Speaking of spacecraft that do remarkable things, as we did yesterday in looking at the ingenious methods being used to lengthen the Messenger mission, I might also mention what is happening with Dawn. When the probe enters orbit around Ceres — now considered a ‘dwarf planet’ rather than an asteroid — in 2015, it will mark the first time the same spacecraft has ever orbited two targets in the Solar System. Dawn’s Vesta visit lasted for 14 months in 2011-2012.

We have the supple ion propulsion system of Dawn to thank for the dual nature of the mission. In the Dawn version of the technology, xenon gas is bombarded by an electron beam. The resulting xenon ions are accelerated through charged metal grids out of the thruster. JPL’s Marc Rayman, chief engineer and mission director for the mission, explained thruster design in one of the earliest of his Dawn Journal entries:

Because it is electrically charged, the xenon ion can feel the effect of an electrical field, which is simply a voltage. So the thruster applies more than 1000 volts to accelerate the xenon ions, expelling them at speeds as high as 40 kilometers/second… Each ion, tiny though it is, pushes back on the thruster as it leaves, and this reaction force is what propels the spacecraft. The ions are shot from the thruster at roughly 10 times the speed of the propellants expelled by rockets on typical spacecraft, and this is the source of ion propulsion’s extraordinary efficacy.

Slow but steady wins the race. For the same amount of propellant, a craft equipped with an ion propulsion system can achieve ten times the speed of a probe boosted by today’s conventional rocketry, says Rayman, but on the other hand, an ion-powered spacecraft can manage to carry far less propellant to accomplish the same job, which is how missions like Dawn can be executed. It’s also true that one of Dawn’s thrusters pushes on the spacecraft with about the force of a piece of paper pushing on a human hand on Earth. Dawn isn’t exactly the spacecraft equivalent of a Ferrari — at full power, the vehicle would go from 0 to 60 miles per hour in a stately four days.

Fortunately, space is a zero-g environment without friction, so the minuscule thrust has a chance to build up. ‘Acceleration with patience’ is Rayman’s term. In addition to enhancing maneuverability, ion thrusters are also durable. Dawn’s three thrusters have completed five years of accumulated thrust time, more than any other spacecraft. If all goes well at Ceres, we can’t rule out an extended mission that might include other asteroid targets, just as we hope for a Kuiper Belt object encounter for New Horizons after its 2015 flyby of Pluto/Charon.

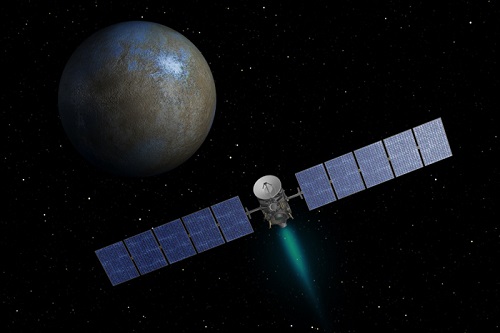

Image: An artist’s concept shows NASA’s Dawn spacecraft heading toward the dwarf planet Ceres. Dawn spent nearly 14 months orbiting Vesta, the second most massive object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, from 2011 to 2012. It is heading towards Ceres, the largest member of the asteroid belt. When Dawn arrives, it will be the first spacecraft to go into orbit around two destinations in our Solar System beyond Earth. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Keep an eye on Rayman’s Dawn Journal as the Ceres encounter approaches. His latest entry goes through the historical background on the dwarf planet’s discovery, and includes the fact that the Dawn team has been working with the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to formalize a plan for names on Ceres that builds upon the name given to it by its discoverer. Astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi found Ceres in 1801 and named it after the Roman goddess of agriculture. The plan going forward is for surface detail like craters to be named after gods and goddesses of agriculture and vegetation, drawing on worldwide sources of mythology.

Deep space has been yielding unexpected results since the earliest days of our exploration, and with Dawn approaching Ceres it’s instructive to recall some of the discoveries the Voyagers made as they moved into Jupiter space, starting with the surprisingly frequent volcanic activity on Io. Ceres will doubtless yield data just as intriguing, says Christopher Russell (UCLA), principal investigator for the Dawn mission:

“Ceres is almost a complete mystery to us. Ceres, unlike Vesta, has no meteorites linked to it to help reveal its secrets. All we can predict with confidence is that we will be surprised.”

Not quite twice as large as Vesta, Ceres (diameter 950 kilometers) is the largest object in the asteroid belt, and unlike Vesta, it apparently has a cooler interior, one that may even include an ocean beneath a crust of surface ice. We’ll know more soon, for Dawn has emerged from solar conjunction and is communicating with Earth controllers, who have programmed the maneuvers for the next stage of operations, which includes the Ceres approach phase. At present, the spacecraft is 640,000 kilometers from the dwarf world, approaching it at 725 kilometers per hour.

My take on Enceladus is that the heat is generated by a decoupled ice mantle and a rocky core grinding against each other as the tidal effects pull more on the ice mantle than the core during interactions with Saturn and the other moons creating a lot more friction than on a more ridged body.

Yes Michael that plays a very big role also. I love to think of it as the chewy v crunchy question as per NASA with this example

https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/articles/2001/6/22/europa-chewy-or-crunchy/

@Rob Henry

I was thinking along the lines of a very ridged frozen crust, softer mantle, ridged core and a slushy ice/clay interface between the mantle and core. The ice/mantle layer moves independently because a large torque is present (planet/moons) and the core has an inertia that prevents rapid movement, hence the grinding. Now I would have thought more heat would be present at the equator and not where we have the actual heat which is at the pole, the reason may be because the equator ice layer is much thicker by about 10 km.

Don’t despair Michael, there is a tidal mechanism by which we could preferentially heat the poles.

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v456/n7223/abs/nature07571.html

Note that this requires an axial tilt so small it is hard to measure. See how complex it gets!

I read in one of the links you put up Rob about Tidal Love Numbers. I think it somehow relates all this crunching, grinding and getting all heated does it not? Are those streaming watery plumes coming from Enceladus’ tiger stripes telling us something about Tidal Love, by chance?

Lionel, I am even more lost than you – more because I have been trying to model it longer. All I ever wanted is to know how much tidal energy was available for life beneath the ice in various moons and (hypothetical) exoplanets! Nevertheless here are my thoughts…

That very same reference says these figures are only known for our Moon. I note that Moon is unique in that we have a fossil record of both month length and day length

http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-67097-8_12#page-1

We are also unique in knowing where are moon first formed – just outside the Roche limit.

These, along with our detailed seismology-driven knowledge of the Earth, would help us model the long-term parameters of the Earth-Moon system. It is my current wild guess that those are needed to give accurate Love numbers – unless we witness a giant meteorite impact and record the seismic waves it produces. I further believe that if we use the current figure as that long-term for Enceladus, we don’t get sensible answers.

Are we there yet!