By Larry Klaes

Larry Klaes, a frequent Centauri Dreams contributor and commenter, here looks at a new book that explores humanity’s place in the cosmos. Is there a way to rise above our differences of outlook and perspective to embrace a common view of the universe? The stakes are high, for technology’s swift pace puts the tools of exploration as well as destruction in our hands. C.P. Snow explored the gulf between science and literature 50 years ago, but as Larry notes, the division may be broader still as we confront the possibility of intelligent life other than ourselves.

Just about anyone who has even taken the time to go outside on a clear night and stare up at the starry firmament over their head (assuming it is also largely free of the relatively recent artificial impediment called light pollution) has often been moved in rather profound ways by the sight, whether they are astronomically inclined or not. This feeling can be summed up, I think, by this quote from the artist Vincent van Gogh: “When I have a terrible need of – shall I say the word – religion. Then I go out and paint the stars.”

The Universe – or, I should say, what we can see with unaided vision, which amounts to several thousand stars (including the Sun), the Moon, and a few neighboring planets as viewed from Earth – seems to have always evoked such “spiritual” thoughts and feelings since the time of our very distant ancestors: There is the plausible theory that some of the animal drawings found in many of the caves of prehistoric Europe actually represent star patterns. The heavens were where the most powerful gods resided, both visible and hidden. The skies were also home to what various cultures considered their best members, once they passed on from this life (usually their rulers and warriors).

Then science came along and did its level best to end all this superstitious nonsense.

Oh, it all started out innocently enough. Some ancient Greek thinkers like Thales of Miletus simply removed the supernatural elements from the natural explanations for the nature of the world. Others like Democritus considered all gods to be the products of limited and flawed human imaginations and that only “atoms and the void” made up the real Universe. One man named Aristarchus of Samos went as far to say that Earth was a mere planet circling the Sun, which was just one of those numerous points of light in the night sky.

However, the ideas of these guys never quite caught on with most of humanity, which needed to know in their hearts that not only were they more than just a temporary collection of elements, but that someone or something out there considered them to be very special despite their often very obvious limitations and flaws. Thus for most of the next few thousand years, the West stuck largely with religion for their comforting answers, which did not have and often even rejected any solid evidence for the proof of its legitimacy.

Things started to really get torn apart culturally when the Renaissance and the Enlightenment came along. The turning point for this change is often cited as the day that the Roman Catholic Church told the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei to stop supporting the ideas of one Nicholas Copernicus (who was influenced by the aforementioned Aristarchus) and anything else that seemed to contradict what was written in the Bible – or else.

Although Galileo essentially complied with the Church authorities, the ball named science began to really get rolling after this event and gained speed in the following centuries. Among those who did the most to solidify science as the main way to view the Cosmos in those early days of the so-called modern era was Sir Isaac Newton, who showed that it was gravity which kept Earth orbiting the Sun rather than fly off into the void and not bands of angels pushing our planet around our star via God’s Will.

Ironically, Newton was also a devout Christian who intensely studied the Bible to determine, among other things, that the world would come to an end in the year 2060. This was not terribly strange, however, as most scholars of his time and place did not see a division between science and religion; they assumed that God had made the Universe and science was the divinely inspired way for humanity to learn how He did it.

Eventually, though, as science and technology gained a stronger footing in civilization, the division between empirical and spiritual knowledge grew to the point that even today, the general public tends to feel torn and alienated by the perceived coldness and fact-only basis of science and the emotion-based ideas of religion and spirituality. Many folks often end up choosing one viewpoint or the other, conflicting with the other side and their own thoughts and feelings in the process. The results are a current society that is a living paradox, one that has a firmer grasp on how the Universe began than before along with the tools required to make this possible, while at the same time remaining focused on our home world, our baser immediate needs, and holding onto beliefs which our ancient forbearers would still recognize.

Can the two sides be reconciled before our society is presumably wrecked by the cultural clash, and if so, how?

In 2011, Yale University Press released a book titled The New Universe and the Human Future: How a Shared Cosmology Could Transform the World. The authors of this work are Nancy Ellen Abrams and Joel R. Primack, both professors at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who also happen to be a married couple.

As the subtitle of their work states, Abrams and Primack think that a “shared cosmology” could break this conflict our species is currently in: If we would all just agree on the origin and composition of the Cosmos as stated by modern science, and especially our place in it all, we will not only save ourselves but become truly universal beings with unlimited horizons and a renewed and vibrant sense of being, one that van Gogh with his need for religion via the celestial realm might have found comforting.

Image: The Carina Nebula in visible light. Credit: NASA.

So, do the authors have The Answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything Else? Well… like the world in which we reside, the results are at once both clear and more complex than a single resolution can provide.

The core of the concern held by Abrams and Primack – that industrial humanity has gotten away from its original ancestral views of the heavens and needs to reconnect with its cultural roots in order to truly make it in the Universe – is one I have long agreed with. Science via technology may know far more about the true makeup and actions of the stars and other worlds in space than our ancestors could even imagine, but modern civilization and its various trappings have also made many of us less aware of what goes on in the sky than our forbearers.

This disconnect has brought us to a strange state where we have the knowledge and ability to literally reach the stars, yet only a fraction of the resources and funding from our civilization goes to space exploration and science education. This has also led us to still act as if Earth is the focal point of existence and will somehow continue to sustain humanity even as we are now over seven billion in number and climbing literally every second. In essence, many individuals are intellectually aware of our true place in the Cosmos, but culturally we are still in the huts and caves, distracted into thinking otherwise by the smooth surfaces and shiny toys in those dwellings.

With The New Universe, Abrams and Primack make a mighty and interesting intellectual effort to explain our long history with the Cosmos and reconnect us with the heavens through modern science with some religious symbolism and ideas that simultaneously try not to turn science into yet another religion in the process. This effort is an outgrowth of their earlier collaborative book, The View from the Center: Discovering Our Extraordinary Place in the Cosmos (Riverhead Books, New York, 2006), and based on their participation in the Terry Lecture Series at Yale University in October of 2009.

The authors recognize that for as much as we have evolved in knowledge and technology since first emerging from the trees and savannahs several million years ago, our biology is still deeply connected to those tribal ancestors rooted in small communities and seeing the world as both infused and controlled by the supernatural.

We are still very much social animals, loyal to the views and beliefs of our groups, which vary across the planet. Abrams and Primack not only want to unite these disparate views through modern cosmology – the Universe started with the Big Bang, almost all of the Cosmos is composed of Dark Matter and Dark Energy – but they want it done NOW.

Their urgency comes from the view that the Twenty-First Century is a pivotal point in human history. We have the comprehension and the ability to know how existence really works and the means to lift ourselves out of the tribal mindset that is eating away at our planet’s resources and wrecking Earth’s environment. However, we only have so long to use our modern skills and tools before civilization loses its literal and collective fuel along with its focus, falling into a Dark Age that our descendants may never truly recover from. Or perhaps we may even drop all the way to the extinction of our species, taking many other living residents of this planet along with us.

I tend to agree with the authors of The New Universe that we are on the edge of either greatness or doom with our global society. I think that before the end of this century, humanity has to shed those ancient cultural and even instinctual views and behaviors which make us continue to act like we are still in little disconnected villages where the collective view of the world ends at our local horizons and warring on other groups will only have consequences for the enemy. We also need to be more aware of the potential threats from beyond Earth as well, such as from the planetoids and comets that wander out Sol system which could one day strike our world and cause devastation on a global scale.

This edge we are perched upon may not have enough leeway to allow us to wake up only when impending disaster appears. Would we be able to build a Worldship to conduct a celestial rescue of at least a portion of our species, for example, if most people remain ignorant of what is in the Universe and disconnected from it and have failed to support an infrastructure in space which would be required for the construction and operation of a giant vessel for carrying many humans safely across the Milky Way galaxy for thousands of years?

One beef I have with The New Universe is their attitude towards extraterrestrial life, especially the intelligent kind. It is clear that Abrams and Primack are in the camp that says Earth may harbor the only intelligent life in all of existence (or at least this Universe), although they throw in the word “possibly” and its proper variations each time the subject of its reality is mentioned. As with the Rare Earth folks, they too think that simple organisms may dwell on many worlds throughout space, but as life becomes more complex, so too the odds of it happening, until biological evolution comes to the human species, where the odds of making more than one version of us on another planet seem astronomical – or so they claim.

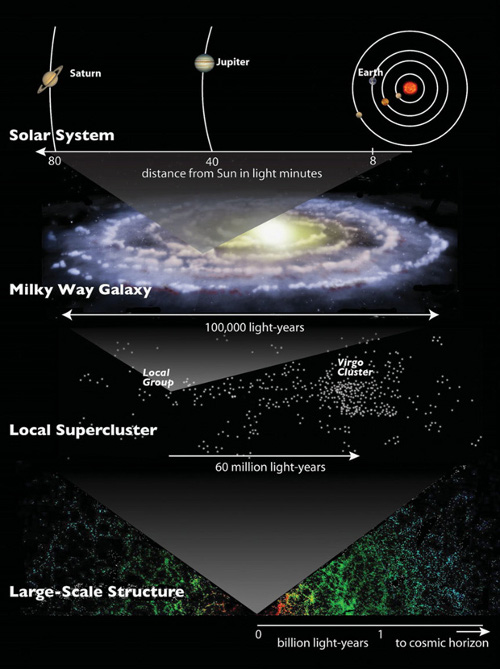

Image: Our place in the Universe. Credit: Yale University.

I get the distinct feeling that Abrams and Primack deliberately downplay the possibility for ETI to keep the focus on our species and civilization, which they already feel has had so many cosmic demotions in the last few centuries that the one which says we are just one of many intelligences in the Universe might somehow bring us down socially – despite the fact that the idea of aliens of all types has been an integral part of human society for generations now. While these fictional beings are often lacking in strong scientific integrity, they are part of our culture and they have created a level of cosmic awareness that likely did not exist in prehistoric times.

While it is true that we have no present scientific proof of extraterrestrial life and that any ETI which do exist are probably many light years from Earth, it does not help the cause of the authors to downgrade the possibility of life elsewhere, especially if they are serious about humanity becoming truly cosmically aware. The level of awareness they are asking for goes beyond just taking care of our planet. It means that our curiosity, drive, and even survival will cause us to move first beyond our home world and eventually our planetary system into the wider galaxy. Our knowledge of what exists among the 400 billion other star systems of the Milky Way contains many serious gaps, including the amount and types of alien life. ETI may or may not be an immediate concern for our species, but as students of the Universe, Abrams and Primack should know better than to dismiss something that could have a major effect on humanity in one form or another.

In regards to their views on ETI and the recent Centauri Dreams article on the hypothetical intelligence of stars, the authors discussed this subject and the possibility of galaxies and even the Universe as living entities in the FAQ chapter, which was clearly honed from the Q&A portions of their lectures and earlier book. Their answer is that galaxies are too large to be intelligent, in that it would take many thousands of years for the stars to communicate among themselves and millions of years for galaxies to talk to each other, assuming their thought waves or equivalents move no faster than light speed.

For those who wonder exactly who this book is for, the authors have said that it is essentially for everyone, while Primack also declared in one interview that The New Universe is aimed at the high school student both literally and intellectually. With the study of the heavens often being a great intellectual equalizer, educated folks of almost all ages who may be novices when it comes to astronomy and history – or who need some educational refreshers or just want our cosmological history presented in a concisely written package – will also find this work quite useful.

The fact that The New Universe is deliberately not some dry recitation of astronomy and history, makes a noble effort to reconcile the two cultures as defined by C. P. Snow, and implores its participants to care for our planetary home may ironically alienate some readers; however, the book’s title makes it clear up front what one is getting into, so the choice – just as it is with humanity when it comes to our place in the Cosmos – is ultimately yours.

The companion Web site for The New Universe, which includes among the information video presentations made specifically for the book, is here.

Hi Larry

I think that unless a Philosophy can come to grips with other possible Intelligences in the Cosmos, then it is fundamentally incomplete. You’ve managed to point out the Ptolemaic flaw in their proposal and thus I thank you for helping me steer-clear of their concept. The same goes for Biocentrism and similar parochialism that deify Life-as-we-know-it.

While we’re on the subject of opinion, Arthur C. Clarke wrote his City and the Stars and thereby forged in fiction the likely truth: Humanity is a late bloomer, and fated to travel among the stars in borrowed alien technology, and later would join the galactic races in their decision to create a pure mind of vast abilities. Said Mind developed far too fast and became insane and wrecked half the Universe before it was imprisoned inside a Black Hole. The races later decide to try again building a pure intellect, knowing in advance such a mind would need millions of years to mature and adopt a benign relationship to the universal life force and the dynamic stars.

You seek a new religion that embraces both emotion and mind which would help humanity adopt the stars as our own natural place of being…here it is….in this one book

The philosophical crafting has already been done for you, for me, for us, and that is our finest blessing. You brushed up against the truth by mentioning Aristarchus and the ancient Greeks….unfortunately too few listened to him all those centuries ago and too few saw fit to build out his ideas further. We are never handed the complete truth by a single mind. Something is always missing.

But you are all being heard clearly and recorded too. You would be amazed at the tides you are turning and the pivotal history you’re making with this one web site.

JDS

In evolutionary terms, we are still the same people as our ancestor 40,000 years ago. We won’t be changing any time soon. But as typical we can solve these issues, we always have had the ‘doom and gloom’ for centuries. What I’ve seen lately is the ego-centrism in scientific pursuits that like the turn of the 19th century, is the belief we ‘know all that is knowable’. I think it’s far from it.

James D. Stilwell said on July 9, 2012 at 10:47:

“While we’re on the subject of opinion, Arthur C. Clarke wrote his City and the Stars and thereby forged in fiction the likely truth: Humanity is a late bloomer, and fated to travel among the stars in borrowed alien technology, and later would join the galactic races in their decision to create a pure mind of vast abilities.”

LJK replies:

While there was that paper which estimated that there could be many Earthlike planets in the Milky Way galaxy roughly 1.8 billion years older than our home world (and therefore have evolved smart inhabitants who could have outdone us ages ago), there are others who think we humans may be among the first intelligent beings in the galaxy, thus the reason things seem so celestially quiet. As always, my response is: Get off your butts, build more SETI facilities (especially in space away from Earth), and start firing up those starships!

JDS then says:

“You seek a new religion that embraces both emotion and mind which would help humanity adopt the stars as our own natural place of being…here it is….in this one book.”

LJK replies:

A religion is not what I seek when it comes to getting humanity cosmically motivated. I especially do not want to see science perceived as or turned into a religion, as that would seriously defeat the entire purpose of the field, to remain objective while seeking solid facts.

I was concerned when I saw all the religious iconography in The New Universe, such as the several graphic references to the Eye of Horus (the shining eye atop the pyramid on the back of the US one dollar bill). I get what the authors were trying to do here, but I can also see how easily this can become misinterpreted.

Ironically, though, in the end it may be religion that is one of the major driving forces that gets us off Earth and into space. They could be missionaries or oppressed or disgruntled groups who no longer wish to be confined to our planet. Kind of like what happened a few centuries ago regarding Europe and the New World.

JDS then says:

“The philosophical crafting has already been done for you, for me, for us, and that is our finest blessing. You brushed up against the truth by mentioning Aristarchus and the ancient Greeks….unfortunately too few listened to him all those centuries ago and too few saw fit to build out his ideas further. We are never handed the complete truth by a single mind. Something is always missing.”

LJK replies:

That’s right, the religious types prefered Plato and Aristotle over the Ionians, in part because the latter said there was no Heavenly Father/Mother Figure and no Afterlife, just “atoms and the void.” Not very comforting to those who need a sense of security, even if it is all in their minds. Plus, telling people there is no deity/afterlife might lead the masses to think their destinies lie in their own hands, rather than via the self-appointed authority figures of this world.

JDS then says:

“But you are all being heard clearly and recorded too. You would be amazed at the tides you are turning and the pivotal history you’re making with this one web site.”

LJK replies:

That is very good to know, thank you! Never hurts to think that one is making a difference for the better around here at some level.

Sounds like an interesting read.

Definitely people can and should be encouraged to see the bigger picture and think big. Will it change us? Haven’t a clue. But it will certainly encourage people to be wiser in their social concerns (which might one day include worrying about that big space rock that’s about to hit us!)

To be honest however I have grown a little weary of the notion that ‘when an ETI is found one day it will change our very nature’. Highly unlikely. We have seen many things since the industrial age that would make learners like Socrates wish he could live forever just so that he may peruse 21st century libraries indefinitely. But we are social animals. We follow our primal instincts. And our primal instincts will get the better of us in the end. Socialising with ETIs in the (unlikely) future may make us giddy for a few decades (if not a few months) but we might soon revert to primal concerns (like how much can we gain from these ETIs). It’s only natural. The REAL challenge is to channel these primal instincts into something that’s actually constructive.

I keep telling people, a doctor knows diseases intimately but may very well choose to ignore taking care of his own health. Science may/will never guarantee utopia.

Greg said on July 9, 2012 at 10:54:

“In evolutionary terms, we are still the same people as our ancestor 40,000 years ago. We won’t be changing any time soon. But as typical we can solve these issues, we always have had the ‘doom and gloom’ for centuries. What I’ve seen lately is the ego-centrism in scientific pursuits that like the turn of the 19th century, is the belief we ‘know all that is knowable’. I think it’s far from it.”

LJK replies:

The difference between disasters in the past and the ones that became reality starting in the last century is that the ones which can happen now are likely to be far more fatal on a species level than anything humanity could conjure up before. We have biological and nuclear weapons that could quickly reduce civilization to a Dark Age as the best of the possible outcomes from their use as just two primary examples.

As for knowing everything, we are certainly a long ways off from that, I agree. Beware of hyperbole surrounding major science projects, which is often the result of a publicist or someone trying to sell their baby.

Remember how the Hubble Space Telescope was supposed to see the Universe from its very beginning? It has done a good job seeing way back in space and time, but 22 years later the Big Bang or its equivalent remains out of reach.

As the late great Richard Feynman once said, he was glad we did not have all the answers, as that would make life so boring.

I fail to see why a new cosmic perspective should change our social systems. How exactly does it change our tribalism? How will it change our view of man’s place in the global ecosystem? How does a any belief system compete with the Darwinian processes of currently practiced capitalism?

As regards dealing with ETI. I’d like to see humans deal with our intelligent animals better first. When that mentality changes, then I think we will be able to approach ETI on a firmer footing.

This is a wonderful topic, and I see it through the eye of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. At the top of the pyramid is self actualization, including acceptance of facts. I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that most of the lucky people that come to this website are near the top of this pyramid (although my bank account wouldn’t indicate this). The sad truth is at least 5 of our 7 billion neighbors are at the bottom of this pyramid; they are still scraping by for food and shelter. Obviously there won’t be any kind of global consensus on keeping our species alive for a billion years until this changes.

Having said that, I think that ultimately it’s going to be the exploitation of resources here in our solar system that is going to be the economic driver of our space technology. Once the first company gets rich mining an asteroid, the new gold rush will begin.

Ljk, we can see more in our night skys than just the moon, the classic planets, and a few thousand stars. The following are also visible to the naked eye, so I give their magnitudes.

Andromeda Galaxy 3.44

Triangulum Galaxy 5.72

Large Magellanic Cloud 0.9

Small Magellanic Cloud 2.7

Note how very bright (and hard to miss in any night sky) the LMC is.

It is also theoretically possible for the best human eyesight to view Jupiter’s moons. If any could do so in the ancient world, that would could conceivably have more that a religious application. That ability would be very useful to long distance navigation.

Greg says “In evolutionary terms, we are still the same people as our ancestor 40,000 years ago. ” And, given the timescales on which allele frequencies would be expected to change through natural selection, he should be absolutely spot on. Below I forward below evidence that he is wrong.

There is a rapid and robust trend for human societies and individuals to become more permissive and less violent by virtually any criterion that can be objectively measured for the last two thousand years (as outlined in Pinker‘s “Better Angels of our Nature“.

The Flynn effect, is a much studied and well verified effect that the ability of people to do the most g soaked IQ tests over the last hundred years has increased by about 3 points per decade.

Other effects are more negative such as the 50% fall sperm counts throughout the Western world (and more likely, everywhere) over the last century.

Greg, you’re wrong because something very interesting already appears to be happening. So my alternate warning to yours is to remember the old Chinese curse “may you live in interesting times”, and then realise: its now!

.

Rob, we are more than our genes, there’s also epi-genetics, but that’s a side bar to all this.

We still have the same instincts as our ancestors do, that hasn’t really changed much in the past 40K years, no matter how you think we have evolved genetically.

An interesting discussion. But no mention of what is surely one of the key differences between science and religion: religions offer ideas about the fate of the individual personal consciousness after death, but science is silent on this, apart from suggesting personal oblivion. (Many scientists have not held this materialist view, Freeman Dyson being one.)

I have recently blogged on how these conflicting viewpoints affect me personally: http://www.astronist.demon.co.uk/astro-ev/ae077.html

I find that I have a split personality, responding both to science-based futuristic fiction, and to a more spiritualist or mystical take on life. I doubt whether Abrams and Primack are likely to reconcile this dualism for everybody (but I do not share the pessimistic view that they need to in order to ensure human survival and prosperity).

Stephen

Oxford, UK

It seems to be a common meme that humans need to somehow work together to move into the space age. History would seem to indicate the opposite. It was the factional and warring nations of Europe that leapfrogged the monolithic Chinese society during the industrial revolution. During World War II rocketry made great strides, and it was in the context of the Cold War that humans spent a share of global GDP on space programs that has not since been equalled. Competition fuels innovation. As investment in space moves from the statist hands of government to the competitve realm of capitalist private enterprise, we are likely to see much more rapid advancement, albeit not always along the idealistic and scientific lines pursued by the likes of NASA.

Also, the idea that humans we are living in a golden age of space, and that humans will somehow lose interest in space, seems poorly supported. The arrow of progress does not always point up in all places and all times, but any student of history will note that it does always point up over the long term.

If humans do ever contact extraterrestrials, intelligent or not, it seems unrealistic to expect that a consistent, or even humane relationship can be enforced over a population of billions of humans, and potentially across many light years of space. Again, history says that while some may interact with aliens in ways that meet the approval of the readers of this blog, it is likely that many humans will do things that are immoral, exploitative, and apalling. If extraterrestrials have evolved in any way similar to humans, (and if evolution is a universal process, this seems likely, regardless of their physical form), they will do the same in their interactions with man.

Hi Larry, thanks for this excellent review, it’s convinced me to take a look at the book. It doesn’t sound like I will agree with everything they have written, but if we kept our reading to only things that we agree with then we’d end up with a rather narrow outlook on life indeed.

Certainly, contact and its consequences are going to play a huge role in any ‘cosmic philosophy’ that we may develop. Trouble is, I’m not sure we can incorporate it until the day of contact arrives because we have no idea what it is going to be. Adam Crowl is right, until we make contact any philosophy is going to have a gaping hole, but I get the impression that the authors are saying we can’t hang around to find out. We need to start moving forward as a species now; but we’re an adaptable species and if anything comes along like ET, exotic physics or unpredictable new technology then we’ll just have to adapt our philosophy to that as we go along. That’s what makes the journey so exciting!

One thing I’m a little confused over; are the authors saying we have to leave the old religions behind, or just that these religions need to adapt to what science is telling us – for the religions to transform, if you will? I really don’t think convincing people that the Big Bang happened 13.7 billion years ago is necessarily going to make them lose faith and, while I do have a lot of hang-ups about religion, in a way I don’t want us as a species to lose our philosophical diversity. As I said at the beginning, that would just end up leading us to a narrow perspective on the Universe. So maybe it’s not just one new philosophy that we’re in need of, but many to preserve that diversity. And going back to the topic of ET, contact will surely spawn many new philosophies, like Foundationism on Babylon 5.

Ljk: “Ironically, though, in the end it may be religion that is one of the major driving forces that gets us off Earth and into space. They could be missionaries (…) who no longer wish to be confined to our planet. Kind of like what happened a few centuries ago regarding Europe and the New World.”

Ljk, though I usuallly agree with your excellent sharp comments, I diverge here, for empirical reasons;

It is obvious that most if not all major religions are very, very, very geocentric in their goals and missions, and do not attach any meaning to, nor expect anything from space exploration. The heavens are at the most considered in a spiritual context, a realm where we may go after our physical passing away, or from where certain higher beings may come or have come.

I myself have often noticed among friends and acqaintances of various religions that they had no aspirations whatsoever, even a total disinterest, with regard to space exploration, let alone the settling on other planets. Even more so, this whole idea is often even treated with ridicule, contempt and outright disapproval, because, after all, god has given us the earth, we should not have pointless aspirations with regard to other worlds and expect our salvation from divine intervention, not from our own physical ‘escape’.

Although I am usually reserved with regard to religion and the like, I do agree that we may need or at least could use a new kind of ‘spirituality’, which would give some kind of ‘higher’ meaning and purpose to human long-term cosmic endeavour.

Maybe this is expressed rather well by Ervin Laszlo, when he states that through us, humans, the universe has become self-aware. Though I definitely do not endorse everything that Laszlo promotes, I remember that I was sincerely touched when I read this and it gave me a strong sense of responsibility, even a kind of urgency, with regard to our role in the universe.

Astronist (Stephen): thanks for your honesty and openness. Yes, I recognize what you say. Though I consider myself an agnostic and strongly favor a scientific world-view and approach on life in most cases, I do acknowledge a need for meaning and purpose, though not in a dogmatic, deterministic religious way.

Confession (I hope I will still be allowed to contribute to this excellent forum after this): after several years of materialistic agnosticism, I have recently read a couple of books about (research into and evidence of) reincarnation, and I must admit that they fascinated me. I my defense I add that even Carl Sagan mentioned reincarnation, particularly the ‘anomalistic’ memories of children, as one of the very few spiritual topics worth giving serious consideration and investigation.

Greg, your suggestion that the changes might be epigenetic (obviously, finding a new equilibrium level after selective pressure has been progressively removed) is wonderfully comforting. If so, these changes should soon plateau. I must admit though that I fear other mechanisms more.

One such class of changes, are where stretches of highly repetitive DNA tend to get longer each generation, as is well attested in the case of Huntington’s. Another factor is if we account for pleiotropy when we look at r type selection for the haplotype of sperm finding the egg in a species using a K type selective strategy.

But whatever such *exciting* mechanism I might postulate, I still need a killer explanation of why it was unleased only very recently. Before our times something must have been reaping off individuals at the extreme of some trait with incredible efficiency. I suggest that this factor is better maternal care allowing babies with larger heads (and their mothers) to survive. Even now there is an intense debate as to whether the explosion in the caesarean rate can all be put down to social factors.

Astronist, I loved your blog, but I can’t help feeling that it misses an even simpler truth. In a universe with much structure, a bit of this order might be due to highly repetitive elements that organise themselves by logical principles. If so, it could well be possible to create decision procedures to predict outcomes. To me, the deeper mystery is to why these *scientific principles* seem to extend a far as they do and, furthermore, do so under rules that are simple enough for the human mind to understand.

Einstein put it better than me when he said “The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is at all comprehensible.”

Ronald, re reincarnation: when he was still a schoolboy, Freeman Dyson had a similar idea, which he called “Cosmic Unity”. I have quoted the relevant part of his book in an addendum at the bottom of this page:

http://www.astronist.demon.co.uk/space-age/essays/Psychoscope.html

Rob Henry: thanks, I agree with you and with Einstein! There seems to be a circle in which our minds are made of matter, matter is made of mathematics, and mathematics is made by minds. Perhaps pointing to some unified mental-material universe rather than simplistic materialism (our minds are nothing more than atoms) or simplistic idealism (atoms are nothing more than things in my dream).

Stephen

Martin Luther wrote, “Your god is that which you fear most to lose.”

Everybody has values. Greedy corporate executives may claim to be atheists, but they still worship sex, politics, money…

One idea about the origin of monotheism is, it was to reject the idea of giving top priority to wealth and military power (Asherah and Baal).

http://www.amazon.com/Tenth-Generation-Origins-Biblical-Tradition/dp/0801816548

I look forward to more progress in science–and in society.

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2012/07/commonwealth-of-worlds-and-olaf.html

Monday, July 9, 2012

A Commonwealth of Worlds and Olaf Stapledon

Abstract…

In his 1948 lecture to the British Interplanetary Society Stapledon considered the ultimate purpose of colonising other worlds. Having examined the possible motivations arising from improved scientific knowledge and access to extraterrestrial raw materials, he concludes that the ultimate benefits of space colonisation will be the increased opportunities for developing human (and post-human) diversity, intellectual and aesthetic potential and, especially, ‘spirituality’. By the latter concept he meant a striving for “sensitive and intelligent awareness of things in the universe (including persons), and of the universe as a whole.”

A key insight articulated by Stapledon in this lecture was that this should be the aspiration of all human development anyway, with or without space colonisation, but that the latter would greatly increase the scope for such developments.

Another key aspect of his vision was the development of a diverse, but connected, ‘Commonwealth of Worlds’ extending throughout the Solar System, and eventually beyond, within which human potential would be maximised.

In this paper I analyse Stapledon’s vision of space colonisation, and will conclude that his overall conclusions remain sound. However, I will also argue that he was overly utopian in believing that human social and political unity are prerequisites for space exploration (while agreeing that they are desirable objectives in their own right), and that he unnecessarily downplayed the more prosaic scientific and economic motivations which are likely to be key drivers for space exploration (if not colonisation) in the shorter term.

Finally, I draw attention to some recent developments in international space policy which, although probably not influenced by Stapledon’s work, are nevertheless congruent with his overarching philosophy as outlined in ‘Interplanetary Man?’

“Stapledon’s Interplanetary Man: A Commonwealth of Worlds and the Ultimate Purpose of Space Colonisation” by I. A. Crawford

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1207/1207.1498.pdf

Ronald said on July 10, 2012 at 8:54:

Ljk: “Ironically, though, in the end it may be religion that is one of the major driving forces that gets us off Earth and into space. They could be missionaries (…) who no longer wish to be confined to our planet. Kind of like what happened a few centuries ago regarding Europe and the New World.”

“Ljk, though I usuallly agree with your excellent sharp comments, I diverge here, for empirical reasons;

“It is obvious that most if not all major religions are very, very, very geocentric in their goals and missions, and do not attach any meaning to, nor expect anything from space exploration. The heavens are at the most considered in a spiritual context, a realm where we may go after our physical passing away, or from where certain higher beings may come or have come.”

LJK replies:

Ronald, I was referring more to what we might consider to be cults than major religions – or as I like to call them, cults with a lot more money, members, and clout. Those are the groups most likely to first venture to the stars, though I can see the major denominations following into space once we get established in the Sol system and beyond. There will likely still be quite a call for guidance and protection from The Man Upstairs as humans move into the potentially hostile unknowns of the galaxy.

Among the real world examples of what I call cults wanting to escape the confines of Earth and human civilization are the people who built Biosphere 2, which was basically about a very rich controlling guy and his followers seeing if they could establish a colony on Mars. Another was drug guru Timothy Leary, who wanted to take his followers to a habitable exoplanets via big luxurious starships. No, he did not have any real clue when it came to that plan.

Ronald then said:

“I myself have often noticed among friends and acqaintances of various religions that they had no aspirations whatsoever, even a total disinterest, with regard to space exploration, let alone the settling on other planets. Even more so, this whole idea is often even treated with ridicule, contempt and outright disapproval, because, after all, god has given us the earth, we should not have pointless aspirations with regard to other worlds and expect our salvation from divine intervention, not from our own physical ‘escape’.”

LJK replies:

There is an old science fiction fandom quote that goes: “The meek shall inherit the Earth. The rest of us are going to the stars.” The sad truth is that a lot of people who otherwise consider themselves educated know rather little about astronomy, physics, and general science. And with society constantly focusing its collective nose on the ground and mocking education and science, this situation is not going to improve until and unless radical changes are made to our educational system, which still operates like it did centuries ago.

Ronald then said:

“Although I am usually reserved with regard to religion and the like, I do agree that we may need or at least could use a new kind of ‘spirituality’, which would give some kind of ‘higher’ meaning and purpose to human long-term cosmic endeavour.”

LJK replies:

That was the main point of The New Universe, to give a meaning and purpose to our place in the Cosmos. Of course religious folks will already declare they have a purpose beyond the terrestrial. The book is aimed at those who want meaning that elevates their emotional well being, but without a lot of religious trappings.

As I said in my review, whether they succeed or not remains to be seen, but we who are interested in space and want to see our species future in it need to speak up. Otherwise we will spend another four decades or more whining about how we haven’t gone back to the Moon since 1972 or sent any humans to Mars yet.

Ronald finally says:

“Maybe this is expressed rather well by Ervin Laszlo, when he states that through us, humans, the universe has become self-aware. Though I definitely do not endorse everything that Laszlo promotes, I remember that I was sincerely touched when I read this and it gave me a strong sense of responsibility, even a kind of urgency, with regard to our role in the universe.”

LJK replies:

I was also quite taken when Carl Sagan said something very similar in Cosmos, that “we are a way for the Universe to know itself.” You can take that literally or metaphorically, but it does have a poetic/spiritual appeal. It can also give us a sense of purpose and destiny. It may seem esoteric to many Earth-bound critters, but aren’t most religions pretty darn esoteric too, promising a future in a place that there is no solid evidence for? At least we know the wider Universe is real and attainable in our lifetimes.

An excellent example of someone actually doing something about reconnecting modern people with the heavens is the Sunwheel at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

http://www.umass.edu/sunwheel/

A former professor named Judith S. Young designed and built a carefully placed collection of large and heavy standing stones in the late 1990s to mark the rising and setting of the Sun, Moon, and certain stars through the seasons. Groups gather at the Sunwheel every solstice and equinox to mark and witness these particular events.

Personally I think every community should have their own Sunwheel. It does not have to be as elaborate as the UMass one, but it should not and cannot be something cheap and thrown together, either. Nothing like a physical presence and demonstration to make people aware and appreciate where we are in the Universe.

Like that piece on intelligent stars I read that left me speechless, I am quite unsure what to make of this one and I wade into it reluctantly (I had to pass on the other). My guess is there is a notion that if we could someone re-connect science and religion with the cosmos to the same degree our ancestors could, admittedly under very different circumstances and knowledge levels, that might lead to good things, e.g. a new inspiration for manned space flight and colonization, particularly the interstellar sort, for our survival and all that. I could be completely wrong on this, but if I’m right then I have to say I don’t buy it and I regret if I offend or annoy in laying out my objections. I think the idea completely mis-characterizes religion which is a bloody business of charismatic leaders, the grimmest group think, continuous and unwholesome obsessions with death, and not to neglect our favorite, sturm and drang sex — if there is time in all the blood and death business to squeeze it in.

Obviously, all the characteristics we now associate with scientific and technological research laboratories.

More seriously as Bertrand Russell pointed out, whenever science and religion get together science always loses and religion always win. Why are we even going there when it’s easy to see why? As soon as science starts to impinge on religion’s turf (guess who determines that?), we at once hear “Whoa there, friend! There are things science can say nothing about, know nothing about, so back off, back to your laboratory.” On the other hand, as soon as there is any scientific discovery that can be remotely correlated with religious holy writings, it’s “You see! We religionists knew it all along. I guess we really don’t need you guys, so back off, back to . . .” This is a hopelessly negative sum game. Nothing good will ever come of playing it.

Confession: at one point in my life I did try my own program of reconciliation. In my misspent youth, so I have an excuse, I read all I could of religion to make sense of it. Everyone told me, of course, I was going about it the wrong way. Religion came from the heart, not the mind. About as helpful as they got.

But when I read Tom Wolfe’s essay “The Third Great Awakening” the dynamics of religions, how they formed, how they acquired political power, and what they said about us, became clear. Not long after reading Wolfe, I read “Religion X: Shadow or Reality” a phone book size collection of raw documents on the history of a religion I prefer not to name so no one gets upset. Actually, I read the book twice I was so grossed out. Now it was really clear: the patterns and dynamics that Wolfe saw were laid out in all it’s unpleasantness. The scales at last fell from my eyes and all that. Like the dissolution of my Utopian fantasies during my decade long stay in Chicago, I came to realize that while religion had been a crucial element of humanity’s survival, it was long past time to get out and move far away from our beginnings. Easier said than done admittedly, but the conclusion was inescapable. With religion, we had long reached the point of rapidly diminishing returns.

Controversy: Of all the religions that humanity has had to endure, only one – Christianity – was just barely conducive to ongoing scientific progress. And given its current decline, once it’s gone there will be no religious/social structure left to support science. Whether what remains will be enough to keep the business going I hazard no prediction.

Yes, I am an atheist but I try not to be a jerk about it. Newton was a great man and was quite comfortable using his mind in both science and religion. I doubt there will ever again be a mind of that magnitude attempt what Newton did. Note: If you are curious about the “2060” EOW-date business (as I recall that was only one of the dates he deduced) and Newton in general, the I can recommend no better book that Richard Westfall’s, “Never at Rest.”

You might also want to try Einstein’s religious writings. Einstein gets a bad rap on this for being evasive, but I think he was clear enough: his was the God of Spinoza and while most religious people want a personal God, Einstein considered the notion silly. Putting it delicately, you can put all the teeth you have under a pillow, but no quarters will be forthcoming.

Point of agreement: I see little to dispel the notion that the human race is in a heck of jam and the odds of “A Canticle for Leibowitz”-type finale during this century are unfortunately increasing, perhaps rapidly so. I just see no reason to believe that dancing around a sundial will have any more bearing on our hopes for survival than spinning a prayer wheel. And fretting about ETIs is about as hopeless as it gets. Please, we’re on our own, science is our only guide (which is not the same thing as “hope”), and we have to carry on as adults using that mind-thing to the max.

Conclusion: I am reminded of something else that Russel said and will drop the matter with this quote:

“There is something feeble and a little contemptible about a man who cannot face the perils of life without the help of comfortable myths. Almost inevitably some part of him is aware that they are myths and that he believes them only because they are comforting. But he dare not face this thought! Moreover, since he is aware, however dimly, that his opinions are not rational, he becomes furious when they are disputed.”

In regards to my post on Olaf Stapledon and the subject thread in general:

http://etheses.nottingham.ac.uk/2403/1/The_British_Interplanetary_Society_and_Cultures_of_Outer_Space_-_final_copy.pdf

Here is a very interesting summary of Olaf Stapledon’s 1948 lecture to the BIS titled “Interplanetary Man?”, which was analyzed in a recent paper linked to above in this thread.

This is from the Dec. 1948 – Jan. 1949 edition of Fantasy Review magazine, at a cost of one shilling:

http://efanzines.com/FR/fr12.pdf

Johnq, to me that last Bertrand Russell quote of yours is double edged. It shows the folly of much reasoning that is done in religion’s name, but the fact that anyone could place any more importance than that over such a generalisation says even more about the anti-religious.

We cannot know why people have religious feelings, whether it has something to do with a strange seeming inbuilt capacity for rapture in humans, or is tied to a propensity by some to do charitable acts anonymously (incidentally, this is a property that can have no natural selection value), or a *pre-programmed* sequence that some of our brains go through to give us a near death experience. Religion can’t be dismissed as “the help of comfortable myths”, but, to me, we should be open to the possibility that it might be completely explained by science eventually.

Alternatively, and just as possibly, science might reach an endpoint with a rule of diminishing returns reducing its value, and religion retake its central spot. I could believe that this might even be so less than a hundred years from now.

And that is why I say that we should just push the message that, in our age, investment in science produces huge benefit to mankind, whereas we have difficulty giving objective measure to the benefit of religion. Not only is that sufficient, but anything stronger could prove counterproductive.

NASA has also begun to recognize the need to connect human culture to the Cosmos, at the very least to get across why they are sending spacecraft into the void:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=18702

I just watched a video where someone interviewed a cross section of people in Brooklyn and asked them if they heard about the Higgs boson. These otherwise seemingly educated, nice people living in one of the densest and most sophisticated urban centers on Earth had not a clue what it was and their guesses were wildly off target. Only one person had at least a basic idea what it was because she heard about the discovery in the news: She was rewarded by her companion calling her a nerd.

This is what we are up against even in the 21st Century. This is why so many people still cling to religion, not only because it is part of the culture they are raised in, but because our public education system is antiquated and often fails to properly engage our students in the wonders of the world around them.

Granting all this, some sense of spirituality or connectedness is needed along with appreciating the vast varieties of the Cosmos, which is what the authors of The New Universe are trying to do without losing the science along the way.

Otherwise we will continue to have people dismiss and even fear science and deeper knowledge in general for the same reason my grandmother, a rural farm girl growing up a century ago, told me that she did not care about history in high school, because it was all remote times and places and people who meant nothing to her and had no tangible connection to her rather simple and isolated life. And my grandmother was a hard working and overall intelligent woman.

Confronting the universe in the 21st century

by Sylvia Engdahl

Monday, July 23, 2012

Like most space advocates, I have long been discouraged by the slowness of our progress in becoming a spacefaring civilization. I have sought desperately for a way to combat the widespread indifference to that goal.

But is it really indifference? Several years ago I came to believe that the past four decades’ waning enthusiasm for space travel on the part of the general public is due to something deeper than that. I think, as I said then at my website, that it is a matter of unconscious fear. Recently in revising my 1974 book The Planet-Girded Suns, a history of past centuries’ view of extrasolar worlds, for republication, I became more than ever convinced that this is true—and yet I now feel that our society’s current ambivalence toward space may not be the tragedy that I once thought. In historical context, it can be seen as a natural and predictable stage of human progress.

Full article here:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2125/1

An inadequate education system and general ignorance are also to blame for the current state of affairs when it comes to space exploration and utilization.

Nicholas Campion

ncampion@CAOL.DEMON.CO.UK

To HASTRO-L@listserv.wvu.edu

Dear Hastroites,

Please note this general invitation:

CULTURE AND COSMOS: CALL FOR PAPERS

Literature and the Stars

We are inviting submissions for Vol. 17 no 1 (Spring/Summer 2013) on

Literature and the Stars. Papers may focus on any time period or culture,

and should deal either with representations of astronomy or astrology in

fiction, or studies of astronomical or astrological texts as literature.

Contributions may focus on western or non-western culture, and on the

ancient, medieval or modern worlds.

Papers should be submitted by NOVEMBER 15, 2012. They should typically not exceed 8000 words length and should be submitted to

editors@cultureandcosmos.org. Shorter submissions are welcome.

Contributors should follow the style guide at:

http://www.cultureandcosmos.org/submissions.html

Please include an abstract of c. 100-200 words.

All submissions will peer-reviewed for originality, timeliness, relevance,

and readability. Authors will be notified as soon as possible of the

acceptability of their submissions.

As from Vol. 17 no 1 Culture and Cosmos will be published open-access,

on-line, in the interests of open scholarship. Hard copy will be available

via print-on-demand.

(By the way, before anybody asks, we have been running behind schedule but

are getting up to date. As from the above issue we will have additional

editorial staff in Dr Fabio Silva and Dr Jennifer Zahrt).

Cheers,

Nick

How many Gen Xers know their cosmic address?

Source: University of Michigan

Posted Tuesday, October 23, 2012

Less than half of Generation X adults can identify our home in the universe, a spiral galaxy, according to a University of Michigan report.

“Knowing your cosmic address is not a necessary job skill, but it is an important part of human knowledge about our universe and–to some extent–about ourselves,” said Jon D. Miller, author of “The Generation X Report” and director of the Longitudinal Study of American Youth at the U-M Institute for Social Research.

The study, funded by the National Science Foundation since 1986, now includes responses from approximately 4,000 adults ages 37-40–the core of Generation X.

The latest report examines the scientific literacy of Gen Xers about their location in the universe. Miller provided Generation X participants in the study with high-quality image of a spiral galaxy taken by the Hubble space telescope, and asked them to identify the image, first in an open-ended response and then by selecting from multiple choices.

Full article here:

http://spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=38986

To quote:

“Unlike our distant ancestors who thought the earth was the center of the universe, we know that we live on a small planet in a heliosphere surrounding a moderate-sized star that is part of a spiral galaxy,” Miller said. “There may be important advantages in the short-term–the next million years or so–to knowing where we are and something about our cosmic neighborhood.”

http://arxiv.org/abs/1212.1592

Cosmology and Science Education: Problems and Promises

Authors: Helge Kragh

(Submitted on 7 Dec 2012)

Abstract: Cosmology differs in some respects significantly from other sciences, primarily because of its intimate association with issues of a conceptual and philosophical nature. Because cosmology in the broader sense relates to the world views held by students, it provides a means for bridging the gap between the teaching of science and the teaching of humanistic subjects.

Students should of course learn to distinguish between what is right and wrong about the science of the universe. No less importantly, they should learn to recognize the limits of science and that there are questions about nature that may forever remain unanswered. Cosmology, more than any other science, is well suited to illuminate issues of this kind.

Comments: 37 pages

Subjects: History and Philosophy of Physics (physics.hist-ph); Physics Education (physics.ed-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:1212.1592 [physics.hist-ph]

(or arXiv:1212.1592v1 [physics.hist-ph] for this version)

Submission history

From: Helge Kragh [view email]

[v1] Fri, 7 Dec 2012 12:33:05 GMT (501kb)

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1212/1212.1592.pdf

12 December 2012

** Contact information appears below. **

Text:

http://www.rasc.ca/news/light-pollution-report-reveals-environmental-impacts

LIGHT POLLUTION REPORT REVEALS ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

While awareness of man-made pollutants and their environmental impact may be rising exponentially, one source of contamination remains largely unaddressed. Light pollution is the wasteful and obtrusive emission of artificial light, and it can have disastrous consequences for the affected local environments. It not only disrupts animal populations, wastes energy, and ultimately degrades urban living; light pollution also blocks the night sky from astronomers and hopeful stargazers.

As part of its commitment to educate the public on this environmental threat, The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada has published “The Environmental Impact of Light Pollution and its Abatement, as a special supplement to its internationally recognized periodical, the Journal. Featuring the latest information surrounding light pollution’s causes and associated health risks, the report will also present the new technological, social, and political solutions to help us move towards a future with a more benign use of artificial light at night.

This special issue will be distributed to all RASC members, as well as to a global readership of parks, conservationists, environmentalists, Canadian astronomy clubs, government agencies and the media (to order a copy, please visit http://www.rasc.ca/jrasc).

Kate Fane

Marketing Coordinator

Royal Astronomical Society of Canada

mempub@rasc.ca

+1 416-924-7973, +1 888-924-7272

Founded in 1868, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada is Canada’s leading astronomy organization bringing together more than 4,000 enthusiastic amateurs, educators and professionals. RASC and its 29 Centres across Canada offer both national and local programming and services. The RASC’s vision is to inspire curiosity in all Canadians about the universe, to share scientific knowledge, and to foster collaboration in astronomical pursuits.

This project was funded under the Business Innovation – Print Component of the Canadian Periodical Fund (CPF).

http://www.uchospitals.edu/news/2013/20130108-universe-within.html

New book connects the human community to its cosmic roots

January 8, 2013

Neil Shubin, PhDThe 1969 “Woodstock” song by Joni Mitchell, it turns out, was onto something: “We are stardust / billion-year-old carbon.”

University of Chicago evolutionary biologist, Neil Shubin, PhD, makes that connection between astronomical events and the human species in his new book, “The Universe Within: Discovering the Common History of Rocks, Planets, and People,” a follow up to his 2008 best-seller, “Your Inner Fish.”

Where “Your Inner Fish” goes back millions of years to look at the evolutionary links between human anatomy and other animals around the world, “The Universe Within” goes back billions of years and extends out to the universe to trace the impact of cosmic events on the human body.

Shubin explains in the prologue for “The Universe Within” that it became clear while writing his first book that the creatures he initially focused on, such as fish, worms and algae, “are but gateways to ever deeper connections — ones that extend back billions of years before the presence of life and of Earth itself.”

He goes on to explain how the molecules that compose our bodies “arose in stellar events in the distant origins of the solar system.” Written inside humans, Shubin argues, “is the birth of the stars, the movement of heavenly bodies across the sky, even the origin of days themselves.”

“Every organ, cell, and gene of our bodies contains artifacts of the history of the universe, solar system and planet,” said Shubin, Robert R. Bensley Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago. “This is the story of our deep connection to the physical world as seen in stars, rocks, and the workings of DNA.”

The book, to be released Jan. 8, received advanced praise.

The Universe Within is a “fascinating, accessible tour of how life on Earth, including our own, has been shaped by many upheavals in our planet’s long history,” Sean Carroll, PhD, vice president for science education of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and professor of molecular biology and genetics at the University of Wisconsin, said in a review blurb.

Shubin’s new book, said Lawrence M. Krauss, Director of the Origins Project and Foundation Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, tells the tale, “with great authority, accuracy and a wonderfully light touch, a grand synthesis that manages to incorporate forefront research in astronomy, geology, paleontology, and genetics.”

Themes in “The Universe Within” are presented chronologically, beginning with the big bang 13.7 billion years ago, followed by the birth of stars about a million years later. Shubin then follows the story through the formation of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago, the appearance of water on Earth 4.1 billion years ago, the emergence of life 3.5 billion years ago and the rapid and ongoing evolution since then of extraordinary diversity.

Shubin presents key aspects of this vast, multifaceted and potentially overwhelming cosmic history through personal tales of scientific exploration and discovery, including his own arctic adventures. He provides brief, anecdotal portraits of the brilliant but often quirky scientists who made the connections that have shaped our understanding of the world around us, as well as their struggles to convince colleagues.

Shubin pulls together data from geology, biochemistry and anatomy to help readers gain an appreciation for the wonders of how life works.

“The first 2.7 billions years of our history was entirely in water,” he writes, “and its imprint is in every organ system in our bodies.”

But the last 300 million years have been defined by how land animals, including humans, deal with separation from water. He describes how humans form three different kinds of kidneys while in the womb. The first and most primitive is like those seen in jawless fishes, the second develops from bony fishes, and the third, the system used by mammals, appears at the end of the first trimester.

After we are born, “our body dries out with every passing year,” he notes. Newborns are “about 75 percent water, not much different from an average potato,” but adults are only 57 percent water by weight.

The magic of Shubin’s appeal “is that you can open to any page and in a paragraph or two witness an entire revelation,” says science writer Craig Childs, author of “Apocalyptic Planet.” “Shubin weaves very human stories into an earthly and universal narrative that without this book might seem too vast or too miniscule to matter.”

The hardcover (190 pages, Pantheon) will be available online and at major bookstores beginning Tuesday, Jan.8. Shubin will appear on Comedy Central’s “The Colbert Report” on Jan. 9. He will lecture in Chicago on Jan. 10 at the University of Chicago Seminary Bookstore, 5751 S. Woodlawn Ave., and at the Chicago Public Library on Feb. 11.

UCH_033321 (4)

The University of Chicago Medicine

Communications

950 E. 61st Street, Third Floor

Chicago, IL 60637

Phone (773) 702-0025 Fax (773) 702-3171

Press Contact

John Easton

(773) 702-0025

john.easton@uchospitals.edu

UCH_004401 (5)