by Larry Klaes

Larry Klaes is a long-time Centauri Dreams contributor, a practitioner of the Tau Zero Foundation and a serious devotee of space exploration and its history. Here he gives us a look at the Pioneer probes that first took us to the outer Solar System, journeys that foreshadowed the later exploits of the Voyagers and the more recent New Horizons mission to Pluto/Charon. It’s hard to believe that it’s been fully forty years since the Pioneers were launched. They came out of the era when thinking big was the order of the day, Apollo was putting astronauts on the Moon and human expansion into the cosmos seemed inevitable. When we ponder today’s budget shortfalls and drifting public attention, it’s heartening to recall that era even as we speculate about missions that will follow up on the findings of these two remarkable probes.

The early 1970s was an exciting time for lunar and planetary exploration. On the Moon, Apollo was still placing pairs of astronauts on Earth’s natural satellite to collect hundreds of pounds of lunar surface material and other priceless data. The Soviet Union was conducting a quite successful automated survey of the Moon with their two Lunakhod rovers and returning small but still valuable samples with their Luna series of landers.

The United States Mariner 9 and the Soviet Mars 2 and 3 probes were circling the Red Planet, returning the first in-depth images and data about that world which showed that Mars was not the dead and merely cratered realm that earlier flyby missions with their limited coverage had led scientists to believe. There was also excitement about an upcoming mission named Viking to place two robot landers on Mars to search for life there.

Closer to the Sun, the Soviets had finally succeeded in landing intact and functioning on the hellish world of Venus with their Venera probes. America was preparing a probe named Mariner 10 that would not only flyby Venus and return the first close-up images of its thick and cloudy atmosphere, but proceed on to Mercury and reveal what that little world really looked like.

The outer solar system had not been neglected in NASA’s plans for deep space exploration. The agency was preparing a modified version of its original Grand Tour plan, which would have sent two nuclear-powered probes past every world from Jupiter to Pluto in the summer of 1977.

No human vessel had ever visited the celestial realm where the gas giant planets dominated, or even crossed the Planetoid Belt which lay between the small and rocky terrestrial worlds of the inner solar system and the Jovian behemoths. Space engineers and officials realized they needed a precursor mission to pave the way for the success of these later more sophisticated machines. Two aptly named craft called Pioneer – coming from a long line of automated explorers going back to the earliest days of the Space Age – were designed and built for this task.

Image: Launch of Pioneer 10. Credit: NASA.

Pioneer F and G, which would receive the respective numbers 10 and 11 once they had been successfully launched on their missions, were hardy little vessels dominated by large parabolic high-gain radio dish antenna for communicating with an Earth that would eventually be hundreds of millions of miles away. Their computer “brains” were quite simple as dictated by the technology of the day, the size of the probes, and their working environment. Pioneer 10 and 11 would be kept functioning for at least several years by four RTGs attached to long booms on the probes, necessitated by the decreasing radiant energy of the distant Sun. Eleven scientific instruments were chosen for the mission.

Pioneers’ primary tasks were to do a Jupiter flyby and return images and data on the planet’s atmosphere while also attempting to glean clues about its deep and mysterious interior. Unlike the terrestrial worlds, which generally consist of a relatively thin layer of air over a rocky crust which in turn covered layers of molten and solid iron along with other minerals, the Jovian globes were primarily all atmosphere, though it was speculated that as one descended towards Jupiter’s core, the incredible pressures created some very strange physics with the surrounding gases. In any case, there was no actual surface such as human beings were accustomed to on Earth.

The Pioneers would also examine in situ the vast Jovian magnetosphere, whose intense cracklings could be picked up by radio astronomers on Earth and was presumed to be home to very lethal amounts of radiation. Project team members would even try to image and refine the masses of some of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons if possible. Although known to humanity since at least 1610, the worlds of Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto were little better than points of light with a few indistinct smudges seen on them after almost four centuries of telescopic examination by astronomers.

When the time came for Pioneer 10 and 11 to make their daring plunges past Jupiter, an interesting consequence would happen: The massive bulk of that alien world combined with their already high rates of acceleration would create for the little explorers what is known as a slingshot effect. The Pioneers would be given just enough kinetic energy from Jupiter to eventually escape the gravitational pull of the whole Sol system and become the first human-made objects to enter interstellar space. In a sense, Pioneer 10 and 11 would become our species first representatives in the Milky Way.

The Pioneer team and NASA Ames acknowledged this fact but made no particularly lavish public note about this rather remarkable landmark in space history. After all, the probes were not expected to last in terms of returning data much after their Jovian encounters. Even though they were the fastest vessels yet sent by humanity into space, they were not aimed at any particular star and would still take tens of thousands of years just to reach the distance to the nearest system, Alpha Centauri. Besides, in a galaxy composed of roughly 400 billion star systems over 100,000 light years across, what were the chances that anyone would ever be able to find or notice two inert specks of metal and wiring drifting aimlessly through deep space?

“A Special Message from Mankind”

In 1971, a group of science correspondents from the national press were invited by NASA to visit TRW Systems in California, where Pioneer 10 was undergoing tests in a giant simulator which reproduced the harsh conditions that both of the robot explorers would encounter beyond Earth.

One of the reporters present that day had an epiphany about the Pioneers’ post-Jupiter mission as he looked at the silvery probe through the simulator portholes. To quote from the Epilog of the official NASA Publication on the probes, Pioneer Odyssey (SP-396, Revised Edition, 1977):

“Eric Burgess, then with The Christian Science Monitor, visualized the passage of Pioneer 10 beyond the Solar System as mankind’s first emissary to the stars. This spacecraft should carry a special message from mankind, he thought, a message that would tell any finder of the spacecraft a million or even a billion years hence that planet Earth had evolved an intelligent species that could think beyond its own time and beyond its own Solar System.”

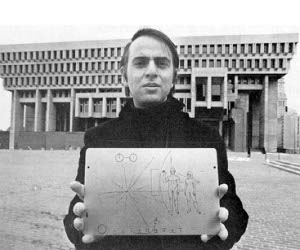

Burgess presented his idea to two fellow correspondents, Don Bane and Richard Hoagland (yes, *that* Richard Hoagland), who “enthusiastically agreed” with Burgess. They in turn sought out a scientist named Carl Sagan, who was at the nearby Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena involved with the Mariner 9 mission to Mars.

A longtime advocate of extraterrestrial life, Sagan was as enthusiastic about this message to ETI as the correspondents were. Upon requesting and receiving permission (somewhat surprisingly) from NASA to go ahead with this plan, Sagan and his colleague at Cornell University, Dr. Frank Drake of SETI Project Ozma fame, put together a message on a golden plaque that was small only in its relative physical size. Everything else about what would become known as the Pioneer Plaque was as large and as vast as its potential ramifications for humanity’s future expansion into the Cosmos.

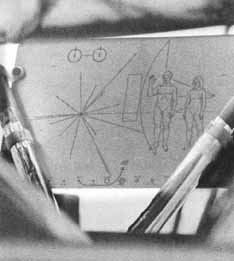

At six by nine inches in diameter and just 0.050 inch thick, the Pioneer Plaque was similar in size to a very thin hardcover book. Unlike the vast majority of terrestrial books, however, this one could not be inscribed with any standard human language, for its intended recipients were not expected to know any Earthly tongue or even its planet of origin. Instead, the plaque designers would use the hopefully universal language of science. After all, the Pioneer probes would only be found by someone with the capability for interstellar travel, as the probes will probably never pass through any star systems in the Milky Way galaxy during their incredibly long celestial journeys.

The messages on the plaque were direct and confined in quantity: To explain the purpose of the probes’ mission, to show where they came from, and who built and launched them into the galactic neighborhood.

The mission purpose was depicted by a basic diagram of our Sol system from our yellow dwarf star to Pluto (the first members of the Kuiper Belt after Pluto would not be discovered until 1992). Saturn got a thin line to represent its impressive ring system: The less prominent rings of the three other Jovian worlds had yet to be known. Using an arrow-tipped line, the Pioneer probe was shown moving from the third small circle (Earth) to between and past Jupiter and Saturn, its antenna pointing back at its place of origin. The various sizes of the planets in our Sol system were stated in binary notation.

So that the recipients could have a chance at understanding the measurements on the plaque, Sagan and Drake made a small representation of the “hyperfine transition of neutral atomic hydrogen.” With hydrogen being the most abundant element throughout the Universe, the engraved image allows the finders of the plaque a way to comprehend both time and physical length.

Between the hydrogen atom and the Sol system depictions was a radial pattern of fifteen lines with binary tick marks on them. These are the distances and rotation rates of pulsars, rapidly rotating neutron stars that have been called galactic beacons by some astronomers. The plaque creators felt that, working with the limited canvas they had along with where and how the probes will most likely be found, this was the best way to show those who come upon the Pioneer probes where their makers came from both in space and time, as the spinning rates of pulsars do slow down.

“The Most Mysterious Part of the Message”

Of all the items to be engraved on the Pioneer Plaque, nothing would draw the most attention and commentary as the two human figures representing our species to the presumed recipients. Drawn by artist Linda Salzman Sagan, who also happened to be Carl’s second wife at the time, the human male and female were considered by Sagan to be “the most mysterious part of the message” as he wrote about them in his 1973 book The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective. It was thought that whoever found the Pioneers would not only have to be more advanced than their makers, but also bear little resemblance to our species, as the future discoverers were presumed to originate from and evolve in the seas of another and quite different world from ours.

Of course it was also possible – and in fact rather more likely by comparison – that one or both of the Pioneer probes might be recovered not by an ETI but by the descendants of humanity from Earth, who may find themselves spread throughout the Milky Way galaxy in distant epochs. Certainly some of our future children might be interested in recovering a rare relic from among the earliest days of humanity’s Space Age, which has been estimated to remain intact for at least one billion years in interstellar space.

It is also conceivable that the human descendants who could find the Pioneers may no longer resemble the men and women who built and launched the probes way back in the late Twentieth Century, having undergone biological and technological changes through genetic engineering to suit such situations as adaptation to alien environments and cultural aesthetics. There is also the possibility that the terran intelligences which finally enter the wider galaxy may have come solely from our technological developments, in which case they would bear almost no resemblance to their creators at all.

If nothing else, the Pioneers and their plaques certainly deserve a better fate than the one given in the sub-par 1989 film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, where a Klingon warship comes upon the long-inactive Pioneer 10 tumbling through the inky void. The ship’s commander considers the Earth probe to be little more than space junk and uses the relic for some target practice, subsequently turning it and the plaque into little pieces of metal.

The two figures on the Pioneer plaque were drawn to be “pan-racial”; this meant that the artist tried to incorporate the physical features of three of the major human races onto her creations. Both were rendered without any clothing and with the male raising his right arm in what would hopefully be interpreted as a form of friendly greeting. To give the recipients an idea as to how big Pioneer’s builders were, a schematic representation of the probe was placed behind the humans, along with a binary mark on the far right to further indicate the height of the woman.

As Sagan would document in The Cosmic Connection, the reactions to the plaque and especially the nude human representations from the bipedal inhabitants of the third planet from Sol were wide, varied, and anything but tepid. While many responses were very positive from folks who understood and appreciated the significance of what was being attempted with the plaque, others had what could best be described as rather parochial and puritanical comments on this interstellar message.

Most of the people in this second category were upset that the human representations were not only not wearing any clothing, but were subsequently displaying their genitalia – though in the case of the female, this was not entirely true. Even the plaque makers deferred to modesty when it came to that feature in order to ensure that the plaque made it onto the probe at all. A subjective form of moral decency may have been preserved, but the result may one day be further confusion about our species for those who lay their appendages and senses upon the plaque in some undetermined future.

Other plaque complaints included the presumed absence of a particular race for the humans, the seeming passivity of the female, and the symbolic lack of any deities or their religions. Some voiced the concern that would be heard for virtually all such subsequent METI (Messaging to Extraterrestrial Intelligence) efforts: The pulsar diagram and representation of our star system would allow and even invite a hostile ETI to become aware of humanity and know where to find us in order to commit subjugation or even extermination.

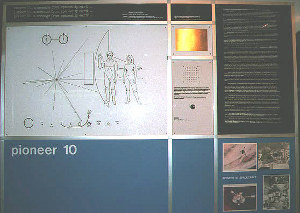

Image: The Pioneer exhibit at the Boston Museum of Science, which appeared there from 1973 to 1999. Credit: Donald Bellunduno.

Whether or not there are such dangerous beings in the galaxy, one thing is certain: The physical parameters of the Pioneer probes, which in one regard hamper their detection by just about any ETI, are also their saving grace should such sufficient intelligent dangers exist in the Milky Way. For though the nearly identical vessels will survive for eons in the interstellar void and cover many light years of space during their existences, their small dimensions and a lack of power and signaling activity will also make these probes quite difficult to detect, especially for anyone who is unaware of them in the first place.

Even if the Pioneers are found by an alien species one day, there are also the intellectual hurdles to overcome of the recipient species first noticing the plaque attached to the probe and then understanding its messages. Perhaps these presumed obstacles will be all too obvious and easy to beings that can ply the stars and capture long inactive probes drifting in the cold and dark of deep space, but their minds will almost certainly be alien to ours in many key respects: They may come to certain conclusions about our mechanical “ambassador” and its engraved message which would surprise and perhaps even shock us. Sagan even covered that possibility in The Cosmic Connection with a reprint of some imagined alien reactions from the English humor magazine Punch.

As with the first METI transmitted from the Arecibo Radio Observatory in Puerto Rico several years after the launches of Pioneer 10 and 11 – and which, moving at light speed, would rapidly outpace the robotic explorers – the Pioneer plaques were largely a symbolic gesture, a scientific commemoration of a major achievement in human history. The authors of Pioneer Odyssey – among them Eric Burgess – called the plaques “interstellar/intellectual cave paintings.” Anything else that the plaques would inspire and affect from their present into the far future was considered a bonus.

Once the design was completed and approved, the diagrams were engraved onto a rectangular aluminum plate anodized with gold. The plaque was then bolted onto the antenna struts of the Pioneer with the engraved side facing inward towards the main body of the probe to better protect it from erosion by cosmic dust particles.

Image: Carl Sagan holding a copy of the plaque while standing in front of the Boston Town Hall circa 1973.

A much-too-late thought: Would it have been possible to engrave *both* sides of the plaque with the messages? This could have at least improved the chances for the information to survive in interstellar space until found. Having the message facing away from the craft as well as inward in the direction of any external observers would also increase the likelihood of the plaque being noticed as an item of particular interest addressed directly to the discoverers. In any event, the plaque is there aboard both Pioneers traveling with them into the Milky Way and that is what matters.

The First Firsts

Pioneer 10 was finally lofted into space aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket from Cape Kennedy in Florida on the evening of March 2, 1972. Just minutes later, Pioneer was moving at a velocity of 32,114 miles per hour, over seven thousand miles per hour faster than any spacecraft before it. Eleven hours later, Pioneer 10 passed the orbit of Earth’s Moon, the same distance which took the manned Apollo missions three whole days to reach. The robotic explorer also became the first NASA spacecraft to operate solely on nuclear electric power, a critical component for future deep space vessels.

Four months after launch, Pioneer 10 became the first probe to fly through the Planetoid Belt between Mars and Jupiter. Despite some concerns about the craft being struck and destroyed by an errant particle in that region of space, Pioneer 10 emerged from the belt in February of 1973 unharmed, effectively removing a perceived barrier to space flight beyond the terrestrial worlds of the Sol system.

Pioneer 10 finally encountered the king of the planets in early December of 1973, returning the first close-up images of Jupiter and some of its Galilean moons and other data while being slung by the incredible mass of the planet itself to 82,000 miles per hour, enough to send the probe on its way out of the Sol system.

Thanks to Pioneer 10 and its sister probe, Pioneer 11, which became the second visitor to the Jovian world one year later and then the first vessel to Saturn in 1979, scientists learned much about these two planets and some of their moons. This was important not only for our understanding of the neighboring gas giants themselves, but for the exoworlds that would be discovered circling other suns in the coming decades. Most of the alien planets we know bear at least some similarities to Jupiter and Saturn in both size and composition. The Pioneers gave us our first look at the kind of realms that their remote mechanical descendants will encounter when the first true interstellar explorers arrive at their destinations.

Exceeding Expectations and Distance

The team that built and controlled Pioneer 10 expected the probe to stop transmitting to Earth not long after it crossed the orbit of the planet Uranus in 1980. Instead both Pioneers continued to be of service to science long after their predicted expiration dates, thanks to their design and the RTGs they derived power from to operate. Among their important achievements was the monitoring of the outer Sol system where, to quote the opening lines from a certain science fiction television series, literally no one had gone before. Among their discoveries was that the solar wind extends far beyond the boundaries of the main planets of our Sol system, much more distant than originally thought.

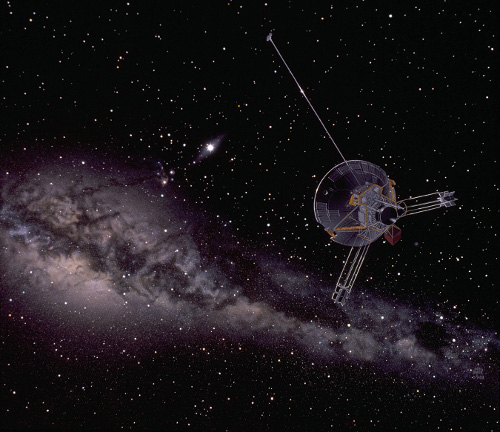

Image: Pioneer 10 enroute. Credit: Don Davis.

Pioneer 10 even assisted the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) effort by serving as a favorite test subject for The SETI Institute’s Project Phoenix in the mid-1990s. Utilizing NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) of giant radio telescopes scattered across the globe, that team was able to detect the probe’s very faint signal from billions of miles across space. Pioneer 10 gave The SETI Institute confidence that they could detect and interpret an artificial extraterrestrial signal, even a weak transmission buried among the natural noise of the Cosmos.

Eventually the power levels in the RTGs of the Pioneers fell to the point that the mission controllers could no longer conserve enough energy among the remaining operating instruments to keep the probes communicating with Earth. Pioneer 11 faded off first on November 30, 1995, when it was over four billion miles from its point of origin. The probe was so far away that even at the speed of light, the final signals from Pioneer 11 took over six hours to reach Earth.

Pioneer 10 lasted a while longer than its near-twin, transmitting scientific data until April 27, 2002. The final signal was detected on January 23, 2003 at a distance of over 7.5 billion miles.

Where Will They Go?

Pioneer 10 and 11 were flung off in opposite directions due to their encounters with Jupiter and Saturn, respectively. Though neither probes are headed towards the Alpha Centauri system, they will take roughly 100,000 years to reach that distance of just over four light years. While one might a bit more speed for an interstellar probe, the Pioneers were the first to examine the edge of our Sol system, our celestial doorstep into true interstellar space.

They also paved the way for the more sophisticated probes Voyager 1 and 2 and also played a large role in those craft having their own messages to any recipients, the golden Voyager Interstellar Records, whose full story may be read in the 1978 book Murmurs of Earth by the people who made them possible.

Though neither vessel will get more than a few light years to several stars in the relatively early stages of their journeys through the Milky Way, Pioneer 10 is expected to be in the vicinity of the red giant star Aldebaran in about four million years time. Pioneer 11 may visit the star Lambda Aquila four million years from now. Whether any intelligences are circling any of the stars the Pioneers will pass by is essentially irrelevant, for if an ETI is ever to detect and acquire these artifacts of humanity, they will need not only sophisticated interstellar capabilities but a rather advanced detection network and devices to halt the Pioneers’ velocity without damaging or destroying them.

Whoever or whatever does find these historic vessels is some distant epoch, I think the last two paragraphs in the Epilog chapter of Pioneer Odyssey sum up their missions and their futures as humanity’s interstellar ambassadors quite well:

“As an epilog to the Pioneer mission to Jupiter, the plaque is more than a cold message to an alien life form in the most distant future. It signifies an attribute of mankind that in an era when troubles of war, pollution, clashing ideologies, and serious social and supply problems plague them, men can still think beyond themselves and have the vision to send a message through space and time to intelligence on a star system that perhaps has not yet condensed from a galactic nebula.

“The plaque represents at least one intellectual cave painting, a mark of Man, that might survive not only all the caves of Earth, but also the Solar System itself. It is an interstellar stela that shows mankind possesses a spiritual insight beyond the material problems of the age of human emergence.”

they forgot to place a message on the Star solid third stage

This is one of my favorite pieces of history. Though I imagine the alien interstellar equivalent of a ‘construction worker’ or ‘mine sweeper’ will be the beings to find the pioneer probes. That it would end up as ‘curio’ at some alien art museum or in the private collection of an Alien trillionaire who has it as the entry piece to his organization’s headquarters on a newly terraformed moon? its hard to imagine any of this…. or it just passes too close to an exploding star and become a bunch of differentiated metal slag and dust? Still, it was worth doing.

Great piece, Larry. Emissaries to eternity, is what they are.

Here is how one group imagines the recovery of Pioneer 10 thousands of years from now:

http://www.orionsarm.com/eg-article/47c1b07834a5f

Steve – You are correct, as you have mentioned elsewhere on Centauri Dreams, that the final rocket stages of all the probes which have left our Sol system are also on their own separate paths into the Milky Way galaxy. As far as I know, they carry no messages or any kind of useful information other than themselves.

My hope is that all future deep space missions (including those which do not leave our celestial neighborhood but will remain out there more or less indefinitely) will carry some kind of information package for any potential finders. This should include the rocket stages which do not fall back upon their place of origin.

See here for a step in that direction: http://faces-from-earth.net/

Eniac – Thank you for the compliment. The Pioneer 10 mission was the first planetary probe to grab my attention, in no small part because my young brain was finally ready to truly appreciate such a thing and for the intriguing metallic message to alien beings which Carl Sagan et al had made and attached to the vessel.

I distinctly recall the cartoon panel (it may have been done either by Herblock or someone who mirrored his drawing style) in my local newspaper showing two residents of Jupiter examining the Pioneer plaque (the probe is seen crashed and smoldering in the background) and commenting that the inhabitants of Earth look just like them but that they apparently do not wear any clothes. The joke is that the Jovians look just like the man and woman engraved on the plaque, but are wearing a business suit and dress, respectively. Scientifically inaccurate on numerous levels, but definitely memorable.

This NASA article on the fortieth anniversary of the Pioneer 10 launch includes a color photograph of the space probe with the plaque attached (and facing inward for protection from cosmic dust impacts):

http://www.nasa.gov/topics/history/features/Pioneer_10_40th_Anniversary.html

One can find many representations of the Pioneer plaque but relatively few of the actual physical METI on the probe itself. As I mentioned in my article, I wish they had engraved both sides to increase the odds for the message’s survival and to improve the chances for getting the attention of the vessel’s recipients that this is a deliberate message for them from the species that made the Pioneers.

This archived page from the 25th anniversary celebration of Pioneer 10 by NASA includes numerous videos of the Pioneer 10/11 team members, including a QuickTime video of Carl Sagan discussing the plaque:

http://quest.arc.nasa.gov/sso/cool/pioneer10/mission/index.html

Nick Sagan, third son of Carl, displayed on his blog some recent info and images of his mother, Linda Salzman, who was the artist for the Pioneer Plaque:

http://nicksaganprojects.com/moms-pioneer-voyager-interviews/

I have not yet seen this short animated film, but the brief information says the story involves some ETI finding Pioneer 10 and its plaque and coming to a small town on Earth, armed only with the knowledge it has about humanity from the little golden rectangle:

http://filmfest.dragoncon.org/2009/r-s-2009/rosfeld/

A kind of similar thing happened with the Voyager Interstellar Record in the 1984 science fiction film Starman. No waiting millions of years for aliens to find these message for Hollywood, no sir!

LJK,

we need a astrodynamics study and AIAA publication on the topic, “where will the upper stages be in millions of years”

pioneer 10

pioneer 11

voyager 1

voyager 2

new horizons

commercial operators could allow employees and or the public to submit payload……………..

ljk: “As far as I know, they carry no messages or any kind of useful information other than themselves.”

That isn’t so terrible. Not ideal, but not a total loss.

The trajectory and therefore the origin can be determined with little difficulty even if the probe had a recent gravitational encounter. Radiometric dating of the RPG would give an approximate flight time. Materials and instrumentation analysis would provide lots of info about our resources and technology. There would be lots of lettering embossed on structural and instrument components that would convey some information. Even the lack of an explicit message would indicate that we didn’t expect the probe to be discovered, or care, which would tell them something about us.

It would like us doing anthropology and paleontology.

Here is an interview from 1994 with Dr. Hans Mark explaining how the plaque got onto the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes, along with that cartoon I mentioned above:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogPIvzhHaTE

The series The Beauty of Diagrams focused on the Pioneer Plaque, part 1:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VCaS4mP7aCg

And part 2 here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJhOZyzHQrU

Ron S said on May 1, 2012 at 21:02:

“Even the lack of an explicit message would indicate that we didn’t expect the probe to be discovered, or care, which would tell them something about us.”

Yes, which is essentially what happened with the New Horizons probe launched in 2006 and is on its way to flyby Pluto in 2015. The spacecraft team was neither interested in putting together a Pioneer Plaque or Voyager Record level of information package on their probe, nor did they bother to ask any outside groups to do the job for them.

Instead what was placed aboard New Horizons, while not valueless, was more akin to a small town time capsule rather than something that was aimed at being deliberately comprehensible for any ETI finders.

The one interesting item were the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the man who discovered Pluto in 1930 and had died in 1997. Technically he is the first human being to ever eventually leave the Sol system in some bodily form. Though I wonder how much even an advanced ETI or our spacefaring human descendants could gleam about our species from that sample other than we are made of carbon.

The details are here:

http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html

Long after their missions have faded for the general public, the messages and information placed aboard the Pioneers and Voyagers for ETI are still remembered and able to inspire over almost everything else about those probes. I am not certain that New Horizons will have that same legacy with regards to most of its trinkets.

For those of you who did not like the fact that the female human on the Pioneer Plaque was not waving like the male, artist Jon Lomberg fixed that on the Voyager Interstellar Record, as seen here in this diagram of vertebrate evolution:

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/images/image052.gif

And for those of you who were unhappy about the other missing aspect of the female representative on the plaque, Joe Davis took care of that:

http://www.viewingspace.com/genetics_culture/pages_genetics_culture/gc_w03/davis_j_webarchive/davis_profile_sciam/jd.htm

This has become an amateur obsession with me. Aside for looking at the technical details of the pioneer 10 & 11, its all the ‘interconnected’ stories that make this an unusual piece of cosmic para-memorabilia. Luckily, Joycelyn Bell discovers ‘pulsars’; and expands so quickly that this ‘data’ is put into the plaque. The political decisions between the Johnson Administration through Nixon’s 1st term on ‘post-Apollo’ applications bounced around whether those 2 ‘birds’ were ever going to fly? Pity Dr. Hunter S. Thompson never got around NASA; ‘Firecrackers of the Cosmic HItch-hikers’

I think someday for humans, we’ll ask,’How close could this mission have had just evaporated?’ I hope we do this again…. clever and determined ways to letting other intelligences in the galaxy know, we’re here & we’d like to talk about things that truly last.

http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/2012-08-02/culture/smoca-s-time-capsule-exhibition-is-entertaining-but-lacks-innovation/

SMoCA’s Time-Capsule Exhibition Is Entertaining But Lacks Innovation

By Claire Lawton Thursday, Aug 2 2012

Thankfully, the spaceship created by conceptual collective New Catalogue and installed at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art isn’t going into space anytime soon.

In 1977, NASA approached American astronomer, astrophysicist, author, and popular science communicator Carl Sagan with a mission: Find out what it means to be a human on Earth and we’ll send it into space, so that intelligent life might one day understand. Sagan and a team of artists compiled a time capsule of 116 images, an assortment of natural sounds and musical collections, and messages spoken in 55 languages on gold-plated audio-visual discs that were attached to NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.

Thirty-four years later, New Catalogue (which includes artists Luke Batten, Jonathan Sadler, Mary Vorhees Meehan, and Neil Donnelly along with composer Judd Greenstein) brought its own sounds, images, and a massive “spaceship” installation to SMoCA to revisit Sagan’s mission on a large, interactive scale.

“You are about to enter a spaceship,” reads the exhibition statement by curator Claire Carter.

“There will be many clues in your surroundings — the design language, the constellation of stars, the greetings inscribed on the walls . . . Join them on a journey of exploration — your presence, imagination, even your physical movement, will become part of the artwork.”

Link to the full article at the top.

Venturing to the Outer Solar System: Pioneer 10 and 11 and the Technology of Long Duration Space Exploration

Posted on March 15, 2013 by launiusr

As the first attempt to send robotic probes to any part of the outer solar system, in 1964 NASA scientists first conceived of what became Pioneer 10 and 11, missions that undertook a “windshield tour” of Jupiter and Saturn as they headed out toward the interstellar medium.

Although severe budgetary constraints prevented starting the project until the fall of 1968 and forced a somewhat less ambitious effort, Pioneer 10 was launched on March 3, 1972. It arrived at Jupiter on the night of December 3, 1973, and although many were concerned that the spacecraft might be damaged by intense radiation discovered in Jupiter’s orbital plane, the spacecraft survived, transmitted data about the planet, and continued on its way out of the solar system, away from the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

Full article here:

http://launiusr.wordpress.com/2013/03/15/venturing-to-the-outer-solar-system-pioneer-10-and-11-and-the-technology-of-long-duration-space-exploration/

To quote:

Both Pioneer 10 and 11 were remarkable space probes, stretching from a 30-month design life cycle into a mission of more than 20 years and returning useful data not just about the Jovian planets of the solar system but also about some of the mysteries of the interstellar universe. In spite of this, these missions have been treated in the historical literature mostly as precursors for the much more famous Voyager 1 and 2 missions launched later in the 1970s.

Even so, the these two probes “pioneered”—double entendre intended—much of the technology that made outer solar system exploration possible. This included long-lived space systems, radiation hardened electronics, more robust and capable propulsion systems, more effective data transmission and reception communication technologies, and operational techniques that could be sustained over an indefinite period of time. Most important, they employed radioisotope power systems (RPS) that provided electrical power to the spacecraft for years far beyond the effective range possible for the use of solar energy systems. This allowed a mission duration of years rather than a few months.

While every study of solar system exploration mentions Pioneer 10 and 11, little is known about them, their origins, their evolution, and the results of their missions. Only one book of substance relates solely to this effort, Mark Wolverton’s The Depths of Space: The Pioneers Planetary Probes (Joseph Henry Press, 2004), but there is more to work needed. What is to be Done?