In our email conversations leading up to my publishing Human Universals and Cultural Evolution on Interstellar Voyages, Cameron Smith confirmed that there were few anthropologists engaged in studying long-term spaceflight. The same can be said for historians and sociologists, although we do have some prominent names devoting themselves to changing that. Kathleen Toerpe is doing splendid work with the Astrosociology Research Institute (I’m hoping for a new report from her soon in these pages), while Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience (1985) made a determinedly multidisciplinary effort to study our place in the cosmos.

The latter book was actually the proceedings of the Conference on Interstellar Migration held in Los Alamos in 1983, and it remains a storehouse of insights into spaceflight’s effect on humanity. Presenters at the 100 Year Starship symposia have thus far been multidisciplinary as well, with representation from biologists, philosophers, writers and psychologists as well as scientists working the ‘hard science’ fields of propulsion and aerospace engineering. Of course, the place where starflight is most vividly presented from all angles of human experience is in science fiction, which over the years has explored many of the issues raised by, for example, putting a human crew into a multi-generational starship and shooting for Alpha Centauri.

Reading Cameron Smith’s essay, though, had me thinking all weekend about some of the fictional situations great writers have gotten their interstellar crews into. A trip that takes a thousand years inspires thoughts of generations that eventually forget their mission and may not realize they are on a starship. This is familiar turf, worked by Brian Aldiss in his novel Non-Stop (1958), and of course famously portrayed by Robert Heinlein in Orphans of the Sky, which grew out of two novellas in Astounding Science Fiction. Ever the bibliographer, I must mention both: “Universe,” in ASF May, 1941, and the sequel “Common Sense,” which ran in October of the same year.

But if crews that forget where they are is a classic trope of science fiction, somewhat less so is the different kind of ignorance portrayed by J. G. Ballard’s crew in “Thirteen to Centaurus,” a story mentioned by Centauri Dreams commenter Alex Tolley over the weekend. Here the issue is how human crews react to long-haul spaceflight, and we learn early on in the story that the narrative being told by the authoritative ship’s doctor is not exactly what it seems. Here he’s speaking with a young man who has come to believe that his ‘world’ may be a ship:

“You’d more or less guessed before I told you. Unconsciously, you’ve known all about it for several years. A few minutes from now I’m going to remove some of the conditioning blocks, and when you wake up in a couple of hours you’ll understand everything. You’ll know then that in fact the Station is a spaceship, flying from our home planet, Earth, where our grandfathers were born, to another planet millions of miles away, in a distant orbiting system. Our grandfathers always lived on Earth, and we are the first people ever to undertake such a journey. You can be proud that you’re here. Your grandfather, who volunteered to come, was a great man, and we’ve got to do everything to make sure that the Station keeps running.”

Abel nodded quickly. “When do we get there — the planet we’re flying to?”

Dr. Francis looked down at his hands, his face growing somber. “We’ll never get there, Abel. The journey takes too long. This is a multi-generation space vehicle, only our children will land and they’ll be old by the time they do. But don’t worry, you’ll go on thinking of the Station as your only home, and that’s deliberate, so that you and your children will be happy here.”

This all seems familiar for a time, but of course this is J. G. Ballard, in whose hands the tools of science fiction take evocative new form. Normally I would worry about spoiler alerts, but this is a short piece and the reader learns early on that things are not what they seem, so I feel comfortable saying that Dr. Francis is himself lying, that the ship is a long-term Earthbound experiment, and that its crew is being used to study the problems humans will have when we really do send ships to another star. The boy Abel is smart enough to start seeing through even this subterfuge, and our friend Dr. Francis learns he has an agonizing decision to make.

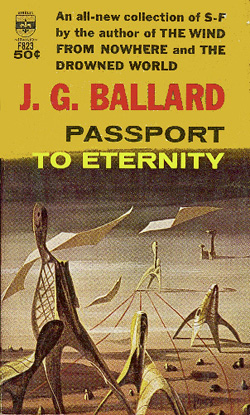

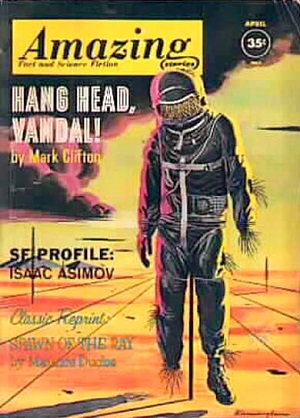

Published in the April, 1962 issue of Amazing Stories — then under the leadership of Cele Goldsmith, whom I consider one of science fiction’s great editors — “Thirteen to Centaurus” was also dramatized by the BBC in 1965 as part of its ‘Out of the Unknown’ series. If you’re not a collector of old magazines, you can track it down in 1963’s collection Passport to Eternity, or more easily still in 2010’s The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard.

It would be interesting to know how much of an influence the Ballard tale played on Bruce Sterling, whose story “Taklamakan” won a 1999 Hugo Award. Here simulation again comes into play, this time in a remote cave under the Taklamakan desert. There, within three enormous structures each the size of a high-rise building, what one of the characters calls ‘a dry-run starship experiment’ is ongoing, an entire, isolated community having been chosen for the task, which has aspects of both ethnic cleansing and scientific study. The characters ‘Spider Pete’ and Katrinko talk over the ramifications:

“You suppose these guys really believe they’re inside a real starship?”

“I guess that depends on how much they learned from the guys who broke out of here with the picks and the ropes.”

Katrinko thought about it. “You know what’s truly pathetic? The shabby illusion of all this. Some spook mandarin’s crazy notion that ethnic separatists could be squeezed down tight, and spat out like watermelon seeds into interstellar space. . . . Man, what a come-on, what an enticement, what an empty promise!”

“I could sell that idea,” Pete said thoughtfully. “You know how far away the stars really are, kid? About four hundred years away, that’s how far. You seriously want to get human beings to travel to another star, you gotta put human beings inside of a sealed can for four hundred solid years. But what are people supposed to do in there, all that time? The only thing they can do is quietly run a farm. Because that’s what a starship is. It’s a desert oasis.”

And maybe you’ll remember one last story that traded off isolation and experimentation on human crews. The very first episode of Rod Serling’s series The Twilight Zone was “Where Is Everybody?” First broadcast in October of 1959, the story, written by Serling, stars Earl Holliman as a man who finds himself in a town where no one seems to exist, even though evidence of recent occupation is everywhere. We learn at the end that the character Holliman plays, Mike Ferris, is an astronaut in training. He’s been inside an isolation room for almost 500 hours during a simulated trip to the moon. Can the human mind handle deep space in tiny spacecraft?

The message of the show is ‘yes,’ as Ferris looks out and sees the Moon when he is being taken on a stretcher to the hospital. His hallucinations haven’t altered his determination. He yells into the sky:

“Hey! Don’t go away up there! Next time it won’t be a dream or a nightmare. Next time it’ll be for real. So don’t go away. We’ll be up there in a little while.”

I wonder if just not being able to go anywhere would be enough to keep the “middle crew” aboard a generation ship (the one that will never know either the Earth or the destination) behaving well. It’s not like they could turn the starship around and head back, and even if they could they might not make it back to Earth in their life-time. That might drive a kind of fatalism about the whole situation that keeps them focused on keeping the mission going.

There are very strong psychological barriers to changing one’s situation, rather than just adapting to it. However hard the peasant’s life, suicide is rarely attempted to get to the desirable afterlife. Prisoners, even knowing the world outside their bars, do not often attempt jailbreaks. People will live in extraordinarily constrained conditions, and will not move. In my neck of the woods, I’m amazed at the number of Californians that do not have passports, and haven’t even left the state. The ties of home and family can be very strong.

My guess is that the starborn will be the most adapted to their life, having not known any other. Their parents who started the journey will be the least adapted. The problem might be that non of the crew/passengers will want to leave the ship at its destination for fear of the unknown.

However, like Alvin in Clarke’s “The City and the Stars”, it is the minority who have wanderlust that will be the problem on a starship, who will feel constrained by the prison they are in.

On long trips, it wouldn’t surprise me if stability was reinforced by the evolution of rituals and even religion.

Diaspar was a civilization bottled up inside a hollow mountain…

The balm of true love is seldom on display in science fiction…

It’s usually about some kind of suicide…or insanity…

Remembering Dreadful Sanctuary…

To awful even to become a movie…

Brett, right. I think current humans aren’t quite cut out to endure in this environment. The poor “middle generations,” as you have labeled them, might harbor a great deal of resentment. Since the chain is only as strong as the weakest link, the likelihood of extreme failure seems very high to me, even if all the remaining technical and non-psychological problems have been solved.

I think breakthrough propulsion combined with sleeper-ship or seed-ship technology is far more promising.

At some point the upward curve of human life expectancy will meet the downward curve of travel time. That’s when I think interstellar travel first happens. Multi-generational ships may still become a reality, but I think it will be after we have mastered space colonization. At that point it will largely be about the logistics of moving an existing colony model from point A to point B. I think these people will have long forgotten and/or lost any interest in planetside living and will have learned to make themselves comfortable. In fact, I expect it will be people purposely seeking isolation much like the Puritans did.

Unless alternatives to generation ships (hibernation, faster propulsion) come about, before an interstellar voyage is possible there will be free-floating colonies in the asteroids, the outer planets’ moon systems, the Kuiper belt and maybe eventually the Oort cloud. The social dynamics of being in close-knit communities will have been worked out, and there will be experience with colonies being separated by greater and greater travel and communications times.

Even today, people live on quite small islands with limited outside contact. e.g. Bermuda (area= 52 km^2 ), Easter Island (area = 163 km^2), well below the size of the O’Neill Island 3 ( ~ 450 km^2). Although neither of these places could support more than a pre-C19th standard of living without outside contact. As Craig says above, inhabitants will have adapted and starflight may be very little different from living in the outer reaches of the solar system. The major difference being loss of most contact.

Bermuda is perhaps the closest place I have ever been that mimics living in an isolated O’Neill colony. In the middle of nowhere, almost idyllic (but could do with lower humidity). Earns its living from tourism and asset management. A space colony could do much the same, unless it really wanted to build powersats :)

You missed the Canadian series “Starlost.” The generation ship had been damaged by a large rock and the crew that ran it was killed. A small group of farmers discovered the truth , and for two years (or so) tried to get the ship back on course.

As we expand into space, we’re going to colonize further and further from Earth, with longer and longer trip times. Some of these colonies will be deliberately out of contact with the rest of humanity, as experiments in social or biological evolution.

By the time we’re colonizing distant Kuiper belt objects, a generation ship will just be a typical outer belt colony in motion. A colonized proto-comet with a big honking engine.

Are humans up to this, psychologically? Of course we are, most of our evolutionary history consisted of small groups where you lived in the same place, with no distant communications. It’s only very recently that people have been able to visit places beyond walking distance, or communicate with folks on the other side of the world. It’s not going to cause madness to stick people in circumstances materially better than we evolved under!

A world ship would be less cut off from the rest of mankind than an Amazon tribe. Physical visits might be unfeasible, but communications would be no worse than at the time North America was first colonized from Europe. Even when the world-ships get lightyears from Earth, they’re likely to be within light-months of other world ships. Technological progress will reach the colonies, art and literature.

It might even be feasible to upload and transmit home the people who can’t hack it. Partway through the voyage, the world-ship might become a sleeper ship, or medical advances passed on, (Or originated locally!) extend the human lifespan to the point where the first generation does make the trip.

The bottom line, though, is that a world-ship isn’t that huge a change from what humanity has coped with in the past.

One reason SF is popular with teenage boys is because youth has the necessary ignorance to suspend their disbelief. Once you get older though you start to realize all the engineering problems with these stories of simulated starships that never leave the earth. For example, none of the crew ever wonders why there is never the slightest various in acceleration or gravity? No one ever questions how the environmental systems can function so perfectly as to provide fresh breathable air for years on end? There is never the need for a spacewalk to inspect the ship, fix something, or just provide some variety, etc, etc. In the real world the International Space Station requires constant maintenance and the inhabitants often wear ear plugs to shut out the constant hum from all the electr0nics. As I approach retirement age, SF stories now make me recall Hemmingway’s final line in The Sun Also Rises: “Isn’t it pretty to think so.”

Did all the SF ‘World Ships’ always have a destination?

I can’t remember.

Because in James Blish‘s epic Cities in Flight there were destinations but those places were never colonized. Whole cities , New York, for instance is ripped out of the ground and sent to the stars on the wings of Spindizzies – FTL, ‘anti-agathics’, ultraphones, the instantaneous DIRAC … not really generation to generation ships but my o’ my Jim Blish trumped all ‘world ships’ forever. In interstellar flight I know of nothing like it.

It even has an up-beat end-of-the -universe ending!

What can one say!

I cannot believe that any one now living would,voluntarily board a multi generation spaceship knowing that they were going to spend the rest of their life on board it—knowing too that they would never see familiar places or faces again– that they would never reach the ships intended destination– that in fact they would live their allotted span in the awareness that they would never leave the ship again while they lived . And this in my view will not alter without there being no alternative , such as the need to leave Earth due to the likelihood of its imminent destruction of its ability to support life.

Some would perhaps be willing to board a spaceship if the voyage to a distant destination could be accomplished within a reasonable fraction of a normal life span , or that they would be unaware of the passage of time during the voyage ,no matter how long it took .There would also be a need for there to be an assurance of some kind that they were not headed for a totally hostile destination.

To me therefore it seems unlikely that humans in their present form will ever embark on colonising voyages to destinations in deep space .Our physical condition and mental health are such that it is questionable whether we will even be able to support Space travel within the solar system But hopefully this may be overcome by medical science, individual selection and actual experience. Who knows ?

Of course matter transportation a la ‘Star Trek’ might ultimately be feasible but who or what goes first ?Presumably some pioneering AI based package to test the water so to speak.. Although we had so far found no evidence of life ,much less intelligent life , elsewhere in the Universe , many still believe that it exists, and that we shall ultimately encounter it Maybe! But neither have we found any evidence of Inter- Space communication between Star systems either in Material form or in the form of IT. I consider it possible that advanced intelligent life may exist in a non material form In combinations of massless eletrically charged particles that constitute all matter less the Hobbs component. ‘ With Wild surmise upon a peak in Darien’NW

Al Jackson writes:

Now you’re talking, Al! And my copy of Cities in Flight is right across the room on the shelf. What great stuff…

Wait a minute here! Yes, New York New York kept stumbling over worlds which no one knew were inhabited, but the underlying economic reality was that NY NY wasn’t self-sufficient, and that the city “worked for a living” by selling its services to clients — typically planets — with lesser technological skills. Thus the slogan of the city, a vagrant’s “Mow your yard, lady?”

And while we’re on these topics, Cities In Flight, and long interstellar journeys, we might want to recall something mentioned but not dwelt upon by Blish — that his City’s journeys were often more than a normal human lifespan, that a handful of the population was valuable enough to have their life extended by anti-aging drugs and thus might live for millennia, but most of the people were only “passengers”, who aged normally and might never know any existence but that of the city-ship.

Personally, I doubt that long duration interstellar spaceflight is going to be practical until we’ve got suspended animation down pat (or some reasonable equivalent, like brain uploading and downloading into ersatz human bodies, but maybe that’s my prejudice showing. Hopefully, when we get the starships we’ll have also gotten to successful long sleep.

Let me ask this instead: I’d guess that laser-based communication is possible between earth and spacecraft for distances out to a couple of light years (2 LY perhaps for a spacecraft with an adequate power source , or maybe 10 LY for a spacecraft receiving a signal from the solar system). I’ll leave open the idea of whether a generation starship would reach that 2 LY distance in 2 years or 2000. The question is whether sufficiently “dense” communications would be an adequate substitute for “real” human interactions.

I.e., if we’re on a multi-generation starship, can we more or less overlook that we’re basically voluntary convicts in a traveling prison if we still have the internet, multiplayer games, Netflix, downloads of the Booker Prize nominees, etc?

Could the children of colonists in New England overlook it? It may be the perenial cry of the teen: “I didn’t ask to be born!”, but virtually every human generation has survived, being stuck where their parents landed them. Long distance travel and communications are a novelty, not the normal state of mankind.

I cannot believe that any one now living would,voluntarily board a multi generation spaceship knowing that they were going to spend the rest of their life on board it—knowing too that they would never see familiar places or faces again– that they would never reach the ships intended destination– that in fact they would live their allotted span in the awareness that they would never leave the ship again while they lived .

Surely that depends on the size of the worldship and the conditions you grew up in. If you grew up in a space colony, turning it into a star ship might not make much of a social change at all.

We just happen to be adjusted to life on a worldship with 7 billion people. We don’t miss those other people in the galaxy we are cut off from. We have been “prisoners” on our ship for a very long time, in fact we evolved our species here. We have developed some very pathological socio-economic systems to live within. Failing to maintain population control, we have stripped our resources unsustainably and might be running into real trouble. I really want to leave and reconnect with civilization, but I cannot. :)

@mike shupp

‘Personally, I doubt that long duration interstellar spaceflight is going to be practical until we’ve got suspended animation down pat (or some reasonable equivalent, like brain uploading and downloading into ersatz human bodies, but maybe that’s my prejudice showing. Hopefully, when we get the starships we’ll have also gotten to successful long sleep.’

But what if you could live and die and be reborn, i.e. the same baby with same genes, version 2 or Bob 2. You could have memories of your previous lives recorded digitally, if you have a bad gene maybe it could be removed or at least you know before hand when things go bad so medication could help in time. So on a 5 thousand year journey you will be born 50-100 times or you could chose to be born at later dates.

‘Let me ask this instead: I’d guess that laser-based communication is possible between earth and spacecraft for distances out to a couple of light years (2 LY perhaps for a spacecraft with an adequate power source , or maybe 10 LY for a spacecraft receiving a signal from the solar system).’

Instead of using light to communicate could we accelerate a sail with a complete download of everything that happened in 5 years attached to it to catch up with the craft.

Brett, Alex, Michael — The underlying issue is whether on a flight lasting generations it is possible to maintain psychologically fit crew who will ultimately construct colonies with sane, and perhaps even admirable, human societies. We would like our far-flung descendants to live as persons we could respect, rather than as mindless slugs or genocidal fanatics, let us say. We would like them to play games, to fall in love and marry, to listen to Beethoven and the Beatles or equivalents, to read novels, to debate politics, to ponder the heavens and ask deep philosophical thoughts, and so on.

So we need to consider the mental health and stability of the crew, particularly of the first generation crew members who may find themselves progressively isolated from what we would regard as normal human society. Thus my question, of whether communication between the crew and the society they left behind can substitute for this loss.

The light speed limit imposed on all forms of communication is already a significant handicap to voice communication over long distances . [Such as on a manned voyage to Mars ] or to the remote control of robot vehicles on its surfac. and as distances increase it will rapidly become practically impossible, And of course this limitation applies to all forms of communication . We may be able to work around it while exploring the solar system but to attempt real Space travel under this handicap will be well-nigh impossible, especially since it is likely that we will never be able to accelerate spaceships to more than 10% of light speed .

While at present it seems impossible to exceed this limit,never the less it is odd that in a Universe that is virtually boundless the speed of communication should have a finite limit. Being a believer in the view that necessity is the mother of invention,I therefore think that maybe some day a way of overcoming this limitation will be discovered .Only then will we truly be able to accomplish real voyages through Space and Time

@Mike Shupp – doesn’t the size of the crew/passengers matter here? People on Earth quite happily live in towns, (even small villages) without incurring mental health problems due to isolation. A century ago, they didn’t have much outside stimulation either – books, newspapers, letters from relatives, etc. In my early life, telephone and broadcast tv was added to the mix. I could therefore see that the crew might well live comfortably, receiving only aging data streams from society and relying on social interactions on board to maintain stability. That may be a wrench for our crew of several centuries hence, but it should be adaptable, as we can adapt to C19th communication levels too.

@Norman – I do not see “instant” communication as a requirement for stellar travel. As I noted above, humans lived without this until just the last century, and we can live without it again – some people even seek it out.

I don’t expect the crew to be a bunch of extroverts, getting depressed at the lack of external social interaction. Maybe the crews need to be selected for introversion?

Mike: I understood the question, I just doubt that conditions in relevant ways similar to most of our evolutionary history are going to challenge human sanity.

“Maybe the crews need to be selected for introversion?”

The universe will be conquered by people with Asperger’s. That’s just one of the ways those who conquer space will differ from the average member of Homo Sap.

Brett Bellmore said on June 5, 2014 at 17:18:

“Maybe the crews need to be selected for introversion?”

“The universe will be conquered by people with Asperger’s. That’s just one of the ways those who conquer space will differ from the average member of Homo Sap.”

Do we really want to release entire fleets of Sheldon Coopers (from The Big Bang Theory television series) onto an unsuspecting galaxy?

This should also make one wonder what kind of ETI has succeeded into exploring the Milky Way….

Brett Bellmore said on June 4, 2014 at 10:10:

“Could the children of colonists in New England overlook it? It may be the perenial cry of the teen: “I didn’t ask to be born!”, but virtually every human generation has survived, being stuck where their parents landed them. Long distance travel and communications are a novelty, not the normal state of mankind.”

So what you are saying in so many words is “Suck it up and deal with it.” Hey why not, none of us are going to be stuck in a big tin can for generations wandering through the dark void, right? Let the future deal with it.

I don’t know about anyone else, but that phrase along with other like “It’s not my job” and “I was only following orders” rile me up at their attempt to peer pressure those with independent minds into conformity. This is why revolutions happen and will continue to happen so long as there are humans with independent minds who don’t just “suck it up”.

The same will happen on a Worldship whether the nonbiology and nonpsychology and nonsociology majors engineers who designed it like it or not. Except this time they won’t be able to hop in a boat or plane and start a new life elsewhere. That won’t stop them from still revolting, with potentially dire consequences for all.

And what about those running the Worldship, assuming it is humans doing this and not some kind of AI? What will stop them from becoming tyrannical dictators, especially as they will be lightyears and centuries from any real authority on Earth? Many human factors that are not taken into consideration or glossed over I have noticed.

As I have said before and will repeat again, I do not think a Worldship is a good idea for interstellar voyaging unless there is no alternative and humanity is in some kind of imminent danger in the Sol system. And even then that does not mean it will be salvation. Maybe just a new form of oppressive dystopia.

I would love to be given reasons for being more positive about this, truly. Sadly I am a student of human history and all I can say at this point is I am amazed we put astronauts on the Moon at all and that we have not been knocked back into the Stone Age by a nuclear or biological war. Yet.

@ljk – the life of a dictator can be very uncertain. Look at the number of Caesars that were assassinated. You reach for that brass ring, but you could end up as fertilizer in an uprising. Perhaps staying in power results in expressing extreme brutality to keep the population in fear, with an armed power to maintain the status quo. While we may revolt in this idea, it isn’t as though people around our planet are not living under very similar conditions, with no “rescue” in sight and no way to escape. Does N. Korea not apply here as a topical example?

While I think the ideals of democratically run O’Neill-like worldship are attractive in books, reality will always be much more varied. Chancers are always looking for that edge to rise up the social hierarchy and in some cases to take control. We have seen it in the history of the US, especially in the first few centuries. We see it today (to a lesser extent so far), but I don’t see mass emigration. Why should we expect anything different on a worldship, or even a colony on a target world. To specifically answer your complaint, why should possible social “pathologies” stop human emigration?

No, what I’m saying is, they might or might not like it, but they certainly wouldn’t go mad from it. Plenty of things manage to be objectionable without destroying people’s minds. The human mind isn’t that fragile.

People will colonize space. Colonies will get further and further out. The return of travel times measured in months or years, instead of hours, will cause societal evolution at the fringe of colonization. And when one or another colony lights up a fusion rocket on their Kuiper object, and heads off into interstellar space, it won’t seem such a big leap to the people living there, even if the folks back on Earth would be terrified at the thought of their internet latency being several years instead of a second or two.

Alex Tolley –

Again, I am hearing “Well life might be tough for these wannabe colonists, even brutal, but that’s the way it may have to be in order to spread across the galaxy. They’ll get used to it.”

I bet if we could ask the population of North Korea to honestly answer how they feel living in that country, I think I can safely presume that unless they are in the power structure they are on the unhappy side and would either want a real democracy or leave quickly and permanently.

Brett Bellmore –

I did not say the Worldship folks would go mad – but they may become mad as hell and not take it any more. Yes, humans may be able to endure and adapt, but on Spaceship Earth you can still go far enough away from problems to escape them – though even that is beginning to change thanks to the Internet and faster methods of travel. On a very confined place like a Worldship, you don’t need to go or be crazy for serious problems to arise if enough people are unhappy with the situation.

Humans left unmodified will always act like they have for many thousands of years, which is to say largely tribal. I think we have taken on the trappings of civilization such as the technology and organization before we were truly ready biologically. I personally would not like to return to nature as it were and go on an eternal camping trip, but we shall see if all 7 billion of us can make it as a civilized society.

I suspect there is a misunderstanding here of what introversion and extroversion is. This is, by far, the most stable personality trait and it wouldn’t be if it was just about liking people. Take me, an extreme introvert, who on some tests (mis)measures as near the middle of the scale. I like people and parties, but put me in a large group and I have difficulty staying awake. Extroverts find the opposite. This is what marks the trait and it is set very deep.

Thus selection for introversion in such small groups as those on interstellar voyages seems a great idea with little downside IMHO.

@ljk – for most people. life is just about “suck it up”. How much is relative. N. Korea, Sudan, etc. really bad. Being a minority in the USA – not good. Don’t like it any more in the “land of the free” – where exactly are you going to go?

Space colonies and worldships will be no different, and size and architecture will impact the opportunity “change personal conditions or leave”. We should abandon the idea that they represent some sort of “heaven” as depicted in “The High Frontier” or “Elysium”. One person’s heaven is another’s hell. The only real issue is feasibility – what will work both technically and socially. And it may be that socially, the best solutions are isolation via cryo preservation, virtual reality, or similar. My guess is that if worldships happen, they will have people and social systems well adapted to life in isolated space colonies. That life might look quite grim to our sensibilities, but we won’t be invited along!

@Alex Tolley June 7, 2014 at 9:39

‘for most people. life is just about “suck it up”. How much is relative. N. Korea, Sudan, etc. really bad. Being a minority in the USA – not good. Don’t like it any more in the “land of the free” – where exactly are you going to go?’

Been a minority is relative, go into some parts of London and major cities in the UK and whites are the minority. There will always be people who are different, language, culture, colour and religion for example. Now even if you look at the worst affected groups their standard of living and medical access for example is even greater than that of the Kings of yesteryears, it is relative.

We have a natural tendency to see and compare ourselves to what others have even though down through the ages we have never had it so good.

Now even if it takes thousand years to get to another star system been in space has advantages, very large colony spaces can be built.

http://motherboard.vice.com/read/our-best-bet-for-colonizing-space-may-be-printing-humans-on-other-planets

The chief challenges are local resource exploitation, nurture and pedagogy. But with those issues solved satisfactorily, it does away with the need for “world ships” – slow, expensive and socially problematic – and also allows us much faster trip times due to the vastly reduced mass.

Rather than “printing adult humans”, better would be normal embryonic development. Otherwise, we are going to have a much longer wait for the tech to arrive.

My priority list for space projects is

1. A beamer mesh throughout our system

2. A set of gravscopes to identify the nearest viable interstellar system

3. A robotically-constructed starway (beamer based, per Quarra and Landis) to get us there

@Andrew – I would like some way to test the gravity focus telescopes concept first before we commit to that path. Getting to the focal point will take a long time, even with the best propulsion system we have (it needs to reach ~ 150+ AU – 3-5x further out than Pluto). If the sun isn’t as gravitationally “smooth” as we think, the image would be “blurred”, as would potential perturbing effects from other bodies. To observe a target, the telescope will need to move to track any relative motion of the system. Observing different targets will be constrained by how far the telescope will have to move. So while the basic idea is sound, we may be committing a lot of resources and time to a project that could fail due to uncontrollable features of the system.

I think it is time for a radical change for the human race. If it cannot become a better species, then perhaps it does not deserve to move on from its nest. How’s that for “sucking it up”?

@ljk – that would require some more powerful entity to administer. No evidence of any action on that so far in human history outside of religious tracts. So far there is no evidence of Clarke’s monolith builders deciding to “weed” us.

I think that judgements about human nature have nothing to do with our exploration/exploitation of space. To move substantially move forward in space, activities will need to be profitable to sustain them, otherwise they will always be dependent on the rest of the economy to support them, which will be impossible if there is to be a solar system wide economy and off-earth colonization.

Alex, I was invoking neither an alien nor supernatural method of changing humanity. I was thinking more along the lines of biotechnology, made by us.

I also think we may just be the “midwives” of a truly superior intelligence, but that seems to bother most humans for obvious reasons, thus all those anti-Artilect science fiction films and novels.

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2012/08/30/consciousness-christof-koch/

Assuming humans remain essentially the same as we have for a while now and yet somehow do manage to get into space permanently, I agree with you that it will probably happen due to blatant capitalism, even for the Chinese and Russians. After all, most exploration has been due to either money or military motives or both, why would it be any different with space? Our space programs exist because of geopolitical motives, literally riding atop rockets originally designed to carry bombs for blowing enemy targets to bits.

Perhaps once our descendants are living in space, seeing the stars on a regular basis and grasping the fact that there is more than just one world called Earth, they will evolve into if not immediately a better species then at least one which appreciates the value of a higher life beyond the meager ones far too many of us live with every day, ironically because we don’t have to worry about such things as if you shoot at each other in a pressurized enclosure, the possibility of puncturing a wall or window could be fatal to everyone present.

@ ljk – remember “Outland”? Gritty, no appreciation for being on Io, and thugs who did shoot inside pressure domes!

But I do take your point about evolved/enhanced humans. It could go in a number of directions, but one hope I have is that technology enhancement will improve our rational thinking which might lead to a better civilization able to cope more effectively with ignorance.

But most importantly, greater wealth from a solar system scale economy will raise more of us out of struggling for existence and improve the human condition. We may not become angels, but we might be able to improve a step or two.

I am sure there will be human stupidity in space. However, unlike on Earth, it does not take much to have it come to an abrupt end. One just has to hope it is contained and not harmful to the rest of the colony. It will also help thin the herd and be an object lesson to the others.

Space will teach cooperation and altruism. Humans out there will have to learn this or else. Until they can terraform another planet, then all bets are off.

I’m sure there will be no shortage of Darwin Award recipients. :)

Space will teach cooperation and altruism.

That is an interesting thesis. I haven’t seen anyone else exploring this. Are there Terrestrial analogs- e.g. sea going ships that might shed light on this?

I do not know, not having investigated it at the moment, but that does sound very interesting. I will say, though, that on a ship at sea of the wet kind, in most cases one can still hop in a lifeboat and row for an island. The Mutiny on the Bounty with Captain Bligh is a case in point.

In space, maybe you can hop in a lifeboat of the spaceship kind, but the “islands” will be much farther away on average and you will need to do more than just let the waves push you ashore into the sand. Plus if the power fails you on a nautical ship on Earth, at the least you do not have to worry about no longer having air to breathe or freezing to death in most cases.

Again, those in space will have to cooperate and play nice aboard the confines of a ship or small colony. Or nature will teach them a very rapid lesson with no second chance. Should we terraform or genetically develop humans who can actually live in raw space with no suits or ships or pressure domes, then we will see what lessons have been learned.

Why Extroverts Could Cause Problems on a Mission to Mars

By Rachael Rettner, Senior Writer | June 12, 2014 02:52pm ET

As NASA focuses considerable effort on a mission to send humans to Mars in the coming decades, psychology researchers are looking at what types of personalities would work the best together on such a long trip.

Now, a new study finds that on long-term space missions — such as missions to Mars, which could take as long as three years to complete a round trip — having an extrovert on board could have several disadvantages.

For example, extroverts tend to be talkative, but their gregarious nature may make them seem intrusive or demanding of attention in confined and isolated environments over the long term, the researchers say.

Full article here:

http://www.livescience.com/46295-extroverts-long-term-space-missions.html

No reason given. Just because. Perhaps another example of the bias against introverts. Just like women once couldn’t be astronauts in Nasa. Just because.