If you’re a long-time reader of this site, you doubtless share my fascination with the missions that are defining our summer — Dawn at Ceres, Rosetta at comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, and in the coming week particularly, New Horizons at Pluto. But have you ever wondered why the fascination is there? Because get beyond the sustaining network of space professionals and enthusiasts and it’s relatively routine to find the basic premise questioned. Human curiosity seems unquenchable but it’s often under assault.

‘Why spend millions on another space rock?’ was the most recent question I’ve received to this effect, but beyond the economics, there’s an underlying theme: Why leave one place to go to another, when soon enough you’ll just want to go to still another place even more distant? The impulse to explore runs throughout human history, but it’s shared at different levels of intensity within the population. I find that intriguing in itself and wonder how it plays out in past events. The impulse is often cited as a driving motif that has pushed human culture into every corner of the planet, but it comes in waves and can lie fallow until new discoveries bring it to the fore.

Back when I was writing Centauri Dreams (the book), I looked at the Conference on Interstellar Migration, which was held in 1983 at Los Alamos. This was a multidisciplinary gathering including biologists and humanists along with physicists and economists, and a key paper there was the synergistic work of Ben Finney (an anthropologist) and Eric M. Jones (an astrophysicist). Called “The Exploring Animal,” the paper argued that evolution has produced an exploratory urge driven by innate curiosity. The authors considered this the root of science itself.

It was probably the Los Alamos conference that introduced the theme of Polynesia into interstellar studies, the idea being to relate the settlement of the far-flung islands of the Pacific to future missions into the interstellar ocean. From Fiji, Tonga and Samoa and then, in another great wave, to the Marquesas, Hawaii and New Zealand, using double-hulled dugout canoes with outrigger floats, these explorers pushed out, navigating by ocean swells, the stars, and the flight of birds. Finney and Jones call this the outstanding achievement of the Stone Age.

Here’s an excerpt that puts the view succinctly:

The whole history of Hominidae has been one of expansion from an East African homeland over the globe and of developing technological means to spread into habitats for which we are not biologically adapted. Various peoples in successive epochs have taken the lead on this expansion, among them the Polynesians and their ancestors. During successive bursts lasting a few hundred years, punctuated by long pauses of a thousand or more years, these seafarers seem to have become intoxicated with the discovery of new lands, with using a voyaging technology they alone possessed to sail where no one had ever been before.

And to me, this resonates when you see something like this:

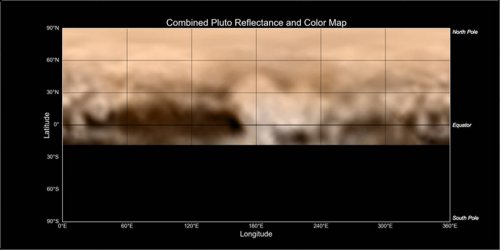

Image: This map of Pluto, made from images taken by the LORRI instrument aboard New Horizons, shows a wide array of bright and dark markings of varying sizes and shapes. Perhaps most intriguing is the fact that all of the darkest material on the surface lies along Pluto’s equator. The color version was created from lower-resolution color data from the spacecraft’s Ralph instrument. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Are Finney and Jones right that there is an ‘intoxication’ in the discovery of new lands? It’s certainly a sense I have, and most of the people I deal with in aerospace clearly have it. But note as well the fact that these bursts of expansion into the Pacific were also marked by long pauses, thousand-year breaks from the outward movement. We can see this as a process of consolidation, I suppose, or maybe a broader cultural fatigue with the demands of exploration. Are we entering a similar era in space, a time of reflection and retrenching before the next great push? If so, we have no good guidelines on how long that period may last.

In his new book Beyond: Our Future in Space (W.W. Norton, 2015), Chris Impey likewise speculates on the urge to explore. Humans do it differently from animals, after all — we are the only species that moves over large distances with a sense of purpose and organization, sometimes for reasons that have little to do with the availability of resources. Like Finney, Impey cites the Polynesian example, seeing it as driven by a mixture of culture and genetics.

Are there specific genes that come into play in at least parts of the population to make this happen? Because we all know that for some people, exploration is not an option — not even an interest. Most of Europe stayed home when the ships that would open up the Pacific and the Orient to western trade and expansion set sail, and remained at home while emigrants took to the seas to settle elsewhere. Even so, in every era, the exploratory impulse seems firmly planted, which is why even dangerous missions always find no lack of volunteers.

Impey is interested in certain developmental genes that he believes give us advantages over other hominids. In particular, he focuses on a gene called DRD4, which controls dopamine and thus has influence on human motivation and behavior. A variant of this gene known as 7R produces people more likely to take risks, seek new places and explore what is around them. About one person in five carries DRD4 in its 7R form. Impey notes that the 7R mutation occurred first about 40,000 years ago as humans began to spread across Asia and Europe.

Impey doesn’t go so far as to call this an ‘exploration gene,’ but he does think that carriers of 7R are more comfortable with change and are better problem solvers. From the book:

Even if they’re only present in a fraction of the population, the traits that favor adventurousness are self-reinforcing. If the 7R mutation has slightly higher frequency in a population that migrates, that frequency will increase in a finite gene pool. Mobility and dexterity are enhanced as they are expressed. The most successful nomads will encounter new sources of food and new possibilities for enhancing their lifestyle. The best users and makers of tools will be spurred to come up with new tools and novel applications of existing tools. The fulcrum of this feedback loop is our one attribute that’s unparalleled: a big brain.

Is DRD4 7R the source of the internal fire that drives our explorations? It’s a pleasing thought, for it implies that despite periods of pullback, the exploratory impulse is ever outward, for it exists as part of the template of our species. I doubt we can pin curiosity and migration down to this one salient, but our past does imply there is something within us that accounts for our restlessness. Whatever that something is, we find it reinforced in the great explorations of our time. And it seems to be strong enough to survive the periods of retrenchment and apathy that sometimes punctuate our efforts, and that tend to get lost in the big picture of history.

Yesterday’s post asked whether we were nearing the end of an era with the flyby of the last of the ‘classical’ planets. The answer is yes, but the beauty of eras ending is that they have successors, and our inherent human curiosity is not something that can be long suppressed. The Voyagers have already begun the bridge between the interplanetary era and the interstellar, and New Horizons will soon enough follow. Keep in mind the words of Andre Gide when New Horizons swings about to take images of Pluto and Charon receding in the night: “Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

A great post and a great quote…

Andre Gide: “Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

Bear in mind that the question, “Why another. . . ” is honestly asked. Agoraphobia is as powerful, perhaps more so, as the drive to explore. The Mountain Men of past ages found some avocation to help finance their wanderlust but they were not buffalo hunters and beaver trappers primarily. They were the malcontents and misfits in the civilized world of the time.

If elected leaders are more agoraphobics than adventurists, and I would think they, being empire builders of a sort, then major explorations will stop. When the Space-coaches are ready to travel, it will be the misfits that are most willing to go. And, like the Mountain Men, they will be willing to endure hardships and high risks without any promise of financial compensation: the journey is the objective.

Thinking about a pause in outward exploration…I think that next year marks a more significant “end of era” than the flyby of Pluto. The Space Age began with the launch of Sputnik, coincidentally during one of the windows of opportunity to launch a mission to Saturn using a Jupiter gravity assist. The suitable alignments of Saturn and Jupiter are infrequent…they come about once every 2 decades.

Obviously, when we were barely started launching our first satellites we weren’t going to send a mission to Saturn. But since the start of the Space Age, we have taken advantage of each Jupiter-Saturn alignment to send a mission to Saturn. The Voyagers were sent during our first chance. Cassini was sent during our second chance.

Next year marks our third chance. But this time, we’re not sending a mission to Saturn. There’s not enough time to prepare a mission to Saturn within this window.

If anything marks a pause in our exploration of the Solar System, this surely does. The Jupiter-Saturn alignments are infrequent enough that a Saturn mission should be prioritized over other missions…otherwise we could be looking at a FORTY YEAR GAP or more between Saturn missions. The fact that we have not done so demonstrates a failure of mankind.

In fact, one mission that’s still a near term possibility is an Enceladus plume sampling mission, but even if it happens it will be severely minimized in payload due to the lack of Jupiter assist. If we had our act together, an Enceladus sampling mission would already be under construction and scheduled for launch next year.

I hope our first failure to miss a Saturn mission window since the dawn of the Space Age is just a hiccup, but maybe it will turn out to be emblematic of a pause…

I am quite sceptical about this exploration thing. I don’t say it does not exists but it is not the main motivation for travellingand establishing in an other land.

Survival is the main motivation, because people are fleeing poverty, famine, war, persecution, insecurity and bullying. They do not really want to leave their country, but they have no choice.

I get the drive to explore, really. It’s a feeling of yearning for wonder and for discovering unknown that has awoken in many since childhood.

Maybe thanks to the persistent cultural admiration we have for brave explorers of all ages, their stories permeating in popular culture in the form of books, art and the loving tales narrated by the dear ones that helped us grow. Maybe as Carl Sagan, it’s a biological rooted ‘itch’ that makes us restless, even if we have tamed nature and we are living unnaturally plentiful lives that won’t require that drive for exploring unexplored lands.

Nevertheless, the sole drive for exploration is not enough. The reason for it is that, even if really big, the frontiers are still limited and finite.

If we consider the mere objective of exploring as the main reason for going to space, then we will reach a point where we have no reason to go anymore.

When all the bodies in the traditional Solar System have been visited by a probe and pictured, what’s left to do?

Space scientist could argue endlessly against this conformist view, but for the average citizen, the one that votes and says if space travel is relevant for them with that vote, anything more would be just more of the same.

In my belief, we need to emphasize switching towards a “what’s in it for me?” mentality about space. Yes, find the commercial and personal interest to go there, and less of the romanticized version of space, where space exploration is seen as an ethical goal, for all of humanity. Mostly, something to be paid by the taxpayer for the public good.

Because, you know, taxpayers aren’t very patient with endeavors that don’t bring anything new or anything good and tangible for them.

IMO change and growth necessarily passes through more mundane objectives and actions. Like building drones that could prospect, mine and transform resources in space, for usage in space or for shipping them to Earth.

Or like building rockets for having access to cheap launches and place Internet satellites in space ( a la Elon Musk), things like that.

It’s only through the invasion of space by people’s interests, desires and wants that we will make possible the dream of really exploring and getting to know space in personal terms.

Because most of great explores of the past weren’t in it for the glory and for the ethical advance of humanity either. They were there for the riches, for land-grabs and for theirs and their nation’s interests.

If we aren’t able to engage that part of our human nature (greed, desire) with things in space, then we won’t be going. After all Earth is perfect for sitting in it for a long time.

A very intriguing idea. I like that it acknowledges that some people are different and inherently so. My own belief is that you won’t make people excited for space colonization any more than you can use a rational argument to get someone to switch their favorite flavor of ice cream.

The problem we face is that a spaceship requires the dedicated effort and resources of many people. The adventurous can’t just hop in an outrigger and take the risk for themselves. On top of that, the scale of space is just so huge as to be incomprehensible. In terms of scale it doesn’t compare to crossing oceans or the advances of air flight, even if those metaphors seem appropriate to our terrestrial brains. Because of that, I think it’s incredibly hard to predict everything that needs to come into place for us to make that leap as a society.

My own guess is that the technology will change faster than the society. As the technology becomes cheaper, more effective and ubiquitous, it simply becomes accepted and assumed (like satellites already are). For that reason, I’m much more excited about crowdfunding cubesats, than getting a few privileged humans on another planet at an incredible expense. I’ve seen people lament about how boring the internet is compared to their visions of the future, but lo and behold, the humble internet is playing a key role. While folks in this community often talk about the spinoff technology of space travel, the influences of other technologies on space will probably be larger. Advances in computing, nanotechnology and robotics are changing our ideas of what is possible all of the time.

I guess what I’m saying is, we’re getting closer to the analog of the space “outrigger” or spacecoach if you will. Advances that help space travel are happening every day all around us and are well outside of the budget of space programs. When it is fast and cheap enough, I have no doubt that humanity will make the leap,

I think the “malcontent” may be closer to the mark than the “exploration” gene. It’s more than just geographic. It pushes all sorts of limits. It tends to be destructive for the individual, but as pointed out above has advantages for the gene pool.

Curiosity definitely plays a role in at least some of exploration, otherwise there wouldn’t be private and non-profit donations to scientific work. That said, that only seems to go so far – there’s a paucity of privately funded scientific space missions, for example.

I’m not sure how much cheaper that can get, either. You can build some compact robotic spacecraft, but you can’t necessarily shrink all of the instruments they need as well as the power supply and communication down a ton either if you want your robots to do some serious science.

@Craig Watkins

I agree. I think there is more than the gravity well keeping us on Earth for the time being. There is IMO an “entry barrier” for our culture to become spacefaring, made of things we have to overcome for allowing people (not just machines) to go there.

That entry barrier is made of the required science and technology that we must develop for making things work, economically, technically and socially. Some of these things we can see, others we can’t, but we’ll recognize them when they are overcome.

Hyper-expensive launchers are part of the entry barrier. Until they are overcome with cheap launchers, we will be doing only timid attempts into space.

Another barrier is the propulsion technology, barring long manned missions. Currently we can’t think of going beyond Mars in person. Gee, we haven’t even gone there. This needs to be overcome for allowing us to go without fear of radiation poisoning and other dangerous, debilitating conditions.

Another barrier is politics. We have powerful energy sources (nuclear energy) that could ease some of these problems, but we are too afraid to use them, therefore, we have banned them with our without reason. These kinds of barrier seems even harder to overcome, except if we actually invented safer, acceptable equivalents.

It is difficult to see the selective advantage of a “wanderlust gene” as the likelihood of reproduction must lessen. Those archetypical mountain men weren’t going to have offspring with the local bears and mountain lions!

While groups will wander to escape poor conditions, this doesn’t seem to account for individual wanderlust. I wonder if it is is something else, perhaps a desire to be away from your own tribe, perhaps any people, a sort of anti-social trait. Are we humans unique in this? I don’t know. I suspect not. Our unique advantage is being able to use technology to aid travel and protect ourselves from adverse elements.

But one thing I have noticed amongst the cohort I went to school with. Sort have scattered to all parts of the world, while many have stayed within a few miles of their birth and seem to have no interest in travel to, let alone living in, distant places. Whether this is genetic or cultural or some combination, I have no idea. The only clue I have is that the science educated (in the UK we split directions early and well before university) seem to have a greater desire to travel, and that may be due to curiosity, rather than wanderlust or a desire to “explore”.

That projection of Pluto, so blurry just demands closer inspection. I hope NH flies by in perfect health to show us a lot more fine detail.

From the July 8 image:

Is that a canal on the lower left of the “heart”? :)

Really enjoyed this post Paul. I love the thoughts about an exploratory gene, and the human urge to explore. Although there are some interesting species (birds and sea creatures who migrate vast distances) who also seem to share our exploratory urges. I’m curious whether some of these species carry a similar gene? Some really eloquent and inspired writing at the end that gave me the impression you were really moved by this line of thinking. Definitely bookmarking this post!

Sending probes to distant planets, fly-bys and long term projects with enormous cost are not classical exploration. It is more akin to intellectual curiosity and high tech gadgetry, and has an element of the ultimate video game. On this site and others of this type I have seen a lot of role playing. There is a lot of talk of “star-faring” civilizations, warp drives and other FTL technology, visiting the nearest star sometime in the next 50 years. You can’t sell that to someone with a mortgage and three kids nearing college age.

We have had presented a viable vehicle for honest exploration. The spacecoach concept is doable and has the potential for self- sustaining outposts. This is exploration in the most basic human terms and I believe it will engage the hearts and souls of the populace. As far as economic payout, that was not required New Horizon, so why must it be required for the first steps in establishing a lasting human presence in near space?

Frank Taylor writes:

One thing I know for sure is that you’ve got the gene, Frank. For those who don’t know, my friend Frank has just returned from a five year sail around the world, chronicled on his site:

http://www.tahinaexpedition.com/

The archives are stuffed with photography of some of the most exotic places on the planet. Talk about navigation through huge distances! Great to have you back, Frank.

Maybe Kon Tiki to the Stars expresses the notion better than Stagecoach? The involvement of entrepreneurial personalities, Musk, Branson, Cameron, etc. in spaceflight (consider Branson’s personal involvement in high altitude ballooning adventures and Cameron’s ocean deep explorations). Might we someday witness an individual with means strike out on their own?

Isaac Kuo wrote (in part):

“But since the start of the Space Age, we have taken advantage of each Jupiter-Saturn alignment to send a mission to Saturn. The Voyagers were sent during our first chance. Cassini was sent during our second chance.”

There was also a 1973 Jupiter-Saturn alignment (a rather circuitous one, but the transit time between those two planets was still only about five years [1974 – 1979]), which Pioneer 11 took advantage of. It also provided a data-rich passage above (north of) the Sun, out of the ecliptic, on the way to Saturn. Regarding humans’ urge to explore:

Even those people who stayed behind (the vast majority, in Europe) were entranced by travelers’ tales, and they bought books by travelers that chronicled their visits to distant and exotic lands (some were largely or entirely fictional, as fact-checking was on the honor system…). If the costs of missions aren’t noticeably burdensome (at a Pioneer 11 Saturn encounter press briefing which also included Voyager findings on Jupiter’s Galilean satellites, the presenting scientist remarked that Voyager was a “one six-pack of beer mission” and that Pioneer 11 was a “two cans of beer mission,” in terms of their cost per year to each U.S. taxpayer), I see no reason why planetary exploration can’t continue, although any currently-conceivable interstellar probe mission would have to have a long development schedule to avoid becoming noticeably expensive to support each year.

Paul, this is the kind of article that brings me back to CD on a regular basis. If we were to make a list of behavioral traits of any exterrestrial intelligence we might encounter, a compulsion to explore would probably be one such trait. It is hard to imagine how there would not be a natural selection bias favoring explorative members of an evolving primate-like intelligent species.

This is to Paul. If I recollect properly, the probe will fly by somewhere around seven or eight a.m. Eastern standard Time on July 14th. That’ll be as point of approximately closest approach to the planet Pluto. My question to you is, do you happen to know whether or not that point of closest approach just mentioned will be the time here on earth that the first close-up pictures arrive from Pluto. Or will this happen to be the time here on Earth when the probe is passing by closest to Pluto AND the pictures will actually ARRIVE here on Earth about four and a half hours later, putting it somewhere around the time of 11 a.m. or 12 p.m. Eastern standard Time ? Do you happen to know which interpretation is the correct one ?

The post today (Friday the 10th) answers this. Close approach happens at a time when we’ll not be communicating with New Horizons because it’s busy taking data. We should be seeing the first imagery on the afternoon of the 15th. Here’s the schedule:

http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-announces-updated-television-coverage-media-activities-for-pluto-flyby