I’ve always wondered how Arthur C. Clarke coped with the news he received in 1986, when doctors in London told him he was suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a terminal illness that in the States is often called Lou Gehrig’s disease. The diagnosis was mistaken — it turns out Clarke actually suffered from what is known as ‘post-polio syndrome,’ a debilitating but not fatal condition. For two long years, though, he must have thought through all the symptoms of ALS, knowing that the degenerative motor neuron breakdown could gradually sap him of strength and movement. How would such an energetic man cope with an agonizing, slow fade?

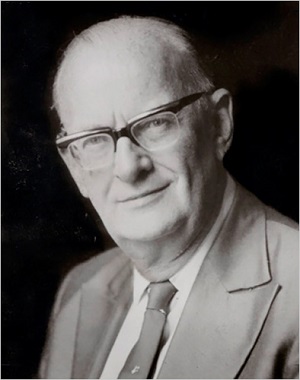

Neil McAleer’s revised biography (Visionary: The Odyssey of Sir Arthur C. Clarke) gives the answer, as recounted by Clarke’s brother Fred:

“…after the initial shock, Arthur more or less said, damn it, he’d got an enormous amount he wanted to do, and if he’s only got fifteen months to do it, he’d better whack into it. And he did whack into it, and the next year he produced four books.

“Eighteen months later he was still writing, and all the horrible things they told him might happen hadn’t happened to him. Of course they had told him all the things he should do to keep it under control—what diets to take and what exercises to do, which he very religiously did. He carried on working intensely and produced an enormous amount of work, which might have been the saving grace. If he had been the sort to say, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to die in fifteen months,’ he probably would have…”

That story speaks volumes about the man, identifying a resolve that kept him working despite his other ailments into his nineties. It also tells me that he was able to place himself mentally in a context that weighed a single human life against the broad movement of history. I think Clarke was happy to see himself as someone who instigated currents of thought, changed perspectives and launched careers. He did these things for people of all ages both by the example of his own life and by the lives he created in fiction that showed us what humanity might become.

Young Writer at Work

By the time Clarke moved from Somerset to London in 1936 he was already suffused with science fiction and in particular enraptured with Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, not to mention the second-hand copies of American science fiction magazines that were then available in England. He spoke of the ‘ravenous addiction’ these magazines inspired and the effect that Stapledon’s novel, with a time scale spanning five billion years, had upon his imagination. He was twelve years old when he first read Last and First Men, awed by its cosmic reach and its placement of the evolution of humanity against the broader backdrop of the cosmos.

Think for a moment of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Has any film ever covered a wider swath of time, from the beginnings of tool making to the apotheosis of the species in an extraterrestrial encounter? This was Clarke’s stage, but the other great discovery of his youth, David Lasser’s The Conquest of Space (1931) gave him the technology he would spend a life examining. Lasser was the founder of the American Interplanetary Society (which became the American Rocket Society and, eventually, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics). He was also, for a time, the editor of Hugo Gernsback’s Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories. If Stapledon brought Clarke the cosmos, Lasser gave the boy a focus on the attainable, the idea of space as a reachable frontier.

In London, Clarke had a tiny flat in Norfolk Square and was soon co-editing (with science fiction writer William Temple) the fanzine Novae Terrae, whose editorial sessions were so cramped in Clarke’s quarters that Temple once said “…there was hardly room for the two of us, and A[rthur]’s Ego had to be left outside on the landing.” Clarke’s nickname of Ego derives from this period when Temple and Clarke both discovered the latter’s competitive nature. I think McAleer is right in stressing, though, that Clarke’s volubility was largely the result of his enthusiasms. This was a man who loved, above all else, the communication of an idea.

Into the Remote Future

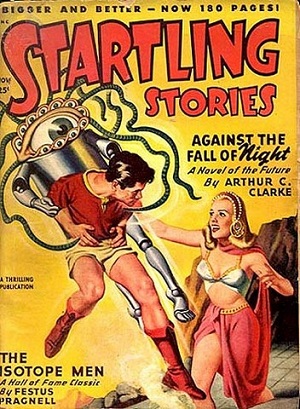

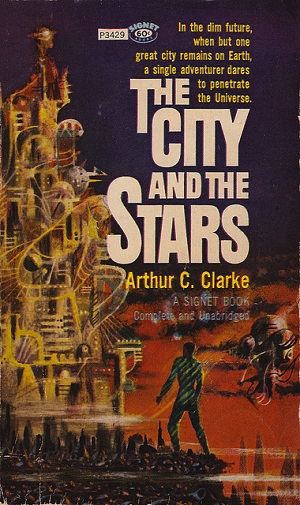

For those keeping score, Novae Terrae would soon become, under the editorship of Ted Carnell, the influential magazine New Worlds. But in the days just before World War II, while working on issues of Novae Terrae and assorted publications for the British Interplanetary Society, Clarke found time to begin developing his first novel from ideas that had come to him back in Somerset. “Against the Fall of Night” would appear in an early version in Startling Stories in November of 1948, but that hardly ended the tale. Clarke kept rewriting the story, seeing it into print as a novel from Gnome Press in 1953 and then putting it through a major revision as The City and the Stars, published in 1956.

I seldom think of Clarke as a reader of poetry, but he clearly knew his Housman:

Here, on the level sand,

Between the sea and land,

What shall I build or write

Against the fall of night?

The words are from Housman’s poem “Smooth Between Sea and Land.” Maybe the idea of long stretches of sand and a metaphorical night that comes to us all fired his imagination. I came across The City and the Stars just a few years after it was published and was mesmerized by its setting in much the way Clarke was taken with Stapledon’s Last and First Men. Here was Diaspar, the city of the far future, the only city on planet Earth, whose inhabitants moved through a high-tech monument to stasis. Nothing changes in Diaspar even as the world around it loses its oceans and becomes desert. Clarke would have much to say about the kind of inward thinking that his characters have to overcome, but the unmistakable fact about Diaspar is that the city at the end of time is also achingly, eerily beautiful.

Here’s science fiction writer Jo Walton on the book, nailing its essential allure:

The plot is quite simple. Diaspar is beautiful but entirely inward turned. Alvin looks out and discovers that there is more in the universe than his one city. He recovers the truth about human history, and rather than wrecking what is left of human civilization, revitalises it. By the end of the novel, Man, Diaspar, and Earth have begun to turn outward again. That’s all well and good. What’s always stayed with me is the in-turned Diaspar and the sense of deep time. That’s what’s memorable, and cool, and influential. Clarke recognized though that there isn’t, and can’t be, any story there, beyond that amazing image. It’s a short book even so, 159 pages and not a wasted word.

As to its author, I love the way he could never let this book go. It was, after all, his first novel, and as such it was perhaps the most deeply inspired by the reading of his youth. When he wrote a new preface to it in 1955, he noted that developments in information theory encouraged him to re-think the future course of humanity, a revision that would lead, says McAleer, to a whopping seventy-five percent new prose. The man was indefatigable; he couldn’t let go when ideas seized him, and when he had the wind behind him, no horizon was too far to strive for.

Restless Thoughts from Orbit

On the same visit to the United States in which he met Neil McAleer and learned that he did not have ALS after all, Clarke visited the National Air and Space Museum with Gregory Benford, long-term colleague Fred Durant and Hector Ekanayake, whose friendship with Clarke in Sri Lanka spanned decades. Benford noted the lack of long-term perspective in much contemporary science fiction and pointed out that The City and the Stars had been written before the discovery of DNA, so biology made no significant appearance in the story. Benford and Clarke’s Beyond the Fall of Night (1990) would be the result of that conversation.

McAleer’s biography gives the details on all of Clarke’s books, but my childhood fascination with The City and the Stars has kept me focused on the early stages of Clarke’s career in London and the ideas that began germinating both there and earlier in Somerset. The Signet paperback illustrated here is not the edition I first encountered, but I have to run it because of my love of Richard Powers, whose cover art appeared in so many paperbacks from this period. In this case, Powers’ surreal images go far toward capturing the timeless allure of the city in the desert.

The letters that McAleer has access to offer insights from Clarke’s old associates, and some new ones as well. In 2006 a British engineer named Nicholas Patrick was about to fly on a Space Shuttle mission, Discovery STS-116. He wrote Clarke to invite him to the launch, telling him he had been reading Clarke’s books since growing up in London. Due to his health problems, Clarke was unable to appear, though he wrote an enthusiastic response thanking Patrick, who replied:

“I am sad to hear that you will not be able to attend the launch, but understand completely given the circumstances. Perhaps instead, if you are willing, I might email you from orbit. “A month ago I reread The City and the Stars, perhaps my favourite book, and was again drawn by the ideas in it. Ever since I first read it, I have wanted to find an old spaceship and travel to distant suns. I shall be very happy in low earth orbit, but I don’t think it will completely satisfy me.”

And that’s the thing: Anyone who has grown up with The City and the Stars is going to find even the wonders of Earth orbit a bit tame. Clarke was always at his best as a science fiction writer when taking the long view. His characters would learn to burst free from Diaspar, but its very conception is as staggering and poetic as anything he ever wrote. From the book:

Here was the end of an evolution almost as long as Man’s. Its beginnings were lost in the mists of the Dawn Ages, when humanity had first learned the use of power and sent its noisy engines clanking about the world. Steam, water, wind-all had been harnessed for a little while and then abandoned. For centuries the energy of matter had run the world until it too had been superseded, and with each change the old machines were forgotten and new ones took their place. Very slowly, over thousands of years, the ideal of the perfect machine was approached – that ideal which had once been a dream, then a distant prospect, and at last reality: No machine may contain any moving parts. Here was the ultimate expression of that ideal. Its achievement had taken Man perhaps a hundred million years, and in the moment of his triumph he had turned his back upon the machine forever. It had reached finality, and thenceforth could sustain itself eternally while serving him.

Thus Clarke’s description of the computer that runs Diaspar free from all human intervention. What continues to confound me about Clarke is what McAleer brings out so well, the duality between an imagination capable of transcending time and the canny engineering horse-sense that spawned near-term space achievements. This is the man who dreamed up communications satellites when not dreaming of eternal cities of the far future. Tomorrow, then, let’s look at Clarke the space pioneer.

I was flipping through Prelude to Mars last night and came across a story with a dumbell shaped nuclear propelled spaceship on it’s way to Mars.

Clarke was looking into a future that never materialized. It is interesting to me that we have a transuranic, Americium, possessing properties that make it a form of the fictional element unobtanium.

We have the ability, within a decade (like Apollo), to launch human missions to the outer solar system moons. Moons that, it is generally agreed, have subsurface oceans. Perhaps that first nuclear mission will go to the dwarf planet Ceres. The way to get out there is by having the ability to deflect impact threats. We know how to build spaceships and where to go, but we seem to be more interested in threatening each other than avoiding extinction. Aliens would not be impressed.

None of these opportunities to go interesting places in interesting ways was known by Clarke. It seems that when something becomes real, or at least real enough to buy, it loses much of it’s original appeal. What I understand to be possible- right now- is far more exciting to me than any fiction. Just as in Clarke’s early days he wrote many non-fiction books; and the rockets of the 60’s more than fulfilled many of his predictions.

I always liked the commentary Clarke wrote about going from “Fall” to “City”, writing on a ship as he went to the Great Barrier Reef and other places. I hope McAleer mentions that in the book. No A/C, manual typewriter, rolling ship!

And thanks for the mentions of Stapledon. I first came to Stapledon shortly after reading “Fall”. Both Clarke and Stapledon (and J.D. Bernal, who inspired both) have stuck with me.

I always believed there were many gripping stories that could have been told from the perspective of those living inside Diaspar….then again, I’m not a child from the twenties and thirties….Enjoyed seeing again that familiar The City and the Stars book cover art….Perhaps a future Peter Jackson will see promise in telling the tale of Alvin and the Mad Mind….movies can compress time in order to make a major point…and offer a terrifying thrill….Thanks.

Looking even earlier, the novella “The Lion of Comarre” has similar themes to the later “Against..” and “The City…”. I would also argue that Clarke has explored some of the themes many times in his short stories.

While I remain a huge fan of his writing, both fiction and non-fiction, “The City and the Stars” is not my favorite novel by a long chalk. I hope you cover these in his other fiction.

“None of these opportunities to go interesting places in interesting ways was known by Clarke.” He came up with a number of drives, e.g. the black hole drive in “Imperial Earth” which transports the hero from Titan to Earth.

I also recall (probably not entirely correctly) that the BIS was not named the “British Rocket Society” after its US counterpart, because visionaries like Clarke would have happily abandoned rockets if a better alternative was developed.

“dumbell shaped nuclear propelled spaceship on it’s way to Mars.”

In Clarke’s first book “Interplanetary Flight” (1950) the dumbell atomic ship is shown in plate 8. Plate 6 has an ion drive ship towing its unshielded nuclear reactor power source on a tether.

In “The Exploration of Space” (1951) the classic R A Smith picture with the dumbell shaped interplanetary ship is shown in plate II (opp. p 15).

I think it is fair to say that the USS Discovery in “2001: A Space Odyssey” is a direct design descendant of this ship, albeit with more advanced engines.

Thanks for that very well written review.

Bob Clark

Paul,

“Think for a moment of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Has any film ever covered a wider swath of time, from the beginnings of tool making to the apotheosis of the species in an extraterrestrial encounter?”

It was known that Stanley Kubrick was an omnivorous reader, but not until later , from Christine Kubrick, did we learn that he read deeply in science fiction.

Plus no other director had the intellectual grasp of the concepts in 2001. There are great directors making (few these days) intellectual film, but no one like Kubrick.

Clarke and Kubrick were two minds on the same wavelength , as far as a science fiction Big Thinks film story in the spirit of 2001, I don’t think will ever be made again.

re Alex’ comment on ‘City’. Me too! recently, I suffered through all of the Foundation novels, including the last two nearly-unreadable ones. I listened to them on my morning constitutional on the beach, which made them barely tolerable.

Regarding ‘City’, which I also re-read (err, heard!) while walking: I couldn’t help but notice the similarity in style, which was, in a world, awful: didactic, stilted, possessing none of the grace we would find in later Clark stories. It’s one of historical interest, and perhaps to those of us who appreciate the topical treatment, but it is not one to give a friend saying “Here! try some science fiction!”, expecting the friend to find it as charming as we do.

SF has sure grown! Nowadays we have the mega-novels of Hamilton and Vinge and Reynolds and Banks, all of whom tap the rich milieu of technological progress since Clark’s time, all immensely enjoyable on levels not touched by Clark. Still, Clark has the ability to grab a simple idea, or two, vivifying a notion in a way not often rivaled.

Iain M. Banks has cancer and informed that he has months to live, maybe a year. Just finished Use Of Weapons over the Easter and now on Surface Details. This news comes on very bizzare moment. I must admit his style and depth of subject makes appreciate his talent whether one likes his books or not.

http://www.iain-banks.net/

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2303324/Iain-Banks-just-months-live-Author-announces-terminal-bladder-cancer.html

A. A. Jackson said on April 3, 2013 at 6:18:

[Paul Gilster] “Think for a moment of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Has any film ever covered a wider swath of time, from the beginnings of tool making to the apotheosis of the species in an extraterrestrial encounter?”

Well, the protagonist in the 1960 film version of The Time Traveler went all the way to the year 802,701. And if they had kept to the H. G. Wells novel, he would have time traveled to the literal end of Earth.

In Red Dwarf, the British television SF series, the main character Lister is put in suspended animation and accidentally left there for three million years.

As for great SF cinema, that era largely ended when Star Wars came on the scene in 1977. After that it was big FX budgets and simplistic plots and characters. Of course there were exceptions like Blade Runner and Moon, but Star Wars has derailed the genre for generations to come. Even a recent offering like Looper, which at least tried to be real SF, could have been a general crime drama if you took away the tine travel element – whose technical workings and why only organized crime had a hold on it is never explained.

“-that era largely ended when Star Wars came on the scene-”

Absolutely agree.

Star wars is the worst thing that ever happened to sci-fi. Brain candy for juveniles.

Lucas should feel guilty and try and undo the damage by renaking his trilogy without resorting to fantasy. Since he sold it all that will not happen.

This is a close paralell with pirate movies. The pirate era is truly an amazing study but Disney has made it into a pandering to childish fantasy.

Sad that sci-fi- which is in part responsible for some of humankinds great achievements- is now being remade into ridiculous stories that have nothing to do with predicting or creating the future.

This morning I was going through Netflix; I came across a documentary about Ian Fleming (Everything or Nothing). Funny when you compare the impact on popular culture, how do you compare how different these authors wrote. Clarke was probably just as witty as Fleming, but the audience has a different drives for ‘escapism’.

I’ve read more Clarke than Fleming, but have seen more movies from Fleming Books than Clarkes.

Broccoli is better for you than chocolate, but you’ve never seen vegetable bins next to the check out stands at the supermarket.

As the human species goes about its pedestrian affairs of daily life, Arthur C. Clarke will be remembered for his long view of the Universe. Fleming will be remembered as a very interesting note on ‘The Cold War’.

But given a chance to Time Travel and meet either one of these fellows, I confess I know how I’d like to party on a Saturday. But I know which one would really care if you got home safe Monday.