Andreas Hein recently wrote up the Project Dragonfly design competition, which has been running as a Kickstarter project. Leveraging advances in miniaturization and focusing on laser-beamed lightsail technologies, Project Dragonfly aims to study the smallest possible spacecraft. From the Kickstarter announcement:

Project Dragonfly builds upon the recent trend of miniaturization of space systems. Just a few decades ago, thousands of people were involved in developing the first satellite Sputnik. Today, a handful of university students are able to build a satellite with the same capability as Sputnik, which is much cheaper and weighs hundreds of times less than the first satellite. We simply think further. What could we do with the technologies in about 20-30 years from now? Would it be possible to build spacecraft that can go to the stars but are as small as today’s picosatellites or even smaller?

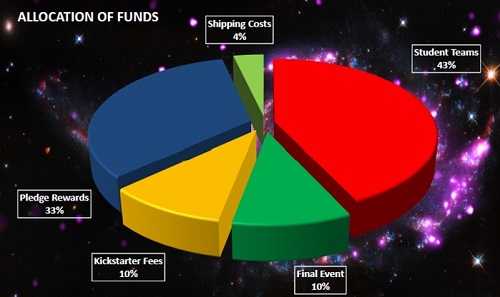

You can read about the competition in Andreas’ post Project Dragonfly: Design Competitions and Crowdfunding. He tells me that the Kickstar campaign has been fully funded since last Friday. But those interested in supporting the effort further can still do so for another three days. You can access the campaign at https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1465787600/project-dragonfly-sail-to-the-stars.

Not only can you go smaller, but also maybe lighter:

http://nextbigfuture.com/2015/02/nanolattices-have-potential-to-increase.html

Imagine a rocket for lifting 100 tons to space. If such materials could be used to construct the payload, reducing weight to say 10 tons, then you could use a much smaller rockets, hence less fuel. But if the rocket were mainly composed of the same sort of material then the dry weight of the rocket is also drastically reduced – once again meaning less fuel is required. And of course needing less fuel also means less fuel to lift the fuel. A feedback loop that is the reverse of the rocket equation.

But if the material is so light, maybe we can skip lifting the fuel altogether. Imagine a parachute shaped vehicle light enough to be lifted by microwaves. A ground-based station could be used to propel the vehicle, and its payload, until it’s just short of escape velocity. The payload could be released, and be carried by small rocket the rest of the way, while the larger vehicle falls back to Earth. Being so light, with such a large surface area, I wonder if it might not even be able to just glide down without harm. In effect, it would be a reusable vehicle that would only need a ground-based power plant to get it to orbit.

In the Space Coach post a while back, I imagine all those solar panels, even if thin film, would weight quite a bit. Imagine if the structure for those panels were 1/1000,000 the mass of what we have today, with just the active ingredients needed to produce energy being regular massed. It would allow such vehicle to achieve a greater speed. Just as it would probes of any sort whose structure is mainly composed of such material.

In a late 1970s issue of “Popular Mechanics” magazine (perhaps other readers here would know which one?), I once saw a brief article about a very similar proposal. The device was a passive, microwave-levitated relay reflector (‘a poor man’s Echo passive communications satellite,’ so to speak) shaped like an umbrella, which would be lifted to an altitude of 60 miles or so and held there by the microwave beam from an ordinary high-power microwave dish. If memory serves, it was intended for emergency use, and it would have been made of very fine wires, not unlike the late Dr. Robert L. Forward’s proposed “Starwisp” microwave-propelled interstellar probe.