Last week’s post about the chemistry of Europa’s ocean is nicely complemented by new work on the moon’s interior by Brad Dalton (JPL) and colleagues. Like JPL’s Kevin Hand, who has been looking at the role of hydrogen peroxide in possible subsurface life there, Dalton is in the hunt for ways to learn more about the composition of Europa’s ocean. Both scientists have been using data from the Galileo mission, refining its results to produce new insights.

Usefully, the surface chemistry on Europa is affected by the charged particles continually striking the tiny world. That allows us to get a read on which parts of Europa would be the best targets for future spacecraft missions, for Dalton’s work helps us find the places where charged particles have had the smallest impact. It’s there — on parts of the leading hemisphere in Europa’s orbit — that material from within the ocean is most likely to be found in pristine condition, with the least chemical processing by incoming charged electrons and ions.

Here’s the mechanism: Europa keeps the same side toward Jupiter as it moves around the planet in its orbit. At the same time, Jupiter’s magnetic field is tugging ions of sulfur and oxygen from Io along the same path, as well as charged energetic particles that move much faster than Europa’s 3.6-day orbit. What happens is that the trailing hemisphere of Europa winds up with more sulfuric acid, apparently the result of sulfur ions bombarding the surface. Dalton’s team takes those earlier Galileo observations further by looking at five different parts of the surface.

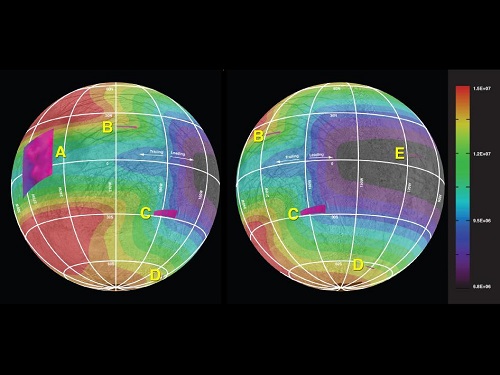

Image: This graphic of Jupiter’s moon Europa maps a relationship between the amount of energy deposited onto the moon from charged-particle bombardment and the chemical contents of ice deposits on the surface in five areas of the moon (labeled A through E). Energetic ions and electrons tied to Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field smack into Europa as the field sweeps around Jupiter. The magnetic field travels around Jupiter even faster than Europa orbits the planet. Most of the energetic particles hitting Europa strike the moon’s “trailing hemisphere,” the half facing away from the direction Europa travels in its orbit. The “leading hemisphere,” facing in the direction of travel, receives fewer of the charged particles. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Ariz./JHUAPL/Univ. of Colo.

Hydrated sulfuric acid and hydrated sulfate salts can be distinguished from water ice by the spectra gathered by Galileo’s Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer. Dalton and team are looking at the reflected light from frozen material on the surface, and comparing what they see with their models of what the particle bombardment from Jupiter and Io should produce. It turns out that sulfuric acid varies from undetectable levels near the center of the leading hemisphere to more than half of the surface materials near the center of the trailing hemisphere. The amount of electrons and sulfur ions hitting the surface shows a close correlation with this result.

So whatever chemical compounds may originally have erupted from the interior onto the surface, they’re most likely to be found unchanged on the leading edge. Says Dalton:

“The darkest material, on the trailing hemisphere, is probably the result of externally-driven chemical processing, with little of the original oceanic material intact. While investigating the products of surface chemistry driven by charged particles is still interesting from a scientific standpoint, there is a strong push within the community to characterize the contents of the ocean and determine whether it could support life. These kinds of places just might be the windows that allow us to do that.”

Europa is going to be a tough environment to work in given its high radiation environment. But work in it we must, because although oceans are also possible on Ganymede and Callisto, it’s Europa that seems to have thinnest crust, making it more likely that oceanic materials are preserved in frozen form on the surface there. To continue the investigation of Europan landing sites for future probes, another recent paper by Edward Sittler (University of Maryland) and team on plasma ion measurements near Europa makes that case that we need a 3-D model of the interactions between moon and magnetosphere to develop a global view of the electric and magnetic fields and the associated plasma environment our probes will have to work in.

The paper is Dalton et al., “Exogenic controls on sulfuric acid hydrate production at the surface of Europa,” Planetary and Space Science, Volume 77 (March 2013), pp. 45-63 (abstract). The Sittler paper is “Plasma Ion Composition Measurements for Europa,” available online at Planetary and Space Science 13 March 2013 (abstract).

if you use the size/density of the sediments in the trailing

hemisphere, and the accumulated density of Io ions on the

magnetosphere, we should get a bound on either the maximum time that

Europa has been in tidal locking exposing the trailing surface to the

magnetosphere, or either the rate of sinking/absorption of the

trailing sediments in the ice. It would seem that the only explanation

for that layer not being thick enough for hiding the underlying ice,

is that the sediments are being sunk into the ice

Paul,

Europa’s alleged ocean offers great attraction as a site extraterrestrial in our home solar system. However the immense Jovian radiation may preclude direct human exploration versus robotic exploration – at least for the foreseeable future. I certainly hope that such a huge obstacle does not prevent “manned” exploration . In any case, a mature interplanetary civilization ( which we will become I hope) may decide to that robotic submersibles are the least intrusive form to observe Europa’s inhabitants(?).

Isn’t Enceladus an even better candidate, given that it seems to be spewing its interior ocean into space, where it could be scooped up without needing a lander?

http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/jpeg/PIA14940.jpg

I like Encaledus- no rads and if you are going to fly a couple or more years to get to Europa why not go farther out? This is similar to the Mars myth; everyone seems to think it is “just close enough” for chemical propulsion. It is not. Since a nuclear propelled ship is needed anyway why not go to Ceres? This dwarf may have oceans we can explore with submarines. Mars is a rock.

What Tulse said.

Hi Paul

Europa is proving more intriguing all the time. When will we send an ice-tunneling sub? Maybe discovery and images of an alien biosphere might crack open a few minds here on Earth and end the internecine squabbling that blights even a city like Boston.

“When will we send an ice-tunneling sub?”

Sounds like Fantastic Voyage via Lem’s Solaris- maybe Asimov would have wrote the screenplay that way if he knew about the subsurface oceans on these moons.

And I was not trying to steal Tulse’s thunder by saying it first; I should have wrote “I like Encaledus also.”

Gary, I didn’t realize that Ceres was such a great target for exploration. It seems ideal as an interim step to the Jovian/Saturnian moons, since it covers so much of the science and technology goals we currently have for space exploration. The extremely low gravity and presence of water are both relevant to development of space resources from asteroids — even if Ceres itself is too far away to be a practical source of these things, working on it may provide extremely valuable experience. It’s farther than Mars, but much closer than the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, so it would be faster and easier to get to (although I don’t know what mission benefits there are of having large gravity fields so close to those moons — do they make approaching them easier and/or more efficient?).

But the most interesting thing is the possibility of an ocean on Ceres. I think that is a hugely exciting prospect, one I was unaware of until your suggestion. That may make it the closest likely candidate for life, which is an amazing possibility. At the very least, it is worth a mission to Ceres to determine if it has subsurface liquid water. Does anyone know if Dawn will be able to get any data on this with its instruments?

I believe there is a mission to ceres and the arrival year is 2015. The unmanned Dawn space craft left vesta in 2011 and is on the way to ceres.

http://dawn.jpl.nasa.gov/ask_scientist/mailToDawnScientist.asp

I explored the web site some but found no mention of proving an ocean exists. I did ask the question on their “ask a scientist” page. I will let you know Sean. Can you scuba dive? I have no experience diving under ice but….you never know.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JqRLddJwsm4

” I did ask the question on their “ask a scientist” page. ”

Joe Wise, Dawn Education and Public Outreach Manager, answered my query with a YES; they will be able to tell if there is an ocean under the surface of Ceres.

Spring 2015!

That’s excellent to hear, Gary — if it does, surely Ceres would be a top priority for an exobiology mission. (It still may be that Enceladus takes first place in the mission race, just because getting samples wouldn’t require a lander, just an orbiter with a fishing net..)

I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that the impact zone for ions is exactly where you’d find life; Life needs energy, and impacting ions creating energetic compounds could be the energy source for life. Ion-synthetic, instead of photo-synthetic.

“It still may be that Enceladus takes first place in the mission race”

I am not a scientist so I have very little interest in unmanned missions or anything having to do with me not going there. A character flaw I should work on considering I would not know anything about these intersting destination without unmanned probes.

Brett Bellmore, this mechanism of high energy production is also exceptionally good at destroying the information content imbedded in any array of complex chemicals that you could think of. For this reason life could not exist there. The best hope it that life exists just a little further below, and that these high energy chemicals are somehow rapidly transferred to safer depths. That might be a bit too much to hope… Or not.

“I am not a scientist so I have very little interest in unmanned missions or anything having to do with me not going there.”

I’ve never been to Africa, but I think elephants are terribly cool. And while I am certain that neither I nor any human being will go beyond Mars anytime in the next fifty to hundred years, I also think that unambiguous evidence of life on any of the icy objects under discussion would be of profound importance, especially if it is clear it is of non-terrestrial origin.

I have to amend my last post by stating a “stacked” pusher plate and shock absorbing system for an Orion type bomb propelled spaceship could work but then we are talking about many more launches of “slices” of this plate for assembly. So along with the plastic shielding this would involve I do not know how many HLV launches. Maybe a hundred. The fact remains that it could be done- all it takes is money and as I have said many times before, the DOD budget is proof that we CAN explore the solar system. Could evidence of complex life, such as artificial structures, allow such expenditure?

Possible. Sounds like a Kubrick movie.

“I am certain that neither I nor any human being will go beyond Mars anytime in the next fifty to hundred years,-”

This was the comment that I amended (it did not show up for some reason):

I think we will go if someone comes up with a scheme to make it happen. I commented on the other forum I visit less often that all it takes is to have pieces made in every congressional district like the V-22 Osprey and we can start packing our scuba gear. Dick Cheney could not even kill that monstrosity.

The SLS Heavy Lift Vehicle can park the pieces in lunar orbit for assembly. The best option for propulsion is Solem’s Medusa bomb propelled parachute (thus the necessity of assembling, testing, and launching the mission outside the magnetosphere). The big trick is where to get the shielding. Water derived from lunar ice is the best solution but the infrastructure to do that would take a while to build. The other way to go is RFX-1 plastic brought from Earth. We could have people on site drilling through the ice by 2025.

A fresh paper has been published regarding a new state water can be called body centered cubic (bcc). In principle it’s a state where oxygens forms a lattice where hydrogen molecules can float around and is very stable. More stable than previous exotic state called face centered cubic (fcc). The team assumes the implication is directly related to Uranus and Neptune ice properties and geology.

http://phys.org/news/2013-04-phase-dominate-interiors-uranus-neptune.html

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2338/1

Talk of an icy moon at Vegas for Nerds

by Dwayne Day

Monday, July 29, 2013

Every July a hundred and thirty thousand people descend upon San Diego for Comic-Con, an event best described as “Las Vegas for nerds.” There are thousands of events that take place both inside and outside the San Diego Convention Center over four days, some exclusive, some open to anybody who walks in. One of the more difficult to reach venues is the convention center’s Hall H, which can seat more than 6,000 people, and is the stage for most of the biggest-hyped and popular panels at Comic-Con, such as the ones where major Hollywood movies are rolled out and big name movie stars and directors unveil their new productions. Getting into Hall H often requires standing in line for many hours starting out in the early morning, or even sleeping on the lawn outside the Convention Center overnight—something you can do in your teens and twenties, but can strain the backs of people older than that.

In all my years of going to Comic-Con I’ve never tried to get into Hall H, but last week Thursday I gave it a shot and easily got into the panel for the new movie Europa Report. The movie premieres in theaters August 2, but is already available via download or on demand (see “Life and death and ice”, The Space Review, July 1, 2013).

The panel was moderated by Phil Plait, purveyor of the Bad Astronomy blog, and featured the film’s producer, director, composer, one of the actors, and two JPL scientists who served as advisers to the production.

Producer Ben Browning said that his motivation was actually to produce a movie about what first contact with alien life might actually be like. That led to Europa as the focal point.

Plait is an enthusiastic speaker, but has two vital traits as a moderator that make him superior to many of the moderators at Comic Con: he comes prepared with questions for his panelists, and he listens to what they say and is therefore able to follow up on their comments. He opened the discussion by noting that there are essentially three reasons why we explore: resources, danger, and simply to discover and see what is out there. That is true both for past exploration of the Earth as well as for space exploration today.

Director Sebastian Cordero explained that he was brought onto the production after a script had been developed and he didn’t know anything about Europa. He did not do any research before reading the script, and was impressed at how the script was based upon actual science and technology. He said that he was particularly inspired by the Al Reinert documentary For All Mankind, about the Apollo missions.

Producer Ben Browning said that his motivation was actually to produce a movie about what first contact with alien life might actually be like. That led to Europa as the focal point. Because they lacked budget, they decided to film the movie as “found footage,” which meant all the work was on a soundstage using fixed cameras. They built an enclosed spacecraft set in Brooklyn with multiple cameras inside and Cordero directed from outside the set using audio commands for his actors. This resulted in a large amount of footage because scenes were often filmed with more than one camera. That then enabled them to assemble the story during the editing process, emphasizing certain views and storylines by picking the footage.

Plait provided a little bit of explanation about Europa itself. It was first discovered by Galileo, and the “Galilean moons” of Jupiter were the first positive proof of objects circling another body in the solar system—which created a bit of a controversy between Galileo and the Catholic Church. Plait noted that Europa is the first solar system body discovered other than Earth that may have liquid water. Indeed, the water under the ice on Europa is far greater than all the water on Earth.

Composer Bear McCreary discussed the soundtrack for the film. I am a huge fan of McCreary, own many of his albums, have seen him perform in concert, and have heard him speak at several conventions, most recently at Galacticon. McCreary is a formally trained composer who understands musical theory and often incorporates a broad range of instruments into his work. He is incredibly talented and has an amazing breadth. He also comes across as somebody who loves his work and is enthusiastic about his compositions.

Plait said that although people think that scientists are frequently enraged by how inaccurately science is portrayed on film, what really annoys them is how scientists are portrayed.

McCreary explained that scoring Europa Report was difficult, and that he had developed several different approaches to the music and had to abandon all of them while trying to figure out what kind of music should accompany what purports to be a documentary of a human space mission. He said that he achieved a conceptual breakthrough when he started to think of himself as the composer hired by the fictional corporation behind the space mission—and its ostensible documentary. How would that company want to score the documentary? The documentary would be their attempt to put a positive spin on a mission that had gone very badly. Once he realized that, he managed to develop two themes for the soundtrack, one more atmospheric and the other a more traditional melody. The soundtrack album is due out soon.

Plait said that although people think that scientists are frequently enraged by how inaccurately science is portrayed on film, what really annoys them is how scientists are portrayed. Europa Report, Plait said, gets scientists right. Scientists are fascinated by their subjects of study, and in the movie they take dangerous risks so that they can collect data that they think is important.

JPL scientists Steve Vance and Kevin Hand were also on the panel and discussed their roles as science advisers. As Plait explained, often science advisers are brought onto a science fiction production to provide a thin veneer of scientific plausibility to what is above all entertainment, and scientific accuracy is not allowed to get in the way of the drama. But Vance and Hand had a significant role in developing the story and ensuring that it was not outside the bounds of reality, and in fact sometimes making the drama out of the scientific reality. Hand also added that he thought that the characters and the drama were quite good, making the movie interesting. Europa Report isn’t a science documentary.

Cordero provided an example of the science actually leading to a change in the story. Originally, the third act of the script had a key event happening on the surface of Europa. But Vance and Hand explained that this was not really plausible, but had to happen under the ice—where the action is. So they found a way to rewrite the story so that the action could happen under the ice, and Cordero said that the change actually made the story more dramatic, in addition to being scientifically accurate. Without giving it away, they were effective.

Europa Clipper illustration

The best shot for exploring Europa in the foreseeable future is not with a human mission but a robotic probe like the proposed Europa Clipper. (credit: NASA)

Browning added that Vance and Hand had emphasized how dangerous the radiation at Europa is, and this allowed screenplay writer Philip Gelatt to integrate that into the plot. When a character leaves the lander, they face the brutal radiation caused by Jupiter’s magnetic field picking up particles, accelerating them, and slamming them down into the moon’s surface. Although they did not mention it, there is a great minor plot point that demonstrates the scientific accuracy of the mission: a character mentions that the Europa lander is surrounded by a water shield to protect it from the radiation, and of course carrying all this water with them makes their lander quite heavy.

Vance and Hand had a significant role in developing the story and ensuring that it was not outside the bounds of reality, and in fact sometimes making the drama out of the scientific reality.

Karolina Wydra played one of the scientists onboard the Europa mission. She said she read Mary Roach’s book Packing for Mars before starting filming, and found it very informative (see “Review: Packing for Mars”, The Space Review, August 16, 2010). She also talked to a marine biologist about her work and was impressed how passionate the scientist was about her research. She said that the cast rehearsed extensively before filming (something that was probably necessitated by the closed-set filming method). She had to wear a 50-pound spacesuit for a crucial scene and found that she could only wear it for short stretches before having to take a break. Her character is passionate about her scientific research, so much so that she takes extreme risks, and pays for it.

Vance and Hand explained that we are still a long way from sending humans to Europa. JPL has been studying a mission called the Europa Clipper that would fly past Europa and help characterize its surface. As somebody who knows a lot about the policies and politics of planetary science, I was acutely tuned in for any statements that might create false impressions that Europa missions are in the near future. Vance and Hand did a pretty good job of managing expectations while not squashing the hopes of the audience that someday we will explore Europa in the way that it truly deserves, hopefully not as tragically as in Europa Report.

Dwayne Day served as a study director for the planetary science decadal survey. He expects to camp out overnight outside a record store in anticipation of Bear McCreary’s soundtrack for Europa Report. He can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

Beyond Hollywood: How a real-life mission to Europa would go down

Alan Boyle, Science Editor NBC News

Aug. 1, 2013 at 7:05 PM ET

“Europa Report” is one of the most realistic movies about a space odyssey since “2001,” but there’s one thing you’ll see in the film that you won’t see anytime soon in a real-life mission to Europa, Jupiter’s most mysterious moon: a human crew.

“We’re not at the stage of sending astronauts to Europa. That’s well off,” said Robert Pappalardo, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who has been working for years on plans to explore Europa. “There are things that would be wonderful to do with a person, but of course, it’s much less expensive to start out with robotic spacecraft. If we find there is evidence for life someday with a rover, then we can start talking about things that are more science-fictiony.”

Let’s face it: Few filmgoers would flock to a movie about robotic orbiters and landers heading out on a years-long trip to an icy moon of Jupiter, even if that moon might harbor life in a watery ocean deep beneath the ice. The drama comes from how people deal with the otherworldly challenges of the trip. “Europa Report” — which opens in theaters on Friday, after a weeks-long run on iTunes and cable video on demand — has that drama all the way through, wrapped up in enough plausibility to make you wonder why we’re not already on our way to Europa.

Reality bites

The reason has a lot to do with real-life constraints, as in NASA’s budget. Pappalardo noted wryly that the film’s privately funded “Europa One” mission carried a $3.6 billion price tag. “I’d take that deal,” he said. “I just don’t think it’s plausible.”

The scientific community’s once-in-a-decade assessment of planetary missions has consistently put Europa toward the top of the list for future destinations, “because it relates to the very important issue of whether there could be life elsewhere in our solar system,” Pappalardo said. But the most recent decadal survey estimated the cost of sending an orbiter to Europa at $4.7 billion. That was far too rich for a space agency already struggling with the expense of exploring Mars and building the next-generation James Webb Space Telescope.

Pappalardo and his colleagues say they can do a Europa mission for less — about $2 billion for a “Europa Clipper” space probe that would make 32 flybys from Jovian orbit. “‘Water, chemistry, energy’ is the mantra of habitability, and those are the things we’re trying to get at with a Europa reconnaissance mission,” he said.

Full article here:

http://www.nbcnews.com/science/beyond-hollywood-how-real-life-mission-europa-would-go-down-6C10823426