It’s always gratifying to note the contributions of amateur astronomers to front-line science. In the case of three small planets discovered around the Kepler star KOI-961, the kudos go to Kevin Apps, now a co-author of a paper on the new work. It was Apps who put postdoc Philip Muirhead (Caltech) on to the idea that KOI-961, a red dwarf, was quite similar to another red dwarf, the well-characterized Barnard’s Star, some six light years away in the constellation Ophiuchus. It was a useful idea, because we do have accurate estimates of Barnard Star’s size, and the size of the star becomes a key factor in exoplanet detections.

For the depth of a light curve — the dimming of the star over time due to the passage of planets across its surface as seen from Kepler — reveals the size of the respective planets. Researchers from Vanderbilt University aided the Caltech team in determining KOI-961’s size, a difficult call because while Kepler offers data about a star’s diameter, that data is considered unreliable for red dwarfs. Detailed spectra from both Palomar and Keck showed that Kevin Apps was right. “When we compared its fingerprint with those of the best known M dwarfs we found that Barnard’s Star was the best match,” says Vanderbilt astronomer Keivan Stassun.

Having established the size, mass and luminosity of KOI-961, the team could calculate the size and characteristics of the planets around it. Confirming three planets that are actually smaller than Earth took intensive follow-up, using photographs taken with the Palomar Observatory’s Samuel Oschin Telescope in 1951. KOI-961 is in Cygnus about 130 light years away, close enough to show motion in the time period involved, and it was clear from studying the photographs that no background stars could have accounted for the light curves.

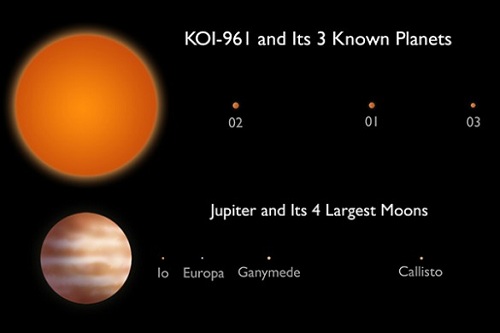

We wind up with three small exoplanets that range in size from 0.57 to 0.78 times the radius of Earth. The primary is only about 70 percent bigger than Jupiter, but all three of the planets are so close to it that their temperatures are expected to range from 200 degrees Celsius for the outermost planet up to 500 degrees Celsius for the innermost. The entire system is small enough that Caltech astronomer John Johnson compares it to Jupiter and its moons, adding “This is causing me to have to fully recalibrate my notion of planetary and stellar systems.”

Image: This artist’s conception compares the KOI-961 planetary system to Jupiter and the largest four of its moons. The KOI-961 system hosts the three smallest planets known to orbit a star beyond our sun (called KOI-961.01, KOI-961.02 and KOI-961.03). The planet and moon orbits are drawn to the same scale. The sizes of the stars, planets and moons have been increased for visibility. Credit: Caltech.

All three planets are thought to be rocky, so small that only such a composition would allow them to hold together. And while the three are obviously not habitable, the fact that we’re now finding small worlds around red dwarfs has undeniable implications. Johnson again:

“Red dwarfs make up eight out of every ten stars in the galaxy. That boosts the chances of other life being in the universe—that’s the ultimate result here. If these planets are as common as they appear—and because red dwarfs themselves are so common—then the whole galaxy must be just swarming with little habitable planets around faint red dwarfs.”

After all, while Kepler reported 900 exoplanet candidates in February, only 85 or so were in red dwarf systems, a small sample but one that is already producing planets. The vast numbers of red dwarfs in the Milky Way thus gain further interest as possible sites for life, although as we’ve discussed many times in these pages, huge issues remain, such as tidal locking and the flare activity often found in younger red dwarfs. We can expect continuing study of the question of whether a rocky world in the habitable zone of such a star could offer life a viable foothold.

Ongoing red dwarf studies will add to our picture of the prevalence of such planets, as the paper on this work notes:

Combined with the low probability of a planetary system being geometrically aligned such that a transit is observed (only 13% in the case of KOI 961.01), Kepler’s discovery of planets around KOI 961 could be an indication that planets are common around mid-to-late M dwarfs, or at least not rare. This would be consistent with the results of Howard et al. (2011), who used the Kepler detections to show that the frequency of sub-Neptune-size planets (RP = 2-4 R?) increases with decreasing stellar e?ective temperature for stars earlier than M0. Results from on-going exoplanet surveys of M dwarfs such as MEarth (e.g. Irwin et al. 2011b), and future programs such as the Habitable Zone Planet Finder (e.g. Mahadevan et al. 2010; Ramsey et al. 2008) and CARMENES (Quirrenbach et al. 2010), will shed light on the statistics of low-mass planets around mid and later M dwarfs.

And what of Barnard’s Star itself? This Vanderbilt news release discusses the star’s appearance in televised science fiction but misses the wonderful use Robert Forward made of it in Rocheworld, a novel he wrote to illustrate his concept of ‘staged’ laser sails carrying a manned mission to the stars. In any case, the idea of planets around Barnard’s Star is not new. It was in the late 1960s that Peter van de Kamp announced what he thought were two gas giants in orbit around the star, but neither planet could be confirmed and the detection is now thought to have been the result of a systematic error produced by van de Kamp’s equipment.

Nonetheless, while we’ve been able to exclude planets larger than about five Earth masses within 1.8 AU of the star, Barnard’s Star could still have smaller undetected planets. Doubtless the steadily growing interest in red dwarfs will result in further studies of this nearby target.

The paper is Muirhead et al., “Characterizing the Cool KOIs III. KOI-961: A Small Star with Large Proper Motion and Three Small Planets,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (abstract).

I’d like to see these worlds modeled in detail. Take the outermost one with Rp/Re 0.57 and Teq 450K. Very likely to be tidally locked, so Teq is likely an upper bound encountered near the subsolar point. From earlier models by Joshi, et al the poles and terminator could be more temperate. The nature of the atmosphere would be a major factor.

Barnard’s Star and KOI-961 are both low-mass, low-metallicity stars, as opposed to the typical hosts for gas giant planets. It is certainly interesting to see the results of planet formation in such an environment.

A great amount of exoplanet news these last few days. More circumbinary planets identified, small rocky worlds discovered around an M-dwarf and a micro-lensing survey supporting the theory of the ubiquity of planets. And more results expected from the Kepler science team. I would hope that Barnard’s Star and other nearby M-dwarfs will be the observing list of the APF and HARPs North.

It sure looks to me as if there are an awful lot of stages set for life. Now if only we knew more about biogenesis.

Here’s the problem. Planets like this could be present around many, or even most, close-by (<10pc) M dwarfs – even in the Hz. How do we winkle them out? The reflex RV will probably be too small even for sensitive searches like HARPS, these planets seem to be outside GAIA's discovery space, so unless they transit (pretty small chance of transit in such a small sample, and even then the signals will be tiny, requiring one of the new phase A explorer proposals – TESS perhaps) they are going to be elusive.

What's the solution? Am I too pessimistic?

P

To Phil, TESS is designed to search for transits. The new ground-based RV searches may be able to detect these planets thanks to their short periods even if they’re located in the HZ. But this will require many observations.

It will take time. And the target M-dwarfs have to be bright enough (close enough) for mid-size telescopes. Like APF and HARPS North and South.

I wish SIM had been completed. It would have been very good for the nearby stars.

Continuing an important discussion from the prior thread:

“FrankH January 12, 2012 at 16:23

@jkittle – This online calculator lets you calculate the gas retention for any planet:

http://astro.unl.edu/naap/atmosphere/animations/gasRetentionPlot.html”

Well, yes and no. Planetary atmospheres defy simple modeling. The wonderful application from U of N@L models the thermal escape mechanism only, and only for molecules. Looking at the plot, one is stunned to discover that Mars should be better able to retain N2 than Titan! Hmmm. Obviously there is more to atmospheric retention than mass and temperature.

One answer is that we don’t know what the original volatile inventory of Mars (or Earth) was. Mars might have started out as gas poor. Also, there is a theory of atmospheric loss due to impact erosion. Maybe with an escape velocity of only 5 km/sec, Mars actually lost atmosphere in the late heavy bombardment?

If a planet doesn’t have a decent magnetic field, there is atmospheric loss due to the stellar wind, likely the real problem with Mars. Please note, if a star emits ionizing radiation, the exosphere will be populated with ions. So the operative question is not the escape loss of H2O, but the loss rate of H+. Enough of that will dehydrate a planet. Also of note, cooler stars might be less of a problem for ionization loss than a UV emitting G2 like Sol.

Finally, there is the matter of atmospheric structure. On Earth, there is water vapor at the warm surface. However, the atmosphere from 10-20km is circa minus 55C. This keeps the stratosphere (and exosphere) pretty dry. This is a good thing, as Earth is not massive enough to retain H+ in the exosphere. If the Earth warms enough that water vapor can mix into the exosphere, goodbye oceans, same as on Venus.

Anyway, in the spirit of the original question, how would small Earth twins (same density, same magnetic field strength, same oceans, same atmospheric composition and structure) fare in Earth’s orbit around Sol? The preliminary answer: The planets with 0.78 and 0.57 Earth radii should be fine.

The final answer is again more complicated. Remember no magnetic field no atmospheric protection. What are the odds that a planet 0.57 Earth radius (18.5% Earth mass) would still have a robust magnetic field when it is over 4 gigayears old? Very low. On the other hand the 0.78 Earth radius planet would mass 47.5% of Earth mass and might retain a working magnetic dynamo for the life of the system. My guess is that is about the lower limit for Earth twins.

Totally forgot about SIM! Yes, that’s a loss.

Here’s hoping for slow steady progress from the other efforts you mentioned.

P

Mike,

Barnard’s star is only 5 or so degrees north of the celestial equator so it can and has been a target of the European team using the HARPS spectrometer in Chile.

This is very encouraging news! The ubiquity of red dwarfs combined with planet-bearing potential is promising. Also, the fact that we’re finding small planets in itself means that we’re closing in on exo-earths.

As far as recalibrating stellar and planetary systems – the universe is a messy place. A very consistent trend has been its tendency to defy tidy categorizations. As we research further, structures and objects become more complex with more gray areas. Though this may seem daunting, ultimately it makes for a more fascinating universe to live in. It may also help in the exoplanet hunt – the “holy grail” of a second earth may be in a very different kind of solar system from our own.

Today’s arXiv haul contained a paper suggesting that a much smaller planet may have been detected via its evaporation. Actually pinning down the properties of the planet (if it is indeed a planet) may be quite tricky: we can only see the tail of material ejected from the planet, not the planet itself.

Possible Disintegrating Short-Period Super-Mercury Orbiting KIC 12557548

I was also going to criticise the atmospheric loss calculator linked by FrankH on the previous thread, but Joy beat me too it. I would, however, like to add the following.

Thermal loss is all that is relatively easy to model, but even that there are temperature differences with height (also mentioned by Joy) that provide an annoying complication. In an atmosphere with no vertical air movements and no uv light photolysing molecules, then we should effectively have permanent retention with an escape velocity 6 times average molecular velocity, and slow loss of an unreplenished atmosphere over a hundred million years at 5 times this figure. That calculator used 10 times this as a fair figure to model a more complex world. This seems like a great compromise (especially for diatomic atmospheric molecules), but I think that we should keep in mind that under what looks like very unusual circumstances (as judged by current data from our Sol system), a much smaller world than it indicates can retain an atmosphere that is warm at ground level.

Everyone seems to already know that under some other sets of unusual circumstances, a much larger world than indicated by this formula will have no retained atmosphere, due to other types of atmospheric escape.

Thank You Rob Henry x

One more thing to add. Although Venus is nearly Earth mass and same age, she has no dynamo. Our understanding of even how Earth’s dynamo works is very preliminary, so the various tentative hypotheses about why Venus lacks one are little more than educated guesses.

Still, it is reasonable to think that having a planetary rotation rate measured in hours rather than months is an issue in having a working dynamo. (Put another way, the Earth rotates at the equatorial surface at supersonic speed, Venus rotates at walking speed). Having a moon massive enough to raise decent tides may also help. (Mars has a decent rotation rate, but the dynamo has shut down even though there seems to have been recent volcanism. Why? The lack of plate tectonics to drive mantle convection?)

So for a mini Earth to retain atmosphere, I would guess that it should also not be tidally locked at a minimum, have mass greater than Mars (how much greater?), and might need a massive moon to stir the dynamo as well.

Joy & Rob – The atmospheric loss calculator provides a MINIMUM size for a planet at a given temp. Other factors will only make the atmospheric loss greater, but the primary factor will be the escape velocity and atmospheric temperature. You can heat up the atmosphere by many methods (lack of a magnetic field causes heating & erosion due to stellar winds, etc.) but the basic physics will always stay the same.

I agree – a planet much smaller than 0.75 Earth will have a hard time staying habitable for gigayears in a star’s HZ.

It would have been interesting if our solar system had swapped the positions of Mars and Venus; the new Mars would be a hot, airless world – a big Mercury – and the new Venus would be a cold, but probably habitable world.

Speaking of the Barnard’s star connection, I know that a planet was suspected to exist in orbit around this “nearby” red dwarf. In fact, if I remember correctly, the suspected planet was of the jovian-type, but more recent analyses suggest that there are no large planets around this star.

My question is this: would a system akin to the KOI-961 system of sub-earth sized planets be detectable with current technology around Barnard’s star, or, for that matter any of the other close by red dwarfs?

Joy: About the idea that planetary magnetic fields slow atmosphere loss.

Can you point me to a discussion of why that seems to be widely believed? The fact that Venus has no magnetic field yet has has at least 3x the nitrogen that Earth has is a point against the idea that the magnetic field matters for atmosphere loss.

@Joy:

I’ll point out the examples of Mercury (rotation period 58.6 days, mass 0.055 times Earth) and Ganymede (tidally locked, rotation period 7.15 days, mass 0.025 times Earth), both of which maintain intrinsic geomagnetic fields.

FrankH, I am hyperaware that that atmospheric calculator is MEANT to be a minimum. That over simplistic approach is what worries me. Allow me a hint that things could be otherwise.

Until more recent data, some scientists hoped that Titan might be warm enough at the base of its methane loaded atmosphere for liquid water to exist. Plug those temperatures into that calculator, and that would seem delusional, yet I assure it was not. Atmospheres can loose enough heat with height, such that we could not have ruled that out until then.

That calculator can give a good ballpark minimum for atmospheric retention, but I am keen to construe that atmospheres are so complex in structure (as outlined by Joy) that there is a danger inherent in overplaying such simple models.

And yes swapping Venus an Mars also appeal to me as an interesting theoretical exercise. In particular would oceanic retention mean that Venus also experienced drifting continents, or is its different method of the dispersal of internally generated heat more fundamental, and how would that effect feedback to its temperature control?

Andy, as I’m sure you know, current theories of magnetic field generation seem to map very poorly to the available data. From what I’ve read, Joy is right in pointing our that a rapid rate of rotation may be important in field generation. If you know of any peer reviewed paper anywhere on how a slowly spinning planet (especially one with a solid interior) can have a powerful magnetic field I would love a reference to it. If not I think that Joy is absolutely correct in highlighting that this could be a potential problem, and she is similarly correct in calling that a guess.

Jim Baerg, Venus has such a massive atmosphere that it would take a long time for the solar wind to strip it all, but the question as to why theoreticians have such confidence that their models are correct is a great one. I suspect I know the answer but beware that the following is just a guess.

The solar wind does not just strip the atmosphere, it also dumps much hydrogen and helium in it. We can easily calculate the rate helium is dumped there annually and the amount in its atmosphere, and if their models were incorrect of how these high speed particles interacted with the atmosphere these would be discordant from theory by orders of magnitude.

Solid interior? Magnetic field generated in the iron layer would probably impossible due to the temperatures exceeding the Curie temperature. Whether you could still do interesting things with deep saltwater oceans is another matter… (hmm… I wonder what kind of induced field you’d get if you hit a non-magnetic ocean-bearing planet with a solar flare?)

There are quite a few theoretical papers out there on the question of magnetic field generation in terrestrial planets: some predict significant effects from rotation, others seem to suggest it may be less of an important effect. I agree that Venus is an extremely interesting example, though I don’t think we yet know enough about what’s going on deep inside the planet (particularly with regard to thermal/density gradients to drive convection) to put the blame entirely on the slow rotation. Unfortunately I doubt we will be seeing a network of seismometers on that planet to pin down the interior structure any time soon, for a whole variety of good reasons.

@Jim Baerg – There have been some articles claiming that Mars has lost up to 1/3 of its atmosphere due to interactions with the solar wind. The solar wind dumps energy into the upper atmosphere, heating it. If the planet already has a tenuous (pun intended) grasp on its atmosphere, the extra energy increases the average velocity of the atmosphere, and some will reach escape velocity.

The average velocity of the the gases currently in Venus’ atmosphere are not close to its escape velocity, so the solar wind has a smaller effect. When Venus lost its water, the water vapor was probably disassociated by the Sun and the hydrogen (and some O2) were able to escape. The solar wind may have helped in this case.

@Rob Henry

The atmosphere calculator just tells you that given a density and radius (and therefore an escape velocity) the gases indicated will or will not be retained.

That’s it.

It makes no assumptions about initial conditions, history, external factors etc. Just basic physics. Useful for showing that Mars, for instance, would not be able to retain a dense Earth-like condition for very long, especially if it was warmer. Or that a large gas giant moon like Titan would quickly (and permanently) loose its atmosphere if warmed to Earth-like temperature.

Regarding atmospheric escape, the relevant temperature is the temperature in the upper atmosphere (especially the exosphere), and this is not a simple function of distance from the Sun.

Here are some comparisons

If you look at the exobase temperatures, it is striking that Earth has extremely high temperatures at the exobase compared to Mars and Venus. IIRC this is because the oxygen/nitrogen dominated atmosphere is more efficient at absorbing solar ultraviolet than the atmospheres of Mars or Venus, but would have to confirm this…

No FrankH, that atmospheric calculator that you linked does not rely on basic physics. Basic is using the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution for an idealised gas on an atmosphere that can escape directly from the surface (or one of uniform temperature). As I have already stated that results in effectively permanent retention if escape velocities are more that 6X average molecular velocity. Perhaps you are aware of a simple construct whereby the 10X figure they use comes from, but I suspect that it is just a guestimate derived of what we know of our Sol system.

Andy, you made be wonder about something I never thought of before. Is there any way of temporally inducing a powerful magnetic field in the outer layers of a world that is so small that its inner iron core rapidly cools through its Curie temperature? Until this moment I had actually thought that a solid core would only allow a small field!

@Rob Henry: really I am not sure here, the reason I suggested it is that there are several icy moons which exhibit induced magnetic fields as they move through the magnetic field of their parent planets. This is taken as evidence for a conducting layer within these moons, probably a saltwater ocean. Could this work on a non-magnetic Earth? I have no idea.

The question of what happens on a non-magnetic planet even has relevance to the Earth: after all, the Sun is unlikely to be considerate enough to shut down its activity while the Earth undergoes a geomagnetic reversal.

@Rob Henry from their description page:

“Note that for each gas a region of the speed-temperature parameter space is colored where the gas would be totally retained by the body to a dashed line at 10×vavg. This coloring slowly faces out to 6×vavg.”

and:

“If a body has an escape velocity vesc over 10×vavg of a gas, it will certainly

retain that gas over time intervals on the order of the age of our solar

system.

If vesc is roughly 5 to 9 times vavg, the gas will be partially retained and the

color fades into white over this parameter range.

If vesc < 5 vavg, the gas will escape into space quickly. "

They also mention that the temperature of the outer atmosphere (where the escape ultimately happens) is what's really important. Considering that they had to make simplifications, it's still a great simulator and clearly shows that there would be no way for a planet like Mars (or a moon like Titan) to retain a thick, Earth-like atmosphere for billions of years at Earth-like temps.

FrankH, thanks for pointing out the description page. Sorry, I should have read it. However that just makes it even more mysterious since that rapid loss per few-million-year scale time boundary at 5X escape velocity comes straight from the simple ideal gas model that I mentioned above, yet that very same model gives an intermediate ability at atmospheric retention at 5X – 6X, yet they state 5X – 9X. Perhaps their model is composite?