Back in the 1970s I ran across an essay by James Gunn called “Where Do They Get Those Crazy Ideas,” which was all about how science fiction worked and where its writers sought inspiration. I had long admired Gunn, a college professor who was developing a body of critical work on science fiction even as he continued to publish taut, interesting stories like those I had seen collected in Station in Space (1958) and The Joy Makers (1961). A story first published in Galaxy called “The Cave of Night” had particularly haunted me and led me to seek out more of his work.

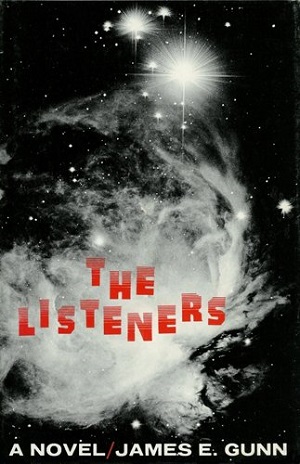

On the spur of the moment, I wrote Gunn a brief note of appreciation for the essay on writing, not thinking I would hear back from him, but sure enough a letter swiftly appeared inviting me to come to Kansas that summer, where he would be leading a science fiction workshop. That was a trip I wasn’t able to schedule, but I kept an eye on Gunn’s writing and finally, some years after its publication, sat down to read The Listeners, a 1972 novel that was actually made up of previously published stories adapted into a book using various transitional devices.

I believe this practice is known as a ‘fixup’ in the science fiction community — the field is rife with examples from Clifford Simak’s City to Keith Roberts’ Pavane — but here the effect is a bit like Dos Passos, or John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar, as the linear narrative is peppered with news reports and frequent quotes from poets and astrophysicists alike. At center is the detection of a message from an extraterrestrial civilization and its effects on the people who find the signal, as well as the society that has to integrate ET into its worldview. Gunn was inspired by Walter Sullivan’s 1966 SETI book We Are Not Alone, and in fact dedicates the volume to Sullivan, along with Carl Sagan and all those working in the SETI field.

Sagan apparently told Gunn that The Listeners had been one of the inspirations for his novel Contact, which would not be surprising given the plot premise. The novel anticipates so many of the ideas we’ve kicked around here for the last nine years that I’m surprised it hasn’t come into our discussions more often. If a message is received, do we respond to it? Would human reaction to such a signal be positive or fearful? In the case of The Listeners, we also deal with the question of motivations, for Gunn’s characters have a visual diagram sent by the aliens to work with and its contents are ambiguous, showing a humanoid creature along with the suns of a planet around the multiple star system Capella.

The system is a long way off, a 90-year round trip by radio, and the final decision to reply is motivated by a fresh decoding of what the message contains: The sending civilization is about to be destroyed. At least that’s the belief, based on a single message that was apparently sent to initiate an exchange of information, the bulk of which would take place through a colossal return message that could be expected in another 90 years, assuming humanity made the choice to answer. As you might expect, surprises are still in store, and I won’t give away what they are for those who haven’t yet read the book. Gunn’s denouement, suffice it to say, is not Sagan’s, though it does point to a future where interstellar communication will be common.

One of the pleasures of The Listeners is the interspersed quotations, from which this one, by SETI pioneer Philip Morrison, is particularly apropos given our recent discussion of galactic libraries:

Advanced societies throughout the galaxy probably are in contact with one another, such contact being one of their chief interests. They have already probed the life histories of the stars and other of nature’s secrets.The only novelty left would be to delve into the experience of others. What are the novels? What are the art histories? What are the anthropological problems of those distant stars? That is the kind of material that these remote philosophers have been chewing over for a long time…

Morrison was thinking that back in 1961, just a couple of years after the groundbreaking paper he wrote with Giuseppe Cocconi, “Searching for Interstellar Communications,” appeared in Nature (the paper is available online). Gunn has been thinking about similar issues since his first science fiction began appearing in the late 1940s (his first tale was “Communications,” which appeared in the September 1949 Startling Stories. I just missed noting his 90th birthday (July 12) but am reminded by that event that a new novel, called Transcendental, is soon to be published, a heartening reminder of the continuing imaginative gift of an author whose The Listeners rewards re-reading.

James Gunn is , finally!, Writer Guest of Honor at the 71 World Science Fiction Convention in San Antonio this year.

I may be confused but I remember a sad ending to this novel

Really enjoyed this, thank you. I haven’t read much Gunn, and The Listeners wasn’t on my radar, but it is now.

I have said in the article linked below and elsewhere here that SETI should be aiming its instruments at dead and dying suns, in the event that any species around those stars might want to transmit information about themselves as a final gesture of preservation – assuming they never achieved interstellar travel:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=9489

I have cited The Listeners as a prime example of this. The ending is only sad if the aliens never succeeded in transmitting their culture and knowledge to other beings to preserve and carry on their legacy. Something we should think about for ourselves, especially since we have a number of ways of disappearing long before our Sol goes to its red giant stage.