You have to like the attitude of Thomas Henning (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie). The scientist is a member of a team of astronomers whose recent work on planet formation around TW Hydrae was announced this afternoon. Their work used data from ESA’s Herschel space observatory, which has the sensitivity at the needed wavelengths for scanning TW Hydrae’s protoplanetary disk, along with the capability of taking spectra for the telltale molecules they were looking for. But getting observing time on a mission like Herschel is not easy and funding committees expect results, a fact that didn’t daunt the researcher. Says Henning, “If there’s no chance your project can fail, you’re probably not doing very interesting science. TW Hydrae is a good example of how a calculated scientific gamble can pay off.”

I would guess the relevant powers that be are happy with this team’s gamble. The situation is this: TW Hydrae is a young star of about 0.6 Solar masses some 176 light years away. The proximity is significant: This is the closest protoplanetary disk to Earth with strong gas emission lines, some two and a half times closer than the next possible subjects, and thus intensely studied for the insights it offers into planet formation. Out of the dense gas and dust here we can assume that tiny grains of ice and dust are aggregating into larger objects and one day planets.

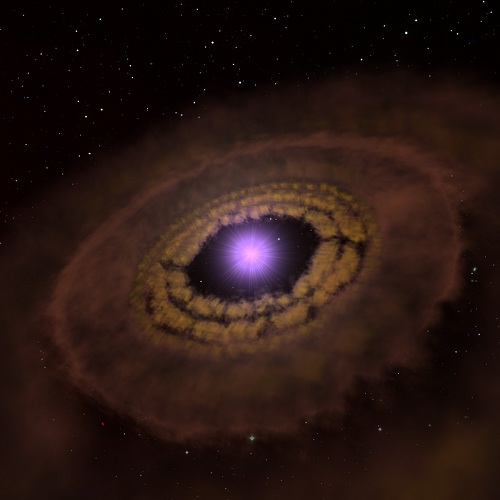

Image: Artist’s impression of the gas and dust disk around the young star TW Hydrae. New measurements using the Herschel space telescope have shown that the mass of the disk is greater than previously thought. Credit: Axel M. Quetz (MPIA).

The challenge of TW Hydrae, though, has been that the total mass of the molecular hydrogen gas in its disk has remained unclear, leaving us without a good idea of the particulars of how this infant system might produce planets. Molecular hydrogen does not emit detectable radiation, while basing a mass estimate on carbon monoxide is hampered by the opacity of the disk. For that matter, basing a mass estimate on the thermal emissions of dust grains forces astronomers to make guesses about the opacity of the dust, so that we’re left with uncertainty — mass values have been estimated anywhere between 0.5 and 63 Jupiter masses, and that’s a lot of play.

Error bars like these have left us guessing about the properties of this disk. The new work takes a different tack. While hydrogen molecules don’t emit measurable radiation, those hydrogen molecules that contain a deuterium atom, in which the atomic nucleus contains not just a proton but an additional neutron, emit significant amounts of radiation, with an intensity that depends upon the temperature of the gas. Because the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen is relatively constant near the Sun, a detection of hydrogen deuteride can be multiplied out to produce a solid estimate of the amount of molecular hydrogen in the disk.

The Herschel data allow the astronomers to set a lower limit for the disk mass at 52 Jupiter masses, the most useful part of this being that this estimate has an uncertainty ten times lower than the previous results. A disk this massive should be able to produce a planetary system larger than the Solar System, which scientists believe was produced by a much lighter disk. When Henning spoke about taking risks, he doubtless referred to the fact that this was only the second time hydrogen deuteride has been detected outside the Solar System. The pitch to the Herschel committee had to be persuasive to get them to sign off on so tricky a detection.

But 36 Herschel observations (with a total exposure time of almost seven hours) allowed the team to find the hydrogen deuteride they were looking for in the far-infrared. Water vapor in the atmosphere absorbs this kind of radiation, which is why a space-based detection is the only reasonable choice, although the team evidently considered the flying observatory SOFIA, a platform on which they were unlikely to get approval given the problematic nature of the observation. Now we have much better insight into a budding planetary system that is taking the same route our own system did over four billion years ago. What further gains this will help us achieve in testing current models of planet formation will be played out in coming years.

The paper is Bergin et al., “An Old Disk That Can Still Form a Planetary System,” Nature 493 ((31 January 2013), pp. 644-646 (preprint). Be aware as well of Hogerheijde et al., “Detection of the Water Reservoir in a Forming Planetary System,” Science 6054 (2011), p. 338. The latter, many of whose co-authors also worked on the Bergin paper, used Herschel data to detect cold water vapor in the TW Hydrae disk, with this result:

Our Herschel detection of cold water vapor in the outer disk of TW Hya demonstrates the presence of a considerable reservoir of water ice in this protoplanetary disk, sufficient to form several thousand Earth oceans worth of icy bodies. Our observations only directly trace the tip of the iceberg of 0.005 Earth oceans in the form of water vapor.

Clearly, TW Hydrae has much to teach us.

Addendum: This JPL news release notes that although a young star, TW Hydrae had been thought to be past the stage of making giant planets:

“We didn’t expect to see so much gas around this star,” said Edwin Bergin of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Bergin led the new study appearing in the journal Nature. “Typically stars of this age have cleared out their surrounding material, but this star still has enough mass to make the equivalent of 50 Jupiters,” Bergin said.

‘Extrasolar cartography’ technique could provide rough pictures of alien world.

Originally published: Jan 29 2013 – 2:00pm

By: Ker Than, ISNS Contributor (ISNS) —

Astronomers could one day create rough maps of far-away planets using information taken from starlight reflection, determining the balance of oceans, lands and overhanging clouds.

The software can take a point of reflected starlight from an exoplanet to tease apart the unique signals required to form a rough map. Developed by planetary scientist Nicolas Cowan and presented this month at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, Calif., it is inspired by a technique originally developed to distinguish between natural surfaces – such as forests – and unnatural ones like military bunkers in satellite images of Earth.

Because there is currently no telescope powerful enough to directly photograph a faraway rocky planet, Cowan tested the software on images of Earth taken from a distant vantage point in space by NASA’s Deep Impact spacecraft as part of the EPOXI mission.

Full article here:

http://www.insidescience.org/content/mapping-distant-planet-surfaces-possible/922

Slightly off-topic, but extremely interesting:

There is a new study on the extent of the Habitable Zone around main-sequence stars, based on the landmark work by Kasting et al. (1993) and updating it:

“Habitable Zones Around Main-Sequence Stars: New Estimates”, by Kopparapu, Ramirez, Kasting (again!) et al.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1301.6674

The essential outcome is that the outer edge of the HZ is about the same (a bit further out even), but that the inner edge is slightly farther out: for our solar system 0.97 (runaway greenhouse) to 0.99 (moist greenhouse) AU, instead of the 0.95 AU calculated by Kasting in 1993, “suggesting that the present Earth lies near the inner edge”

This has great implications for (future) earthlike planet searches, as well as for our own earth: it may get permanently too hot here as a result of the brightening of our sun in the course of its main-sequence even sooner than we thought.

See in particular tables 1 and 2 in the paper.

Yes, we’ll be talking about this one in tomorrow’s entry.

So this protoplanetary disk is much much heavier than ours was. More evidence that other systems may well have a lot more planets than hours. Dozens or even hundreds of Earth-sized planets, perhaps? We have only seen the tip of the iceberg, I think.

Eniac: maybe, but in case of a very massive protoplanetary disk (and/or very high metallicity) I would rather expect one or more (super) gas giants, that would accumulate much if nor most of this material.

My impression now is that a whole series of small to medium-sized planets is corellated with a not too massive proplyd.

Probably also worth investigating the binary system V4046 Sagittarii which seems to have similar properties to the TW Hydrae system.