Having written yesterday about the constellation of missions now returning data from deep space, I found Geoffrey Landis’ essay “Spaceflight and Science Fiction” timely. The essay is freely available in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Astrosociology, the publication of the Astrosociology Research Institute (downloadable here). And while it covers some familiar ground — Jules Verne’s moon cannon, Frau im Monde, etc. — it also highlights Landis’ insights into the relationship between the space program and the genre that helped inspire it.

My friend Al Jackson has written in various comments here (and in a number of back-channel emails) about Wernher von Braun’s ideas and their relation to science fiction. As Landis notes, von Braun was himself a science fiction reader who credited an 1897 novel called Auf Zwei Planeten (Two Planets) by Kurd Lasswitz with inspiring his interest in rocketry. So, by the way, did Walter Hohmann, the German engineer who helped develop the area of orbital dynamics and demonstrated fuel-efficient ways to move between two orbits.

Although there have been numerous editions of the Lasswitz book since its original publication, it would not be until 1971 that an English translation (badly abridged) was published. The story depicts the discovery of a Martian base at the Earth’s north pole, with humans being taken back to Mars for a look at its canals. Lasswitz followed Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell in his fascination with a thriving, fertile Mars and the ancient race that lived there. The science fiction historian Everett F. Bleiler believes Lasswitz was a major influence on Hugo Gernsback and hence on the shape of science fiction in the 1920s and ’30s.

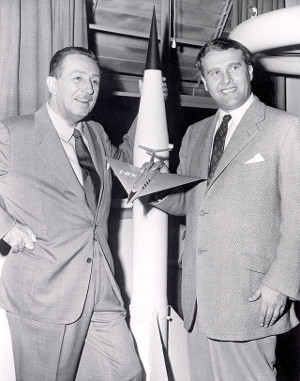

Image: Wernher von Braun with Walt Disney, with whom he collaborated on a series of three films. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

But back to von Braun, who lived in a Germany in which Fritz Lang made the 1929 film Frau im Mond (‘Woman in the Moon’) with the help of rocket scientists Hermann Oberth and Willy Ley, who were hired to build a real rocket to launch in synch with the film’s opening. That stunt didn’t happen, but Oberth, Ley and von Braun would have worked together in the early 1930s as part of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt, a rocket club created by amateurs that would go on to influence the development of the deadly V-2.

In his early years in the United States, von Braun wrote a short science fiction novel in German about a trip to Mars, one that describes intelligent Martians in the context of a carefully designed mission. This is where things get tricky for the bibliographer. The technical appendix for this novel was published as Das Marsproject in 1952, appearing as The Mars Project the following year. The novel that had included it was not published until a 2006 edition from a Canadian publisher, who offered it as something of a historical curiosity (available as Project Mars: A Technical Tale, from Collector’s Guide Publishing).

Science fiction, meanwhile, had entered a robust post-war era in which spaceflight seized the public imagination. Landis comments:

The V-2 brought the reality of rockets public in a highly visible way; rockets were no longer comic-strip stuff, but real and highly-visible tools of warfare and, presumably, spaceflight. Following the end of the war, the rockets on science fiction magazine and covers now all looked remarkably like the V-2, and science fiction entered a golden age, with spaceflight stories written by a number of classic writers such as Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke (who was also noted for inventing the concept of a geosynchronous communications satellite), Isaac Asimov, and Andre Norton reaching new audiences.

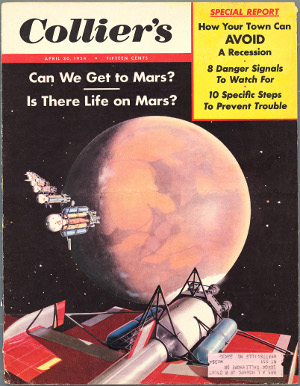

It was in this same era that Collier’s ran its highly popular series of articles on von Braun’s ideas, with eight issues illustrated by Chesley Bonestell and other artists between 1952 and 1954. Soon von Braun was a household name thanks not only to Collier’s but also Walt Disney’s TV programs, on which he appeared three times. By 1956, von Braun had scaled down his Mars mission and published his later thinking in The Exploration of Mars, written with co-author Willy Ley.

What effect did the space program von Braun did so much to launch have on the science fiction of its day? It’s an interesting question, and one that Landis is ambivalent about, for as we began to probe the planets, we learned that they differed sharply from what writers had imagined:

In some respects the space program was a disappointment to science fiction. Spaceflight has not become as simple and ubiquitous (nor as cheap) as science fiction predicted. The cratered Mars revealed by the Mariner and Viking missions was not nearly as colorful a setting for science fiction as the Mars of Percival Lowell, with its canals and ancient, dying civilization; the furnace of the Venus surface revealed by Russian and American probes was not nearly as picturesque a setting for science fiction as the earlier swampy or even ocean-covered Venus hypothesized by astronomers when all that could be seen were clouds. Even the moon, dry and grey and mostly lacking in resources, was a disappointment.

Image: The April 30, 1954 issue of Collier’s, part of a series that explored von Braun’s ideas.

What grows out of this is a turn in the field’s direction. If the Solar System was the great venue of exploration for the science fiction of the Gernsback and later Campbell eras, by the mid-1960s many of its destinations had been revealed as barren places (think Mariner 4 and its images of a cratered, evidently lifeless Mars). Interstellar destinations, Landis notes, became the new terra incognita, but so did an entirely different kind of exploration into social and psychological realms (Bradbury becomes an interesting bridge between these two worlds). Landis doesn’t say it but I assume he’s thinking that trends like science fiction’s ‘New Wave’ grew directly out of this impulse.

Think back, then, to some of science fiction’s precursors. Johannes Kepler could write in his Somnium (1609) about space travel by non-technological means in a book that used the Moon as a place where basic ideas of astronomy could be discussed. Edgar Allen Poe would develop his 1835 story “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” with a lunar trip using actual technology, in his case a balloon, finding ways to make Earth’s atmosphere extend high enough for a balloon filled with a new kind of gas to get there.

From Voltaire (Micromegas, 1752) to Verne, science fiction shaped spaceflight around technologies available at the time, like Verne’s 274-meter cannon driven by 200 tons of gun cotton. What could be envisioned drove the narrative, but so did the desire for an exotic destination on which humans could walk. It’s interesting that we’re again seeing Solar System destinations as revealed by the space program as settings for modern SF — I think of tales like Gerald Nordley’s “Into the Miranda Rift” as a classic in this vein — but the interstellar impulse has never been stronger as SF continues its quest for alien, habitable worlds.

A great post…

You are an encyclopedia of science fiction…

As on display in your book published by Copernicus…

Did von Braun’s team invent the inflatable space station?

Thank you! But I’ll never be considered an expert while there are guys like Bud Webster in the house:

http://www.amazon.com/Past-Masters-Other-Bookish-Natterings/dp/0615842828/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1433443763&sr=1-1&keywords=bud+webster

AIAA Houston reprinted the Collier’s Man Will Conquer Space Soon! series in their PDF newsletter (over several issues). Worth reading:

http://www.aiaahouston.org/tag/man-will-conquer-space-soon/

“In some respects the space program was a disappointment to science fiction. Spaceflight has not become as simple and ubiquitous (nor as cheap) as science fiction predicted. The cratered Mars revealed by the Mariner and Viking missions was not nearly as colorful a setting for science fiction as the Mars of Percival Lowell, with its canals and ancient, dying civilization; the furnace of the Venus surface revealed by Russian and American probes was not nearly as picturesque a setting for science fiction as the earlier swampy or even ocean-covered Venus hypothesized by astronomers when all that could be seen were clouds. Even the moon, dry and grey and mostly lacking in resources, was a disappointment.

What grows out of this is a turn in the field’s direction. If the Solar System was the great venue of exploration for the science fiction of the Gernsback and later Campbell eras, by the mid-1960s many of its destinations had been revealed as barren places (think Mariner 4 and its images of a cratered, evidently lifeless Mars).

Much science fiction of that early age was really a romance, with exotic, but recognizable locations. It also satisfied the western myth of exploring and taming those lands, whether the cowboy with little more than a horse and Winchester rifle, or the European explorer of darkest Africa, with his maps and pistol. Such locations were recognizable, with trees and macro fauna, with exotic twists. To me, that has always been somewhat boring. It is the truly exotic that is interesting, as well as the technology to explore it. Bradbury’s astronauts could live on Mars unaided, Clarke’s with oxygen breathers, but after Mariner astronauts needed spacesuits. Was the Martian landscape less interesting? Barren certainly, but hardly less so than Bryce canyon, or even the deserts of Lawrence of Arabia fame. The exposed rock formations and vistas revealed by our robots look as interesting as any on Barsoom. For the better SF writers, even the lack of breathable air can be overcome. Whether Varley with his body hugging force fields, Sawyer with his mind embodiment in android bodies, or Robinson and Jablokov with their tented and underground cities, Mars can be as much a livable place as the American West.

While I mourn the loss of the alternative history of Clarke’s Space Odyssey, my spirits are brightened by how much more our robots do. On the way to Iapetus, Bowman and Poole do almost no science, occupying their time with the mundane chores of monitoring the ship. Cassini, in contrast has mapped much of the Saturnian system, landed a probe on Titan and sent back a library full of information about all these worlds, even if no alien artifact was to be found. In many respects, Cassini has shown us much more interesting worlds than any imagined by the writers. And Kepler is hinting at such truly exotic worlds that beg to be explored by our post-human descendants, in whatever forms they take.

Well, if Von Braun hand a hand for the Voyage to Mars “ride” at

Disneyland Circa 60-70’s. I have to say that he helped invent one of the best ways to take a nap while the kids ramble around Tom Sawyer Island.

Or maybe he had nothing to do with it and needed his touch.

Modernizing Disneyland took away a cultural vernacular along with

obsolete rides…….the E ticket ride.

I remember 2nd hand stories about Von Braun from told by those he worked with. This one you may know. In the attempt to catch up with the soviets and land on the moon first. NASA wanted to test the Saturn S IC engine and S II all up test. This was the 1st two stages of the Saturn V rocket. Von Braun was Horrified at the risk, as he wanted full tests on the separate stages completed 1st.

At any rate kudos P.G on finding that photo of Disney and Von Braun and yes we would all like to know about what they talked behind closed doors.

About the Good Old Days ( = post Victory ) ?

I still find the vision of the Collier’s space program compelling, as it exemplifies a particular paradigm of spacefaring civilization — one that did not come about. If we pass through the filter of contemporary apathy and establish a spacefaring civilization at some time in the future, it will not look like the Collier’s space program, so that the latter remains a permanently unactualized possibility.

Everyone should read Voltaire’s great story “Micromegas”, as it is a good read and its ideas still apply to our current culture, which is both good and bad:

http://wondersmith.com/scifi/micro.htm

To quote from the story:

The conversation grew more and more interesting, and Micromegas spoke as follows:

“O intelligent atoms, in whom the Eternal Being has been pleased to manifest His skill and power, you must doubtless taste joys of perfect purity on your globe; for, being encumbered with so little matter, and seeming to be all spirit, you must pass your lives in love and meditation–the true life of spiritual beings. I have nowhere beheld genuine happiness, but here it is to be found, without a doubt.”

On hearing these words, all the philosophers shook their heads, and one, more frank than the others, candidly confessed that, with the exception of a small number held in mean estimation among them, all the rest of mankind were a multitude of fools, knaves, and miserable wretches.

“We have more matter than we need,” said he, “the cause of much evil, if evil proceeds from matter; and we have too much mind, if evil proceeds from mind. For instance, at this very moment there are 100,000 fools of our species who wear hats, slaying 100,000 fellow creatures who wear turbans, or being massacred by them, and over almost all of Earth such practices have been going on from time immemorial.”

The Sirian shuddered, and asked what could cause such horrible quarrels between those miserable little creatures.

“The dispute concerns a lump of clay,” said the philosopher, “no bigger than your heel. Not that a single one of those millions of men who get their throats cut has the slightest interest in this clod of earth. The only point in question is whether it shall belong to a certain man who is called Sultan, or another who, I know not why, is called Caesar. Neither has seen, or is ever likely to see, the little corner of ground which is the bone of contention; and hardly one of those animals, who are cutting each other’s throats has ever seen the animal for whom they fight so desperately.”

“Ah! wretched creatures!” exclaimed the Sirian with indignation; “Can anyone imagine such frantic ferocity! I should like to take two or three steps, and stamp upon the whole swarm of these ridiculous assassins.”

“No need,” answered the philosopher; “they are working hard enough to destroy themselves. I assure you, at the end of 10 years, not a hundredth part of those wretches will be left; even if they had never drawn the sword, famine, fatigue, or intemperance will sweep them almost all away. Besides, it is not they who deserve punishment, but rather those armchair barbarians, who from the privacy of their cabinets, and during the process of digestion, command the massacre of a million men, and afterward ordain a solemn thanksgiving to God.”

The traveler, moved with compassion for the tiny human race, among whom he found such astonishing contrasts, said to the gentlemen:

“Since you belong to the small number of wise men, and apparently do not kill anyone for money, tell me, pray, how you occupy yourselves.”

“We dissect flies,” said the same philosopher, “measure distances, calculate numbers, agree upon two or three points we understand, and dispute two or three thousand points of which we know nothing.”

Here is an article on the collaboration between Walt Disney and von Braun. The space programs of the 1950s were and still are incredible. They can be found on YouTube.

http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/disney_article.html