Stanley G. Weinbaum is best known for the 1934 short story “A Martian Odyssey,” lionized by readers and critics alike after it appeared in the July issue of Wonder Stories. Isaac Asimov would later opine that “A Martian Odyssey” was one of a handful of stories that changed the way all later science fiction was written. But Weinbaum’s depiction of a genuinely alien being called Tweel sometimes obscures his other work, which you can find collected in The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum (1974), a worthwhile addition to the library of any SF fan, and a reminder of the loss the genre suffered when the author died at age 33.

This morning I’ve been thinking back to a little known Weinbaum story called “Redemption Cairn,” which ran in the March, 1936 Astounding Stories and which, because I have a good run of Astounding issues from that era, sits not ten feet away from me on my shelf. I don’t know if this is the first appearance of Europa in science fiction, but “Redemption Cairn,” with its exotic biosphere in a valley on the moon, shows us a time when Jupiter was thought to produce enough heat to make the Galilean moons habitable. Arthur C. Clarke would imagine a warm Europa as well, but his, in 2061 Odyssey Three (1988) was the result of Jupiter’s transformation into a small star and the birth of a biosphere.

One thing we’re not going to find when we get a dedicated probe to Europa is a tropical habitat, but the musings of science fiction writers remind us that we shape our aspirations around our dreams, and the encounter with the unknown becomes just as meaningful in real life whether the ocean we’re probing lies under balmy skies or a kilometers-thick layer of ice. Want to see an icy, science fictional Europa? Try Kim Stanley Robinson’s Galileo’s Dream, in which the astronomer is transported from Padua into the depths of Europa’s deep ocean.

Image: Science fiction pioneer Stanley G. Weinbaum.

A NASA Request for Information

Galileo had plenty of Europan connections, from being the person who discovered the moon to having his name attached to the spacecraft that sent us our best images of the surface. Like all of us, NASA would like more information about Europa than the Galileo mission could provide, and while it takes science fiction to get us into the Europan ocean for now, down the road we may have more concrete options. The agency’s recent issuance of a Request for Information (RFI) asks the scientific and engineering communities to come up with ideas that can help us answer some of our longest-standing questions. The ultimate goal: A $1 billion mission (excluding launch) that can achieve the following goals, or at least as many of them as possible:

- Characterize the extent of the ocean and its relation to the deeper interior

- Characterize the ice shell and any subsurface water, including their heterogeneity, and the nature of surface-ice-ocean exchange

- Determine global surface, compositions and chemistry, especially as related to habitability

- Understand the formation of surface features, including sites of recent or current activity, identify and characterize candidate sites for future detailed exploration

- Understand Europa’s space environment and interaction with the magnetosphere.

These requirements come from the National Research Council’s 2011 Planetary Science Decadal Survey. Why we need a mission like this is clear enough. For all its achievements, Voyager could give us nothing more than a quick flyby, and while the Galileo spacecraft was able to make repeated flybys (fewer than a dozen), it labored under serious communications problems with the failure of its high-gain antenna. We’ve seen what Cassini can do in the Saturn system with repeated observations of high-value targets like Titan and Enceladus, but Europa is a tough nut to crack, particularly given the radiation environment that surrounds Jupiter.

For more on the RFI, whose deadline is May 30, visit the NSPIRES site. NASA has been funding work into mission concepts and in particular the science instruments that will be needed for Europa, including possible ways to penetrate surface ice. The Decadal Survey considers a Europa mission among the highest priority scientific pursuits for the agency, and the recent findings from Hubble of possible water vapor ejections from the moon’s surface add punch to the statement. The RFI, says John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for the NASA Science Mission Directorate at the agency’s headquarters, “is an opportunity to hear from those creative teams that have ideas on how we can achieve the most science at minimum cost.”

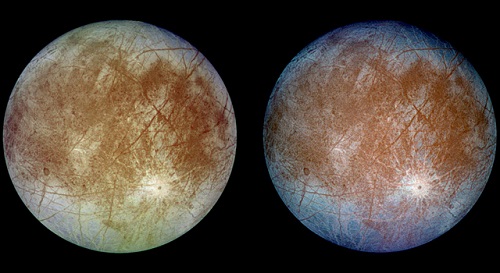

Image: Two views of the trailing hemisphere of Jupiter’s ice-covered satellite, Europa, returned by the Galileo spacecraft. The left image shows the approximate natural color appearance of Europa. The image on the right is a false-color composite version combining violet, green and infrared images to enhance color differences in the predominantly water-ice crust of Europa. Dark brown areas represent rocky material derived from the interior, implanted by impact, or from a combination of interior and exterior sources. Bright plains in the polar areas (top and bottom) are shown in tones of blue to distinguish possibly coarse-grained ice (dark blue) from fine-grained ice (light blue). Long, dark lines are fractures in the crust, some of which are more than 3,000 kilometers (1,850 miles) long. The bright feature containing a central dark spot in the lower third of the image is a young impact crater some 50 kilometers (31 miles) in diameter. This crater has been provisionally named “Pwyll” for the Celtic god of the underworld. Credit: NASA/JPL.

Through Galileo’s Lens

But back to science fiction, and Kim Stanley Robinson, a fine science fiction author indeed. In Galileo’s Dream, before the celestial voyaging that will give Galileo a much closer look at what he sees in his telescope, Robinson depicts the discovery of the Galilean moons:

On the night of January 12, Galileo trained the glass on Jupiter in the last moments of twilight. At first he could see again only two of the little bright stars, but an hour later, when it was fully dark, he checked again, and one more had become visible, very close to Jupiter’s eastern side.

He drew arrows trying to clarify to himself how they were moving, shifting his attention between the view through the glass and his sketches on the page. Suddenly it became clear, there in the reiterated sketches: the four stars were moving around Jupiter, orbiting it in the same way the moon orbited the Earth. He was seeing circular orbits edge-on; they lay nearly in a single plane, which was also very close to the plane of the ecliptic, in which the planets themselves moved.

He straightened up, blinking away the tears in his eyes that always came from looking too long, and that this time came also from the sudden urge of an emotion he couldn’t give a name to, a kind of joy that was also shot with fear. “Ah,” he said. A touch of the sacred, right on the back of his neck: God had tapped him. He was ringing.

Image: Portrait of Galileo by Ottavio Leoni (1578-1630).

The pace of space exploration is sometimes frustrating, particularly when we gauge it against the optimism of the Apollo era and the dreams of von Braun. But when I think about Europa and our opportunities there, I always think back to this passage in Robinson, and ultimately back to Galileo himself. We have come so far since the days when he identified those bright objects around Jupiter as moons. Surely the drive for discovery — the zest, the enchantment of it — that drove Galileo is something hard-wired into our species, a sort of ‘ringing,’ as Robinson describes it, or perhaps a kind of inner fire that won’t allow us to turn away from these explorations.

Just before I read this post I was reflecting on how some future predictions massively under delivered… whether it be human colonisation of space, flying cars or nuclear fusion. Meanwhile, the real revolutions occurred in areas that weren’t well pre-advertised in mainstream culture, whether it be computers and the internet or the abundance of exoplanets and their detection techniques. While we are way down on where we hoped to be with missions to the outer gas giants, seems that we are up on discoveries of exoplanets which are coming through all the time

Not to say that I think we should be content with our generally underwhelming rate of solar system exploration. Much more should be being done, and I think we need a comprehensive look at how our species views itself and it’s place in space. Most people seem to have no consciousness of being on a planet within in a solar system at all, to many the moon is no more real than the 2D projection stuck on the ceiling of a planetarium, but new technology can bring many opportunities to change people’s experience of space around us as well as opportunities for education.

Somebody with some motivation and programming skill needs to make an app for Google Glass that gives us a view of exactly where all the solar system bodies are around us and their orbits, show us where the extra-solar planets are in the sky, and give us X-ray vision to see through the Earth to all the other countries and oceans, seeing our planet holistically for the first time.

Online learning MOOCs, such as those on Coursera, are a great opportunity for reaching dynamic and driven young people with a first for knowledge. Perhaps the Centauri Dreams / Tau Zero community could come together to build an Interstellar Travel MOOC?

Astrobiology Magazine

Ship of Dreams

05/01/2014

Author: Sheyna E. Gifford, MD

Summary: The first mission to Europa in more than a generation has been designed.

It all began on a clear night in 1610 AD. Galileo Galilei caught glimpses of four bodies that would later bear his name — the Galilean Moons. Because Jupiter’s largest satellites were so bright, Galileo called them, “stars.”

Over the centuries, Europa, the most luminous of all the Galilean moons, has provided an abundance of mysteries. These culminated in what may have been a literal explosion in December 2012, when a cloud of water vapor was seen 20 miles over its south pole. This eruption was tiny on the cosmic scale, but enormous in its importance to astrobiology.

Outside of Earth, Europa may be the most hospitable home for life inside the Solar System. Four billion years of tidal heating and a liquid ocean may have given rise to something we can identify as life. A man-made satellite in the Jovian system could potentially capture traces of that life in the water vapor shooting from Europa’s surface. Yet, in spite of the exciting science, a dedicated mission to Jupiter hasn’t launched in a generation.

That could all change if the Europa Clipper were built.

Full article here:

http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/6155/ship-of-dreams

@Lionel

http://www.theplanetstoday.com/

I also use this free software to locate stars/planets as well

http://www.stellarium.org/

Now that reminds me to get my 8″ mirror recoated.

I believe you’ll find that Weinbaum’s character should be “Tweerl”.

And is there any way to get folks affiliated with the US Gov’t to use the good old word “decennial” rather than the ugly & incorrect “decadal”? The Census Bureau doesn’t have that problem!

The problem with Europa is radiation. Jupiter’s. Europa is deeply imbedded in its radiation belts and it was this reason that NASA cancelled its plans for an Orbiter. The substantial extra weight required to protect the satellite and its instruments needed unrealistic volumes of propellant to get it to Europa , which involves a complex series of spiralling in flybys . The JUICE ESA mission planners did their best to pick up the slack by including 2 Europa flybys in their Ganymede Orbiter ( via Callisto) plans but any more even than that was prohibitively expensive due to the radiation protection/extra fuel dichotomy. Although a flyby only mission mitigates some of the radiation exposure compared to an orbiter. Galileo was battered by the end if its mission , but it did last nearly 15 years. ESA estimated that to achieve the same objectives as an Orbiter , a flyby mission would require 50-100 such flybys.

NASA is tentatively exploring plans for such a mission ironically ( in the event of funds becoming available), Europa Clipper, with multiple flybys as close as just 25 kms, but even that has been provisionally costed at $2 billion.

With the deteriorating Russian situation they will also be obliged to push on aggressively with the SLS too, which whilst probably good long term especially in terms of interplanetary transfer times , is going to take up a substantial chunk of the NASA budget for a good few years .

publius writes:

Nope. He’s called ‘Tweel’ throughout the story, although there is this bit at the beginning that explains the additional ‘r’:

But Weinbaum uses ‘Tweel’ from then on. Great tale.

I see little point in making landfall on Europa without a BFD (the last word is drill).

Weinbaum’s story is online here:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/23731

There’s a sequel story, “Valley of Dreams”, which is not nearly as good. Weinbaum was a fine writer overall, but uneven.

A bit of trivia: Weinbaum’s widow outlived him by almost sixty years. When she passed away in the 1990s, she left his papers to his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin. They discovered a couple of unpublished, never-before-seen short stories! AFAIK, they’re still unpublished — I believe the last Weinbaum anthology was in the 1980s.

Doug M.

As to Europa, what Ashley said. The radiation environment poses major challenges and dramatically increases the expense of any mission there. We’re not going to get a major Europa misison (multiple flybys, never mind an orbiter or a lander) for less than a couple of billion, and at that point we’re into flagship mission territory.

ESA’s JUICE — currently scheduled for a 2022 launch with Jupiter system arrival in late 2030 — would do two Europa flybys in the early 2030s before settling down into orbit around Ganymede. At this point that looks like all the Europa we’re going to get within the next 20 years. I’d be happy to be wrong, but given the lead times — in round numbers, 8-10 years to get a mission launched, and another 7-8 to get it to Jupiter — right now it seems very unlikely that anything else will arrive at Europa before the back half of the 2030s.

Doug M.

While it’s a damn shame that JUICE won’t do much with Europa, it will probe the hell out of Ganymede and poor, neglected, much-maligned Callisto. Just a few highlights:

— it’ll photograph all of Ganymede and most of Callisto at <400 m/pixel, with selected local targets down to 5m/pixel or less

— it'll scan the surfaces of the moons with three different spectrometers, giving a detailed chemical composition plus important clues about internal processes

— it'll use a laser altimeter to give 3-D mapping and details on tidal movements

— it'll have a radar instrument that should be able to probe the structure of the icy crusts down to several km depth

— a magnetometer and a gravimeter, which will combine to give all sorts of details on the moons' internal structure

— and a bunch of other stuff looking at particles, plasma, and VLB interferometry.

If it comes off, JUICE will be an awesome pure-science mission. Even if it won't do much with Europa, it will tell us a tremendous amount about those moons. So, fingers crossed that it goes off without a hitch, and that we're still around in the 2030s to see what it has to tell us.

Doug M.

Andrew, we may not need a big, um, drill at Europa if we can sample the water vapor being emitted from Europa’s southern regions into space. And if the dark material in the many cracks across the moon’s icy surface are what I think they might be, then we just need to land, scoop, and analyze.

Some kind of drill may come in handy if we still want to send a submersible into the Europan ocean, which would be incredible of course. I just do not see NASA or anyone else ponying up the serious cash for such a mission yet.

Crazy thought I have not researched enough idea time: Would radiation exert enough pressure to move a probe around? Could the shielding designed to protect the probe also be used as a kind of sail?

I am just saying if you are going to need lot of shielding to protect a vessel in the vicinity of Jupiter, you might also well put it to good use in addition to keeping the probe from being fried. If lots of shielding is considered a stumbling block to Europa exploration, that is.

@Michael

Thanks for those, played with them both and Stellarium is now installed on my Mac

An Augmented Reality version, however, would be really cool – wonder whether anyone anywhere has started working on this for Glass

The Europa Clipper costed out at $2 billion. That’s not so far away from what NASA are proposing for their budget. That’s also a very stingey costing so it may be they will go a little further without committing to “flagship” territory as mentioned above . Even an L1 ESA mission like JUICE comes in at about €1 billion with a free launch thrown in. The key is protecting the instrument package with as little weight as possible as its that which adds the need for extra propellant and thus cost. I’m sure the proposals they receive will be for a multiple flyby concept rather than an orbiter, which helps reduce time in the radiation belt a bit ( although even then, if you look at the JUICE mission , 25% of total overall radiation exposure for the entire 3 year mission is from the two Europa flybys which take up just over a month!) . Its a question of whether anyone can come up with a novel radiation protection method that doesn’t take up much mass, which would ironically sit well with manned missions to Mars. Ionising radiation for instance is quite well shielded by hydrogen containing materials although particle radiation less so.

@ljk May 2, 2014 at 10:14

‘Crazy thought I have not researched enough idea time: Would radiation exert enough pressure to move a probe around? Could the shielding designed to protect the probe also be used as a kind of sail?’

Some of the radiation is moving very fast 0.1 – 0.2c and would most like penetrate quite deep into the shielding rather than be reflected. But uncoiling a wire loop and running a current through it would produce a fair force and deflect charge particles effectively, the current and direction of the loop and field can be adjusted as well. They just need to place more shielding at the polar regions of the dipole possibly saving weight. This dipole would also interact with Jupiter’s main field and could be used to orientate the craft.

@Lionel May 2, 2014 at 10:36

‘An Augmented Reality version, however, would be really cool – wonder whether anyone anywhere has started working on this for Glass’

You could drop them an e-mail, they may not respond but somewhere in time they may pick the idea up or someone out there will.

This is rather frustrating. We know what to do and how to do it, but we don’t have the means to pay for it. There exist people who could pay for it, but don’t have the vision to want to. This is rather frustrating.

In case this is useful to anyone, it appears that the relative radiation of Jupiter’s outer satellites are:

Ganymede: 100th of Europa’s radiation flux

Callisto: 1,500th of Europa’s radiation flux

sorry to repost, I think it’s clearer to write it this way:

In case this is useful to anyone, it appears that the relative radiation fluxes suffered by Jupiter’s outer satellites are:

Ganymede: 1/100 th of Europa’s radiation flux

Callisto: 1/1500 th of Europa’s radiation flux

Radiation around Europa, not for the faith hearted! This is most probably the biggest reason to go for Ganymede as opposed to Europa.

http://people.virginia.edu/~rej/papers09/Paranicas4003.pdf

More info as discussed on this site

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=29680

Not so old Europa mission concept

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/opag/mar2012/presentations/Europa_Reports/1_Europa_Mission_Studies.pdf

“Galileo” made a dozen or so Europa flybys and although it took a beating it lasted 15 years. The extensive mission delays it underwent meant it was utilising 1980’s hardware too. I see one of the proposals made in relation to Galilean moon missions is to utilise Jupiter’s own substantial radio output as a supplement to the ice penetrating radar using the same antenna and little more energy . That’s the sort of ingenuity needed to come up with the novel form of radiation shielding required for more extensive Europa flybys for me. I reckon it comes down to mass though. The less required for “getting you there” propellant, the more available for shielding, That space sail sounds increasingly interesting.

A modest proposal for a Europa probe: would it not be easier to

land craft and have it burrow itself in a snow shelter, leaving only

it’s sensor suite exposed (hopefully it can deploy back-ups suites as needed) and the keep main probe systems protected ?

Isn’t this easier than trying to protect a Europa orbiter from radiation?

Galileo was a flagship mission; it cost about $1.4 billion (NASA’s estimate) in 1990s dollars, so say about $2 billion today. It looks very unlikely that NASA will be able to make that kind of commitment any time before the end of this decade.

As to ingenuity and space sails, NASA is currently headed in the exact opposite direction. The present trend is more and more towards tested, robust, tried-and-true “heritage” technologies. This is why, for instance, we’re going to launch a Mars Rover in 2020 that will be very close to an identical copy of MSL — right down to using the RAD750 chip, which was developed in 2001 and first deployed in 2005. It won’t be very innovative, but we know it works.

So it’s very unlikely that NASA will deploy a dramatically new propulsion technology any time in the near future. And if they do, they’ll try it out on small and cheap stuff multiple times before daring to use it on a major mission. That was the pattern with the last major innovation: ion drives were used for 20 years on satellites for station keeping and in multiple Soviet spacecraft before NASA agreed to try an ion drive on Deep Space 1, in 1998. And Deep Space 1 was a cheap little mission ($150 million in late 1990s dollars) that was very deliberately designed as a testbed for new technologies.

Not to be all buzzkill-y, but we’re currently in the middle of a period of relative stagnation in spacecraft design. Propulsion, avionics, materials, energy sources, shielding, communication systems — all have been fairly stable for over a decade, with most changes being incremental and modest. I don’t expect this period to last forever, but I won’t be surprised if it continues for another decade or more — either until there’s a currently unexpected technological or engineering breakthrough, or until someone decides to throw some money around and take a flyer on some new ideas.

To bring it back to Europa, that means that novel concepts for propulsion and shielding are very, very unlikely to be incorporated into the next Europa mission. Kind of a bummer, but there it is.

Doug M.

Another plea to explore Europa – yes it is preaching to choir here, so spread the word if you truly care:

http://aeon.co/magazine/nature-and-cosmos/its-time-to-look-for-life-in-europas-ocean/