In a 1955 letter to the British rocket scientist Val Cleaver, Arthur Clarke wrote about his view from the island then called Ceylon:

“Beautiful night last night. Southern Cross (a very feeble constellation) just above the front gate, with Alpha Centauri beside it. It always gives me an odd feeling to look at Alpha and to realize that’s the next stop.”

The next stop indeed. Cleaver was a fellow member of the British Interplanetary Society who, like Clarke, was instrumental in energizing the society after World War II. Both men served the BIS as its chairman in those years, and after Cleaver’s wartime work at De Havilland, he would go on to start a rocket division for the company and become chief engineer for the rocket division of Rolls-Royce. He is perhaps best known as the man behind the Blue Streak missile, but for those with a passion for the works of Arthur C. Clarke, he will always be remembered for his deep friendship with the man, and his energetic contribution to British thinking on space travel.

Image: Arthur C. Clarke and Val Cleaver at Warwick Castle in August of 1973. Credit: British Interplanetary Society.

Neil McAleer’s new book on Clarke is called Visionary: The Odyssey of Sir Arthur C. Clarke (Clarke Project, 2012). It’s the place to go for the background on this period, and on any period, in Clarke’s life. I call the book ‘new,’ but it’s actually a major revision and update of McAleer’s 1993 biography that adds extensive coverage of Clarke’s last fifteen years, covering a lot of material that was new to me, including insights into Clarke’s synergistic relationship with Stanley Kubrick, his reaction to the tsunami of 2004, and the almost playful way he fielded questions about his private life until a newspaper scandal based on nothing more than innuendo delayed the ceremony conferring his knighthood for two years. Throughout, McAleer’s research is exhaustive, drawing on memoirs, interviews and letters from Clarke’s many friends.

I have no hesitation in pointing you to this book if, like me, you were influenced by Clarke in your thinking about the human future in space. McAleer, an accomplished author of both fiction and non-fiction about spaceflight, met Clarke for the first time in the summer of 1988, when the latter had just been released from Johns Hopkins after a period of medical tests. The 70-year old Clarke, by then renowned for his science fiction but equally for his contributions to spaceflight including the development of the communications satellite, had been diagnosed several years earlier with amyotropic lateral sclerois (ALS), a terminal illness also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

Because the doctors found the diagnosis had been mistaken, we can assume that McAleer met Clarke at a propitious time, and he proved more than willing to let the younger writer begin a biography, armed with a contact list of 200 names that Clarke gave him. The final, revised biography is now available in several editions ranging from a beautifully crafted signed and numbered hardback, a limited edition paperback, and a soon to be available e-book edition from Rosetta Books. I think Clarke would appreciate the transition to electronic books and would find the idea of reading his work on a Kindle as natural as doing telecommunications from Sri Lanka.

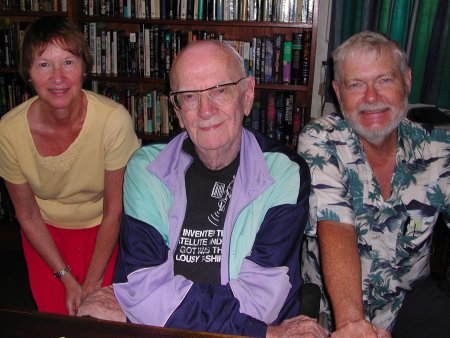

Back in 2007 I published Gregory Benford’s two-part travelogue about his journey to Asia, part of which involved flying to Sri Lanka, Clarke’s adopted home, from which Clarke routinely addressed audiences throughout the world as he continued to battle post-polio syndrome. The visit would have occurred a scant year before Clarke’s death. Here is how Benford described him:

Arthur has post polio syndrome and thus very little memory or energy. He turns 90 this December and wants to keep in touch with the outer world, mostly through the Internet. He has few friends left in Colombo. He took us to the Colombo Swimming Club for lunch, a sunny ocean spot left over from the Raj. It felt somehow right to watch the Indian Ocean curl in, foaming on the rocks, to the tune of gin and tonics — and to speak of space, that last, greatest ocean. Science fiction is to technology as romance novels are to marriage: a sales pitch. But without vision and then persuasion, little would ever happen. Arthur has always known that.

Image: Elisabeth Malartre, Arthur C. Clarke and Gregory Benford.

Vision and then persuasion — how better to describe how Arthur Clarke operated throughout a lifetime that lasted longer, as McAleer points out, than it takes Halley’s Comet to orbit the Sun? His outlook was always positive and framed in knowledge of humanity’s possibilities when enriched with technology. But he was also believer in the deep context of time and that takes me back to McAleer’s hardcover edition for a moment. Like Clarke, McAleer is a believer in long-term thinking and the symbolic acts that link us with the generations that follow us. Thus he designed the hardcover edition to last, as noted in the comments at the beginning of the book:

The challenge was to create a physical book that might survive perhaps half a millennium. With that goal in mind, the biographer researched the use of preservation-quality materials in its production—paper, ink, binding, casing, Smyth-sewn signatures and silver die stamps evoking the stars… The author intends—although he may not be able to guarantee!—that this edition’s pages will last 500 years, even outside environmentally controlled rare-archive repositories. As such, it’s hoped that this artifact will carry the artistry of Gutenberg into a future when new physical books may be far fewer.

What better tribute to a man who, in Jo Walton’s memorable phrase, wrote so eloquently about ‘the poetry of deep time’? The book that exemplified that poetry was The City and the Stars, a work that elicits so many reactions in me that I want to discuss it with reference to McAleer’s book at greater length than I have time for today. The frustration of trying to write about a man whose contributions infused both the science and literature of his time is that he was almost too big for the page to hold him. I’m going to need several days with Clarke and McAleer, continuing tomorrow with the tale first known as Against the Fall of Night.

Very nice article about Sir Arthur Clarke. Although I have to admit it was the works of Poul Anderson, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Andre Norton, etc., who affected me most as a boy. But I did read some of Clarke’s works, such as TALES FROM THE WHITE HART, with pleasure (and, of course 2001: A SPACE OYDYSSEY).

Sean M. Brooks

Thanks for the book photos. Always wondered who Val was on the dedication page of the City and the Stars. Now I know. Thanks.

Clarke was a visionary – I’ll be sure to buy the book.

I do, however, take issue with something Gregory Benford is quoted as saying :”Science fiction is to technology as romance novels are to marriage: a sales pitch.”

This is doing a great disservice to the role of science fiction in modern society. Rather than a mere “sales pitch” I think you’ll find that many (perhaps the majority?) of scientists and technologists either grew up reading and/or currently read science fiction. So, the direction that science and technologies are taking is, to some extent, being dictated by people with sci-fi concepts in mind (either at the concious or subconcious level).

Rather than a sales pitch, I would argue that science fiction is a creative basis for human exploration.

It is interesting to speculate whether Sir Arthur would have almost completely turned away from space towards the ocean without the success of his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Fortunately he didn’t, and his efforts to support the bringing of satellite communications to India and Sri Lanka must have helped the populations enormously, especially with education. We sometimes forget how unconnected the world was without comsats, now that they are common, and now being partially obsoleted by ground based optical cable and cell communication. Comsats will become important again as we use them to keep in communication with our planetary robots as we start detailed exploration of the planets.

That 1945 paper left us a fine legacy.

“Although I have to admit it was the works of Poul Anderson, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Andre Norton, etc., who affected me most as a boy.”

I started with Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars, Venus, Pellucidar (I never read a Tarzan). But it was the Lensmen series of E.E. Doc Smith that shaped my imagination concerning space.

I grew up (mostly) and after a half century on this planet I cannot seem to find any sci-fi that lights my fire anymore; I am fascinated with the reality more than any yarn. Sir Arthur was one of those people whose vision brought the world into the space age. That golden age of Moon missions may be over but there is another space age waiting to be launched. The only book by Clarke I have actually read is “The promise of Space.”

Non-fiction; and still a good read.

The Space Launch System will be lifting the big pieces to make this new space age possible. Very exciting!

Clarke was one of my faves when I was 12-13 years old. I stopped reading SF starting around 15 years old and did not return to the genre until I was in the “milieu” (life extension, cryonics, L-5, libertarianism) in SoCal during my early 20’s. At this point, I read mostly “social” SF – Heinlein, Bear, etc. These days, I read the technical stuff about about fusion, space, life extension and what not. But I don’t read much SF.

I would say that Clarke and Heinlein had more influence on me than any other SF writers.

I have always felt that Clarke’s early work was among the most poetic and lyrical that science fiction has known. Both The City and the Stars and Childhood’s End have been favorites of mine since I first read them in the the early 50’s. I’ve long since lost count of the number of times I’ve reread them.

Clarke probably had more influence on science and technology than any science fiction/science writer (and maybe any kind of writer) before or since.

I loved Rendezvous with Rama. It presented the scientific investigation as it really is: full of questions and mysteries, not full of answers and certainty.

Yes, he was a great one. Fond memory. I wish I could remember the several titles that I read. But I do remember only the name of the author. He was wise to preserve hardcopies. Who knows? Those books may become like medieval monks’ copies of Greeks’ and Romans’ hard won knowledge. Maybe help us out of a future dark age.

Don’t get me started on Clarke titles I have read… my first love was “Islands in the Sky” – read, reread and read again… and many others since.

“Rendezvous with Rama” was probably the first full-length novel I read as a kid. I was maybe 10 or 11 years old. This turned me on to the genre. I read all of Clarke’s other novels over the next few years. “The City and the Stars” is quite good, as is “Childhood’s End”. My favorites, though, were the near future stories such as “Earthlight” and “Sand of Mars”.

“Sands of Mars” was one of the few hard SF depictions of the Lowellian Mars, which is what Mars was thought to be like up until the Mariner 4 fly by in July of 1965.

My two favorite Mars novels are “Sands of Mars” and the much more recent Greg Bear novel “Moving Mars”.

After the Colliers series and the Viking Press reprints, actually those books were re-written a little my von Braun and Ley… the only book I could find when I was 13 about spaceflight was The Exploration of the Moon, with R. A. Smith, New York: Harper Brothers, 1954.

I did not know that this was an amalgamation of all the work the BIS did on their ‘moon project’ started in the late 330’s. It is a lovely book, can’t say R.A. Smith as an illustrator was up to Chesley Bonestell (who has been before or since!) but Smith was very very good.

Some one of my nerd friends at the time saw me with the book and asked if I had read Clarke’s science fiction? I found copies of The Sands of Mars (1951)[which I liked] and Prelude to Space (which I did not know was written originally in 1947)*. I found that one a strong on science, lackluster on story.

Then I was gob-smacked by Childhood’ End, I don’t think I really understood that novel until my early 20s**. Somehow I read Against the Fall of Night the same year City and the Stars came out, impressed again. I liked Earthlight better than A Fall of Moondust (which has highly regarded reputation I never have understood.)

In between we have 2001, an odd book, since it seems to have had too many rewrites, which it did!

Then finally when I thought Clarke was a goner he knocked me out of my chair with Rendezvous with Rama, which I think it his second best novel.

After Gamow’s 1,2,3 Infinity I think the finest non fiction science book of the 20th century is Profiles of the Future, this as beautiful collection of clear headed wry science writing as I know of, I keep copies around and read chapters from it every year.

*The ship Prometheus in Prelude to space, it in Kubrick’s 2001:A Space Odyssey (Updated by Ordway and Lange, there is a Lange drawing of the first stage… in a recent book). It was the Orion I and the Orion II (which we see)(there was an Orion III cargo ship too.) This two stage to orbit ship is briefly mentioned in the novel. Kubrick had neither the budget or running time to include it in the film.

** Not widely known …but Kubrick had originally wanted to make Childhood’ s End, but either could not buy the rights (if someone held them) or changed his mind. Still , he got it, it is really the end of 2001 tho re-imagined.

Your post on Sir Arthur C. Clarke touches a string in me, because I am a great fan of this great visionary. Talking about vision and Clarke, and especially with a view to interstellar travel and colonization, his book “The Songs of Distant Earth” is also very interesting. Clarke has claimed that it is his own favourite novel.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Songs_of_Distant_Earth

” The City and the Stars”, “Rendezvous with Rama”, “Songs of Distant Earth”, “2001: A Space Odyssey “, “Childhood’s End”, “Earthlight”, etc are all great works which make great reading. Will today’s Science Fiction have comparable impact on future scientists space advocates and explorers?

I enjoyed his work as well. One particularly interesting idea of his was to do with FTL: suppose we could somehow jump from .8 lightspeed (for example) to 1.2 lightspeed, without going through the intermediate velocities. That would bypass the lightspeed barrier. I wonder if anybody has ever done a serious study of the possibility.

I was sorta hoping for an April Fools’ Day entry here, but oh, well. Have a happy spring!

Dear Mr. Church:

Thanks for the flattering quoting of my own words for your note. I feel the need to stress that it was the works of Poul Anderson which made the deepest or strongest impression on me as an SF reader. And Burroughs Barsoom novels also gave me great pleasure.

And I absolutely agree with you on the need for a real space program! Both for developing our Solar System and for reaching the stars.

Sean M. Brooks

“And I absolutely agree with you on the need for a real space program!”

I offered to be a test subject for a NASA Kaldane program; I thought I made a pretty convincing case for such a radical solution to the problems of human space travel- but I guess ERB was ahead of his time.

Yes, I am joking.

Clarke’s The Sands of Mars had an interesting revelation: Apparently at the time the novel was written most astronomers did not think the Red Planet had any substantial mountains! This assumes Clarke was depicting Mars based on the latest scientific knowledge of the day. It also probably goes back to the Lowellian view of Mars as an ancient and literally worn down planet (this was before plate tectonics and continental drift).

Of course there were always contrarians like Clyde Tombaugh who thought Mars might have active volcanoes. He was right on the volcano part and who knows about the active aspect.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/05/mars-a-world-for-exploration-1959/

Chronologically, after Lester delRay, I found Clarke and Childhood’s End. Turned me upsaide down, then the Rama books, interspersed with LOTR. The breadth and depth of imagination astounded me.

Now in my 50s, I like to take my grandson Matt outside at night. I point to a star and ask him if there might be a little boy up there looking at us. I ask Matt what he thinks that little boy would want to say to us and what he would say to the little boy. He is 5, so it is a wonderful conversation.

Clarke’s depiction of Mars in “Sands of Mars” was precisely the Lowellian concept that most astronomers subscribed to at the time. In short, it was a relatively “Earth-like” with an atmospheric pressure about 0.1 atm (10% Earth’s) and temperatures cooler than Earth but not as cold as it turned out to be. It also featured plant life, which was also believed to be the case at the time. There were actually scholarly papers published in the early 1960’s on Martian “plant life”.

This perception of Mars was the scientific consensus right up to the Mariner 4 flyby in July of 1965. This flyby, as we all know now, took the famous “Moon-like” photos of Mars that proved quite a shock and disappointment to both scientists and the general public.

Dave Moody said on April 4, 2013 at 13:44:

“Now in my 50s, I like to take my grandson Matt outside at night. I point to a star and ask him if there might be a little boy up there looking at us. I ask Matt what he thinks that little boy would want to say to us and what he would say to the little boy. He is 5, so it is a wonderful conversation.”

If you do not mind my asking, what does your grandson have to say on these matters? I find the views of such young folks not only interesting but wonderfully free of bias. Okay, mostly free thanks to television, films, and video games. :^)

Abelard Lindsey said on April 5, 2013 at 21:39:

“This perception of Mars was the scientific consensus right up to the Mariner 4 flyby in July of 1965. This flyby, as we all know now, took the famous “Moon-like” photos of Mars that proved quite a shock and disappointment to both scientists and the general public.”

Which lasted until Mariner 9 showed up in 1971 and changed that perception.

If you can find the August, 1970 issue of National Geographic Magazine which has this wonderful cover story on the planets as then known and would be known when the Grand Tour was launched seven years hence (it later became Voyager 1 and 2) with incredible artwork, read what they have to say about Mars.

Thanks to Mariners 4, 6, and 7, the Red Planet is perceived as a pretty dull place, a view reinforced by several pieces of artwork that make it look like the Moon with some different colored regolith and lots of craters. And native life – forget it. It was the pre_lowellian view all over again.

‘Space Odyssey’ Author Inspires Imagination Research Center

Michael Dhar, Space.com Contributor

Date: 11 June 2013 Time: 04:53 PM ET

The creative mind behind the communications satellite and “2001: A Space Odyssey” — Arthur C. Clarke — has now inspired an academic center dedicated to studying imagination. From sci-fi speculation to neurophysiological analysis, the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination will create and sponsor multidisciplinary investigations into great leaps of human thought.

The center launched in May at the University of California, San Diego, which will operate the center in conjunction with the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation, an organization dedicated to Clarke’s legacy.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/21525-arthur-clarke-imagination-center.html

2001: A Space Infographic:

http://www.space.com/20482-2001-space-odyssey-infographic.html