A new study of data from the Cassini Saturn orbiter has turned up useful information about, of all places, Europa. Cassini’s 2001 flyby of Jupiter en route to Saturn produced the Europa data that were recently analyzed by members of the probe’s ultraviolet imaging spectrograph (UVIS) team. We learn something striking: Most of the plasma around Europa is not coming from internal activity being vented through geysers, but from volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io. Europa actually contributes 40 times less oxygen to its surrounding environment than previously thought.

These findings cast one Europa mission possibility in a new light. In 2013, researchers using the Hubble Space Telescope reported signs of plume activity, which immediately called the example of Enceladus to mind. If Europa were venting materials from an internal ocean, a possible mission scenario would be to fly a probe through the plume, just as the Cassini team has done with its probe at Enceladus. The latter also has strong signs of an internal ocean, but its geysers are far more substantial than what Hubble has observed at Europa. The new Cassini data indicate that at least in 2001, the UVIS instrument could detect no plume activity on Europa.

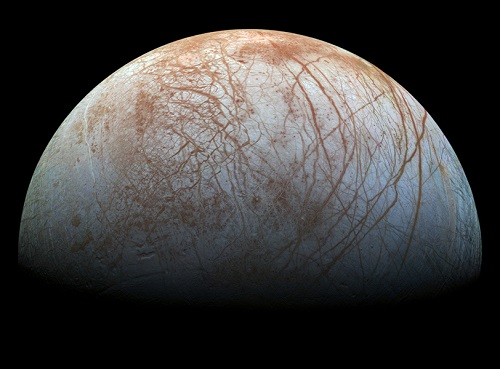

Image: Europa is a high value target in any case, but plumes would offer useful options for future spacecraft to study. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute.

In the mix here is the kind of plasma observed in Europa’s orbit. The UVIS instrument saw hot plasma there, a stark contrast to the cold, dense gas that marks out the orbit of Enceladus. The Enceladan plumes account for this gas, which slows down electrons being dragged through it by Saturn’s magnetic field, lowering the temperature of the plasma. If something similar is happening at Europa, there is little sign of it. Cassini could find no evidence that large amounts of water vapor were being injected into Europa’s orbit, so any Europan plume activity is minimal. Amanda Hendrix (Planetary Science Institute) is a Cassini UVIS team member who co-authored the new study:

“It is certainly still possible that plume activity occurs, but that it is infrequent or the plumes are smaller than we see at Enceladus. If eruptive activity was occurring at the time of Cassini’s flyby, it was at a level too low to be detectable by UVIS.”

Even the tenuous atmosphere around Europa, millions of times thinner than Earth’s atmosphere, turns out to be about 100 times less dense than previously believed, according to these results. So the Hubble findings point to the need for further study, to determine whether there is intermittent plume activity or not. Maybe what had been thought to be 200-kilometer high jets of water are an extreme rarity, or perhaps they were the result of a mistaken original analysis.

This story isn’t over, because New Scientist is reporting that scientists who discovered the original Europa plume are working on an rebuttal of the Cassini findings. The magazine quotes Kurt Retherford (Southwest Research Institute), one of the plume discoverers, as saying that Cassini was simply too far from Jupiter to get an adequate reading of Europa’s plume activity, adding “We would say using their technique, they couldn’t possibly find water.”

A future mission may be what it takes to make sense of observations that were at the outside of Hubble’s envelope and may not be repeated until we can get a closer look. If Europa isn’t venting water into space, its status as a highly interesting astrobiology target is hardly compromised, but a flyby through a plume will disappear from our list of mission possibilities. Can Hubble make a repeat, definitive observation to settle this?

The Cassini findings were presented on December 18 at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco. The paper is Shemansky et al., “A New Understanding of the Europa Atmosphere and Limits on Geophysical Activity,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 797, No. 2 (2014), p. 80 ff. (abstract).

Plume research on Europa is cool, but I am hoping they will send an ice melter there to have a look under the ice.

Any one have any concrete or “in the latest know” about any considerations for such a probe? Please let me know. I’d love to see what is underneath the ice in any oceans below. Tube worms, fish, perhaps even intelligent sentient sea creatures with intellects on par with or superior to Dolphins, Orcas and the like?

Well, from a a mission planning point of view, I really hope that the Europa’s plumes prove to be real and vigorous enough to carry subsurface material high above the surface of this moon (as happens with Enceladus). As I have written about in the past, such plumes would be a ready means of providing samples that could be inexpensively captured by a passing spacecraft and returned to Earth for detailed study. This sort of mission could be executed using today’s technology and for much less than a billion dollars (otherwise, we’ll have to wait decades and spend billions of dollars or more for a more complex lander-based system).

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2014/03/27/a-europa-io-sample-return-mission/

Why can’t we just clone the Mars Curiosity rover & Skycrane landing system, tweak the landing rockets for Europa gravity, refit it with a Europa-appropriate science payload including an ice melter probe and just get there and get it done?

“…or perhaps they were the result of a mistaken original analysis.”

I was concerned at the time that NASA announced that it “found” water fountains erupting from Jupiter’s moon Europa one week after it complained that the US Congress wasn’t giving it enough money to continue their Europa space probe mission.

http://www.spacepolicyonline.com/news/are-the-days-of-nasas-science-flagship-missions-over

Hmm … “plumes” from 12 politicised 2012 pixels?

http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/europa/docs/hstuvauroras_full.jpg

I really wish ESA or NASA would bite the bullet and do a Europa mission that can penetrate the crust and detect organics in the ocean below. All this pussy-footing around with orbiters isn’t really answering the important questions.

Does anyone know what are some concepts for Enceladus mission and if there is any chance of a mission happening within near future(by near I mean 20 years)?

I am also hoping that we see some further evidence of plumes and periodic subsurface liquid water on Ceres next year…

Video of American Geology Union annual conference session in Dec 2013 about Hubbel observation of Europa plumes.

http://youtu.be/ni61Ph1IayY

This lower oxygen in the atmosphere could actually bode well for oxygen in the ice. We know ions pelt Europa aplenty so where is the oxygen that should be released? It could be building up in the ice favouring transport into the sub ocean.

@Mark December 22, 2014 at 17:37

“Why can’t we just clone the Mars Curiosity rover & Skycrane landing system, tweak the landing rockets for Europa gravity, refit it with a Europa-appropriate science payload including an ice melter probe and just get there and get it done?”

ROFL!!!! If it were ONLY that easy. Europa is a totally different environment than Curiosity was designed for. It is much colder, totally airless and most of its instrument suite would be useless there. There is no sensible atmosphere so the aeroshell/parachute/skycrane combo used by Curiosity for descent would be useless and have to be totally redesigned for an all-rocket descent. And, despite what you seem to believe, the technology to melt through miles of ice with an automated system simply doesn’t exist. We are DECADES away from performing the mission you describe even IF sufficient funding were available (which it isn’t!).

@Andrew Palfreyman December 22, 2014 at 21:46

“I really wish ESA or NASA would bite the bullet and do a Europa mission that can penetrate the crust and detect organics in the ocean below.”

The technology to do what you propose does not exist and is DECADES away from implementation even if sufficient funding were available. You need to be setting your sights a lot lower for realistic missions to Europa that can be accomplished with the technology we have today (assuming the funding were even available… which it isn’t).

“Why can’t we just clone the Mars Curiosity rover & Skycrane landing system, tweak the landing rockets for Europa gravity, refit it with a Europa-appropriate science payload including an ice melter probe and just get there and get it done?’ Mark-that is an excellent idea! We have a basic design that works well; just tweak the landing capability for airless woulds, mass produce these rovers to drive the cost down …and deploy them all over the system; Mercury polar region, Ceres, the Galilean moons, Enceladus etc.

I am wondering if snow on Europa surface is having an effect of absorbing the ions and any oxygen released by its low density and large surface area. The temperature of the surface lowers the velocity of the oxygen particles quite a lot, not enough for escape so it is going somewhere, maybe into a matrix of pores and then into the ice below.

For all this cavlier talk about “melting through” or “penetrating” miles of ice, is there any even remotely feasible concept out there on how to do this? Actually?

Come on guys, think first.

A nuclear tipped probe would certainly have the energy available to melt or sublime its way through the ice. A problem would be controlling the waste ice or it will refreeze above the probe but then do we need to with having a long communication cable.

A 10cm diameter probe would only need to melt its way through say 100km of ice which is about 790 tons, which is only totalling 267035375555 J at 340kj/kg. U238 (560 W/kg) could do the job and we would need around 10 kg to melt through in a year or two, we would be aided by the pressure of the probe bearing down on the ice as well and carbon nanotubes have the advantage of reducing the melting point of ice in front of the probe if used. We could also choose a natural crack on the surface which firstly has depth to it and secondly has lower melting point ice in it all the way down.

This is napkin design by the way.

How about a giant foldable mirror in orbit around Europa to concentrate the Sun’s energy onto a spot on Europa’s icy crust not only to melt it but keep it melted until the probe can get through?

Can we use the Io plasma torus as an energy source? Two trillion watts of electricity flow between Jupiter and its volcanic moon.

http://www.planetaryexploration.net/jupiter/io/io_plasma_torus.html

Just laying on the table some grand scale ideas, I mean why not?

@ljk January 3, 2015 at 19:48

‘How about a giant foldable mirror in orbit around Europa to concentrate the Sun’s energy onto a spot on Europa’s icy crust not only to melt it but keep it melted until the probe can get through?’

It might be a real problem keeping it focused.

‘Can we use the Io plasma torus as an energy source? Two trillion watts of electricity flow between Jupiter and its volcanic moon.’

If we wrapped coils around the moons of Jupiter they would generate a lot of power as Jupiter’s powerful magnetic cuts them to melt the ice. We might be also able to set a smaller coil on the surface to power a lander and driller though. Both big engineering projects.

JUICE at Europa

Posted by Van Kane

2015/01/13 20:03 UTC

Topics: Jupiter’s moons, Europa, Ganymede, Future Mission Concepts, Callisto, Jupiter, JUICE

Late in 2030, Europe’s Jupiter Icy moon Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft will twice zoom past Europa, a world that has all the ingredients to harbor life.

During the minutes of each closest flyby, it will study areas identified from images taken in the 1990s by the Galileo spacecraft as locations of recent geological activity. Then after those two encounters, the spacecraft will move on to study Jupiter and the moons Ganymede and Callisto.

Unless another space agency commits to another mission that will visit Europa, this will be our only chance to explore Europa in the next several decades. (But see the note at the end of this post.)

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/van-kane/20150107-juice-at-europa.html