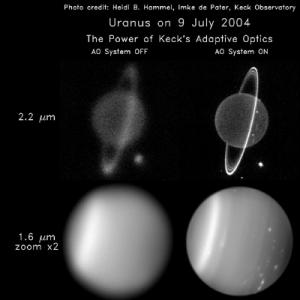

We’ve talked about adaptive optics here recently, particularly in regard to the W.M. Keck observatory complex at Mauna Kea (Hawaii). Keck’s new adaptive system essentially removes atmospheric distortion and improves data processing of the raw image. What you wind up with is a stunningly clear view, as has become apparent in new images of Uranus released by the observatory.

The images show Uranus and its ring system, first with the adaptive optics system shut off, then with it on. You can see how much more visible the rings are in the second image, but notice too the deep atmospheric cloud structure in the images on the right. More images are available at the Keck site’s article on these findings.

The images show Uranus and its ring system, first with the adaptive optics system shut off, then with it on. You can see how much more visible the rings are in the second image, but notice too the deep atmospheric cloud structure in the images on the right. More images are available at the Keck site’s article on these findings.

Image Credit: Heidi Hammel, Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO/Imke de Pater, University of California, Berkeley/ W. M. Keck Observatory.

From the Keck information, quoting a scientist who conducted a second set of observations of the planet:

Dr. Lawrence Sromovsky, principal investigator for the Wisconsin observations said, “Twenty years ago we simply couldn’t see the types of details in the outer solar system the way we can today with large, ground-based telescopes like Keck. These images actually reveal many more cloud features than the Voyager spacecraft found after traveling all the way to Uranus.”

Incidentally, the storms that show up in these Keck images would engulf the United States, but with Uranus more than 1.6 billion miles away, they’re barely detectable without such advanced imaging techniques. The clarity of the images is a reminder of how far we’ve come. Twenty years ago when we talked about viewing the outer planets, we could only imagine sharp images being taken by space-based telescopes like Hubble. Adaptive optics now offers the chance to see details that are absent almost all atmospheric distortion.

What stunning vistas lie ahead, particularly as we mount efforts to image extrasolar planets, can only be imagined, but keep the fortunes of the Terrestrial Planet Finder mission firmly in your sights. Twenty years from now, we may have equally stunning images of planets orbiting distant stars.