As we continue to think about the implications of Planetary Resources and its plans for asteroid mining, I was interested to see exoplanet hunter Sara Seager (MIT) make a rousing case for the company’s ideas and for commercial space ventures in general. Seager, who works with Planetary Resources as a science advisor, tells The Atlantic‘s Ross Andersen in a May 14 interview that one reason for optimism is the progress we’re making with robotics. Mining operations currently being managed beneath the seas are being handled by robotics. Couple that with our ability to get to and orbit an asteroid as well as to scoop up surface materials and you have all the ingredients for a workable mining operation in a low-gravity environment.

Seager explains that asteroids are attractive mining targets because unlike fully formed planets like the Earth, their heavier elements have not largely sunk inside through planetary differentiation in the early days of the planet’s existence. Asteroids are either fragments of bigger objects or building blocks that were never fully formed, meaning that high-value platinum metals should be readily accessible on the right kind of object. Their low gravity and, in the case of NEA’s, proximity mean that they are attractive targets from which to return materials.

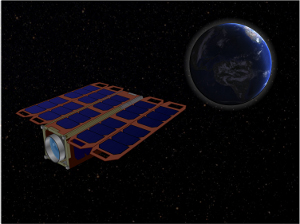

Image: All the technologies may be falling into place for asteroid mining. But is a move to commercial operations a story with even bigger implications? Credit: NASA.

Planetary Resources is intriguing not only because of potential mining returns but because it involves a different model of detail and risk than would be acceptable in a government-created program. Here Seager invokes the Mars Science Laboratory, a $2 billion mission that will land a rover on Mars this summer. MSL became a huge operation because it is a general science mission that demands the 10 different science instruments aboard the craft, making it a heavier rover and demanding a landing system far more complicated than the air-bag methods we’ve used successfully in our last several Mars landings. A private firm, on the other hand, can focus tightly on a specialized goal rather than aiming for a multi-purpose mission from the start.

But there’s a bigger difference, adds Seager:

In the private spaceflight world there are focused goals with profit and new capability as priorities. At NASA the motivation for space missions is different. In addition to big and general science goals, the main goal appears to be not to fail. In this sort of culture the bigger space companies and academia are taught that it, the mission, has to work.

Even the large space companies like Lockheed and Northrop Grumman can become trapped inside this paradigm, for they are not creating long-term, sustainable businesses with the work they perform for the government. Instead, they are operating within a culture riddled with bureaucracy and plagued with high costs. Seager likes the look of young and lean space companies:

…at small space companies, things can fail. Risk is part of developing new technology. Also, for the big space companies the whole competition is just getting the government contract. The competition is not about making something awesomely cool, first to market, and making a ton of money out of it. So in my opinion, the motivation factor and the risk aversion factor make it basically impossible for these larger companies to shift gears. The question that is on the minds of a lot of people is “Can America continue to be competitive in space with the current paradigm?” And the answer is no. That is the reason we have seen the rise of the commercial space flight world—they’re trying to start a new paradigm for spaceflight with a sustainable business that doesn’t just rely on government contracts.

The Seager interview is well worth your time as she discusses not only the Planetary Resources business model but the implications involved in getting a new generation of small and inexpensive technology into space. It’s no surprise that the Arkyd series of spacecraft should catch her eye, since Seager is also involved in a project called ExoplanetSat, a prototype ‘nanosatellite’ that can monitor a single, Sun-like star for two years. This gets seriously interesting when you start talking about producing a large number of such satellites, because while we have the Kepler mission monitoring planetary transits in a fixed field, we have no mission in the works to hunt for planets around the nearest and brightest stars.

So instead of a single space telescope fixated on tens of thousands of stars, most of them distant from the Sun, we invert the model to produce a fleet of tiny telescopes with a single target each, with the detailed properties of each star under observation programmed into each instrument. You can see why Planetary Resources’ plan to launch a large number of small space telescopes would appeal to Seager. The Arkyd series (based on the company’s original name) would allow small institutions to buy a space telescope for a price ranging from $1-10 million, opening space-based observations to universities or even wealthy individuals.

Image: ExoPlanetSat is just 10 centimeters tall, 10 cm wide and 30 cm long, and will complement existing planet-hunters like NASA’s Kepler space telescope and ground-based assets. It gives NASA the ability to dedicate relatively inexpensive assets to stare at a star for long periods of time to look for transits. Credit: MIT/Draper Laboratory.

Here again Seager sees Planetary Resources tweaking the basic model of how science gets done. A telescope specifically designed for a unique science goal can produce superb results, as we’ve learned from Hubble, CoRoT, Kepler and other missions. But bring a commercial interest into the mix and a new flexibility emerges. Planetary Resources can sell small space telescopes into a new market, while also using the product for its asteroid characterization work. The mix of motivations provided by commercial space drives the enterprise. Adds Seager, “If you’re part and parcel of the commercial space flight world, it appears you can get a lot of interesting things done. I think that in academia we could learn a lot from the business world.”

The Most Profitable Asteroid Is…

by Nancy Atkinson on May 16, 2012

With the recent announcement of the asteroid mining company, Planetary Resources, some of the most-asked questions about this enticing but complex endeavor include, what asteroids do we mine? Which are the easiest asteroids to get to? Could it really be profitable?

While Planetary Resources officials said they hope to identify a few promising targets within a decade, the initial answers to those questions are available now on a new website that estimates the costs and rewards of mining rocks in space.

Called Asterank, the website uses available data from multiple scientific sources on asteroid mass and composition to try and compute which asteroids would be the best targets for mining operations.

So, which asteroids are most profitable, valuable, easily accessible and cost effective?

The winners are, according to Asterank…

http://www.universetoday.com/95169/the-most-profitable-asteroid-is/

http://www.universetoday.com/95180/space-exploration-by-robot-swarm/

Space Exploration By Robot Swarm

by Jason Major on May 15, 2012

With all there’s yet to learn about our solar system from the many smaller worlds that reside within it — asteroids, protoplanets and small moons — one researcher from Stanford University is suggesting we unleash a swarm of rover/spacecraft hybrids that can explore en masse.

Marco Pavone, an assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University and research affiliate at JPL, has been developing a concept under NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Program that would see small spherical robots deployed to small worlds, such as Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos, where they would take advantage of low gravity to explore — literally — in leaps and bounds.

Due to the proposed low costs of such a mission, multiple spacecraft could be scattered across a world, increasing the area that could be covered as well as allowing for varied surfaces to be explored. Also, were one spacecraft to fail the entire mission wouldn’t be compromised.

The concept is similar to what NASA has done in the past with the Mars rovers, except multiplied in the number of spacecraft (and reduced in cost.)

The robots would be deployed from a “mother” spacecraft and spring into action upon landing, tumbling, hopping and vaulting their way across low-mass worlds.

In addition to providing our first views from the surfaces of such worlds, Pavone’s hybrid rovers could also help prepare for future, more in-depth exploration.

“The systematic exploration of small bodies would help unravel the origin of the solar system and its early evolution, as well as assess their astrobiological relevance,” Pavone explains. “In addition, we can evaluate the resource potential of small bodies in view of future human missions beyond Earth.”

Read more from NASA’s Office of the Chief Technologist here:

http://www.nasa.gov/offices/oct/home/feature_cosmos.html#.T7KGYvxmxwo.facebook

In 2003, I came up with the idea of small space probes resembling soccer balls that could be bounced around the rings of Saturn, taking measurements and images of the particles and boulders in that system.

The details are here:

http://www.mail-archive.com/europa@klx.com/msg03001.html

At the very least, the idea of images from deep within the Saturn ring system with the gas giant planet in the background has tremendous visual appeal.

The total supply of platinum is worth just a few billion dollars. Even if it was just lying around in chunks on an asteroid, how feasible would it be to make money on this resource? Given the high risks, assuming a 10:1 return, would require the mission to cost less than a few $100 million to replace the total global production of this metal.

One could imagine the most profitable strategy simply would be to greenmail the South African suppliers with a threatened oversupply.

Funding and completing SIM would be a more comprehensive way to examine all nearby stars for planets. Perhaps it would cost more then a small fleet of mini-sats but SIM will detect exoplanets regardless of their orbital alignment to our line of sight. Looking for transits is fine for Keplers’ statistical census but if you want a complete survey of all nearby stars then I think SIM would be the better choice then mini-sat transit observers.

Excellent article, Paul, and exciting times, especially as these new capabilities are progressively married to lower-cost access to orbit. It needs stressing that these are the basic technologies for any kind of space industrialisation (including solar power satellites), manned planetary exploration, space colonisation, and of course interstellar exploration.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Alex Tolley:

About $10 billion per year. If you could supply one tenth of it, you’d have a tidy annual revenue of $1 billion, not all that bad. And presumably there is other metals to diversify into.

Now, the question of course is if you could do it at a positive margin, and it has no obvious answer.

Here is an online paper titled “The Role of Near-Earth Asteroids in Long-Time Platinum Supply” from 2000:

http://www.nss.org/settlement/asteroids/RoleOfNearEarthAsteroidsInLongTermPlatinumSupply.pdf

Mike-while SIM would be more useful, it would also cost so much that there would be a danger of the project being cancelled. Small telescope such as this, can be funded by a university of foundation and its failure would not ruin years and years of work.

Also I wonder-could we use such small telescope to observe Alpha Centauri?

It won’t happen for one simple reason. Government(s).

To Wojciech, unfortunatly SIM was cancelled. The Space Interferometry Mission would have employed the astrometry method to discover exoplanets. It would have detected planets regardless of orientation of their orbital plane to our line of sight providing the target star wasn’t too distant.

I think within about 30 light years or so. This instrument would have been ideal for a nearby survey. The transit method can only be expected to detect exoplanets in orbits edge on to our line of sight. Maybe only 2 percent of targeted stars, perhaps only .5 to 1 percent for Earth size worlds in habitable zone orbits. This is fine for the Kepler mission looking at 150,000 stars because then we can extrapolate the detections to get a very good statistical summary of the types and numbers of planets hosted by main sequence dwarfs.

But if you use the transit method for any specific star it will be a very poor gamble regardless how relatively cheap the approach because of the 99 percent uncertainty of the results. Why bother at all?

As for Alpha Centauri, the Alpha Centauri A and B binary orbit is angled a little to our view. It is likely that any planets that orbit either of these stars would be in the same orbital plane thereby there would be no transits appearing from our line of sight. Anyway even if A or B had transiting planets the ongoing 3 radial velocity planet searches would detect them as well.

The transit method for exoplanet hunting is a very powerful and useful approach for a large number census which is what the very successful Kepler

mission is all about.

But to use it to look at any specific star is useless because all you will likely get is a 99 percent null result that will indicate nothing about the presence of planets at any specific star. A waste of money.

I know that SIM mission was cancelled. The current proposal is probably the reaction to this. Its better to have more decentralised program, that can take blows more easily, and has higher chance of succeeding.

Building a telescope to observe only a single star strikes me as supremely inelegant and wasteful, no matter how small and cheap the telescope. Especially if being small and cheap limits its power, which stands to reason. It is unlikely that the reduced price can make up for the combination of reduced power and reduced target range.

The multi-telescope concept only makes sense when the combination of many telescopes increases observational power, as in an interferometric array. Of course, then you end up with a large asset for which targets have to be selected by the usual peer-review process. No staring at single stars, at least not for long…

As Mike said several times above, it doesn’t matter how big or small or many or few are the telescopes aimed at one particular star, if they are looking for transits they are nearly all useless, because the chances of planets orbiting exactly between their star and Earth are next to zero. You need an interferometry telescope, like SIM.

Yeah, SIM seems like an extraordinarily good idea, especially if you are only interested in stars that are close by.

I suspect that this is what killed it: It would provide planet information on too few stars, and the goal of reaching them one day is too remote to have been considered by the decision makers. It is likely that Kepler will find orders of magnitudes more planets than SIM could, despite the well known handicaps of transit. Also, transit gives you diameter and density information, which SIM would not have, I think.

That said, I think that a new and improved high precision astrometric mission will happen, hopefully sooner rather than later.

Asteroid activists launch fund-raising campaign for space telescope

By Alan Boyle

Leaders of the nonprofit B612 Foundation today took the wraps off a campaign to fund and launch a space telescope to hunt for potential killer asteroids — a campaign they portrayed as a cosmic civic improvement project.

Former NASA astronaut Ed Lu, the foundation’s chairman and CEO, estimated that hundreds of millions of dollars would have to be raised to fund the project, but said he was “confident we can do this.”

“We’ve been at this particular project for a year now,” Lu told me in advance of today’s campaign kickoff at the California Academy of Sciences’ Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco. “We have people who are internationally well-connected, and we have a message that we think resonates with people ranging from large donors to perhaps half a million kids worldwide.”

The foundation’s aim is to identify and map the orbits of half a million asteroids that are on trajectories approaching Earth over the course of five and a half years, using a spacecraft that’s launched into a Venus-type orbit on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in the 2017-2018 time frame.

Apollo astronaut Rusty Schweickart, B612’s chairman emeritus, said the task could be key to humanity’s long-term survival. “We feel a certain urgency to get on with it so that we can be confident that we’re not going to have a cosmic disaster here for no good, justifiable reason, just because we didn’t get with it,” he said in a statement. “So let’s get with it. That’s the name of the game.”

Full article here:

http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/06/28/12450778-asteroid-activists-launch-fund-raising-campaign-for-space-telescope

To quote:

What’s the risk?

The potential risk posed by near-Earth asteroids was highlighted earlier this month when a kilometer-wide (0.6-mile-wide) asteroid called 2012 LZ1 sailed within 3.3 million miles (5.3 kilometers) of our planet, just a few days after its discovery. If a rock that big were to hit Earth, it could end civilization as we know it. Smaller asteroids, around 40 meters (130 feet) in diameter, could set off atom-bomb-scale explosions like the 1908 Tunguska impact, which flattened 500,000 acres (2,000 square kilometers) of forest in Siberia.

Expensive, difficult, and dangerous

Many people dismiss space ventures because of the cost and risk associated with them. However, as Greg Anderson notes, in the 19th century many felt the same way about traveling to California, yet the promises of riches from gold discoveries there was compelling enough for some to accept the risks and reshape history.

Monday, October 22, 2012

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2175/1

To quote:

When the outside world learned of the discovery of gold in California, humanity as a whole did not note the discovery, coolly assess the rigors involved in getting it, and decide, even though that added wealth would be extremely useful, not to pursue it. Instead, some individuals accepted all the risks, set out for California for a myriad of personal reasons, and ended up setting the world on a different course. California gold was instrumental in funding the Union effort through the American Civil War. The huge new state was a magnet for westward migration of Americans, and immigrants, seeking a new start and a better life. Today, California is one of the easier places to reach. Airlines from around the world fly there. Huge ports host ships from around the world. The interstate highway system ties California firmly to the rest of the nation. On its own California would be a major global economic power.