It’s always interesting how different strands of research can come together at unexpected moments. The last couple of posts on Centauri Dreams have involved new work on Titan, and early references in science fiction to Saturn’s big moon. The science fiction treatments show the appeal of a distant object with an atmosphere, with writers speculating on its climate, its terrain, and the bizarre life-forms that might populate it. But early science fiction also proposed ways of reaching the outer Solar System, some of them echoed only decades later by scientists and engineers.

Christopher Phoenix wrote in yesterday commenting on chemist and doughnut-mix master E. E. “Doc” Smith, who when he wasn’t working for a midwestern milling company wrote space operas like The Skylark of Space on the side. Noting that Titan plays a major role in Smith’s story Spacehounds of IPC, Phoenix pointed out that the tale may be the first appearance in science fiction of beamed propulsion. This was just weeks after I had read an upcoming paper by Centauri Dreams regular Adam Crowl on interstellar propulsion concepts in which Crowl singled out E. E. Smith’s prescience, citing this same story.

The beauty of beamed propulsion is that you leave the propellant behind, thus slipping out of the noose of the rocket equation. Solar sails — using only the power of sunlight absent microwave or laser beaming — go back to the earliest days of astronautics — even Kepler had pondered the possibilities when studying comets and the effect of what he thought of as a solar wind upon their tails. Seeing that comet tails always pointed away from the Sun, Kepler homed in on the obvious analogy with seafaring vessels, wondering if fleets of space-borne ships might someday explore the Solar System. Thus his 1610 letter to Galileo:

There will certainly be no lack of human pioneers when we have mastered the art of flight… Let us create vessels and sails adjusted to the heavenly ether, and there will be plenty of people unafraid of the empty wastes. In the meantime, we shall prepare for the brave sky-travelers maps of the celestial bodies. I shall do it for the moon, you Galileo, for Jupiter.”

But sunlight drops off precipitously with distance. As Crowl noted, Smith’s concept in Spacehounds of IPC was to send energy from an installation on a planet, leaving the heavy powerplant off the vehicle by beaming intense coherent electromagnetic waves at the vessel. Here, as Phoenix did in his comment, we can cite Smith himself, who invokes Solar System locales that seemed plausible in the 1930’s, along with something called ‘Roeser’s Rays’ that supply the needed energy to the spaceships:

Power is generated by the great waterfalls of Tellus [Earth] and Venus—water’s mighty scarce on Mars, of course, so most of our plants there use fuel—and is transmitted on light beams, by means of powerful fields of force to the receptors, wherever they may be. The individual transmitting fields and receptors are really simply matched-frequency units, each matching the electrical characteristics of some particular and unique beam of force. This beam is composed of Roeser’s Rays, in their energy aspect…

…this whole thing of beam transmission is pretty crude yet and is bound to change a lot before long. There is so much loss that when we get more than a few hundred million kilometers away from a power-plant we lose reception entirely. But to get going again, the receptors receive the beam and from them the power is sent to the accumulators, where it is stored. These accumulators are an outgrowth of the storage battery…

…From the accumulators, then, the power is fed to the converters, each of which is backed by a projector. The converters simply change the aspect of the rays, from the energy aspect to the material aspect. As soon as this is done, the highly-charged particles—or whatever they are—thus formed are repelled by the terrific stationary force maintained in the projector backing the converter. Each particle departs with a velocity supposed to be that of light, and the recoil upon the projector drives the vessel, or car, or whatever it is attached to. Still with me?”

The reader may or may not be, but these early science fiction magazines were filled with long blocks of exposition as characters explained various scientific principles and fabulations to a rapt audience. Indeed, the letter columns of the science fiction pulps were filled with critiques and analyses of the various scientific ideas on display, some of them highly detailed. For more on this, there is no better source than John Cheng’s essential study Astounding Wonder (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

I’ve always been fascinated by the first appearances of concepts in the early science fiction magazines, but this one had escaped me. A good thing Adam Crowl and Christopher Phoenix were on the case! As Phoenix points out, the energy of “Doc” Smith’s imaginary ‘Roeser’s Rays’ can somehow be used to produce thrust in any direction as opposed to bouncing photons off a departing sail, which would require extreme precision to keep the sail within the collimated beam and navigating to the correct destination. Says Phoenix: “I’ve seen a lot of rocket ships and mysterious “inertial drives” and “warp drives” in early SF, but never a spaceship that rode a beam until Spacehounds of IPC, and this space opera tale could be quite significant for that fact.”

Indeed. In keeping with so much science fiction of the time, Smith’s characters are wooden, his plots lurid, but the appeal of this story is in his imagined technologies. Nor was he above tinkering with a text when asked to adapt magazine work into a novel. Crowl noticed that when you compare the 1947 novelisation of “Spacehounds of IPC” to the earlier 1931 text, Robert Goddard disappears. It was through Goddard’s efforts in liquid fuel propulsion that interplanetary development began in the original, but after Goddard’s death in 1945, the latter disappears from the ensuing novel. Interesting too that Smith always considered Spacehounds of IPC his best work, true science fiction as opposed to what he called the ‘pseudo-science’ that had animated his Skylark novels, where handwaving FTL effects are commonplace.

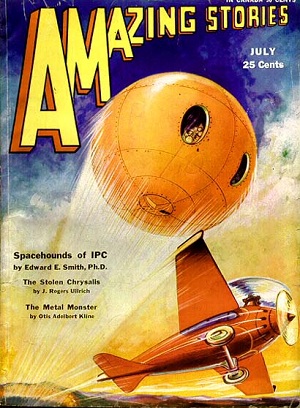

I notice that P. Schuyler Miller, long a reviewer for Astounding, regarded Spacehounds of IPC to be Smith’s most believable book, a serious upgrade over earlier work. The story was serialized in Amazing Stories beginning in July of 1931 and has had both hardcover and paperback editions in the years since. In fact, the hardcover edition of 1947 was the first book ever published by Fantasy Press, a nice collector’s item. Like Carl Wiley, who under the pseudonym ‘Russell Saunders’ wrote the first article on solar sails for a science fiction magazine (Astounding, in May of 1951), E. E. Smith dished up an SF look at beamed propulsion thirty years before the invention of the laser, a fascinating extrapolation from the technology of his era.

My current favorite early prediction is in the story “Pygmallion’s Spectacles” by Stanley G. Weinbaum in 1935. The protagonist puts on a pair of special goggles with earphones that produce a moving 3-D image with stereophonic sound, and experiences a fully immersive “movie”. This is quite close to “virtual reality”, and some of the themes are close to the idea of “The Matrix” — how do we know we are not in a greater virtual reality ourselves?

I think Tsiolkovsky had a few entries about tranmitting power to a spacecraft. I became familiar with beam propulsion through Kevin Parkin’s work using megawatt gyrotron’s for experimenting with actual prototypes. Since this equipment is powerful and it works it caught my attention immediately. I look for that fine line when a technology crosses over from “it will work” to actually accomplishing work. When I find it I hold on. I was very excited about M2P2 plasma sail technology and learned my lesson that if something is actually heavy and moving that is the only time you can believe it to be an actual contender.

Hi All

GaryChurch, I think perhaps you’re thinking of Tsander, a contemporary of Tsiolkovskii, who wrote of solar-sails and using mirrors to transmit light to space-craft. Smith seems to be first to suggest using power and momentum transmission. Of course his physics is imaginary – we have no sign of “Roeser’s” rays – but we do have laser-powered rocket designs in the literature, so he was definitely on to something.

I find it amazing that Kepler imagined solar sail spaceships in the 17th century- that makes the solar sail the very earliest method of spaceship propulsion ever conceived of- and outside of a SF story, too!! This predates work on interplanetary rockets by almost three centuries.

I agree that Spacehounds of IPC was Smith’s first work of “pure” SF- his earlier work was driven largely by a lot of hand-waving and pseudoscience, but in Spacehounds he attempted to portray a future of semi-plausible interplanetary travel (although his mysterious rays were, of course, made up). As usual, his characters were wooden and his plot lurid and action-based, in fact rather boring to a modern reader.

On Smith exploring the idea of laser-like devices- he was hardly the first to do so, and weapons that behave almost precisely like modern lasers abound in his space operas Triplanetary and Lensman, ranging from spaceship-mounted ray projectors to hand held blasters. The Standish, a semi-portable ray gun from Triplanetary, behaved just like a laser, focusing intense barely-visible reddish beams onto a target with condensing lenses and parabolic reflectors. Smith was, however, the first to imagine applying mysterious rays to propulsion in a SF story, as far as I know.

Ever since HG Wells armed his sinister Martian invaders with “heat-rays”, SF writers began portraying devices that somehow managed to focus heat, light, or other radiant energies onto targets without spreading out due to the inverse-square law, something that was not known possible until the invention of the laser decades later. In this, they were encouraged by the discovery of X-rays and radioactivity (which no doubt inspired the many other mysterious rays imagined by SF authors) and the invention of X-ray tubes and other “ray guns” for medical and scientific purposes.

Ironically, the inventors who claimed to have invented actual “death rays” around the same time periods were, in fact, attempting not to focus radiation. Some tried to conduct electrical currents to their targets through ionized air, Tesla tried to build a “particle gun” that fired microscopic particles of tungsten by electrical force (an early charged particle beam weapon), and others experimented with high frequency sound waves. Tesla stated his weapon was not a “death ray” in the slightest, as it fired microscopic bullets, and that a true “death ray” was impossible as the radiation would spread out too quickly. That was true as long as the only means of creating “death rays” available to inventors was a light bulb or X-ray tube.

Now, it is almost 2013- and where is my ray-gun? :-) In a lab, melting the odd test target. The writers didn’t anticipate that we could learn to focus deadly rays precisely on targets but be confounded by the lack of high-energy density batteries and efficient lasers…

It is too bad that it would indeed have to be Roeser’s rays when it comes to interplanetary distances. The diffraction limit is merciless. Giant structures would be required on both sides. Now, that may in certain instances be feasible and useful, but it won’t be nearly as neat as in the stories…

Nicely put Eniac. Roeser’s Rays were supposed to be of a higher frequency than “Millikin Rays” – cosmic-rays – so they’d definitely be narrow. Of course real cosmic rays aren’t “rays” as such.

We just haven’t figured this stuff out yet. doesn’t mean we won’t

hey lets figure out how to get efficient prpulstion to mars first!

“The diffraction limit is merciless. Giant structures would be required on both sides. Now, that may in certain instances be feasible and useful, but it won’t be nearly as neat as in the stories…”

Actually it will far more “neat” because it works. The prime example of something being neat but not working was the space shuttle. It certainly looked like a 1950’s spaceship. The problem was it was not in any sense of the word a working spaceship and was more a hypersonic glider with no escape system.

There is no cheap.

Gary: The space shuttle has worked plenty. Whatever its shortcomings may be, it has put the space station together, brought up Hubble, and done many other arguably useful things.

How many useful power beaming installations have been built?

The yard stick is a self-sufficient off-world colony. The reason for this colony is species survival; an insurance policy against something very bad happening on Earth. Like an engineered pathogen that would not leave survivors like an evolved one. Or an impact. This falls under the Aegis of the military so all those hundreds of billions of dollars that presently pay for boons to mankind like the B-1 bomber fleet and the V-22 Osprey can be steered toward some kind of “ROI.”

There are two ways to live in space indefinitely; on an existing body or in a several miles in diameter constructed body. To do either one requires leaving Earth orbit which the space shuttle never did even once.

How many useful power beaming installations? How many off-world colonies?

Not for the shuttle, though. That was never part of the design. The shuttle was made for transporting stuff and people to LEO, and it did that. We would have liked better, but, as they say, even the longest journey starts with a single step. Arguable, a permanent outpost is a meaningful step on the way to a self-sufficient colony, and the shuttle was instrumental in accomplishing that.

No such success was ever achieved with power beaming, not even close. Not even across the street. In my opinion, it will stay that way.

“In my opinion, it will stay that way.”

I have yet to have anyone tell me why it will not work. The math was peer reviewed and the components are all available- no unobtanium or wishalloy required. I emailed Dr. Criswell and asked him to answer the myth criticism and am awaiting his reply.

This is the same situation I often find myself in when discussing pulse propulsion on forums; so many naysayers. When we correspond I invariably find out they do not know much about bomb propulsion. But they think they know enough to say it will not work. Hmmm.

You must have not listened very carefully, I believe I have mentioned a few reasons. To recap: Giant structures, uneconomically large losses, lack of advantage for Earth-side rectennas over solar fields, and maybe a few more.

Mmmm. I, myself, have often observed the same for fusion naysayers.

“Mmmm. I, myself, have often observed the same for fusion naysayers.”

Puh-leez

A couple trillion dollars in research over the last half century has resulted in the conclusion I already reported; the only two places fusion will ever work as advertised is in a star or a bomb. Always ten years away. That amount of money invested in beaming energy would actually have stations overhead.

Most of the fusion research dollars are undercover weapons development anyway- which is not a bad thing considering that bombs are the only practical method of interplanetary travel (until a beam propulsion infrastructure is in operation).

I thought this interesting

http://nextbigfuture.com/2012/12/laser-motion-control-of-maglev-graphite.html

There are absolutely no grounds for this assertion.

” -a permanent outpost is a meaningful step on the way to a self-sufficient colony, and the shuttle was instrumental in accomplishing that.”

There are absolutely no grounds for asserting a hundred billion dollars in tin cans going in circles at very high altitude is meaninful- in any way.

“can somehow be used to produce thrust in any direction as opposed to bouncing photons off a departing sail, which would require extreme precision to keep the sail within the collimated beam and navigating to the correct destination.”

Not quite indeed, someone seems to forget about conservation laws here. when a photon “bouces” it transfers momentum, but it gives also half the momentum of the boucing when absorbed. So if it is on purpose to create the propellant with respect to E=mc^2, injecting the propulsive energy from the ship or from the beam itself, I bet the final calculation is nothing but equivalent to the boucing of photons.

“but it gives also half the momentum of the boucing when absorbed” I meant, if absorbed instead of reflected photons still give half of the momentum to the ship.