!

An interstellar voyage lasting centuries or more would only make sense if the star in question was hundreds or thousands of light years away. This is because there is no known way of surpassing the speed of light, and no reason to think one will be found in the foreseeable future (although there’s always the possibility of wormholes and such). So unless faster-than-light travel is found, humans on earth will have to wait centuries or longer for the results from stars at these distances no matter what we do.

I think our next goal should be a trip to the Sol focal point which is around 550 AU. If our spaceship can’t reach this distance in less than 10 years, then it’s pointless to think about travel to the nearest star.

It doesn’t matter whether this method of interstellar travel is eventually used or not. As a thought exercise alone it has inherent worth in that it keeps the debate alive and fresh, and new ideas are put to the forefront.

Without the generation ship concept there would be no Dyson Spheres, Bank’s Orbitals, O’Neill Colonies or Niven Ringworlds.

Other long term projects that might get built.

Well I’m not going to rehash arguments over cathedrals and projects taking many lifetimes to complete, so I’d like to try taking a fresh perspective on the issue and see what people think.

Let’s take a step back for a moment and look solely about the problem of establishing a colony on Mars. Virtually everyone who’s cared to think about this subject probably believes that one day we will establish a permanent settlement on Mars, however I’m sure they are realistic enough to know that it almost certainly won’t be in within their lifetime.

But the key thing to remember is that while establishing a colony on Mars may be the ultimate goal, there are many, many things that have to happen first, each of which would be an accomplishment that people working on those projects can be justly proud of having worked on, perhaps for most of their career. For example, many missions like the Mars Rovers and Mars Global Surveyor can be a couple of decades from conception to termination and while they don’t get us to Mars by themselves, the people working on those projects for half their careers get to see them come to fruition and no doubt find that immensely rewarding.

This will happen again and again in the future as sample return missions are done, then the first manned missions are carried out. Each, while part of a much longer term (perhaps more nebulous) goal, is a worthy and fulfilling goal in its own right.

In reality there really is no “grand design” or “ultimate project” to establish a Mars colony. Indeed there really isn’t much of one for just getting us to Mars. But the goals and outline have been mapped out enough that we pretty much know what steps we need to take in order to get us there, and people will willingly work on just one or two of those steps their whole careers not because of some overarching feeling that they are part of a multigenerational effort (although there may be a vague sense of that) but because they want to be part of projects they can help shepherd through to a successful conclusion.

Thus it will be for interstellar travel. Yes, it may take centuries to before we set foot in another solar system, but that doesn’t mean we need to have a centuries-long project for us all to work on to achieve that goal. Exoplanet hunters don’t spend their days wistfully dreaming of their distant descendants setting foot on an alien world, they caught up in the race to detect the first Earth-twin extrasolar planet. Those working on the Terrestrial Planet Finder aren’t driven by thoughts of their great-grandchildren setting off on an interstellar voyage, they are excited by the prospect of working on a project that might produce the first detailed images of planets around other systems.

And so comparisons with the building of a cathedral are not terribly apt. While no doubt workers then got a kick out of completing the nave, or transept, or whatever they happened to be working on, accomplishing those goals really didn’t amount to much since until the building was complete, it was of little use. That’s just not true with the roadmap to the stars. Every step of the way serves to improve our technology or increase our knowledge of the Universe in many different and meaningful ways.

There is some merit in putting some thought into what, ultimately, it is we’re trying to achieve and there is certainly merit in creating a framework that encourages the brainstorming about issues and ideas way down the line. But trying to corral all that into something like the “Ultimate Project” which, like it or not, switches all the focus onto a design and process that doesn’t comport with the way we do things. just seems to be missing the whole point.

By the way, is it really still necessary to moderate every comment posted on this blog? As a blog owner myself, I understand the pitfalls of having an open comment system, but using a combination of spam filter like Akismet and perhaps moderating the first post from a new commenter, it’s really not that likely you’re going to get much objectionable material posted in the comments.

Just askin’.

Hi Paul;

Excellent and inspirational article by the way! I think we have the moral imperative to go it for the haul.

Even if FTL travel proves impossible, although I certainly hope in the possibility of the development of practical FTL travel such as warp drives, wormhole travel, and the like, we still perhaps have at least one good thing among perhaps many going for us, and that is the possible existence of the Higgs Fields and associated bosons.

As we are already aware, the Standard Model proposes the existence of the Higgs Field as the mechanism by which massive particles have mass-based inertia and a finite or non-zero rest mass. The LHC will hopefully verify the existence of the Higgs Bosons upon resumption of associated research activities.

Now, if we can learn enough about the Higgs Bosons and associated Higgs Fields, perhaps we can determine how to shield space craft from the zero point Higgs Fields that supposedly give rise to finite rest mass and non-C transport velocities of finite rest mass particles, or in general, that of inertial bodies. Imagine converting a space craft and human occupants into a space craft traveling at C exactly. The space craft would in theory experience infinite time dilation thus enabling it to travel infinite distances in one Planck time unit ship time and infinity far into the future in the same Planck time unit ship time. Even if acceleration to C over a finite period of time associated with sub C inertia was necessary for time dilation effects, perhaps the Higgs field could be gradually reduced in such a way that the ship could accelerate inertially thru space over a finite period of time upon which the craft would reach C exactly.

The point I am trying to make is that it seems from the Standard Model, that the Higgs Field mechanism should exist and that there has been suggested a high degree of probability that the Higgs Bosons will be discovered with the upgraded LHC.

The various threads here at Tau Zero alone are replete with ideas about how to approach C closely from the many find commenters that post on site as well as ideas on how to do superluminal space-time travel. And this is just here at Tau Zero alone. If we find Earth like planets around nearby stars, I think the whole of the human scientific community, and even the whole of humanity, is going to eventually and relatively soon want a massive effort to develop the hardware that will send humans to these new worlds. I hope, feel, and think the fun is just beginning!

Paul, I get the feeling that both Centauri Dreams and Tau Zero will go down in history as famous visionary pioneering efforts in our journey to the stars and ultimately, our eternal journal ever further outward.

Thanks;

Jim

Lee,

Your point is well taken:

> “long before the ship arrives, humans will very likely be able to build much faster vehicles and overtake it.”

You’re absolutely right. And this is true for both a scientific probes and “manned” craft. But you’ve got an underlying assumption which you need to question. The assumption is that humans will survive long enough to construct faster ships. May be true. Sure hope it’s true. But what if it’s not?

I don’t think any of us can say with certainty that mankind cannot or will not develop technology which will destroy itself. I again quote Michael Anissimov at Accelerating Future, “Based on all the conversations and reading I’ve done, I consider humanity’s risk of wiping itself out in the next few decades to be substantial…” I think so too.

When one frames the rationale for an interstellar mission in the light of “preserving humanity” it makes all the difference in the world. It’s insurance for the human species. We may not need it. But if we do…boy, won’t we be glad we launched that mission even if it’s a “longshot”!

We would be launching this mission for the benefit of humanity — not for the benefit of the scientists. The scientists can take solace that they played a key role in purchasing the insurance policy for humanity. I think that the scientists and engineers would be perfectly satisfied just seeing the mission launched.

I am very encouraged with the discussion involving the 1400 +/- year mission and discussion about how long equipment would survive. If we recognize this sort of time range as feasible with current technology and reasonable budgets and then marry these engineering issues with the “insurance policy” rationale then we’ve got a tangible mission to look at and start working out the details. Without this intermediate focus I’m afraid that our attention and expertise might be distrated by either amazing technologies which none of us here will ever see or Daedaleus proposals which work good on paper but don’t actually get funded because of the sticker shock.

For an intermediate length interstellar mission I get the feeling that we might not use microcircuits but good old fasion vacuum tubes or something that wouldn’t so easily get knocked out by a cosmic ray.

But do tell. Enough water or hydrogen shielding can provide adequate protection from cosmic rays. But what width of this shielding would be sufficient to stop cosmic rays?

Also, charged particles from the sun are largely deflected by the Earth’s magnetic field. Cosmic rays travel so fast that they punch right through that field and hit the ground. But would inducing a very strong and long magnetic field in a superconductor be sufficient to deflect cosmic rays? If so and with normal micrometeorite shielding, what other hazards would remain during transit?

tacitus, re spam filtering, the answer is that full moderation is sadly necessary, as I’ve learned from experience. Akismet and other filters are a great help, but not enough.

Very kind remarks, Jim, and thank you. However large or small the contribution, it’s wonderful to be a part of this in some way.

Regarding the problem of faster ships following slower ships, I suspect a set of criteria will be defined as to when you should send a faster ship after a slower one.

First it’s not all bad sending two probes/ships to the same destination. An interstellar voyage is not going to be a cup of tea and the odds of one spacecraft making it alone is likely to be well below 100%, so contingency in the form of a second craft is not a bad idea.

By the time the first spacecraft is set to go, the designers will have a pretty good idea as to how much faster they can make the next generation craft (all the Mars probes use technology that’s mostly at least a decade or more out of date even when they were launched, such is the lead time required for spacecraft design and construction).

So after they launch the first spacecraft on its way, they begin work on the next generation with a specific speed increase in mind — say 20% or 50%. When they reach that design goal, they launch the second craft. It may get there sooner, or it may not, but the key thing is we would now have two craft racing to the target star and, if all goes well, twice the science or twice the payload (human or not) when the get there. If one of them fails, then all is not lost.

What you don’t do is wait another 10 years to shave, say, 10 years off the travel time. Unless there is a mammoth breakthrough just ahead, you go otherwise you may never go.

I hate to be a killjoy, but I don’t think any of these examples are actually that worthwhile. Both cathedrals and Hagia Sofia in particular can be built in much less of than a single generation, they also are maintained from the resources of an economy which dwarfs their cost of maintenance (or even construction) by orders of magnitude. Consider that at one point in time Hagia Sofia was in a quite dilapidated shape and might have been irretrievably lost without the extensive repairs and even extra construction (new buttresses) it received. Comparing this to a multi-generational starship where the economy that supports the continued operation of the vehicle is not as significantly greater than the cost of maintenance as any of the above examples is a bit of a stretch. More so, the examples of isolated economies we do have are rather hit and miss.

This is not to say that I don’t believe generational starships will be feasible, I think they are very likely to be feasible, but I don’t think anyone has yet put forward anywhere near a sufficient proof that they can or are likely to be.

Hi All

Two points. As Gerald Nordley has aptly pointed out a Near-Light drive means a starship can travel as quickly as it is able between the stars – to the crew the journey is less than the light travel-time. What can’t be done is a return to a homeworld that is recognizable – but very long-lived institutions might help ease that transition. An Office of Interstellar Affairs? Or something like Ursula LeGuin’s Ekumen?

Secondly, in reply to John – at sea-level we live under 10 tons/sq.metre of mass-shielding from cosmic rays which reduces the flux to about 40 millirem per year. In La Paz, under 6.5 tons/sq.m at 3,600 metres altitude, the flux is 200 millirem/year. There’s no apparent health hazard from this. O’Neill colonies were typically equipped with 2.5 tons/sq.m of shielding from memory, and that was deemed enough.

If you want more specifics read Paul Birch’s paper on radiation shielding – available at his website…

http://www.paulbirch.net/RadiationShields.zip

…for some reason his papers are zipped picture files of original pages (why???)

Robin, I don’t want to keep harping on a historical point, but I do want to note that the average European cathedral took longer than a single lifetime to construct — the number I keep seeing is 75-85 years on average, this in a time when the average human lifetime was relatively short. Usually these buildings were raised and supported by a local ecclesiastical community in an economy for which the construction would have been a considerable expense. When Henry III built the new eastern arm of Westminster Abbey, the cost of construction for that project was £45,000 in an era when the income from his entire realm was £35,000 per year. That one 25-year project took five percent of the total wealth available to the king for a quarter century.

So I don’t think we can say that the cost of construction was dwarfed by the resources available, especially not by orders of magnitude. In a new book on the subject, William Clark calls the cost of building cathedrals “…an enormous burden…imposed on towns in the Middle Ages.” And he goes on to talk about “…the frequent hostilities between emerging town economies and ecclesiastical overlords.” The Hagia Sophia is indeed a different case, but still of interest to me as an edifice that has survived for more than a millennium.

Now, whether the analogy is useful in thinking about multi-generational starships is another matter…

Adam,

You’re such a wealth of knowledge. I appreciate it.

So, 2.5 tons/sq.m = 2,273 kg/sq.m

1 sq.m = 10,000 cc’s = 10kg of water.

So one would need a depth of 273 cm or 2.73 m of water.

So the smallest amount of shielding (sphere) around a minimum of biologic material would be 4/3pi.r^3 = 27,000 kg of water = 29.7 tons of water.

So basically any shielding for biologic material would require a minimum of 29.7 tons? Ouch.

Also, 200 millirem/yr may be acceptable for those of us who live an average of 80 years but we’re talking here about travel times from 400 to 10,000 years. It could really add up.

So what about a very strong, long-lasting magnetic field using superconducting material? Might that be a practical way to reduce cosmic ray radiation?

Hi Folks;

A good example of how long a rigorous social system can last is that of the Catholic Church. In existence for about 2,000 years, it has maintained its moral and ethical system yet it has permitted doctrinal growth.

Another good example comes from the stability of the United States Constitution and political structure at least since the Civil War. We have not had major invading forces hit the U.S. since Pearl Harbor although some would say that the attacks of 9/11 were major invasions.

The UN is about 60 years old and still functions effectively in certain ways.

China has been a nation for thousands of years although they have had some upheaval at times.

With all of the excitement and enthusiasm that a slow interstellar mission could bring, I think we can go the long haul at terminal velocities of only 0.01 C to 0.1 C. High gamma factors would be great and FTL would be better yet.

Thanks;

Jim

Tacitus,

It’s a lot like my dilemma re: getting an iPhone. Do I get it now or wait just 6 months more because I’m SURE the rumors will come true!!!

On the other hand there’s a fairly cheap way of sending a second craft. After one develops the design and whole infrastructure to launch the craft it’s pennies relatively to launch a second craft.

If the craft were to contain living humans I would imagine that the catastrophic failure rate would probably have to be much less than 10%. That’s why I think that the first interstellar mission to establish humanity elsewhere will likely be in the form of frozen cells. That way the mass is low and we can bear more risk of failure because there’s no chance of loosing an individual.

Regarding multiple generations, I think that the Vision for Space Exploration already has a multi-generational dimension. We may not be landing people on Mars until 2030 and it will likely take 15 years or so to really build up that base. I’ll be well into retirement by that time. And it will be kids who are not yet born who will be some of the astronauts going to Mars. As for me, I’d just like to see a true interstellar mission launched within my lifetime.

I suspect I am in the minority, but I think the future of the human race will not be in colonizing other planets, but in building movable space colonies, not tied to any planet at all. The advantages of doing this over actually colonizing an actual planet are many:

With current techology or technology not that far removed from what we currently have:

We could generate gravity of 1g (spinning)

We could protect it from radiation (magnetic fields, water casing …)

We could move it out of the way of danger from large impactors(propulsion)

We could move it to resources that it needs (propulsion, to asteroid belt and beyond for example)

We could expand it to any size and take the pressure of earth in terms of human population (make it that way, cylinders can be extended or connected to each other)

We could adjust its orbit to gain the most out the star or whatever energy source it can be brought into the vicinity of (move it out from the sun as the sun gets older and hotter, move it back in as it cools for example).

We could leave planets bearing life (including earth) alone, to study from a distance, and not harm life, pollute, use up and destroy.

We could eventually leave the solar system, but there would be no rush to do so.

All these advantages can be put to good use inside our own solar system first, without sending out colony ships with the goal of putting that colony on another sitting target. This would greatly increase humanities survivability, without jeapardizing the life on other planets, that can support life.

Does anyone consider the impact of “colonizing” other worlds, on the life of those worlds? If we find a planet with life on it already, at whatever stage, do we immediately decide to send a million humans there and colonize it without any thought about what that might do to life that is already there? Is that all we are about, colonizing and spreading our species everwhere the conditions allow?

Ross, your excellent comment points up the need for the study of interstellar ethics. Robert Freitas has done some interesting writing about this. Particularly if we start deploying nanotechnology on potential interstellar missions, we have to consider what resources they might consume in assembling scientific stations to send information back to Earth. It’s one thing to land on an uninhabited asteroid. It’s quite another to land on a planet that has its own ecosystem, which should be protected in every way possible. All these things are going to emerge as serious issues as we move closer to having an interstellar reach.

Two useful Freitas references:

“The Legal Rights of Extraterrestrials,” Analog Science Fiction and Fact (April 1977), pp. 54–67, and “Metalaw and Interstellar Relations,” Mercury 6 (March/April 1977), pp. 15–17.

Any generational ship we might build in the next, oh, century, is one I would not embark upon. I very much doubt we’ll have the technology to make the voyage pleasant or successful. Regardless of any purported BBE (Big Bad Event) here on Earth, the probability of species and even personal survival is likely to be higher by staying put.

Whenever we do succeed in developing the technology to build a survivable multi-generational ship, I doubt it much matters where we point it. Since it will have to have a (mostly?) closed ecological cycle, and the people on board will identify the shipboard environment as ‘normal’, the attractiveness of settling any planet anywhere, whether sterile or containing native life, would likely be low to nil. Regardless of the purpose for launching the ship, whether for species survival, occupying the galaxy or simply exploration, the descendants won’t give a damn. They have it good on board. If they didn’t they’d already be dead. Ship speed wouldn’t even matter since the journey would be of greater perceived value to them than the destination.

If we were to insist that avoiding the (low, I believe) possibility of a BBE is best met with such a ship, it would likely be better to put it into, say, a 25-year elliptical solar orbit. That way if the crew gets fed up with shipboard life they can get off and be replaced by fresh ‘fanatics’, and if there is a BBE they can wait out the BBE and its consequences (e.g. radiation, hostile weather). Then, when conditions are right they can resettle the Earth. A post-BBE Earth is certain to be a more hospitable environment in comparison to any exoplanet, and much easier to get to.

Someone mentioned vacuum tubes. Forget it. Vacuum tube service life is far too short, despite its relative immunity to cosmic rays and other radiation damage. Solid state is the way to go. There is only the matter of improving the software and hardware technology for fault-tolerance and self-healing, and also carry along a compact semiconductor factory.

I understand your point, but from what I’ve heard from NASA engineers, the savings are not as great as you would expect. So while it would be cheaper, it’s more likely to be a little cheaper than a lot cheaper. I believe it’s to do with the cost of hardening and testing the components, which has to be done both times and where economies of scale don’t kick in till there’s a much higher volume in the pipeline.

I think the prospects of nanotechnology “going wild” on a planet’s surface are very remote unless it was programmed into them in the first place. Not that nanotech can’t be dangerous — but I suspect they will be dangerous by design, not by accident.

I’ve been (slowly) developing a story idea that involves nanotechnology as a side issue. My feeling is that we could at some point enter into a nanotechnology arms race where people will be racing both to develop nanotech weapons and nanotech defenses, and eventually we will all have to be inoculated with the latest nanotech anti-virus nanobots to keep us safe from malicious “bugs” we could encounter.

Dang! I came late to this conversation!

The only thing I would have to add is that this generational ship (assuming it could be built) would have to be fashioned out of “everlasting materials,” especially if it is going to exist in the deep, unforgiving environment of space for over a millennium.

The articles regarding radiation shielding which Adam referenced were very helpful. Thanks Adam.

After reading the article there is an answer to the question:

> Would inducing a very strong and long magnetic field in a superconductor be sufficient to deflect cosmic rays?

Yes, magnetic shielding using superconductors is easily able to produce magnetic fields strong enough to protect against cosmic rays to the levels so as to get radiation exposure levels down to 0.5 rem/year which is the accepted dose for the general public.

Also this may somewhat answer Darnell’s concern in that, at least the cosmic radiation side of the “unforgiving environment of space” has an engineering solution. Also, a craft taking 400 – 10,000 years would encounter dust and micrometeorites at a much slower speed than if we were traveling at relativistic speeds.

tacitus mentions the possibility of a future nanotech arms race. This very idea is discussed as a concern by the Lifeboat Foundation. I myself am not confident that defensive immunizations will always effectively counter every nanotech development before it appears. Our experience trying to develop an AIDS vaccine or even a malaria vaccine has been pretty dismal. I see no reason to think that we’ll do much better in the future.

When we think about the molecular level we shouldn’t limit our discussion to nanotech (i.e. motors, gears, conveyor belts, etc). We also need to think about self-replicating chemicals including novel ones without a biologic basis. This isn’t hypothetical. Researchers are actively working to figure out what it will take to produce such a thing:

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1200/is_n22_v146/ai_15952616

And when we get to molecular manufacturing it will be relatively easy to write a progam which would produce an incredible number of novel chemicals in a very short period of time.

I’m very late to the conversation, but it’s a subject I’ve always dreamed about. Personally I’m a fan of Ray Kurweil’s idea of the Singularity. An event brought about by the rapid transformation of the human race from a purely biological one to one which incorporates a great deal of technology as well. This Singularity may not be a good thing in the long run, but I do think it’s likely to be inevitable. The point is that building a generation ship sooner rather than later may be a good idea to avoid the possible fallout of rampant technology growth.

I agree that it may be a better idea to stay in solar orbit rather than set off to a new planet. On the other hand, if we are the only ones around in the general galactic neighborhood I’d like to see us find that out for certain and colonize other planets which don’t yet contain life.

If the technology of faster propulsion exceeds the speed of the first craft it would seem relatively simple to routinely send off upgrade ships full of the latest designs loaded onto the newest nanotech. Just intercept the generation ship with an automated nanoupgrade packet and let the little bots get to work rebuilding the whole system from its own material or new material grabbed along the way from passing meteors and asteroids. Presumably the tech would be sufficiently advanced to make up the time and being unmanned, the acceleration wouldn’t be an issue in the least. Wouldn’t such a system greatly reduce the travel time of the original ships as well as keep the colonists a little more in touch with the homeworld?

Another possibility is if we become capable of reconstructing entire humans who have had their entire body design uploaded to software, every single atom in place. We could catch up the generation ships and put copies of anyone who wants to go right there in the colony. Granted they would basically be clones and not in any way the original, but they would believe themselves to be the originals. There isn’t likely to be a contest between the two that could take place within either lifetime. This could even allow the original designers a sort of ability to see the ship’s arrival though with a giant gap in their memories of the travel time involved.

I want to sign up to have a copy of myself sent to every single colony ship sent out, hehe.

Interesting ideas, Charles, and I haven’t run into your ingenious suggestion about solving what Marc Millis calls ‘Zeno’s paradox in reverse’ — the idea that a faster technology will always outstrip ships launched earlier — in such an interesting way. Presumably this would work only if the new ships were not just incrementally faster but faster by orders of magnitude, but I like the idea of doing a nano-rebuild of an original design.

I really think we will see improvements in speed by orders of magnitude in fairly short time periods. We’ve already gone from a top end speed of 30mph in the early 1900s for the first cars to vehicles that could travel 300mph on land and 3000mph in the air. Not to mention the space shuttle which reaches I think 20,000 mph or better with gravity assistance. That’s all in just 100 years. Everything is improving so very rapidly and most of it is by orders of magnitude. I don’t think it will be too much to ask to expect this trend to continue as technologies accumulate to allow improved technologies to come to light. That is actually why Ray Kurweil believes we are inevitably headed for a singularity where our technology outstrips our biology’s ability to adapt without combining ourselves with the technology. Even without such massive improvements in speed, the really long range colony ships will be out there so long, there will be plenty of time to catch up at just a fractionally improved speed. It’s like passing a car going 65 down the interstate by speeding up to 70, still happens in a pretty short distance.

My favorite concept is that we will enhance our brainpower by orders of magnitude very soon as well. Any single individual who is enhanced by technology would literally be able to learn the sum total of all human knowledge in minutes. Imagine the possibilities for improvement of technology then. It may even outstrip the ability to weaponize it by surpassing those weapons before they are even built. Think of it… peace via instant obsolescence of war machines. Sorry for ranting tight off the topic.

Any multi-generational ship would need to be “home” to the inhabitants, large enough to be self-sustaining and heavy enough (shielded) to protect against any collisions (cosmic rays, micro-meteorites, etc). I think we will become a primarily space-dwelling race for many reasons I won’t go into. Eventually, we will have developed the confidence in our technology to just leave our solar system, while all the time being “home”.

The senario I forsee is the boring out of large metallic asteroids, set spinning for gravity. The interior surface area of such a micro-world could be as large as many states and have farmland, mountains, clouds and even an artifical sun. The interior metals and compounds would yield lots of metals and elements for sustenance, construction and commerce as the colony grew. An eliptical orbit around the solar system or inner planets, through the use of creative orbital dynamics, would allow inexpensive space freight and assist in commerce of mined resources. Eventually, stocking one of these hollow moons with embryoes (for bio-diversity), seeds, and resources would allow replication of similar hollow moons over and over, and even construction of fresh-built colonies.

It will be the main reason we work/live in space – for the resources and commerce. How else would you fund any permanent large-scale human presence in space? What is the value of 10 tons of metal in Earth or Mars orbit for constuction? Let alone the value some mined commodities will have on the resource-starved Earth. It will always be cheaper and easier to get material to build future spacecraft from space. Think how cheaply you could build and deliver the International Space Station or Hubble or a robotic probe inside a micro-world. Making the New World analogy, we came for spices and gold -eventually we made our own ships, cloth and guns and didn’t need to import much from Europe, we were primarily an exporter.

Eventually, we will put some of these micro-worlds in an orbit to the Oort cloud and then out to Alpha Centauri (or Proxima Centauri for a slingshot maneuver). They will not be alone and their lifestyle will be common, there will be thousands of micro-worlds eliptically circling the inner planets. Humans will become asteroid “viruses” spreading and colonizing any resource-rich heavenly body.

Eventually, we will “seed” the asteroid belts of all 3 of Alpha Centauri’s stars. Potentially, these 3 belts could contain the majority population of humans. If there are planets to colonize, we will, after much study and exploration – for it will be a one way trip. Developing the infrastructure to lauch a person back off the surface of an Earth-like world will take generations and will initially be of low priority (most of these people will initially be the Amish of the day, seeking a simpler life – with some scientists, explorers and entepreneurs). There will be some trade of critical elements between the New Earth settlers and the micro-worlds of Alpha Centauri and Earth (gems, platinum, and other rare and precious elements). Again, the New World analogy would be colonizing the easy-to-reach coastal areas first. People didn’t settle Denver for a long time and then only when we were seeking gold. Columbus to Denver was almost 400 years.

This is the commercially-viable, sustainable, natural, organic way we will settle space. There will be a Columbus (probes), a Jamestown (micro-worlds) and eventually Denver (New Earth).

keith,thank you very much for an interesting and imaginative way of looking at our perhaps not too distant future in space. again,and sorry if i’ve said this before, i am reminded of the original star trek episode “for the world is hollow and i have touched the sky” if you also recall that episode i am sure you will see my point. thank you very much your friend george

George, if I understand your point, I think you’re discounting the importance of communication with the outside world for trade, entertainment, etc. (BTW the Trek episode’s inhabitants home world was destroyed, they were alone) In other words, the witch trails of Salem (an isolated community) would have turned out differently if they had cell phones, internet, etc.

How often does the average person today leave their state/country? Yet we are still in touch with people and events in the remotest areas. How far of a leap is it from a Global Society to a Stellar Society?

What would you estimate the time required for any isolated modern society to decay without outside communication? Lord of the Flies, Branch Davidians, pick your example. My point is, it requires a large, diverse population and communication with the outside world to maintain the colony as part of society/humanity. Any long trip, or new colony for that matter, will require the same to avoid a Salem situation.

There’s so much to reply to. Fascinating discussion.

First, to the question of shielding from inertial mass. Quote:

“Now, if we can learn enough about the Higgs Bosons and associated Higgs Fields, perhaps we can determine how to shield space craft from the zero point Higgs Fields that supposedly give rise to finite rest mass and non-C transport velocities of finite rest mass particles, or in general, that of inertial bodies.”

This would be really nice. Alastair Reynolds plays around with this in a novel of his, Redemption Ark. Perhaps I should clarify the “really nice”, however, and say “if it didn’t kill us.” Why? Lengths in atoms and molecules are very sensitive to the masses of the particles involved: in the simples model, in a hydrogen atom, the s orbitals are roughly inverse to the electron-equivalent, which is why muonic fusion might work, by bringing the nuclei in hydrogen molecules closer together by orders of magnitude. Reynolds makes a lot of how the blood in the humans etc, the basic macroscopic engineering, is altered, and has nanomachines and cryogenics to help them survive, but doesn’t make anything of the fact that every molecular structure is to a greater or lesser extent dependent upon the masses of protons, neutrons and especially electrons.

And now tacitus.

I don’t think a grey goo scenario is possible, because our planet is currently inhabited with self-replicating nanotech which has been trying to do just that for billions of years – we call it “life”. If a self-replicating nanomachine of human design were let loose, I suspect that it could cause a lot of damage; possibly the end of civilisation; but I certainly can’t see it destroying all of life, because in the end, it’s only got a few more tricks up its sleeve than microbes which currently exist. It wouldn’t shock me if even a few humans had some degree of natural resistance, seeing as there are upwards of six billion of us at the moment.

Now to Keith Blockus.

I think this is really how it’s going to be. In the solar system we are going to have a reliable supply of energy for billions of years, and material resources for between thousands and millions depending on how fast we use it up. We don’t need to colonise Alpha Centauri or Epsilon Eridani yet – we have planets and moons suitable for life – albeit in domed environments or with extensive terraforming – right here. We have the Moon, Mars, the Galilean moons and those of Saturn, all of which could potentially harbour technological civilisations. Then there are asteroid habitats, all of that…

I dispute the suggestion that people who are renouncing technology would travel to the New Worlds of space. On Earth baseline humans can inhabit basically any reasonably hospitable environment without high technology, and have done for thousands of years. If you renounce high tech, or at least high tech societies, there is absolutely no way you could live on Mars, or on any prospective planets around other stars – and I say any of them, because even supposing they have life, there’s no reason we should be compatible biochemically so as to eat the stuff, but on the other hand microbes would be a danger to us simply because they can try out all the chemical pathways until they find one which can infect us. Our crops need soil to support them, and we couldn’t just sterilise apart of the planet with gamma rays or something and sow the seeds – we need whole ecosystems.

In an environment like that, anyone without sophisticated science and engineering would not be able to feed themselves and avoid natural hazards, let alone on planets which might not already harbour life like ours. To survive on another planet we would need at the very least scientific knowledge and engineering equal to or beyond today’s – I say equal to because we currently have quite a lot of know-how, and researchers able to obtain more, except we’re spending it drilling for oil and building guns and nukes to kill one another, and I’m confident that if we had a compelling reason to employ it for colonisation, and had the resources that we have spent on the Iraq War to pour into it, we could keep a colony alive in any environment which wasn’t too harsh.

Benjamin,

I should have said “different lifestyle”, not neccessarily simpler. The folks I refer to as seeking a simpler (or different) life on the surface of a Centauri planet (New Earth), would not be the trailblazers. I’m assuming smaller, earlier, faster ships would have visited and checked out the place and that New Earth isn’t particularly hostile, prior to colonization by a general population. I guess it’s just the definition you use for colonist versus explorer.

The New Earth colonists would have been on their micro-worlds for generations and some may seek a different life based upon their own goals and beliefs, not their parents. They won’t neccessarily be Luddites and reject tech, just immigrants (like Amish or Pilgrims). Many New Earth colonizers would have been discontent with life on the micro-worlds (for whatever reason: technology, religion, politics, etc). Many may descide to establish their own society. Eventually their descendants will get absorbed by the growing main-stream society.

Regarding the Amish reference, I do think there will be some people who descide to reject much of the tech beyond, say, the 22nd Century – they will be the “Amish” to the people of the 23rd Century. They will draw the line at human genetic manipulation, cybernetic enhancements, or maybe brain computer implants. We can only speculate what the emotionally and ethically-charged issues of the day will be and the impact it will have in a diverse society. They may just roll their eyes at “normal” cyber-people the same way I do at people walking into lightposts while talking to themselves on Bluetooth headsets.

My understanding is that magnetic shielding can reduce cosmic radiation damage to 5 rem/yr or less. Also Craig Venter has used the rapid DNA repair mechanisms of D. radiodurans in his Mycoplasma laboratorium. Add to that the aforementioned drug and it seems to me that cosmic radiation damage during long-term interstellar flight could be manageable. If the “human passenger” on an interstellar mission were in cellular form then some but not much of the life extension and cryonic research would be applicable to such a mission.

Looks like I’m years late in finding this discussion, but it certainly strikes a chord. I suspect the interstellar colonization by space habitat idea is the most likely, unless there we discover some way to by-pass the FTL limit. But, I would think such colonization will involve hundreds of self-directed interstellar transits, instead of some massive, intentional program: in other words, various space habitats will just decide to test the “waters” else where, and may, or may not, let the rest of humanity know. I think Blish (?) had a somewhat similiar idea with his sci-fi “spindizzy” Cities in Flight. I think large number of space habitats are guaranteed, simply by population growth. Excepting the unlikely possibility of an accidental human “die-off”, extrapolating human expansion in the last 500 years, there seems a strongly likelyhood of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of space habitats in our Solar System in another 500 years…and when humans get crowded, they move. And what’s a 1000 years to a new, uncluttered home.