The MACH-11 program (Measurements of 11 Asteroids and Comets Using Herschel) uses data from the European Space Agency’s space-based Herschel observatory to look at small bodies that are targeted by our spacecraft. With the Dawn mission on its way to Ceres, the Herschel data have now revealed the existence of water vapor on the dwarf planet. To my knowledge, this is the first time water vapor has been detected in an asteroid, or I should say, an object that used to be considered an asteroid before the International Astronomical Union decided to re-classify it because of its large size.

Herschel ran out of coolant in the spring of 2013, but not before making a series of observations of Ceres in the two previous years that show a thin water vapor atmosphere. As with so many of our missions (Kepler comes immediately to mind), we still have plentiful data to look through. In this case, we’ll be examining the increasingly fuzzy distinction between asteroids and comets as we try to figure out precisely what is happening on Ceres. Dawn’s investigations, with arrival in March of 2015 and studies continuing all that year, will obviously provide a much closer look.

Carol Raymond is deputy principal investigator for Dawn at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

“We’ve got a spacecraft on the way to Ceres, so we don’t have to wait long before getting more context on this intriguing result, right from the source itself. Dawn will map the geology and chemistry of the surface in high resolution, revealing the processes that drive the outgassing activity.”

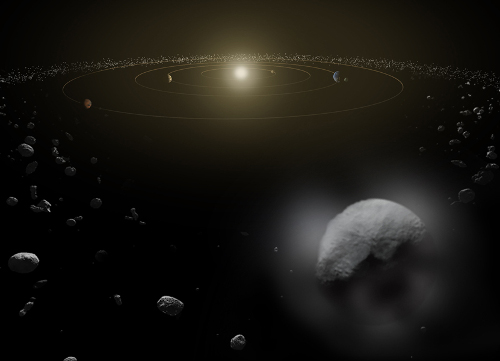

Image: Dwarf planet Ceres is located in the main asteroid belt, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, as illustrated in this artist’s conception. Observations by the Herschel space observatory between 2011 and 2013 have revealed the first unambiguous detection of water vapor around an object in the asteroid belt. Credit: JPL/Caltech.

Finding water vapor is not totally unexpected, given the long-standing assumption that Ceres contains a mantle of ice in its interior, one that may include as much as 200 million cubic kilometers of water, more than the amount of fresh water on Earth. Herschel’s work in the far infrared is what it took to make the call, complicated by the fact that the signature proved to be elusive. This JPL news release notes the emerging view that Ceres releases water vapor in plumes at about 6 kilograms per second when orbiting closer to the Sun, while remaining frozen tight when further out.

Thomas Müller (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics) discusses the finding in an MPE release:

“The intensity of the water line is linked to certain dark regions on the surface; these are either warmer areas or craters where an impact has exposed some layers of ice deeper down. Moreover, we were able to track how the amount of water changes along the asteroid’s way around the sun: if it passes nearer to the sun the water signature increases and then decreases again in the more remote sections of its orbit.”

Dawn will have specific targets to examine when it arrives thanks to the Herschel work, because the space observatory was able to see how the strength of the water vapor signature varied over time as Ceres spun on its axis. Those dark areas that Müller talks about had also been identified by earlier Hubble observations, and those of ground-based telescopes as well. Clearly, we’ll count on Dawn to teach us a lot more about them and how they operate, just as we used Cassini to investigate the geyser activity on Enceladus. The plumes of Ceres are going to get plenty of attention in the year ahead.

This is still a bit of an odd finding, Where is the energy coming from to

maintain a liquid sub-surface. Jupiter is pretty far from Ceres, (similar to

the distance of Mars Aphelion to our Sun) And Mars is too small and far to have much tidal influence (14o Mmi on avg dist). As far as we know Jupiter’s gravity is not enough to disturb Callisto surface very much, how

could it influence Ceres so much.

Compared to the Gallilean satellites, Ceres is small potatoes, I doubt there is enough of a core to get much heating from radioactive decay.

Maybe it’s the composition of the Ice, it’s not that far from the sun it might be a thin cap, if it’s powdery comet like then mild tidal action might break it up. also Maybe the ocean is Extremely salty and there is just enough tidal activity to circulate the ocean and keep it from freezing out. If I were on the DAWN mission team I’d be a bit piqued that another spacecraft made a major finding just as I was getting there, the Robert Falcon Scott treatment.

Could these vapour plumes be due to ice collecting on darker areas during the ‘colder’ distances from the sun and then them off gassing due to the warmth of been closer in during Ceres’s orbit around the Sun. Ceres polar regions are very cold and are analogous to the frost line between Mars and Jupiter and are <120 K at high latitudes [7].

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2013/pdf/1655.pdf

RobFlores said on January 23, 2014 at 12:49:

“This is still a bit of an odd finding, Where is the energy coming from to

maintain a liquid sub-surface.”

Perhaps Ceres has a moon or two tugging upon it. Or we will discover that you do not need to be a totally massive world to have your own active geology.

“If I were on the DAWN mission team I’d be a bit piqued that another spacecraft made a major finding just as I was getting there, the Robert Falcon Scott treatment.”

This is a scientific mission, not a geopolitical race such as Apollo. The Dawn team is likely very grateful for this pre-arrival discovery from Herschel. They will want all the information they can get so that the probe does not literally run into any surprises that might end the mission prematurely. This will include finding out if Ceres has any moons or perhaps even a ring. Do not scoff, I well remember when it was thought only Saturn could have a ring of debris, or that a planetoid with a moon was considered improbable. Or active volcanoes on Io.

I know one thing (or I hope at least), when the powers that be finally appreciate the resource value of Ceres and other such worlds, we will no longer be whining about a lack of funds for our space programs any more.

You may wish that space will not get turned into a celestial mining pit, but it should be clear after five decades that pure science is not reason enough to get us a permanent foothold in the Sol system and beyond. Apollo happened because two superpowers were having a muscle flexing contest, but we got a lot of lunar science and rocks out of it in the process. And the Moon is still intact.

@RobFlores – why would a subsurface liquid water ocean be needed to generate a thin water atmosphere? Wouldn’t sublimation of the exposed ice be sufficient? If extra energy is needed, what about small meteoroid impacts? After all, the LCROSS impact on the moon generated detectable water vapour from the ice present.

I imagine Ceres a bit of an hybrid between Europa and Mars and therefore very interesting. It is surprising to see any activity though. I was reading that it seems to be happening over darker areas and it seems to be related to the Ceres’ distance from the sun.

The low gravity should make landers, rovers and even sample return missions quite possible : an interesting, feasible alternative to the overexplored Mars for other countries like China, Russia and India.

ljk, I could not agree more. One thing that screams to my attention is rocket fuel, LOX-H2 made insitu at Ceres. Great for a interplanetary civilization. The hydrogen could eventually be used for nuclear fusion powered space arks to other stars when fusion rocket technology matures.

Comet or Asteroid? Herschel Space Observatory Detects Water Outgassing on Dwarf Planet Ceres

By Leonidas Papadopoulos

A new study published online in the weekly scientific journal Nature on Jan. 22 reports on observations made by the Herschel Space Observatory of water vapour seen coming out of the largest member of the asteroid belt: dwarf planet Ceres.

In the past, the Solar System seemed to be a tidy and well-organised place, with many families of objects neatly grouped together in different and distinct categories. There were planets and moons, comets and asteroids. But the nature of scientific discovery is the constant replacement of old knowledge with new, that most of the time leads to a major re-thinking and change of our established view of the Cosmos. Akin to this perpetual process of change, newer observations with modern ground- and space-based instruments have blurred the line between different families of objects.

Such examples include the discovery of objects nearly as big as Pluto in the Kuiper Belt and the more recent discovery of a comet-like asteroid located in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Now, another member of the asteroid family, the 950 km-diameter dwarf planet Ceres, can be added to the list.

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=50333

@RobFlores and Enzo

I don’t see any mention for a need of liquid sub-surface ocean

Wikipedia says that surface temperatures on Ceres are estimated to reach -38Celcius when the sun is overhead, and in the vacuum of space, some of the exposed ice would be able to sublime into water vapour at these temperatures

The plumes on Enceladus have been a lot of fun for the scientists on the Cassini mission, I wonder whether Dawn carries the same instrumentation to take advantage of these plumes

About the potential for landers and rover, I think so too, and often wonder whether Ceres will take over from Mars in the front stage for this kind of exploration

Now that we’ve an excellent design, lets start mass producing “Curiosity” type rovers to land them at interesting locations; Ceres, Enceladus, Mercury poles, Titan, etc.

If you click through to the original paper, you’ll find that they offer two possible explanations. Here’s the money quote:

“The measured water production is two orders of magnitudes higher than is predicted from a model of sublimation maintained from water supplied from the interior of Ceres. In addition, the water activity is most probably not concentrated on polar regions, where water ice would be most stable. We propose two mechanisms for maintaining the observed water production on Ceres. The first is cometary-type sublimation of (near) surface ice. In this case the sublimating ice drags near-surface dust with it and in this way locally removes the surface layer and exposes fresh ice. Transport from the interior is not required. The second mechanism is geysers or cryovolcanoes, for which an interior heat source is needed. For Jupiter’s satellite Io and Saturn’s moon Enceladus the source of activity is dissipation of tidal forces from the planet. That can be excluded for Ceres, but some models suggest that a warm layer in the interior heated by long-lived radioisotopes may maintain cryovolcanism on Ceres at the present time.”

— If you go and look at their references, you’ll see that both of these models are plausible but speculative. So we don’t know! It could be either of these, or something driven by impacts, or something else.

Doug M.

Incidentally, the estimated flux of 6 liters/second is theoretically sustainable over astronomical time. If maintained without stop for millions of years (almost certainly not the case, but if), it would cause Ceres to lose just 0.2% or so of its mass every billion years. So it’s at least hypothetically possible that we’re looking at a long-term or regularly recurring phenomenon.

One other wrinkle: in theory, some of this stuff could recondense back on Ceres, in colder regions like crater bottoms or the poles. The technical term for this is “volatile transport”, and we see it in action in places like Callisto. (That’s why most of the craters on Callisto are sort of faded and slumped and blurry.) If even 1% of the lost water was recaptured as frost, then ice would be accumulating at the caps the rate of over a micron per year — slow, but adding up to over a meter every million years.

The counterpoint to this is that as far as we can see there are no bright deposits of frost on Ceres’ surface. Fresh water ice is bright, and Ceres is very dark — one of the darkest objects in the inner solar system, with an albedo of around 0.06, comparable to fresh asphalt.

On a pure sublimation model, you’d expect at least a little recapture. So, are we looking at geysers here? Then how are they being heated? Or is there sublimation, but in some way that discourages recapture? Or is there sublimation and recapture, but with some unknown process rapidly darkening the recondensed ice? Questions abound.

Doug M.

Another point to remember is that just because it’s being called “ice” it doesn’t have to be 100% water ice. It could be a clathrate hydrate (methane, or C02 or some other volatile gas in an icy shell) that releases its contents (and some water) at much lower temperatures than just plain water ice.

Always good to do an arXiv search BEFORE posting. This article talks about clathrates on Ceres:

“On the composition of ices incorporated in Ceres”

Mousis, Olivier; Alibert, Yann

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 358, Issue 1, pp. 188-192.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/0501118v1.pdf

Comet Piazzi?!

Frosts from re-freezing after sublimation had been suspected for years, Doug M, as we have seen significant brightness changes. It’s good to see it confirmed. Though cryovolcanism would be cool…

Things are getting interesting. Ceres may turn out to be the hottest piece of real estate in the Solar System because of location. You may need no more technology than a large hot water heater and an electrolytic conversion plant to support a surface expedition and refuel a rocket to anywhere else between the Sun & the Jovian system.

If Ceres turns out very wet, we may want to send out a bathyscaphe?

With it’s dwarf planet gravitation and massive slush shelves, an undersea complex might be better than an orbital habitat?

If we could authorize an Orion drive… we could just strap on our current nuclear submarine designs and do some awesome exploration!

Ceres could be the easiest place to settle in the Solar system?

@Adam January 27, 2014 at 3:00

‘Frosts from re-freezing after sublimation had been suspected for years, Doug M, as we have seen significant brightness changes. It’s good to see it confirmed. Though cryovolcanism would be cool…’

Ceres will most likely be an ice rich world with a dark dust covering because of the constant rain of particles from the asteroid belt. The sun could warm the dust in craters that have had water vapour re-freeze in their shadows and low angled slopes leading to off gassing as the world nears the sun.

Asteroids with Comet-Like Orbits: Elements and Positions:

http://www.physics.ucf.edu/~yfernandez/lowtj.html

@Tom

I’m very interested in the question of where the easiest or most logical places to settle in the solar system are. I’ve been doing a bit of reading about it recently and don’t think that Ceres would be settled first, second or third, but to paraphrase one of the above posters in the long run it would be “The Saudi Arabia for the outer solar system”.

First it makes more sense to colonize various points in the inner solar system. I think things would go in this order:

1. LEO (ticked off already)

2. Peaks of eternal light on the moon’s poles

3. Earth-Moon Langrange 1

4. Phobos and perhaps also Deimos. A space elevator from Phobos-Mars lagrange 1 would be very good for the next stage:

5. Mars

Ceres would come one or more steps after Mars.

Colonization need not include humans initially, but must include a permanent robotic presence that produces fuel and builds infrastructure that facilitates the colonization of the next point of expansion.

What do other commenters think?

I’m not sure about the sequence of 2 & 3 in my list, i.e. whether or not it would be better to have a presence at EML1 prior to having a presence on peaks of eternal light

Re 2., there are similar peaks on Mercury, where you have extremes of solar radiation and cold in close proximity, with reserves of ice. So, abundant solar energy, water, mineral resources.

The downside is getting there. No atmospheric breaking available.

The thing is that after Mercury there are no more destinations in that direction, development of mercury perhaps doesn’t help open up any future destination so I didn’t put it in the list above. Ceres and a further vast number of destinations can be opened up by successive colonisation and establishment of refuelling points at LEO, EML1, and then Deimos or a Sun-Mars Lagrange point.

First refuelling stations in the Earth-Moon at LEO and EML1 could be provided with fuel produced on the moon’s peaks. Even for LEO, Delta-V requirements from the surface of the moon are much less than from the surface of the Earth, thanks to aerobraking LEO is reachable from the lunar surface with are just 3.2 km/s, compared to 9.5km/s from the Earth’s surface

But indeed you are right that going in the sunwards direction there are the peaks on Mercury have abundant resources. Also the 50km altitude clouds of Venus are very interesting for offering the most Earth-like conditions anywhere else in our solar system (gravity close to 1G, atmospheric pressure 1 bar, air temperature close to room temperature)

Mercury might be a good place to locate the powerful lasers needed to push solar sail missions to other star systems. They would have lots of solar power to tap into.

Mercury might also make great building material for the Dyson Shell or Matrioshka Brain:

http://www.enthea.org/planetp/mbrain1.html

This paper describes the use of that planet for building a Dyson Shell or Swarm, embedded in a fascinating discussion of how an advanced species might travel from one galaxy to another:

http://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/intergalactic-spreading.pdf

Over 70 percent of Mercury’s interior is a core composed of iron. Add in a really close Sol for lots of solar power and you have one heck of a resource site.

Lionel: Near Earth Asteroids have much more favorable delta-V than the moon, and will likely be the first (and perhaps only) economical source of fuel, shielding and construction material.