Back in September of 1961, Isaac Asimov penned an essay in Fantasy & Science Fiction under the title “Not As We Know It,” from which this startling passage:

…when we go out into space there may be more to meet us than we expect. I would look forward not only to our extra-terrestrial brothers who share life-as-we-know-it. I would hope also for an occasional cousin among the life-not-as-we-know-it possibilities.

In fact, I think we ought to prefer our cousins. Competition may be keen, even overkeen, with our brothers, for we may well grasp at one another’s planets; but there need only be friendship with our hot-world and cold-world cousins, for we dovetail neatly. Each stellar system might pleasantly support all the varieties, each on its own planet, and each planet useless to and undesired by any other variety.

Asimov’s idea, prompted by a monster movie excursion with his children, was to look at realistic ways that life much different from our own could emerge. Here he anticipated our discussions of habitable zones and just what they imply, for we usually speak of a world being habitable if liquid water can exist on its surface. Asimov would have none of that because he wanted to know what kind of life might emerge in the hottest and coldest places in the Solar System. Reprints of the essay inspired James Stevenson, a graduate student at Cornell University, whose recent work on the astrobiological possibilities on Titan has energized wide discussion.

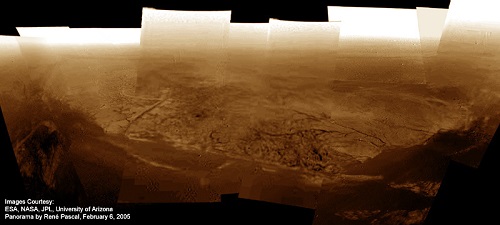

Image: Are there ways life could emerge on Titan? A panorama of the shoreline where Huygens touched down, stitched from DISR Side-Looking and Medium-Resolution Imager Raw Data. Image credit: ESA / NASA / JPL / University of Arizona / Rene Pascal (panorama).

Collaborating at Cornell with astronomer Jonathan Lunine and chemical engineer Paulette Clancy, Stevenson went to work on a cell membrane that could function in a cold and methane-rich environment. Clancy specializes in chemical molecular dynamics, while Lunine’s background includes working on the Cassini mission. With non-aqueous life on the table (Lunine had received a grant from the Templeton Foundation to study the possibilities), Clancy’s expertise seemed made to order. She comments on the work in this Cornell news release:

“We’re not biologists, and we’re not astronomers, but we had the right tools. Perhaps it helped, because we didn’t come in with any preconceptions about what should be in a membrane and what shouldn’t. We just worked with the compounds that we knew were there and asked, ‘If this was your palette, what can you make out of that?'”

It’s an interesting palette in a very interesting place. Liquid methane is the only liquid other than water that forms seas on the surface of a planetary body in the Solar System. The paper also notes the intriguing fact that there is an unknown process at work on Titan’s surface that consumes hydrogen, acetylene and ethane — these reach the surface out of the atmosphere but do not accumulate. Finding a cell membrane mechanism for Titan’s methane seas becomes an exercise in astrobiology that we can hope one day to weigh against data from the surface.

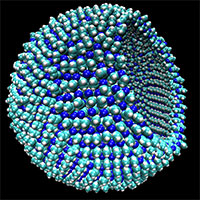

Using molecular simulation strategies given the challenges of cryogenic experimentation, the researchers screened for the best candidates for self assembly into membrane-like structures. The result: A cell membrane the researchers call an azotosome, made out of nitrogen, carbon and hydrogen molecules already known to exist in Titan’s frigid seas. If Earth life is built around the phospholipid bilayer membrane — water-based vesicles made from this are known as liposomes — then a methane-based membrane like the azotosome could be the Titanian analog, a flexible and stable cell membrane able to function at temperatures of -180 °C. From the paper:

In a cold world without oxygen, we suggest that the vesicles needed for compartmentalization, a key requirement for life, would be very different to those found on Earth. Rather than long-chain nonpolar molecules that form the prototypical terrestrial membrane in aqueous solution, we find membranes that form in liquid methane at cryogenic temperatures do so from the attraction between polar heads of short-chain molecules that are rich in nitrogen. We have termed such a membrane an azotosome. We find that the flexibility of such membranes is roughly the same as those of membranes formed in aqueous solutions. Despite the huge difference in temperatures between cryogenic azotosomes and room temperature terrestrial liposomes, which would make almost any molecular structure rigid, they exhibit surprisingly and excitingly similar responses to mechanical stress.

Image: A representation of a 9-nanometer azotosome, about the size of a virus, with a piece of the membrane cut away to show the hollow interior. Credit: James Stevenson.

Could such membranes form on Saturn’s largest moon? We already know that a liquid organic compound called acrylonitrile can be found in the atmosphere there, and the researchers believe that an acrylonitrile azotosome compound would offer indigenous life the same kind of stability and flexibility that phospholipid membranes bring to life on Earth. Studying the metabolism and reproduction of the hypothesized cells is the next order of business, but Lunine talks of one day going well beyond theory to float a probe on Titan’s seas to sample its organics directly.

None of this demonstrates that life is present on Titan, but focusing on the availability of molecules that can form cell membranes helps us understand the kind of chemistries we need to look for under cryogenic conditions. In their conclusion, the authors talk about the ‘liquid methane habitable zone,’ a wonderful reminder of how our views on astrobiology are expanding.

The paper is Stevenson, Lunine & Clancy, “Membrane alternatives in worlds without oxygen: Creation of an azotosome,” Science Advances Vol. 1, No. 1 (27 February 2015), e1400067 (full text).

What would the nuclaic material responsible for cell reproduction be composed of, and could cell reproduction proceed at a timescale anywhere near a human lifespan in such a poor energy environment?

That Nitrogen based Phospholipid analogue is what I have been waiting for

the astrobiologists to come up with. It does not even have to be correct in that Titan Life may use other alternatives. It just has to be possible.

What would be a nice follow up is a comparison of Energies derived from

the use of Acetylene to power any life here. On Earth we have C,H,O, compounds and/or Proteins as a power source (courtesy of plant kingdom photosynthesis) for most life forms. From scanning information on the NET, Acetylene seems very energetic on Earth, only because its burned with O2. So is Titan a place of reductive chemistry, which is what existed on earth prior to the arrival of the O2 in the atmosphere?. It is a lower order of energy extraction than oxydation. Could it support multi-cellular organisms, something like anemonies or even copepods analogues

Has anyone tried a Miller-Urey experiment using simulated Titanian conditions? While actually producing Titanian life forms is most unlikely, it might create a set of molecules that enhance the colors available on the “palette”.

Chris McKay and Heather Smith wrote an article in 2005:

” McKay, C P, & Smith, H D. (2005). Possibilities for methanogenic life in liquid methane on the surface of Titan. Icarus, 178(1), 274-276. ”

A few years later, Cassini detected a possible depletion of Hydrogen and Acetylene on the surface of Titan:

http://www.ciclops.org/news/making_sense.php?id=6431&js=1

http://www.nasa.gov/topics/solarsystem/features/titan20100603.html

Not a smoking gun for life, but certainly interesting. I think (hope) funding should flow away from dead Mars towards Europa, Titan and even Enceladus. They’re much harder to reach and explore, but the payoff should be greater.

Great lateral thinking. It’s hard to imagine true alien life because it’s so …well alien! This is starting that process off and is true astrobiology . Others have started envisioning alternate neural pathways. I was reading about the Ferni Paradox today and what it means . The various explanations as to its apparant fact …no alien contact , could be explained by many reasons but one that the article I was reading dismissed far too easily was the fact that being entirely different psychologically ( if that is the right word ) advanced aliens would simply ignore us .

On a slightly cynical note , membranes are one thing , but trying to drive any sort of chemical reaction at just 93K will take some doing ( ensymes?) so finding a suitable metabolic process to back up this clever science will be difficult . As a potential conflict of interest , Prof Lunine is heavily involved with both the Titam Mare Explorer and other such missions going forward . Good luck to him. With Titan and Enceladus still just “scratched” in terms of exploration there is a lot still to be done.

I wonder if Titan Mare could have helped to know either way.

All hypothetical of course, NASA opted for yet another Mars mission instead.

I suggest – with fairly little knowledge except that I can get from Google, that such membranes might hold a place similar to the lipid vesicles thought to have been the basis for protiocells on early Earth( see here: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2890201/). An experiment to see if such membranes really form, and if thety have similar properties to lipid vesicles, should be fairly do able. It’d at least give an experimental starting point… baring the next Titan lander!

I’m not as impressed by simulations of possible cell membranes as others commenting. Yes the molecules can create a membrane under Titan conditions. But would such a membrane form, and would its properties be useful to a possible Titanian cell?

A membrane might be able to contain a metabolism, but what mechanism and compounds would such a metabolism take? Then there is the issue of replication, required if the early cells are to evolve.

If Titanian aliens existed, what would they come up with for Earth life membranes using a similar approach?

This is useful knowledge even if abiogenesis and life are impossible under those conditions. By establishing the possibility of a metabolism within a body of some sort under those conditions it opens new paths for artificial autonomous entities. By this I mean something more sophisticated than a simple robot. In future we might build machines that can thrive in unlikely places and do exploration and other economically-valuable tasks for us. It could sustain itself (and even build other metabolism-based machines) as it proceeds.

IIRC, Chris McKay highlighted the potential role of ammonia on Titan (I haven’t read the linked article above so it may be in there although it may’ve been more recent).

This recent news about azatosomes is exciting. Looking further afield, maybe creatures such as Niven’s ‘Outsiders’ could’ve evolved somewhere too (although I’ll have to put Greg Benford’s take on their origin to one side, :(, sorry Greg)…

http://larryniven.wikia.com/wiki/Outsider

Titan’s was atmosphere created by gases escaping the core

4 hours ago by Elizabeth Howell, Astrobiology Magazine

Full article here:

http://phys.org/news/2015-03-titan-atmosphere-gases-core.html

Mark Zambelli: Right, Larry’s thinking over the Outsider origins question. But we wrote in the Ice Minds in BOWL OF HEAVEN & SHIPSTAR while thinking of the Outsiders, a story and connection yet to be explored–maybe in a forthcoming story for our next volume , collecting original Bowl stories…when we get around to it.

The Paper by E. Howell, has a nice clean logic, hopefully more data will continue to support it with more missions to Titan. Actually they mention a rover, but a Titan atmosphere skimming craft with the right equipment could do it. (it doesn’t need to be so expensive since it would be w/0 landing capability.

If this paper turns out to be proven as accurate, we might see the formation of Titan Atmosphere as pivotal as of the Oxygenation of the Earth? a different story obviously, but it sounds as if the Nitrogen-Methane atmosphere would have been there much much longer than the O2 accumulations on Earth.

If the CH4,NH3, N2 soup has been there for 4 billion or more

years I think the odds are flowing in the direction of finding life somewhere on Titan.

Gregory Benford… oooh, sounds good and I hope you do get the chance one day (I’d loved to have been a fly on the wall for those discussions).

I watched the SETI Institute’s latest talk last night about the lakes on Titan and the chemistry therein and it was perfectly timed to this article. I learned a lot about the suspected differences in concentrations of solutes between adjoining lakes, and more, so I’d recommend a viewing (and I like Barnes as a speaker)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAmhrb-JJlM

For those who want to read what the Good Doctor had to say on really alien biochemistries it was reprinted in the old “Cosmic Search” newsletter and is available online here: Not as We Know it – The Chemistry of Life

A more recent discussion of exotic biochemistry, which inspired Stephen Baxter’s recent depiction of Titanian life in his novel “Ultima”, is found in William Bains’ essay here: Many Chemistries Could Be Used

to Build Living Systems

In turn Bains’ work led to a collaboration with Sara Seager which provocatively argues for a hydrogen-based photosynthetic life: Photosynthesis in Hydrogen-Dominated Atmospheres [Open Accesss] …the full implications of which are yet to be explored. One irritating outcome is that such H2 based biospheres might be very hard to detect remotely.

With both Titan and Enceladus being one of the most intriguing objects in our Solar System, Saturn presents a very attractive target for any space exploration and astrobiology. I hope that we will get a mission there in near future that would arrive to study those both moons in detail in 20s. Their potential seems to be much higher than any other targets in our current exploration efforts.

Wojciech J: Surely Mars has better prospects–subsurface life implied by methane releases, ample surface water and atmosphere when young, and ease of getting to it. Especially when compared with the huge problems of subsurface oceans many km down. Plus no major chemical rocket expedition can be mustered. Exploring such moons demands a nuclear rocket capability we have done most of the development of, but many oppose out of nuclear fears, even in space. Etc.

This Nitrogen azotosome based life could be the default form of life in the universe, and Earth-type life the exception. Afterall, there are many bodies in our solar system that can host this kind of life whereas there is only one Earth here. The issue to deal with is that chemistry is slow in these kind of cryogenic environments. If this kind of life exists, it would be quite slow compared to Earth life, with very long evolutionary time scales. Thus, this kind of life would necessarily be simple, like our prokaryotes. I doubt it would have evolved anything as complex as our Eukaryotes.

“Wojciech J: Surely Mars has better prospects–subsurface life implied by methane releases, ample surface water and atmosphere when young, and ease of getting to it. Especially when compared with the huge problems of subsurface oceans many km down”

You could sample Enceladus by going through the plumes and collecting samples that would be scanned for traces of life. It is also worth nothing that in case of not all ice is that thick IIRC.

I am not against going to Mars, but its potential subsurface life probably would be simple based on what we can observe in subsurface life on Earth. Enceladus or Europa with ocean life offer more complex biological systems.

For subsurface life on Mars we will need manned mission, as I don’t think simple drilling probes will offer enough ability to perform a detailed search. Maybe some kind of distributed system of central lander plus drone swarm of climbers/collectors would work and be interesting innovative concept? We already have drones capable of such work.

In any case I am just a bit frustrated that such interesting system as Saturn and its moons doesn’t have any mission planned at the moment…Not to mention places like Triton sadly…Hopefully at least Saturn will get something started in next 10 years at least in terms of development.

NASA is doing conceptual research on sending a true submarine to Titan Kraken Mare to explore it sub surface ocean. It’s relatively new news form a relatively old news from June 2014. Just in February NASA had made a video to explain the tasks the submarine would have on Titan. Despite the sub being a 2 ton machine I can’t imagine how one could be landed on Kraken Mare.

Anyway.

1) Discovery News on Titan’s submarine with the video – http://news.discovery.com/space/alien-life-exoplanets/nasa-wants-to-send-a-submarine-to-titans-seas-150212.htm

2) Titan’s submarine paper – http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2015/pdf/1259.pdf

There are two significant ‘errors’I see in the comments above (or, rather, points that demand more discussion than given)

Robflores talks of the low energy storage, yet, on Earth, it is persistently oxygen diffusion rates not energy storage that provides bodyplan limits. On Titan hydrogen diffuses at more that twice the rate that O2 does on Earth, so these limits are not too different. Also, anhydrous acetylene (+H2) has a higher energy density on Titan than biologically hydrated glycogen (+O2) does on Earth.

Ashely Baldwin writes “trying to drive any sort of chemical reaction at just 93K will take some doing ( ensymes?) so finding a suitable metabolic process to back up this clever science will be difficult “, yet surely their is no choice. Most reactions here must involve free radicals for that very reason. The problem is, I can’t seem to find sufficient work on cryogenic organic free radicals to even give an educated as to how their kinetics would compare with typical Earth-biochemistry rates.

My Mistake R Henry;

I’ve recently became aware of the newer findings the early Earth atmosphere (after the Hadean, when the oceans formed) was NOT in fact very reductive at all. Does a more neutral early Earth Atmophere that make it easier for Single celled animals to experiment with different respiration paths, I would say yes.

Back to Titan’s chemical potential well:

Even if some of these compounds are a good source of energy,

there is still the question just how much is created by Titans natural processes

versus what limits it sets for total biological mass at least on the surface.

RobFlores writes “there is still the question just how much is created by Titans natural processes versus what limits it sets for total biological mass at least on the surface.”

And I am not feel it best to treat those two points separately.

We already have minimum measured values for those high energy chemicals, and H2 disappearing at the surface. They equate to 20W/sqkm energy, and I would guess it could even be as high as 200W/sqkm. Thus Titan’s subsurface ocean could provide 20,000 to 200,000 times as much energy as a purely geothermal driven Europa. If as active as Earth’s surface life that would be less than 1/10,000th its productivity, but there are two problems with this assessment.

1 Most of the biomass on Earth in probably endolithic which has a metabolic rate three or four orders of magnitude lower than surface life. Life on Titan may well have a similar pyramid.

2 Light levels at Titan are more than 1% Earth’s. Even taking account all their dust they are still around 0.5% of our insolation at its surface. If we cover that surface in photosynthetic life which has the efficiency of sugarcane, we would have a biosphere several percent (up to about 10% depending on how you do the calculation) as powerful as Earth’s.

The possibility of Captain Kirk wrestling mud monsters on its surface is not off the table just yet. More work needs to be done.

With Enceladus now thought to have warm ocean, Saturn system now looks more attractive than ever.I guess my main point was that while Mars is a dead world, both Titan and Enceladus are living worlds so to speak

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v519/n7542/full/nature14262.html

Above I probably have not put questions that are specific enough.

Carbenes can react to provide free radicals as both products and reactants. Does anyone know their stability at 93K.

Methylene (the simplest carbene) has a particularly high energy density – providing half an order of magnitude more energy by H2 reduction than carbohydrate under O2. Is that energy storage density not sufficient?