We all carry our assumptions with us no matter where we go, dubious extra baggage that can confuse not just our scientific views but our lives in general. That’s why it’s so refreshing when those assumptions are challenged in an insightful way. Think, for example, of the starship as envisioned by Hollywood. In our times it looks like something produced by the joint efforts of NASA, ESA and other governmental space agencies. No matter how diverse the crew, the model is always based on western culture, the assumptions reflecting our modern ethos.

When an assumption is ripe for questioning, along comes a writer like Michael Bishop. Consider the starship Kalachakra, carrying a crew of 990 to a planet in the Gliese 581 system, as envisioned in Bishop’s ‘Twenty Lights to the Land of Snow,’ a novella in the Johnson/McDevitt book Going Interstellar. Most of the crew spends the flight in hibernation using the wonderfully named drug ursidormizine — thus slumbering ‘bear-like’ — but each crewmember must emerge every couple of years to avoid the deterioration the process creates in the sleeping ‘somnacicles.’

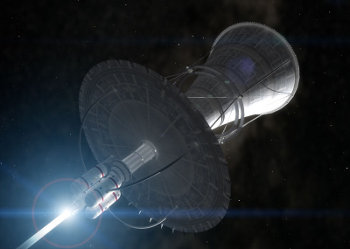

Image: The culture aboard a starship may be nothing like what Hollywood so often envisions. Speculations along these lines are fine fodder for science fiction, and remind us that an interstellar future is multi-disciplinary, demanding our best efforts not just in science but in philosophy, sociology and culture. Credit: Adrian Mann.

Kalachakra carries Free Tibetans escaping a tyrannical government, the most prominent among its crew being the Dalai Lama, who inconveniently dies early on and must be replaced. I won’t get into plot details because in my estimation, the cover price of Going Interstellar would have been justified even if the Bishop story were the only thing in the book. You’ll want to read this for yourself, and anticipate along with me the novel that will surely come out of it. You’ll especially enjoy the defeat of expectations at every turn. Here, for example, is a look into the hangar where the Kalachakra carries the lander that will be used on arrival:

An AG [anti-gravity]-generator never runs in the hangar because people don’t often visit it, and our lander nests in a vast hammock of polyester cables. So we levitated in a cordoned space near the nose of the lander, which the Free Federation of Tibetan Voyagers has named Chenrezig, after that Buddhist disciple who, in monkey form, sired the first human Tibetans. (Each new DL [Dalai Lama] automatically qualifies as the latest incarnation of Chenrezig). Our lander’s nose is painted with bright geometric patterns and the cartoon head of a wise-looking donkey wearing glasses and a beaked yellow hat. Despite this amusing iconography, however, almost everyone on our strut-ship now calls the lander the Yak Butter Express.

That last bit, the donkey in the yellow hat, is just right — no somber United Federation of Planets logo or some such aboard the Kalachakra! In the story, the journey at one-fifth of light speed is funded by a United Nations charter and all sorts of diplomatic maneuvering designed to solve a political crisis by creating a new ‘land of snow’ in the high mountains of Gl 581g’s terminator. Never mind that Gl 581g most likely doesn’t exist, for it was thought to be there when Bishop wrote the story, and it shows up elsewhere in Going Interstellar as well, a reminder of how fast our exoplanet knowledge is changing. The point is, this journey is all about coming of age, learning who you are, and creating meaning out of uncertainty. It’s just a great read.

Perils of the Book Reviewer

Now and again I’m asked about the ‘What I am Reading’ window on the Centauri Dreams main page, and why it takes me so long to get through a book. I’m not actually as slow a reader as it appears. Going Interstellar was up there for several weeks because I never read a single book at a time, but usually have several going simultaneously. I always try to put the book of most interest to my readers up in the window, but I only have room for one. The pace — and the blog format — have changed the way I review books in general. Rather than writing a single, monolithic review as I used to do for newspapers, I’m more prone to write about a book while it’s in progress, coming around to it again and again before moving on to the next volume.

Thus it has been with Going Interstellar, about which a few more thoughts. You’ll recall that this is a collection of essays and fiction, mixing them in the fashion of Arthur Clarke’s 1990 book Project Solar Sail. I had mentioned the similarity before but was startled to find Mike Resnick’s story ‘Siren Song’ at the end of the book. Like the Clarke volume, which includes Clarke’s ‘The Wind from the Sun,’ the Johnson/McDevitt book includes a story about a solar sail race, or I should say in this case a race in which a single solar sail appears. Resnick’s is a moody little evocation of Odysseus that’s less interested in showing solar sailing at work than in mining the mythic ore that our move into the Solar System will invoke.

The fiction in this book is spry and interesting. Along with the Bishop and Resnick, I thought particularly highly of Les Johnson’s ‘Choices’ and Sarah Hoyt’s ‘The Big Ship and the Wise Old Owl,’ which plays entertainingly off the clues afforded by nursery rhymes on a starship journey to reveal the dangerous machinations that may complicate an interstellar arrival. Jack McDevitt’s ‘Lucy’ takes us into the mind of an AI pushed into what can only be called an ‘awakening’ at system’s edge, one that questions our human limitations and makes us wonder just who is likely to make that first interstellar crossing, machine or human? Ben Bova’s ‘A Country for Old Men’ taps into the same theme, with the notion that there are tricks up the sleeve of our species that even the wisest AI may not be able to fathom.

Fictional Threads in Science

What I appreciate about the mixed format of a book like this is that it keeps you grounded in the possible. The ideas used to get big ships moving into the interstellar deep in these stories are all based on extensions of our current engineering and ideas in line with contemporary physics. We have chapters on antimatter and fusion (Greg Matloff), solar and beamed energy sails (Les Johnson) and Richard Obousy’s introduction to Project Icarus, the ongoing redesign of the British Interplanetary Society’s Project Daedalus starship. I like what Obousy has to say about the project’s objectives, especially in training a new generation of designers:

To maintain the healthy vision of a future where interstellar travel is possible, a new generation of capable enthusiasts is required. Project Icarus was designed with this specific motive in mind, and a quick glance at the Icarus designers reveals an average age close to thirty. Thus, one hope is that upon completion of the project, an adept team of competent interstellar engineers will have been created, and that this team will continue to kindle the dream of interstellar flight for a few more decades until, presumably, they too become grey and find their own enthusiastic replacements.

Starship design brings challenges galore, the chief of these perhaps being the issue of deceleration. As a consultant for Project Icarus, I was privileged to throw my two cents in on the debate over whether Icarus should, like Daedalus, be a flyby mission, or whether incorporating deceleration at the target should be attempted. I was agog at the notion of deceleration given what this would do to the mass ratio, but the more I thought about it, the more I came around to the idea that the team was right. A flyby gives you precious little data for the decades you’ve spent reaching the target, and sooner or later we’re going to have to face the deceleration problem, so better to get working on it now. A solution to this problem alone would be an unforgettable contribution to interstellar studies, if Project Icarus can provide one.

There’s much more of interest in Obousy’s essay, including the fact that the inertial confinement fusion strategy favored by the Daedalus designers — firing deuterium and helium-3 pellets into a reaction chamber at a rate of 250 pellets per second, where they are ignited by electron beams — calls for an improvement of 21 million times over the ignition rate expected from the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory. To say there is much work to be done is to state the obvious, a fact cheerfully acknowledged by this band of visionary designers.

In any case, I’ve rambled on about Going Interstellar without getting into the meat of several of its essays, but I’ll be drawing on these in coming days as we look at further propulsion possibilities. We’re also going to be looking at how rocketry studies were influenced by science fiction in the era between the two World Wars as I draw on John Cheng’s Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012). The new book up in the ‘What I Am Reading’ window is Kelvin Long’s Deep Space Propulsion (Wiley, 2011).

Have I mentioned that I need new reading glasses? I’ll have to get them soon because interstellar ideas are popping up all over the place. I also have Centauri Dreams reader Jim Essig’s new title Call of the Cosmic Wild (2012) ahead. And although it’s not on an interstellar theme, I’m soon going to be talking about Mark Anderson’s The Day the World Discovered the Sun (Da Capo, 2012), received too late to read before the transit of Venus, but telling a tale of transit study in the 18th Century that reminds us what minds fired by curiosity can do with the tools of their time. We’re not in so different a position than those 18th Century astronomers who set sail around the globe to view the 1769 transit. Like them, we work with tools that following ages will find primitive, and in starship terms, our goals are far beyond our grasp. It is the hope of closing that gap even a little that impels the interstellar community to keep trying.

Paul, you really need to stop telling us about all these great new books unless you want everyone who reads Centauri Dreams to potentially go broke! :^) Actually, I find it more than a little interesting and comforting that in these rotten economic times there are still people with optimism about humanity’s future and book publishers willing to support such works. Hey, many rocket societies around the world formed in the 1930s during the Great Depression, so why not?

Regarding that story about Tibetans escaping a tyrannical government (gee, I wonder who that could be?) by staring life on a new world in another solar system. This certainly falls into line with my view that if humans do conduct interstellar travel in person, the first groups will be similar to those who came to the New World from Europe: The political and religious refugees, the treasure seekers, and the antisocial elements. Sure, you might get some scientists tagging along, but as we have seen in our current and historical space programs, science is often just the cover for the real reasons for the big space projects.

Maybe this will change some day, but that will involve the human species making some radical changes as well. This should also make one think about what kind of beings from other worlds could be roaming about the galaxy in their starships, assuming they are not too alien from us. Keep in mind that those who came to America seeking religious freedom in the 1600s often did not extend their desire for freedom to others, both native and fellow immigrants. As for the treasure seekers and the criminals, they didn’t even bother with such pretenses. Everything and everyone was a resource for their immediate benefit.

Having Tibetan refugees start life far from Earth also reminds me of what happened when Gerard K. O’Neill, the guy who came up with the free-floating Space Colonies concept in the early 1970s, suggested that his giant off-world space habitats would make great new homes for the Native Americans that had been displaced throughout North and South America just a few generations earlier by European settlers.

The collective Native American response was “Oh great – first they kick us off our land, now they want to kick us off our planet!” I bet given a choice, the native Tibetans would not want to give up their homeland, either.

What I can see happening is that the rich will start leaving Earth for space to set up residence and business. The question is, will the far less rich be able to follow? An old assumption is yes, because the rich will need lots of employees to help run things. But will advancing technology make it easier, safer, and cheaper to use machines instead of people? A machine mining on a hostile world (and let’s be honest, every other place in the Sol system is quite hostile to terrestrial life) will not require tons of food and living space, nor will it have a family to support or demand higher pay. We see all the time what happens when a corporation has the chance to go the least expensive way possible – why would it be any different in space? And remember, the first space colonists will be corporate, not a collection of noble scientist astronauts. Whether anyone else gets to follow in a serious manner (and by serious I mean more than tourists) will be up to them.

Paul in regards to decelerating at the target system, you didn’t say by how much deceleration would be needed to get useful information, I’m curious to see what requirements it would take to at least slow the probe down from an encounter that takes minutes to possibly h0urs or days.

I watched Prometheus land on the alien planet and was thoroughly entertained!

The ship landing in 3D was my Sci-Fi dream come true! The ship was cool incorporated.

Yes, one had to suspend lots of disbelief and not worry about how it only took a couple of years for the ship to get many light years across space. But hey, who’s counting, right?

And there is no mention of how Prometheus slows right down upon entering the system…oh well, “standard orbit Mr. Sulu”!

Space probably belongs to robotic systems and AIs, unless we make concerted effort to make sure that these things remain our tools and not our eventual heirs. They are simply superior for the task, with the exception of brain power and intelligence — for the time being.

Like Bowman, we will need to contain or even shut down HAL if we are in danger of being usurped.

Greg, the deceleration needs to match the initial acceleration (plus or minus a relatively tiny bit depending on the relative motion of the star to the Sun). If it is a colonisation ship, then it needs to go into orbit in the target system. If it is a scientific probe, then it needs to place spectroscopes and microscopes on the surfaces of rocky planets in the system.

The benefit of slowing down is small until you come to a full stop. If you have 1 minute at 0.2c, that makes 2 minutes at 0.1c, or 20 minutes at 0.01c. Adding the (almost negligible in terms of energy) extra 0.01c of delta-V for a full stop gets you decades instead of 20 minutes.

Also, consider, at a given mass-ratio all it takes to decelerate is double the travel time. Given a delta-V capability of 0.2c, you can choose to do a fly-by of Alpha Centauri in 20 years, or a full stop in 40 years. In the first case, you get a few minutes of data, in the second, decades.

It seems like a slam-dunk to me, and I am not sure I even understand why flyby was proposed initially and why it is still being talked about.

I do not want to turn this into a Prometheus discussion, because quite frankly it was a science fiction film that was very poor when it came to the science in it (this includes the starship), along with the motives of most of the characters, including the ETI.

I can only think that people who are raving about Prometheus either do not care if it is scientifically accurate or not or if they were dazzled by the special effects, which considering how most mainstream SF and fantasy films these days have huge budgets and armies of CGI and technofolks to make those glorious special effects, they should not be quite the stunner they used to be back when cinematic special effects still required physical models.

For those who do care whether or not science fiction films at least try to be accurate once in a while, read here why Prometheus fails on multiple levels:

http://spacearchaeology.org/?p=371

and here:

http://digitaldigging.net/prometheus-an-archaeological-perspective/

If you want a recent SF film with a plausible starship, check out the ISV Venture Star from Avatar. Now that I think about, how many plausible interstellar vessels have there been in cinematic and television history? And by plausible I do not include FTL.

Eniac, regarding the flyby plans for Icarus, originally the Daedalus probe was going to be only a flyby mission, as the BIS team considered trying to stop in the target star system to be too much in terms of fuel, cost, etc.

While I agree that stopping in the star system would be best and good practice for future interstellar missions, if they could not stop their probe in the system, would leaving transmitting instruments work? By the time we can send a probe to another star, shouldn’t the technology be sophisticated enough to allow those back in the Sol system to pick up the signals of smaller probes left in the alien system?

And has anyone considered the possibility of Icarus visiting more than one star system if it did remain a flyby probe? And what if by the time we really can build a star vessel, would building two or more be plausible?

Eniac, your using acceleration being equivalent to deceleration in time and energy, the delta-V is equivalent on both sides of the curve. I was curious if energy for acceleration was spent on a ‘boost’ phase then a mechanism, possibly a magnetic or gravitational ‘brake’, was used to decelerate sharply at the target system, not to a full stop but long enough to ‘loiter’ in system to collect more information than a direct fly-by.

Larry Krauss wrote a book….The Physics of Star Trek….trashing all the physics of Star Trek….Rebuttal anyone?…..

JDS

It might be possible to–up to a point–“have one’s cake and eat it, too” with regard to conducting either a stellar system flyby mission (with no deceleration from cruise velocity) or a stellar system rendezvous (“decelerate and ‘stop'”) mission. A rendezvous starship (or starprobe) could release flyby probes at maximum velocity, before the main vehicle begins to decelerate.

This would provide “teaser” data and images from the target stellar system well in advance of the main vehicle’s arrival. Besides providing a quick “sneak peek” of the destination for the impatient flight controllers and project scientists, this would also be useful for refining details of the main vehicle’s arrival and its interplanetary travels (including planetary gravity assist maneuvers) and/or planetary probe dispatches once it achieves orbit around the target star.

In a Daedalus-style flyby mission design, most of the data is initially gathered not by the starship itself, but by small sub-probes making close, brief (~seconds) flybys of the individual planets in the target system. To get more data out of this approach, the easiest way is not to decelerate anything, but to have multiple sub-probes flying by the same planet at times spaced hours or days apart. (This also lets you see the whole surface of an Earth-like planet, not just the side that is illuminated as the sub-probe flashes past.)

A rendezvous mission with full deceleration calls for a completely different approach. There are no sub-probes, and only one copy (or at most a few copies) of each instrument. After arrival, the starship spends decades visiting each planet in turn, doing a full study from low orbit, before moving on to the next.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/10/opinion/sunday/what-physics-learns-from-philosophy.html

Speaking of Krause. He really likes to trash…He didnt like the review of his book in the NYT . David Albert really trashed it . Apparently Krause hasnt figured out the google yet. Albert did work with Aharnov of Ahnrnov -Bohm

He is an accomplised phyicist as well as a philopher.

OK, being that I’m not an astronomer, engineer, or scientist, this will probably be categorized as a “strawman” question. Take the illustration of the interstellar probe above: could you slow down at the target star system by having the Probe/starship do a 180 degree turn and fire the engines toward said star? Just curious. Thanks.

James D. Stilwell said on June 20, 2012 at 19:51:

“Larry Krauss wrote a book….The Physics of Star Trek….trashing all the physics of Star Trek….Rebuttal anyone?…..”

What is there to rebutt? If someone here or elsewhere knows how to build a starship that can exceed the lightspeed barrier, great, but otherwise I would say Dr. Krauss knows what he is talking about. The reality of physics won’t stop Hollywood in any event.

David said on June 20, 2012 at 22:47:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/10/opinion/sunday/what-physics-learns-from-philosophy.html

“Speaking of Krause. He really likes to trash…He didnt like the review of his book in the NYT . David Albert really trashed it . Apparently Krause hasnt figured out the google yet. Albert did work with Aharnov of Ahnrnov -Bohm

He is an accomplised phyicist as well as a philopher.”

Krauss may be cranky, but does that make his physics wrong? I have always found Sir Isaac Newton to be an obnoxious nerd, but that doesn’t reduce his contributions to science. And Galileo was Mr. Ego, but he did some good for astronomy as well.

@Tony D.: Sure, you just need to reserve enough fuel to do so… assuming the type of ship pictured above.

Depending on the rate of fuel use, perhaps you can thrust 1/2 the way there, turn around, and thrust to decelerate the entire rest of the way. Then you can have “artificial gravity”, at least at the level of your acceleration/deceleration. However, for the engines plausible today, the thrust would either be very low (not much artificial gravity), or only applied at the beginning and end of the journey, with a long, zero-g cruise in-between. A rotating section to produce centrifugal force would be useful in either case.

But the real trick is having enough fuel to both get up to a reasonable speed, then later to slow back down, since the changes in kinetic energy are tremendously large for siginificant fractions of the speed of light.

While ljk yesterday didn’t wish to make this discussion about Prometheus, I would like to discuss it at least somewhat. I just saw the movie quite recently and it was interesting but I’m not quite sure what to make of all of it. If I recall correctly they had undertaken a voyage of about 240 trillion miles or what seem to be approximately 40 light years in about, oh what I would say would have been about three years. Aside from all that, I did find myself with at least a few questions that I thought perhaps others might be able to answer for me.

Fassbender (David) was undoubtedly the most penetrating character out of all those that were portrayed. The most pressing questions I had were why did David seek to go ahead and infect both the male and female lead scientist with alien creatures? Why would David wish to have these animals brought back to earth seemingly to contaminate us? And secondly why did the Engineers wish to create us and then seemingly wish to come to earth with their WMDs so that we would be completely annihilated?

Finally why would a multitrillionare wish to finance a mission supposedly in which the only intention would be to find out where we came from? That seems kind of a stupid waste of money. Any answers anyone?

bill said on June 21, 2012 at 14:09:

“While ljk yesterday didn’t wish to make this discussion about Prometheus, I would like to discuss it at least somewhat. I just saw the movie quite recently and it was interesting but I’m not quite sure what to make of all of it.”

LJK replies:

Besides the fact that Prometheus is not really relevant to this topic and vice versa, the other reason I did not want to discuss that film is because it is just awful science on multiple fronts.

But, to answer your questions….

Bill says:

“If I recall correctly they had undertaken a voyage of about 240 trillion miles or what seem to be approximately 40 light years in about, oh what I would say would have been about three years.”

LJK replies:

That is because the Prometheus starship runs on Fantasy Drive, like most Hollywood SF star vessels (a character also mentioned that the ship had gone half a billion miles to get to that target star system – oy). And we will have manned star travel by 2089, apparently. Well, only if a really rich guy funds the whole thing. Okay, that at least has some plausibility.

As I said elsewhere in this comment thread, the ISV Venture Star from Avatar is at least based on a plausible design, which you can learn more about here:

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/realdesigns.php

And here for good measure:

http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Interstellar_Vehicle_Venture_Star

Bill then asks:

“Fassbender (David) was undoubtedly the most penetrating character out of all those that were portrayed. The most pressing questions I had were why did David seek to go ahead and infect both the male and female lead scientist with alien creatures? Why would David wish to have these animals brought back to earth seemingly to contaminate us? And secondly why did the Engineers wish to create us and then seemingly wish to come to earth with their WMDs so that we would be completely annihilated?”

LJK replies:

Because Ridley Scott wants you to find the answers to your questions by handing over your hard-earned money to see the sequel to this film, that’s why! Plus you cannot have a member of the Alien film franchise, even a pseudo-prequel, without someone having some horrid little alien creature burst out of them somewhere.

With even more seriousness, you will find your answers in Persian creation mythology. And Scott is apparently a big believer in the ancient astronauts concept. He also seems to have lost whatever skills he had at making decent science fiction films between Alien and Blade Runner and now.

Bill then inquires:

“Finally why would a multitrillionare wish to finance a mission supposedly in which the only intention would be to find out where we came from? That seems kind of a stupid waste of money. Any answers anyone?”

LJK replies one more time:

Because like most superich megalomaniac CEOs, he wanted to live forever and he believed the aliens held the key to his quest. You don’t really think he did this for the advancement of scientific knowledge, do you?

Another clue that science was not the primary goal of this expedition was the selection of the team, which made it clear they apparently got their education and field experience from watching other bad SF films that send starships to alien planets.

Supposedly there were some real science advisors on the set of Prometheus, but it is rather clear any advice they may have been able to give was ignored. I also read an interview with Ridley Scott who commented that when Carl Sagan told him the biology and other science in the first Alien film was messed up, Scott replied that it was just a movie and that Sagan should “lighten up.” You could just feel Scott also intoning to Sagan that he wanted the science nerd to shut up because he was a big Hollywood director and he could do anything he wanted with his film.

If someone can figure out how to make a starship go 37 light years in just two Earth years and also find aliens who are the reason we are here in the first place (but hopefully they won’t try to exterminate us in the process), then hooray! Otherwise I have said my piece on Prometheus.

Oh yeah, one more: Prometheus was the Greek deity who gave fire to poor little humanity. He was punished by Zeus for this transgression by being chained to a rock and having his liver torn out by a vulture every day. The liver would grow back overnight and the cycle would repeat itself.

So is Director Scott trying to say with his latest creation that humans should not try to learn more about themselves and the rest of the Universe because the deities will punish us for trying to be smarter and improving our lot in life? Shades of don’t bite the apple from that tree!

In his relation to SF , Ridley Scott is a Parasite . Others have created a beliefsystem of an optimistic and forwardlooking nature , and then HE comes along , trying to exploit the value of its myths by DESTROING their inherent selfconfident right to settle the universe . He gobbles it all up and spit out the bones .