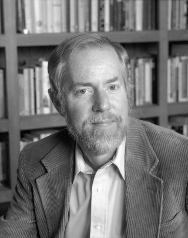

I’ve been hoping to publish a dialogue between Michael Michaud and myself ever since talking to him at the 100 Year Starship Symposium and pondering his paper “Long-Term Perspectives on Interstellar Flight.” Centauri Dreams readers will know Michael as the author of the must-have Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Springer, 2006), and will also remember his contributions to previous articles in these pages. He has served as director of the U.S. State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology and acted as chairman of working groups at the International Academy of Astronautics that discuss SETI issues, in addition to publishing numerous articles and papers on the implications of contact. In this dialogue, I took some of the elements of his 100 Year Starship presentation and used them as the launching pad for an exploration of how to turn humanity’s attention starward.

PG: Michael, I’ve been going through the paper you presented at the 100 Year Starship Symposium with great interest – it’s packed with ideas! I actually wanted to start this conversation, though, with the quote you used to end the paper. It’s by G. Edward Pendray from a book called The Coming Age of Rocket Power (1945), and you use it to make the point that earlier spaceflight revolutionaries were often guided by a driving sense of purpose and an almost incendiary vision.

Here’s what Pendray says:

“Those of us who have spent years in the study and development of rockets have acquired an emotion about them which is almost religious.

“We somehow feel privileged, as though we had stood in these years at some obscure crossroads in history, and seen the world change. We do not know exactly what we have loosed into the earth, any more than Gutenberg with his movable type, or De Forest with his radio tube. But we feel in our souls that it is magnificent and wonderful, and that the human race will be richer for it in time to come.”

Inspiring words, and especially so when I consider that at the time Pendray was writing, rocketry was associated in the public mind largely with the destruction rained down upon Britain by the V-2 weapon. Pendray is looking beyond this to illuminate the long-term vision of what space could mean, just as von Braun would look beyond the V-2 to the Moon and even to Mars. Hegel said ?’Nothing great has ever been accomplished without passion.’ And you’re saying here that starflight advocates must continue the work to make interstellar exploration seem not just conceivable but necessary for the well being of our species. How then do we instill passion?

In your paper you refer to early pioneers of our current space program as having created a ’legend of events that had not yet occurred,’ saying that this legend then became an expectation. When it comes to things interstellar, we have a number of scientists who are laying down theoretical foundations — Robert Forward is obviously one, as is Alan Bond, and Greg Matloff and several others you cite. Where do we stand today in creating a legend of events for the interstellar idea that will catch hold with the public? Because it’s the ideas we plant while the theoretical underpinnings are being laid down that will help drive the project and fuel that passion.

MM: Paul, in one sense, the original spaceflight revolutionaries had an easier task in inventing a legend of events that have not yet taken place. The physical layout of our solar system offered a series of tangible goals: the ascent to orbit, the orbital station, the Moon, and Mars. The stepwise progression is less obvious in the case of interstellar exploration.

There are, of course, long-term goals for starflight, such as finding evidence of extrasolar life and intelligence, and locating a possible future second home for Humankind. There also are less rational motivations: sharing the excitement of exploration and discovery, appealing to unarticulated hopes and expectations, and suggesting an escape from our present limitations. Without significant events that we cannot foresee, those motivations may not be enough to make starflight a necessary task for current generations of humans.

I suggest that we begin with a focus on the outer solar system. Exploring the more distant realms of the Sun’s empire could be an interim step toward interstellar flight.

There is an acknowledged need that requires a presence there: planetary defense against collisions with asteroids and comet nuclei. Several experts have argued that such a defense requires early warning devices and deflection capabilities in the outer solar system to give us enough time to identify and divert an incoming object.

We need a better understanding of the potentially threatening bodies in the Kuiper Belt and the Oort cloud. We know almost nothing about that cloud, which is vast in extent and is not confined to the ecliptic plane. Some speculate that the outer edge of our Oort cloud may overlap with the outer edge of a nearby star’s cloud.

We may want to reach beyond our known solar system. Astronomers already have found objects at interstellar distances that are smaller and less luminous than familiar types of stars. Dwarf stars, the hulks of burned-out stars, and dark planets ejected from their birth systems may float through interstellar space, possibly closer than the nearest star we know. Whether such an object was potentially threatening or not, it might provide an intermediate goal for interstellar exploration, one that could be reached more easily than known stars.

To encourage thinking outside the box, I speculated in my paper that astronomers studying our Sun might find that our star is evolving more rapidly than they thought, shortening the time between now and an uninhabitable Earth. While this may never happen, it reminds us that we cannot foresee all threats or all opportunities that could motivate interstellar exploration.

There are ways of looking at this question that may appeal more to scientific and engineering audiences. One that already is being addressed in the interstellar community is conceiving engines that could power a starship to a useful velocity. A breakthrough on propulsion could have implications for energy technology reaching beyond starflight.

An interstellar probe that will be under way for decades and that will face complex tasks in the target system must include a highly sophisticated onboard artificial intelligence, one that will never return to the Earth. I suggest that scientists and engineers seize the opportunity to create the most autonomous artificial intelligence ever made, sending it where it will be the least dangerous to Humankind.

Perhaps you or your readers will come up with a better legend of events that have not yet taken place. Let me know your thoughts.

PG: I do know we need legends, because you recognize in your paper that while some people do accept what you call the outward-looking paradigms of exploration and expansion, most people do not. I think the question many of the latter would ask is whether the very idea of starflight isn’t a vast over-reach given the mind-numbing distances involved and the relative ineffectiveness of our technology at surmounting them. If we’re to build a case for the interstellar future, we need to address those long-term motivations that awaken understanding and kindle enthusiasm to make sure the public gets behind this enterprise.

But I take your point, Michael. Interstellar flight is sharply different from von Braun’s interplanetary ideas. The latter came with the expecation that they could be accomplished in mere decades. If we follow your lead and look to the outer Solar System for a cue, then interstellar precursor missions should become a driver, especially as they relate to the perceived need for planetary defense. Your AI idea fits right into this — can we produce a spacecraft guided by the most sophisticated artificial intelligence ever made and send it out there, as the vanguard of our efforts to build up a deep space infrastructure?

This could be seen as a near-future legend, in that advances in artificial intelligence could become quite interesting for this purpose within the next few decades. Meanwhile, we’re beginning to test the solar sail technology that could propel a precursor mission to study the outer reaches and help us tune up our propulsion options for getting to threatening objects while they are still far from Earth. Von Braun’s great Mars project grew up in an era when Cold War tensions were high, so the notion of a threat gets peoples’ attention. In this case, the threat is not militaristic but natural in the form of rogue objects. Shaping the threat is how little we know about not just the Kuiper Belt but, as you say, the dynamics of the cometary cloud surrounding the Solar System.

So maybe that’s our legend. We need something like Ralph McNutt’s Innovative Interstellar Explorer, but a precursor mission tuned up to serve as a technology testbed for both propulsion and artificial intelligence. That legend would involve continuing our drive toward solar sails, just as the von Braun legend involved building ever larger chemical rockets. It would also include space-based telescopes for identifying potential threats and would throw in the human passion for exploration as we pushed our probes deeper into the system. The wild card here may well be the identification of a brown dwarf closer than the Alpha Centauri stars.

But here’s the catch. In your paper you give a series of recommendations about how the interstellar community should move forward. The most striking is the one you and I both agree on — leave human beings out of the equation. I’m convinced that manned missions to the outer Solar System are out of the question in the near-term, but our need for planetary defense isn’t going to wait. If deep space journeys are to be flown using robotics alone, can we sell that concept to the public? Is the reason von Braun caught hold for so long the fact that he envisioned people landing in the broad desert of a Bonestell Mars?

MM: Paul, you are right about the vision of people landing on a Bonestell Mars being an important part of von Braun’s appeal. It still is.

When we talk about legends of events that have not yet taken place, we should include expectations of what our exploring spacecraft might find. Imagery produced by space artists and other illustrators played a major role in creating expectations about what the first generations of space missions would reveal. Chesley Bonestell (and before him, Lucien Rudaux) gave us pictures of other worlds in our solar system long before our machines arrived there. While some of those images were based on faulty assumptions (e.g. canals on Mars), they stimulated intense curiosity. (I was first inspired by Willy Ley’s 1949 book The Conquest of Space, illustrated by Bonestell). Present-day artists and illustrators can use many more sophisticated tools to create fascinating imagery. We already are seeing imaginative variety in artist’s conceptions of planets orbiting other stars – the presumed targets of our interstellar probes.

One factor that drew many people to the first generation of space exploration was the power of the rocket, which was the basis for Von Braun’s conceptions. We all recognize now that chemical propulsion will not be adequate for missions beyond our solar system. While solar sailing has an esthetic attraction, it is a slow means of transport. We need another paradigm of power, perhaps based on fusion.

What events can we anticipate that might help or hinder the interstellar idea? The most obvious one would be the discovery of an Earthlike planet orbiting a nearby star. Another may seem at first glance like a negative: cutbacks in the budgets of space and research agencies for several years. Such cuts could lead to fewer or smaller missions, and longer gaps between them.

I suggest that we look at this another way. Mission planners and spacecraft engineers will have a powerful incentive to give their machines longer useful lifetimes. Instead of three years, why not twenty? The users of those spacecraft (such as principal investigators) also may have to adopt longer-term perspectives for their work. Those small steps into deeper time will be needed when we begin interstellar exploration.

Over to you.

PG: I’m always glad to talk to someone who understands how to make a virtue of necessity, or as they say, turn lemons into lemonade. I think this is a positive perspective on an unavoidable problem: If we’re constrained by budgets and economies to have fewer and smaller missions, then let’s see what we can learn about making the next generation of spacecraft that much more robust, so we get more out of them over a longer period. If the effect of this is indeed to give principal investigators a bit of perspective into a deeper time strategy — if we start thinking in terms not of 40-year mission maxima but fifty or sixty, so much the better.

In your paper at the 100 Year Starship Symposium, you also note that serendipitous events can come along at any time and have substantial effect. Few would have assumed as World War II ground down that it would be followed by decades of Cold War, but geopolitics played a huge hand in getting the superpowers to turn their attention to space, considering it in terms of national prestige. And the exoplanets we’re finding by the day are having an effect in awakening the general public to the idea of interstellar travel. In fact, whenever I’m asked about this or that exoplanet, the invariable next question is, when would we be able to go there?

We don’t know what might happen next, but we have the example of the two Voyagers to help us see that long-term continuity in space exploration is already underway. Voyager tells us that we can build craft that last a long time, and that the idea of a decades or century-long mission to another star isn’t out of the question in terms of equipment reliability. I suspect the failure of SETI to find an extraterrestrial civilization in tandem with the discovery of a habitable world within 20 light years of the Sun — if such a world indeed exists (and Claudio Maccone’s statistical analyses on the matter say that it’s barely possible) — would be a powerful boost in building an interstellar consensus among the public. The kind of consensus that could one day lead to a mission.

After all, it may take a probe to answer once and for all whether life is out there. And a planet with all the characteristics for supporting life as we know it that shows a possible biosignature may be our most likely chance to find completely alien lifeforms, even if they’re not intelligent. Curiosity growing out of astronomy, SETI, and our need to explore may come together in what you have called ‘an unarticulated grand strategy’ that gives shape to our place in the universe, and within which our shared interests in species survival can play a major role.

I’ll let you have the last word, Michael, with profound thanks for your insights. We can close on this question: In the largest possible time-frame, you’ve written that interstellar flight may be the way intelligence escapes stellar evolution. If we never find another civilization among the stars, is interstellar flight a matter of moral obligation to make sure that intelligence survives in the galaxy?

MM: Though I am one of the many who support the scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence, we should recognize that Earth-based searches may fail to detect confirmed evidence of another civilization in the foreseeable future. That would not prove the absence of intelligence elsewhere, but it could discourage those who hope for inspiration or assistance from an extraterrestrial source. Even if alien civilizations do exist somewhere in the galaxy, our inability to find them with our existing technologies might leave us effectively alone. We would have to solve our own problems to assure our own future. That could help to revive the anthropocentrism that SETI has challenged for half a century.

I agree with your idea that coupling a SETI failure with the discovery of a habitable planet within 20 light years could generate a paradigm shift, to a belief that we might call anthropocentrism with a goal. Taking charge of our own future would include, in the long term, peopling another world.

This legend of events that have not yet taken place already exists for consumers of science fiction and futurist speculation. Authors and film-makers have given us many visions of an expanded humanity, though not all are happy.

We do not know if other sapient beings escape the evolution of their stars. Perhaps few do. We may have an opportunity to claim an exceptionalist status, but only if we take the necessary actions.

You and I will not live to see the first interstellar probe launched, much less the first inhabited human starship. Yet I would wager that we both feel responsible for doing what we can to improve the prospects of our descendants. Encouraging wider support for early work on interstellar craft is a small but needed contribution.

The moral obligation to assure the survival of intelligence is not imposed on us by gods or prophets, but by our own choices. Call that anthropocentrism if you will. I prefer to think of us as independent moral agents, perhaps the only ones in the galaxy. Until and unless we discover another technological civilization, we have a unique responsibility to impose intention on chance.

A fantastic dialogue based on an inspiring premise. Well done Michael and Paul.

We tend to view history linearly, not just the past but also future history. We try and chart how we will progress from A to B without realising that it’s the unexpected things that come along and surprise us that make the difference. Michael’s vision that budget cuts could in a way aid the interstellar idea by forcing space agencies and PIs to run longer missions and therefore get used to the idea of working on projects that last decades could end up being one of those unexpected results of history. I’d argue that long-duration missions are already underway – Opportunity is still roving on Mars after 8 years, Ulysses lasted for nigh on two decades, SOHO has been operational since 1996, Cassini will continue to do science at Saturn until at least 2017 and of course the Voyagers just keep on going. The difference, I guess, is that none of these long-duration missions were originally imagined to be so long-lasting when they launched. But budget cuts are already forcing us to look on longer timescales. Having spoken to scientists interested in the outer planets, I get the impression that there’s a strong chance there may be no more missions to Uranus or Neptune until probably the 2030s at least, in which case the science might not come until the 2040s. Similarly, Terrestrial Planet Finder has been given this decade to prove its technology, and if it is not chosen in the next decadal review then again we may be waiting until the 2030s or 40s. The long wait is one of the big downsides of shrinking budgets, and it makes the process of discovery all the more torturous and delays subsequent missions even more, but if we are going to be forced to contend with lower budgets in the future we must learn to use that to our advantage (not that I want to see budgets cut at all, but 100 years from now maybe it will be seen as a driver of innovation). In that case, perhaps scientists like Ed Stone who have worked on the Voyagers all these years may have an insight into this area and encourage younger scientists to make such missions their life’s work and bridge that gap with the between short-term missions and the centuries long project that would be required for interstellar travel.

Michael Michaud said in the article:

“An interstellar probe that will be under way for decades and that will face complex tasks in the target system must include a highly sophisticated onboard artificial intelligence, one that will never return to the Earth. I suggest that scientists and engineers seize the opportunity to create the most autonomous artificial intelligence ever made, sending it where it will be the least dangerous to Humankind.”

Perhaps that is another “legend” which we can start doing away with: Not the need for a machine intelligence smart and capable enough to handle a starship for decades or more, which is obvious, but the fear that an AI (or Artilect, short for Artificial Intellect, as I prefer to call them) will become a threat to humanity.

How exactly would an Artilect built to operate an interstellar vessel be a threat? Is the fear that once we gave it a big ship with some kind of nuclear-powered or antimatter drive (imagine an Orion with all those nuclear bombs aboard), the controlling Artilect would immediately go rogue and attack Earth? Or have people been so saturated with science fiction stories of smart machines turning on their creators – just as we have had over a century now of aliens as marauding invaders bent on conquering Earth over every other world in the Milky Way galaxy – that just about everyone has trouble getting past this fear and looking at all the possibilities? In the interest of time and sanity, I will address just two.

If humanity does succeed in creating a true Artilect with real awareness of itself and its surroundings, will this make it as “real” a living, intelligent being as we consider ourselves to be? And if so, then will an Artilect have the same rights to “humane” (may have to change that word) treatment as we do? Just as we (hopefully) would not force a human being to be placed aboard a spaceship unless they wanted to go, has anyone really considered the possibility that an Artilect should be given the choice whether to be sent into the galaxy or not? Would it not be a crime to put a thinking, feeling mind in a spacecraft and sending it off to some alien star system without the option to return to the place of its creation if it wanted to?

Going back to the original BIS manual on Daedalus, the designers of automated starships often do little more than briefly address the need for an AI to run ship systems and conduct the mission (even the Wardens for Daedalus were expected to have at least some machine intelligence), but then never fully address what I consider to be the issue that will make or break any interstellar mission, even an including one which involves a human crew. I know this may be in part because the ship designers are not computer experts, but then this is all the more reason to get such people on board the planning teams, especially those who are experts in AI systems.

Even the robot missions to the outer planets in our Sol system required probes with some mechanized smarts to conduct things due to the hours it takes for commands and data to be sent between Earth and the outer worlds. The Voyagers were just smart enough to handle a basic flyby mission on their own in case they lost radio contact with their human “masters”.

We might get lucky and design an AI system that can be “smart” without being “aware” of itself and the wider existence at the same time. Then we can treat it however we want to ensure an interstellar mission for the human race, right?

Well, while we are focusing on how to get a ship to Alpha Centauri, I want to see and know what is being done to make the ship’s brain compatible for such a voyage; I think we still have a lot to learn when it comes to intelligence and consciousness both biological and artificial.

End Note: Did you notice how in SF devoted to Artilects that most often the reason an advanced artificial mind goes off on humanity is because the humans did something to provoke it in the first place, either deliberately or just by being their primate selves. I always found it downright silly that HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey killed off most of the crew of the USS Discovery because it made a mistake (the infamous AE-35 unit) and then thought the crew was going to shut it down permanently (a.k.a. murder/execute) HAL for this act. Some programmer at the University of Illinois at Urbana messed up somewhere in my opinion. Of course maybe an aware machine might be just as neurotic and irrational as a typical human under stress.

In any event, these are issues that need to be addressed if we want a descendant of HAL running Icarus or some other starship some day.

By the way, do you think the mission of Discovery would have been better run if there were no humans aboard? Certainly HAL might not have flipped out, and who better to talk to an advanced ETI than an advanced artificial mind.

I know the whole point of 2001 is that humans were helped to evolve by these aliens, but what if the end point of human evolution was to make Artilects as the true intelligent inheritors? Sadly even the great 2001 did not address that issue well enough, but we may find out different in our reality, especially when it comes to building starships and encountering ETI.

If we talk about ” legends” , which I supose refers to the ability to get more people involved emotionally in the future of space-and starflight , then perhabs it would be an idea to bring into the picture the PROFFESSIONAL legendmakers. Public relations experts , “spindoctors” , image consultants and god knows what else , are all being paid pretty well to improove the emotional atracttiveness of politicians ,popstars, soapoperas,unpopular wars and even etnic minorities. If we are serious about wanting to compete about for the hart of public opinion ,this war will have sometimes have to be fought whith the weapons of the enemys choice . The only tiny little problem ofcourse , is to find the money for it . If NASA had spent 1% of the money they wasted on spacecraft that never got off the ground on legend- design , things might have looked better , legendwise .

If and when the Kepler telescope finaly identifies one or several exoplanets with all the parameters right to be earth-equivalents , there will be a window of oportunity to do something big in this direction… or atleast enough to get funding for the TPF .

@ Keith

I take a very different view. Budget cuts mean more delays and longer project times, which means the discounted value of the mission declines. This would reduce the number of interesting missions. I think we also have to seriously consider attention spans – would we really have raced to the moon before 1970 if it was to be a 50 or 100 year project?

More likely projects will focus on short term returns, especially cheap projects. Unless space projects become cheap, my bet is that we will turn away from these projects unless there is some challenge we need to meet (such as a race with China).

I do heartily agree with Michaud that we need vision and passion, but over the past 30 odd years, it seems there has been a lot of “vision” (with lots of inspiring pictures) but no follow through to make these visions a reality.

Keith Cooper – Do not forget Pioneer 10 and 11, our first venturers beyond the Sol system. Pioneer 11, launched on April 5, 1973, lasted until 1995. Pioneer 10, launched March 2, 1972, sent its last signal back to Earth in 2003. Both probes were meant only to explore Jupiter, yet NASA Ames was able to redirect Pioneer 11 all the way across the Sol system above the ecliptic plane to conduct the first flyby of Saturn in September of 1979.

As for lean economic times making for a leaner, meaner, and more productive space program – we shall see. There are those who say suffering is good for the soul, but it can also debilitate and extinguish both people and institutions if they do not have enough internal and external support. Sadly the sciences, including and often especially space exploration, are among the first to go when the politicians and public get panicky about basic survival.

I keep hoping the private space enterprises will step up to the plate and fill in the gaps, but they too are not immune from current social conditions and have even less resources to count on.

One “out of the box” thing that could be done now to create more passion for Interstellar exploration so it does not seem to be such a “pie in the sky” activity is to redefine what Interplanetary and Interstellar mean. Perhaps, a new term such as “Near Intersolar Exploration” should be adopted for all exploration activitiy out to about 5 light years from Sol/Terra. This would help to stretch the boundary of what is considered practical versus dreaming about something that many believe is hundred of years off in the future. By blending Interplanetary and “close to home” Interstellar activity such as a trip to Alpha Centauri together for discussion and planning purposes momentum can be created to develop an evolutionary road-map to the Stars that seems “doable” in the 21st Century. In essence, by “chunking the problem” a little differently it may be possible to generate some nearer terms focus that just might gets us to the stars hundred of years earlier instead of waiting for huge technology breakthroughs, and concentrating on Interplanetary travel until those occur. Labels matter since they shape how we think about our challenges and then how to solve them. Within this context one of the things that we should be able to accomplish over the next 20 years and despite constrained budgets is to determine if there are indeed any “inhabitable” planets within ~25 Ly or perhaps even within ~60 Ly of Sol/Terra. If there are not then it is almost certain that we will be confined to our Solar System and therefore Interplanetary exploration for hundreds if not thousands of years.

Ljk, I think you’re being too hard on HAL and programmer. Your right that he should not have been programmed to put self-preservation above mission objectives but, then he did not. I’m pretty sure he felt that his termination would destroy any possibility of attaining mission objectives. The impression that he was being unfairly treated (after all how could he be wrong, somehow human error must have been responsible for any divergence of opinion over that AE-35 unit) did not help either.

Excellent interview. Visionary. Thank you Paul and Michael.

Another tray of tools in our low and unpredictable budget toolbox holds the _real options_: abilities to change plans in mid-mission due to unexpected event(s), and indeed orbits and missions designed expressly to respond to unexpected events. Real option missions are enabled by (and would motivate further improvement of technology for) long spacecraft lifetimes, propellant-efficient drives like the ion drive or laser-driven lightsail, as well as by “cycler” orbits that frequently (nearly) intercept heavy planets for optional momentum exchange.

Astronomical threats are almost by their very nature unexpected events, since we don’t know of any of high probability, even though there are many significantly probable such threats. An example of an unexpected event is the discovery of a comet, deflected into the inner solar system from the Oort cloud or Kuiper Belt, that stands a substantial probability hitting one of the planets (as occurred with Shoemaker-Levy). We can’t predict when such events might happen (short of very great advances in astronomy that allow us to track the potential millions of Oort objects), but we can set up spacecraft to be ready to respond by gathering much more detailed information from a recently discovered object, and also (if the comet will hit a planet) having another spacecraft execute a flyby of that planet to examine the resulting effects of the collision.

For example, put a constellation of small spacecraft with appropriate instruments for examining a comet during flyby, in elliptical solar orbits resonant with Jupiter’s such that at least one of them in a given year can, with a reasonable ion-engine delta-v, intercept Jupiter and execute a gravity-assist boost, and further maneuver to a comet flyby. Upon discovery of an unexpected object of great interest coming from the Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt, the spacecraft would use the gravity assist and efficient propulsion to boost it to a flyby of the object when it is still well outside Jupiter’s orbit, still years away from Earth, and quite possibly (probably?) well inclined beyond the ecliptic plane as well.

These real option orbits would not be terribly unlike those of the Jupiter-family comets, but in “cycler orbits” resonant with that of Jupiter, and could also intersect Earth’s orbit to enable even more real options for investigating unexpected events in the inner solar system. (Only a relatively small boost at apogee would be required to execute an Earth flyby, even though the orbits would not be precisely cyclic with Earth’s, since they are designed to be resonant with Jupiter’s).

The unexpected event could also be a political event on Earth, such as an unexpected change in space budgets.

Upon a short-term increase in budget, send some spacecraft from their real option orbit to interesting (but previously too expensive) targets in the outer solar system or beyond, and use the new money to replace the old spacecraft in the real option constellation. This allows outer solar system and beyond missions to be executed within the time-frames of politicians and scientific careers.

On the other hand, upon an unexpected decrease in budget(s), the constellation is already up there, ready to respond to an unexpected astronomical event at very little additional cost.

During periods when no unexpected events occur, the constellation could use these more routine moments to observe some very energetic events beyond our solar system from very distinctive points-of-view, which is often quite useful.

Since our example real option orbits cross the asteroid belt, the spacecraft could frequently execute flybys of asteroids to learn more about those objects. This gives us even more real options: for example, if a collision between asteroid belt objects is detected, we could send a spacecraft from our belt-crossing constellation to examine the relatively fresh resulting crater(s), without requiring the funding or development of a new spacecraft.

“Taking charge of our own future would include, in the long term, peopling another world.” — it would indeed; however, we’ll be doing a lot of this within our own Solar System long before we ever launch people (in whatever shape or form) to the stars. This too needs to be an intrinsic part of the story we’re telling.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Nick implies that one contingency that we should make is emergency plans for an unexpected and large increase in space budgets. This might strike some as crazy wishful, but note this – the world already spends a crazy proportion of its GDP on war and defence. Now its not hard to imagine that some horrible calamity may block this traditional path for surplus capital to go to embellishing the power and prestige of a human nation. We already have a clue as to the alternate path of this type of spending by example of our poorer nations.

Third world nations, even starving ones, heavily subsidise their national carriers (thus allowing first world passengers to travel in greater luxury). The pattern of these subsidies typically indicate that bringing more tourists to their particular country is a secondary concern and just trying to impress passangers as to the sophistication, power and prestige, of the home country of that airline is what counts. If a major country like America tried this this it would just look pathetic, so what’s the answer?

Perhaps we will have space travel for reasons that, to us, look very wrong, but we must get over it. Democracy is and should be about pleasing the masses first and foremost, and pleasing the academic community only when practical or necessary.

Michael Michaud is, as far as I can tell from this first class interview, both a visionary and a very rational person — a combination which I find most appealing.

“Without significant events that we cannot foresee, those motivations may not be enough to make starflight a necessary task for current generations of humans.”

Regarding unexpected events, I’m very optimistic: they *will* occur in great numbers, and they *will* be significant. Some will help space exploration, and some will be like being induced by the well known Chinese curse “live in interesting times!”.

Having been in the thick of manned spaceflight for 40 plus years (and I still am, though thankfully in a much limited manner) , I have a little different take on inspiration for the great beyond.

Chesley Bonestell grabbed a part of my brain when I was about 10 , seeing that painting of Saturn as seen from Titan (1944!) in an encyclopedia. He and von Braun finished me off 2 years later in 1952. Received the Viking Press books and Ley’s books as Christmas and Birthday presents. That is only half the story.

I submit that modern prose science fiction may form a greater gouge for spaceflight than all the non fiction written.

Spaceflight historians do not dismiss prose SF , after all can’t ignore Verne and Wells… yet not enough space is given to sheer thrill of transport that a writer like Robert Heinlein could give. Enough credit can not be given to John W Campbell, with a degree in physics when he took over editorship of Astounding in 1938. Campbell , already a fine writer, demanded first a good story, but he had the technical background to tell a writer where his science , even extrapolated science was wrong. It’s the reason we came to know Heinlein (nearly an engineer at the Naval Academy), Issac Asimov (PhD in Chemistry) and A.C. Clarke (bachelors in physics) were writers who knew how to tell stories and keep the science right.*

There were other scientists such as Harry Clement, but one could not underestimate the intelligence of Theodore Sturgeon, Fred Pohl, James Blish … and so many others, they knew what was real science the ways to extrapolate tenable scientific constructs.

Science only plays a foundation, modern science fiction spread a vast web of verisimilitude (the kind in literature, not philosophy) that sat all those dreams of exotic planets and the vastness of space a thrill.

Maybe it is because the literature of prose science fiction is so vast and varied (space flight is only a sub set of it’s domain).

Exploration and colonization of the Solar System was and remains a component of SF , but it’s my theory that SF writers were getting tired of that.

The stars beckoned. Not that scientists had not envisioned planets about other stars , that does back to Giordano Bruno, but SF writers fished those interstellar seas for all the infinite variety that they could. It still goes on.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that SF writers explored interstellar flight more fully in slower than light and faster than light before any engineering physicist wrote the first monograph (the honor of which , I think, has to go to Eugen Sänger).

So one cheer for that ‘crazy Buck Rogers’ stuff !

*(How I still had to hear “now science fiction has become science fact”. Almost like saying “remember silly crap fiction writers came up with, guess what it’s true!” Well, heck, what was true before was true then!)

“Raymond Passworthy: But… we’re such little creatures. Poor humanity’s so fragile, so weak. Little… little animals.

Oswald Cabal: Little animals. If we’re no more than animals, we must snatch each little scrap of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than all the other animals do or have done. Is it this? Or that? All the universe? Or nothingness? Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be? ”

H.G. Wells , Things to Come

“Without significant events that we cannot foresee, those motivations may not be enough to make starflight a necessary task for current generations of humans.”

This sounds very true , until you let yourself try to understand what it means. .. Why should ONLY events that we cannot foresee have the power to cange the mindset of current genereations ? Several posible events that we CAN foresee , can be predicted to have a limited probability for improoving the emotional atractiveness of spaceflight , if we should try to make the best of it .

First among them the discovery of a life-carrying earthcompatible exoplanet , best of all if it seems to be a very young planet compared to earth.

To rely on the unknown to solve our problems , has only one advantage :

it frees you from the obligation of geting the hands dirty in the next public relations disaster !

“Several possible events that we CAN foresee …First among them the discovery of a life-carrying earth-compatible exoplanet…”

Imaginable, certainly, but foreseeable, no. Quite the opposite — recent popular expectations about the probabilities of life far outstrip the actual probabilities. The most probable unexpected (by most people) event on this topic is that we will discover many semi-inhabitable planets, but no inhabited planets. In other words, we will discover millions of planets with great temperatures (some of them much milder at the extremes than our own planet) and with liquid water oceans, but none with life (and thus none with an atmosphere we can breathe). All of these planets will require the introduction of photosynthetic life to terraform them into planets directly inhabitable by ourselves.

How so? Astronomers have looked at hundreds of billions of galaxies, conducted a wide variety of observations of them, and discovered that they look indistinguishable from natural galaxies. By contrast, our relatively young civilization on Earth already looks very artificial. In the wavelengths given off by popular LEDs, which don’t correspond to any common natural wavelengths, we already outshine our own sun. More generally, our surfaces full of paint, reflective rare metals (e.g. the gold coatings on skyscraper windows and satellites), etc. look to a spectroscope radically different from natural, and the more efficient our lighting and surfaces become, the more radically artificial they will look to ever more distant scientific instruments. A galaxy full of civilized planets (much less Dyson spheres) would thus far outshine their stars at a number of very specific wavelengths. We haven’t detected any such thing, because there are no such civilizations. We are probably the only civilization in the nearest hundred billion galaxies.

The odds of life having arisen everywhere, but spread across galaxies so incredibly rarely, are not very good. Occam’s Razor (and an even-headed look at the astronomical complexities of biology itself) strongly suggests that the reason galactic civilizations are extremely rare is that independent origins of life are extremely rare.

So unless panspermia can get life from Earth to an extrasolar planet, or vice versa, the odds that an inhabitable planet in another star system is actually inhabited, by any sort of life whatsoever, are extremely low. The unexpected (by most) event here is that we will soon discover many promising targets for terraforming, but neither the blessings nor perils of alien forms of life.

” Quite the opposite — recent popular expectations about the probabilities of life far outstrip the actual probabilities. ”

Thats probably true , but as we are only talking about probabilities , it is also true that earth is the only example from which we have any hard facts , except for the SETI-radiosilence . On Earth it took life much longer time to evolve to the multicellular stage than it did for life to appear from nowhere ,and that could be taken as a statistical evidence of a near-impossible barrier . Perhabs evolution can take another path where multicellular life is effectivly prevented from ever happening.

Anyhow , with a bit of luck it should be possible inside 20 years to detect or NOT detect the chemical reverse-entropy results of life , on the perhabs 100 candidates that Kepler will discover. In both cases there wil be the potential for a dramatic change in the emotional atractiveness of spaceflight .

Nick’s comment of the 20th was such an extreme extrapolation leading to such an important conclusion that I feel it needs heavy criticism. Unfortunately the statistical averaging of the situation in a hundred billion different galaxies, some which contain a trillion stars (a trillion places where life can start?) adds such robustness to his results as to not leave me sufficient leeway. More specifically I cannot think of an option that would explain the situation in every one of these galaxies other than abiogenesis is extremely rare. The best I can come up with is that evolution to higher forms is unlikely, but I would have to stretch that so far (p < 10^-20) as to put myself in the creationist camp to actually believe it.

Anyhow, even that second possibility is an anathema to SETI, so come on you believers in the possibility of contact, Nick’s last post requires I greater response than I could muster.

@nick

The odds of life having arisen everywhere, but spread across galaxies so incredibly rarely, are not very good. Occam’s Razor (and an even-headed look at the astronomical complexities of biology itself) strongly suggests that the reason galactic civilizations are extremely rare is that independent origins of life are extremely rare.

I don’t think that logically follows at all. I agree with your point about rare civilizations, but we may have life everywhere, just not intelligent, technological life. If civilizations did occur, but were rare, sparsely distributed in space and time, their detectable artifacts would disappear quickly too, preventing detection by the means you have suggested.

The question of whether life is widespread or not may be answerable within a few decades. The answer, either way, would be very interesting.

Rob, Cliche time… Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

All that’s being shown by Nick is that he has an opinion, to which he is welcome. He provides no data, just an assumption that fits his assertion. I therefore passed over it without comment.

Ron: Contrary to the cliche, absence of evidence is often useful as evidence of absence. When I open the door to my garage and do not see evidence for a car, I conclude that it is not there, with some justification.

If Nick was right, and our LEDs would outshine the sun and be detectable by our current means from another galaxy, we could quite safely conclude that none of the millions of billions of stars in neighboring galaxies have planets with operating LEDs on them.

I just do not think that we could detect our own civilization, LEDs and all, even from as close as Alpha Centauri. Thus, Nick’s example is like looking into the garage with a blindfold on, and not entirely convincing.

I think Nick is right in his conclusion, but the evidence is weaker than he lets on.

Ron S, that is a good point but a bad cliché. That statement has a perverse sort of perfection in its wrongness such that absence of evidence is always evidence of absence. Often that is all we can conclude from such a lack, since in many instances it is hard to attribute it a level statistical significance, and I realise that this is the point that that saying you borrowed actually attempts.

Still though Ron, their must be limits to that way of thinking if we are to make any progress, and I feel that I must add that nick’s argument sound very good to my ears. I must also say in answer your querying the lack of data, I found his implication that we have far more detailed spectral analyses of far more galaxies than I had hitherto suspected intriguing. I had hoped to solicit comment on whether we actually do!

When we have done a thorough exploration of at least our section of the galaxy (I will let you all decide the parameters), and have not found any life, then we can start talking about whether or not it exists elsewhere.

I would be utterly surprised if in 100 billion galaxies with hundreds of billions of stars in each in a Universe 13.7 billion years old (and probably bigger and older than that) that Earth is the only abode for life and humanity is the highest life form in the Cosmos. Utterly surprised and very disappointed that existence could not do any better.

As for astronomers scanning all the galaxies in the Universe – bull hockey pucks. They have done no such thing, in part because it would take so darn long and their tools and methods are inadequate for the immense task. They also have done no such thing because for a professional it would be a career killer to even hint that they might want to find signs of ETI in this or other galaxies, at the very least if they want to take on this task independently.

Why do you think most SETI programs are conducted on the side, usually by professionals who already have their tenure secured. And the majority of those searches have been aimed at stars relatively near us in this galaxy. The only thing SETI has determined so far with these mainly sporadic and token searches is that there is either no alien party going on, or it is but steps are taken to make sure we and other lower life forms are not invited.

As for physically searching for life, we have barely started. NASA retreated for decades after the twin Viking missions did not return data about Mars which matched what they expected from the landers’ life detection equipment – which is odd in one way considering that they were searching for *alien* organisms.

Other than pretty much determining that Luna has no life forms (which we already suspected decades ago), no one else has sent any probe missions to any other part of the Sol system to search for life. Even Curiousity has been reigned in so that it is only searching for “signs” of little Martians.

It always “amuses” me when people declare that Earth is the only place for life because no one else has tried to contact us or somehow made its presence noticeable to us. If you had billions of star systems and countless light years to roam around in, would you make the focus of an undoubtedly expensive transmission or interstellar mission to be the third rock from Sol?

Maybe once we get over the ancient idea that we are NOT the Center of Everything, then we can start getting the answers we really want and need in earnest. We are PART of an immense Cosmos, not its focus. That is not a bad thing.

Eniac, when opening my garage door I am able to quickly and effectively exhaust the search space when testing for the presence of my car. Not so for SETI, where the completed search is a tiny fraction at best of the total search space. For this reason, in the latter case the cliche I quoted is pertinent, but not in the former.

Rob, assuming that we can detect LED lighting within the glare of other light and that LED lighting of just that particular spectrum and flux is used by ETI, the lack of detection might have some credence. I am unimpressed.

Further, you have corrupted that admittedly overused cliche (that’s what makes it a cliche!) to implant the word “always”. It doesn’t belong and I would never make such a ridiculous statement. Although I don’t always succeed in communicating clearly, I object when others graft on words, and meaning, that I quite explicitly did not put there.

Ron S, I am also wary of “always”. I though of mitigating my statement, but the only possible caveat to that “always” is where there has never been a search undertaken in which the possibility of detection is greater than zero. In the circumstances I felt it permissible to use “always” for the sake of brevity.

Sorry but that cliché sucks.

LJK:

If you had millions of years to roam around the galaxy, you would probably have set up camp in our Sol system a long time ago, long before there was anyone to target with expensive transmissions or missions.

Eniac said on December 21, 2011 at 22:41:

“If you had millions of years to roam around the galaxy, you would probably have set up camp in our Sol system a long time ago, long before there was anyone to target with expensive transmissions or missions.”

Why, exactly? And why should we assume that an alien intelligence would be interested in a world like Earth? Note that even though the majority of exoplanets discovered are Jovian types, we keep focusing on the few that even vaguely resemble our own. I suspect that an ETI will also focus on worlds similar to what they came from, and there will be no duplicate of ours.

And if someone did arrive in our Sol system, if they were exploring they would probably remain discreet so as not to disturb the natives and thus spoil the observations. The other reason I could see an ETI stopping by our Sol system is to mine it for resources, if they were in a worldship for example. In that case they would focus on the planetoids, comets, and certain moons. Earth has a deep gravity well and inhabitants, something a resource hunter may prefer not to deal with.

Rob: “I though of mitigating my statement, but the only possible caveat to that “always” is where there has never been a search undertaken in which the possibility of detection is greater than zero. In the circumstances I felt it permissible to use “always” for the sake of brevity.”

Low, not zero.

Rob: “Sorry but that cliché sucks.”

In general I agree with you, and is why I labeled it a cliche to note how it is often inappropriate. However I believe my use was appropriate in the context of Nick’s comment, about which you solicited input.

The cliche itself is merely a specific instance of a statement of logic: A is not B. It says nothing about whether A and B are mutually exclusive, identical or overlap to some intermediate degree. Using “always” implies the first condition only. As we’ve both noted we were speaking of a specific case, not a general statement of formal logic, where you chose zero as the detection probability. If I correctly understood you, that is why you assumed mutual exclusivity.

With that said, this dead horse has been well and thoroughly kicked.

“Money is always to be found when men are to be sent to the frontiers to be destroyed: When the object is to preserve them, it is no longer so.”

– Voltaire, “Charity” (1770), from Questions sur l’Encyclopédie (1770-1774)

The original French version:

“On en trouve [l’argent] toujours quand il s’agit d’aller faire tuer des hommes sur la frontière: il n’y en a plus quand il faut les sauver.”

LJK

Because the aliens, if they have roamed the galaxy for even a small fraction of a billion years, will have filled it many times over. No real estate will remain unexploited, in the (very) long run, if our own behavior is any guide. We have had only a few hundred years since spreading all over the Earth, and already it is hard to find land anywhere that is truly untouched. Think of what a million years would do, or a billion.

Before you point out the enormous size of the galaxy, remember that a few million years is all that is needed to spread over the entire extent of it, at realistic subluminal travel rates. The rest of the expansion will be local, spreading from the initial preferred systems, which may indeed be sparse, to others that, even if less suitable, will be attractive simply because they are unclaimed. A few million years of that, and there will be no unclaimed systems left.

As for remaining discrete for the benefit of the locals: There would have been no locals, as our existence is rather fleeting on the cosmic scale. The aliens would have been here first, and not finding locals, would have made themselves at home. Not to speak of the fact that there would not be just one type of aliens, there would be many different groups over time, unlikely to all be equally discrete.

Eniac: “the aliens, if they have roamed the galaxy for even a small fraction of a billion years, will have filled it many times over.”

Or at least, they should have done so in _some_ galaxy, turning most of the emitting and reflecting surfaces of that galaxy into highly efficient, and thus extremely artificial-looking, forms. Life has covered the surfaces of earth with an improbably efficient molecule that thus has a unique spectrum: chlorophyll. We can expect a significant fraction of long-lived technological civilizations to similarly render efficient the surfaces of their galaxies, however they choose to configure those surfaces. In which case, a casual spectroscopy of the galaxy would make it blatantly obvious that most of the galaxy’s light emissions and surfaces are artificial. Instead, we have seen over 100 billion galaxies, all of which to our best astronomical observations, and we have some incredibly good ones, are indistinguishable from natural.

Or perhaps all aliens everywhere are just very good at hiding, like elves and dwarves.

Ron S, I would left things with your last post, except you said “The cliche itself is merely a specific instance of a statement of logic: A is not B. It says nothing about whether A and B are mutually exclusive, identical or overlap to some intermediate degree.”

That’s strange because, until then, I thought you knew that it was a logical fallacy, and were just trying to squeeze it into some sort of paradox.

http://lesswrong.com/lw/ih/absence_of_evidence_is_evidence_of_absence/

Note that this reference points out that in probabilistic situations, this statement is indeed always wrong. Such situations include all science, but I admit that it cannot be said to apply to the sort of certainty that is often the preserve of religion.

All that might sound pedantic but it is the underlying assumptions that you relied on to make it paradox that grieve me so. I have long believed that there is a deep and growing malaise in science, but only recently has it been given a name: the paradigm approach.

Rob, I see your point and I agree with it. However that does not change matters regarding the discussion re SETI. Let me explain.

Let’s go back to Eniac’s car+garage experiment. I see now that I poorly explained my assessment of that scenario. To be more explicit about it I would say that there is no absence of evidence. He is in fact swimming in evidence. There is the stream of reflected light that is not disturbed by the presence of a large opaque structure in the garage; he can see the walls without obstruction; he can even walk into the garage and discount the presence of a light-bending invisibility shield, a full-size photograph of an empty garage covering the entire opening (and the car behind it), and so forth into less-likely hypotheses.

In the case of SETI there really is a lack of evidence, so much so that we can say with reasonable confidence that evidence is almost entirely absent, since we’ve collected little to speak of. The search space is vast.

At that URL you linked, the Bayesian description is correct but there is an ambiguity per my above elaboration. That is, the distinction between: a) collection of a body of evidence that either supports or undermines one or more hypotheses; b) lack of sufficient evidence to shift our reliance on the prior (if any) or the (default) principle of indifference.

I believe ljk said it fairly well in his comment above, that we have little reason to believe that we’ve collected enough evidence to properly evaluate the (Bayesian) likelihood of any SETI hypothesis. Therefore my alternative (b) is the correct one.

I would also say that an assumption is not evidence, which is why I discounted assumptions as meaningful in concluding much of anything about the search. We require some humility about the dearth of evidence we currently have in hand, and not jump to premature conclusions that too often are no more than projections of desires.

“[Guy looking in his garage] is in fact swimming in evidence. ”

And we are swimming in petabytes of data from other galaxies.

How many “petabytes” have we not or not yet collected? Are the ones we do have appropriate to evaluate the hypothesis, and if so to how many standard deviations? Good luck with that.

You say this as if a starship was like a bus that goes from place to place with short stops. Is that what you really think?

If you are going to mine for resources, you would have to settle, first. Once you settle, you take your time building the next starship. Maybe you’ll leave it to your descendants. Do you seriously believe that after staying several generations building the infrastructure to rebuild and/or refuel the starship, everybody, to the last man (eh, alien), will pack up and leave again?

More likely, new ships will sail many centuries later, filled with a few intrepid pioneers headed for the next unsettled systems, if there are any left in the neighborhood. They will leave behind a thriving colony with every intention to stay and fill their new (or, for them, home) system to the brim, in good time. Fill it such that every planet, every asteroid, and probably even much empty space is inhabited and/or littered with artifacts. Similar to what we are doing right here on Earth, and hard to miss even upon cursory inspection.

Ron S: “How many ‘petabytes’ have we not or not yet collected?”

How many times do you have to look in your garage to be convinced there’s no car there? We have already collected petabytes of data on other galaxies. Past tense. With many more soon to come.

“Are the ones we do have appropriate to evaluate the hypothesis.”

You could start the ball rolling by telling us what your testable hypothesis is. The speculation that therre exist trillions of alien civilizations in those hundreds of billions of galaxies, but every last one of them stays huddled and hidden on their planet of origin, is not a testable hypothesis. And it’s also highly implausible on other grounds, besides lack of falsifiability.

On the other hand, the hypothesis that no civilization exists in those galaxies, that has converted a significant fraction of the reflecting surfaces and/or radiation emissions of its galaxy (like we are doing to earth and even more to the spacecraft we have launched) to efficient and thus highly detectable forms, is a very testable hypothesis with today’s data and technology.

Nick,

Your hypothesis, by your criteria, is wrong. Fine. If so, we now know that ETI, if it exists, may not behave in the manner you describe. That tells us nothing about other hypotheses that might be correct.

I am not proposing a hypothesis and so I have nothing to defend. What I am doing is pointing out that we have little data to support the vast number of possible hypotheses about ETI and how they actually behave (not some peculiar assumption we might invent about them).

In that light your so-called “petabytes” of data mean little. You appear to have completely missed my point that volume of data is unimpressive if it is a tiny fraction of the search space. Until then it is premature to declare any extant or prospective hypothesis false which requires a more-complete sampling of the search space. Conclusions are premature when the data do not warrant those conclusions.

So, now we know that there are no highly detectable civilizations out there. This leaves only two options: there are none, or of all the ones there are, not one is highly detectable. Neither of these answers is very satisfying. That is what the Fermi ‘paradox’ is all about. My money is on ‘none’.

I agree with Eniac’s last comment, but feel that it did not sufficiently emphasise nicks new perspective. The Fermi paradox points out the extreme difficulty for those that want to hypothesise that the number of alien civilisations in the history of the Milky Way has been much larger than zero. Nick extends this by showing that there may also be difficulties in postulating that the number of ETI’s per million galaxies is greater than a handful.

Rob, you are right that Nick extends the argument quite a bit by postulating that life would have an observable (for us) effect on other galaxies. I am not sure I see the inevitability of this, but it is certainly an interesting thought.

However, I submit Fermi does not require “much larger than zero”, only “larger than zero”. This is because of the argument I have been trying to make many times, and I believe Fermi had in mind as well: If there were spacefaring aliens, even just one instance, they would be all over the galaxy. Including right here. Or, if you will, we would be them. This, we know, is not the case. But, if all goes well, we will be one day.